The Wild True Story Of World War II's Third, Unused A-Bomb

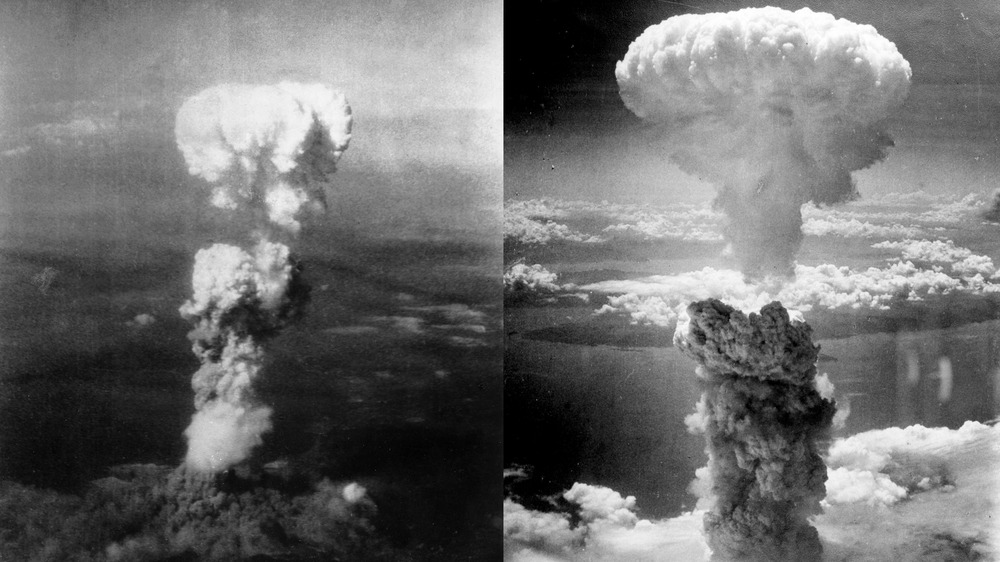

On August 6, 1945, the uranium-235 core of the bomb dubbed "Little Boy" was detonated 600 meters in the sky above Hiroshima, Japan. The blast vaporized everything within two kilometers of the hypocenter, obliterating 92 percent of the city's structures and killing about 140,000 people, as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum recounts. Three days later, on August 9, the plutonium-239 core of "Fat Man" was detonated 500 meters in the sky above Nagasaki, but a nearby mountain ridge contained the blast to the city's Urakami district. As the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum also tells us, 36 percent of the city was consumed, and about 74,000 people killed. (For those wishing to learn more about the true horror of those days, poet Yamaguchi Tsutomu, who survived both blasts, chronicles his ordeals in And the River Flowed as a Raft of Corpses.)

The terrifying events of those two days, and their fallout, effectively brought an end to World War II with Japan's surrender on August 15. They should have been enough to teach all those involved, and all subsequent generations, to put a lid on atomic weaponry. In some ways, humanity has. There's been no nuclear holocaust. The Cold War's Deterrence Policy was a kind of terrible success. And in the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the United States didn't drop its third bomb.

That bomb's "demon core" would have its revenge, though, on the scientists who toyed with it in the days following the war.

Tickling the sleeping dragon's tail

"[T]he bomb should be ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17 or 18 August," General Leslie R. Groves wrote to General George C. Marshall on August 10, as the blog Nuclear Secrecy shows. Instead, the "demon core" — a 14-pound, plutonium-239 sphere — made its way to Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico under the purview of physicists Harry Dahglian and Louis Slotin.

Until then, atomic bombs were, as The New Yorker describes, "handmade, artisanal product[s]." They didn't go off automatically. Rather, they were designed according to a "hair trigger" "-5 cents" configuration, per The Atlantic. Five percent more plutonium, and flash: the core went "supercritical." Neutrons hit neutrons, and those neutrons hit more neutrons, and the exponentially growing cascade yielded tremendous radioactive and thermal energy. Conventional explosives were needed to cause the typical a-bomb mushroom cloud blast.

Dahglian and Slotin wanted to find an unconventional way to reach a supercritical reaction using thick materials such as beryllium. The neutrons would bounce off and back into the core. Once enough were trapped: flash. This wouldn't cause an explosion, but it would tell them how to build the best bomb for the least materials.

On August 21, 1945, Dahglian was building a barrier around the core using tungsten-carbide bricks. He dropped a single brick by accident, and the core went supercritical. There was a bright blue flash, a rush of heat, and 25 days later he was dead. The sleeping dragon's tail had been tickled.

The demon core's final revenge

The very DNA inside Harry Daghlian's cells had been shredded by gramma particles. "He died in service to his country," his headstone says. And Louis Slotin, who'd stayed with Dahglian in the hospital, simply continued the same experiments. Except he took even more unnecessary risks. "Shirt unbuttoned and sunglasses on" as The Atlantic describes, he demonstrated his own version of "tickling the sleeping dragon's tail," a phrase coined by physicist Richard Feynman. Slotin slid a beryllium half-sphere on top of the demon core, slowly, without a failsafe spacer, using only his bare hands and the edge of a flathead screwdriver to keep it from being sealed.

On the final test of the final day, Slotin dropped the screwdriver and the beryllium cap slid into place. The same blue flash, the same rush of heat, and within "a few tenths of a second" Slotin had yanked the cap off. "Well, that does it," he said, per Science Alert, and ordered the other scientists to record where they were standing. Nine days later he was dead. Both men died on the 21st of the month, both on Tuesdays, and both in the same hospital room.

The core, originally dubbed "Rufus," as The New Yorker states, was afterwards referred to as the "demon core." It had been scheduled for detonation in the Bikini Atoll in a series of post-war tests, but in the summer of the following year, it was melted and reabsorbed into America's arsenal.