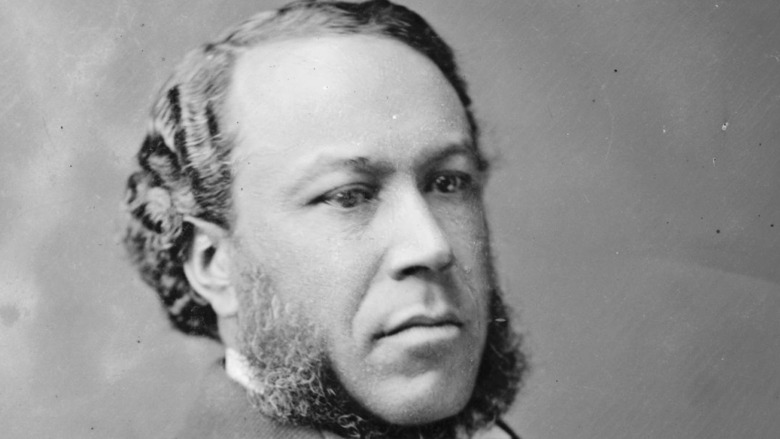

The Untold Truth Of Joseph Rainey, The First Black Congressman

Postbellum Americans committed to their racism found a formidable opponent in Joseph Rainey, the first Black person elected to the House of Representatives. Rainey served in Congress throughout the 1870s, tirelessly arguing for civil rights and fighting against the Ku Klux Klan. To the frustration of white supremacists, he was more than an intellectual match for his white colleagues, holding the floor with eloquent speeches that dived deep into sources like Shakespeare and Plato (via the U.S. House of Representatives).

Rainey was known for using the floor to advocate against the indignities Black Americans suffered in their daily lives. "Why cannot we stop at hotels here without meeting objection?" he once demanded (per Smithsonian). "Why cannot we go to restaurants without being insulted? ... we have been sent here by the suffrages of the people, and why cannot we enjoy the same benefits that are accorded to our white colleagues on this floor?"

Most significant to Rainey's career was the passage of the Ku Klux Klan Act, a law that empowered President Grant to fight white supremacist terrorist groups in the south (a resounding success, it effectively dismantled the KKK for a generation). When another congressman asserted that the act might be unconstitutional, Rainey's reply was rather forceful: "Tell me nothing of a constitution which fails to shelter beneath its rightful power the people of a country!"

Even more fascinating than Rainey's time in Congress, though, was his rise from humble roots as the son of a slave.

Rainey was forced to fight for the Confederacy

Rainey grew up the son of a slave in Charleston, South Carolina. Rainey's father, however, ran a business as a barber on the side, and eventually earned enough money to buy his family's freedom (via Voice of America). When Rainey reached adulthood, he went into business as a barber himself; however, Charleston's laws still treated him as a second-class citizen, requiring him to have a white "guardian" to live in the city, and threatening him with prosecution if he was caught without the papers proving his freedom.

When the Civil War broke out, Rainey was forced into the Confederate military — first building defenses for Charleston, and then serving as the steward for the navy. In 1862, Rainey had had enough, and escaped to Bermuda, where slavery had been abolished 30 years prior (via the Bermudian Heritage Museum). During his island exile, he read many of the classics of Western literature.

After the war ended, Rainey could have remained in the relative safety of the island, but chose instead to return to serve in South Carolina's constitutional convention, run for Congress, and serve in his state's treasury department. In that time, he never lost sight of the fight for Black Americans' rights.

The United States House of Representatives relates that he told his colleagues in the House, "I can only raise my voice, and I would do it if it were the last time I ever did it, in defense of my rights and in the interests of my oppressed people."