Things We Still Don't Know About Our Own Solar System

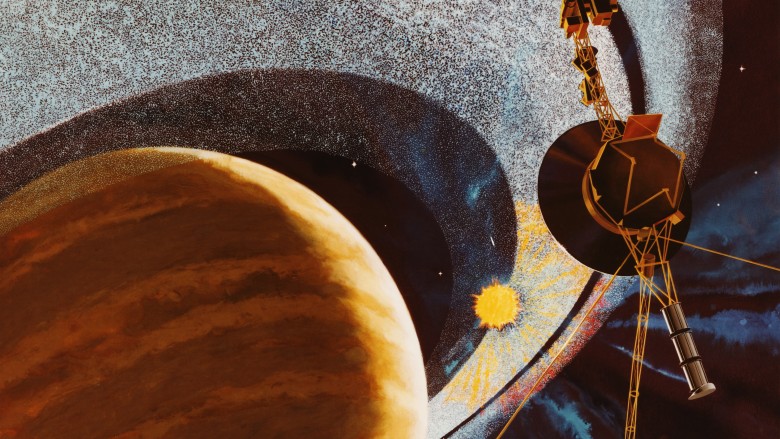

Since the days when many of us were making crudely-painted Styrofoam models of our Solar System for middle-school science class, what we know about our galactic neighborhood has changed, and more than just a little bit. As we discover more and more about our place in space, new answers seem to only lead to new questions — many of which are perplexing even the world's best astronomers.

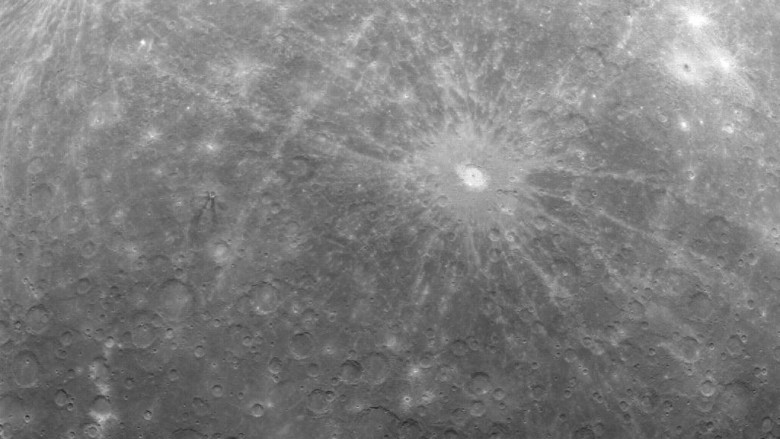

How did the spider on Mercury form?

Appropriately named after the swiftest and speediest of Roman gods, Mercury races around the sun at nearly 31 miles per second. In terms of temperature, however, Mercury goes from zero to 100 (or, more accurately, -290 to 800 Fahrenheit) real slow — a one day-night cycle equals nearly 176 Earth days. It's also quite the handsome planet. Images from the Messenger spacecraft show the closest planet to the Sun sporting deep blues, rusty oranges, and the impressive Caloris Basin.

Messenger also revealed something mysterious about the impressive speedster: a 41-kilometer-wide crater with a massive array of grooved valleys radiating out from it called "The Spider." The Spider lies within the 3.8-billion-year-old Caloris Basin, but is visually confusing. The Spider's body doesn't quite match up to its legs, as the central crater is off-center in relation to the valleys extending out from it. Scientists still don't have a definitive answer explaining the creation of this unique landmark.

How did Mercury itself form?

We have ideas as to how planets form, but we don't have actually know, in any real way, how Mercury came to be.

It was once believed that Mercury started out like its sisters, Venus and Earth, but its close proximity to that massive fireball we call the Sun roasted away the outer layers. Another theory proposed that Mercury was heavily damaged when it smashed into another planetesimal (a piece of a planet). Today, we can pretty much scrap those ideas, as both the solar-roasting and collision theories would require that Mercury be depleted of potassium, thorium and uranium. However, Messenger found that the ratio of these elements on Mercury is actually similar to Mars, Venus, and Earth — essentially disproving the two most prominent formation theories, and leaving us more confused than ever as to the origins of Mercury.

"What's the best alternative theory?" asked Time magazine in a piece about the "riddle" of Mercury's birth. "And the answer — wait for it — is, 'who knows?'" If science is all about truth, "who knows" is as scientific an answer as we got.

Is there anything between Mercury and the sun?

For a long time, astronomers were confused as to why Mercury has such an eccentric orbital motion — which differed from their calculations. The most prominent theory put forth by French mathematician Urbain Le Verrier was that a mysterious, yet-to-be-discovered planet existed between Mercury and the Sun, a planet he and others coined Vulcan. Unfortunately, astronomers never found evidence of Vulcan's existence, and Albert Einstein completely blew up Vulcan's spot with his theory of general relativity.

Scientists have made enough observations to reasonably conclude that there is no planet-sized object between Mercury and the Sun, but there are likely asteroids orbiting in that space. Asteroids that orbit completely interior to Mercury would be called vulcanoids, but none have ever been found. In fact, no asteroid larger than 6 meters across has been picked up by NASA's STEREO spacecraft. The closest we got to finding a vulcanoid is 2007 EB26, which — unfortunately — spends most of it's time chillin' outside Mercury's orbit.

Still, we're not writing off some mini-Vulcans just yet. They kinda sound adorable, like Tribbles.

Why is Miranda so ugly?

We're not talking about Mass Effect's dark-haired bombshell Miranda Lawson, modeled after and voiced by actress Yvonne Strahovski. No, we're talking about the Miranda that hovers around Uranus. (Again, clearly not Strahovski.)

Only one-seventh as large as our own Moon, Miranda looks like she's had a pretty rough go, but scientists are unable to come to an agreement as to why this moon looks so beat up. According to NASA, some scientists speculate Miranda was involved in a massive collision — breaking apart before being haphazardly reassembled — though it's more plausible that Miranda's surface has been repeatedly subjected to a barrage of meteor strikes, causing slushy water to rise to the surface before refreezing.

Whatever the reason, this particular Miranda certainly doesn't have it going on in the looks department. We'll therefore award Lawson the title of most attractive Miranda in our solar system. Lambert is #2.

What are those weird spots on Uranus?

Yeah, you'll probably want to get those checked out. Get it? Spots on Ur-anus? Ha! Ah, we're just playing — no more butt jokes.

Spots tend to pop up on Uranus at random intervals like a bad rash, always seeming to surprise scientists. In 2006, the Hubble Space Telescope was the first to officially sight a dark spot on the smooth surface of Uranus, roughly 1,100 miles by 1,900 miles in area. Then, in 2011, a bright white spot surfaced, which ended up being merely a giant cloud of fart gas, AKA methane. We now know these mysterious spots are most likely storms, but scientists are perplexed by the fact that these storms are still occurring — having previously assumed that it was no longer springtiiiime for Ur-aaaa-nuus.

But seriously ... if these spots shouldn't be showing up — why are they? Maybe Uranus really should see a doctor.

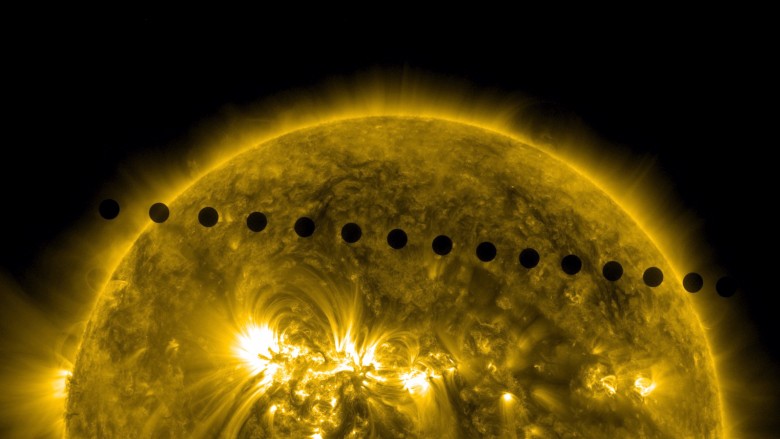

Why does Venus glow?

Earth's evil twin sure does have her secrets, one of which is the mysterious reason behind her green glow.

We know why the Earth glows green on occasion: its magnetic field deflects the Sun's occasional bursts of high energy particles, causing atmospheric gases to glow in what we know as the the Aurora Borealis. Our sister Venus, however, doesn't have a global magnetic field. Thus, by all rights, she shouldn't be glowing. (She's bright enough as is, and that ain't jealousy speaking.) Venus even glows on her night side, too. Seriously, stop being so pretty!

As awesome as it would be to learn that there was an alien civilization beneath the gas clouds of Venus, we know that's not the case. The most plausible theory explaining our sister planet's glow is that there's a traceable amount of nitric oxide (NO) in the atmosphere, signifying chemiluminescence. This means that the Sun's ultraviolet light breaks up molecules on Venus into atoms and smaller molecules, allowing them to reconvene while giving off excess energy as light.

This, however, doesn't provide all the answers — and scientists are still hoping to uncover any correlations between Venus's various nightglows. It can't be just a pretty face, after all.

How did life originate in our solar system?

As selfishly satisfying as it would be to learn that life evolved first and solely on our planet, we cannot claim this as a certainty. In fact, it's totally possible that — a long time ago — life was delivered to this planet.

Perhaps you've heard of panspermia? Panspermia is the theory that Earth was inseminated by some foreign body, be it bacterial spores aboard an invading comet — or even aliens! (Prometheus, anyone? We're not saying it's aliens, but ...) Scientists cann't definitively rule out the idea that life was brought to Earth from somewhere else, due to the lack of any conclusive evidence for or against this theory.

From the evidence we do have, scientists are pretty sure the oldest form of life on Earth is a single-celled organism called archae — hardy little bastards able to withstand even the harshest of environments. But were they really the first, or did some catastrophe wipe out more advanced, already-evolved organisms, leaving only archae behind? Better yet, did life even evolve first on Earth, or are we late to our own Solar System's game? If there is truly an ocean of liquid beneath the surface of Jupiter's moon, Europa — perhaps there's life there, too. And when we speak about Mars, we're still looking for some fossil evidence of past Martian life that could have preceded life on our planet. Thankfully, whatever used to live there never blew up the Earth because we were obstructing its view of Venus.

There's a lot about Europa we don't know

Europa is one mysterious lady moon. For starters, we don't know how thick her icy layer is. According to R. T. Pappalardo of the California Institute of Technology's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Europa either has a "thin" layer of ice or a "thick" layer of ice (go figure) — crucial information regarding the moon's potential habitability. There's actually even the potential for a "hybrid model" of both thin and thick ice (again, go figure). Secondly, Pappalardo notes that we really don't know much about Europa's stress patterns, or how to crack her icy shell. Moreover, we don't know what the non-ice components of her shell are, or if her shell is convecting.

Furthermore, Pappalardo illustrates that we don't know how the moon's chaotic regions were formed, nor if liquid water is involved. We don't know how active she is, if her activity has changed over time, or if her rocky mantle is hot. We don't know how she reacts to her environment, and we don't know — perhaps most importantly — if her ocean is habitable and/or inhabited. All things considered, it seems like we know almost nothing about Europa!

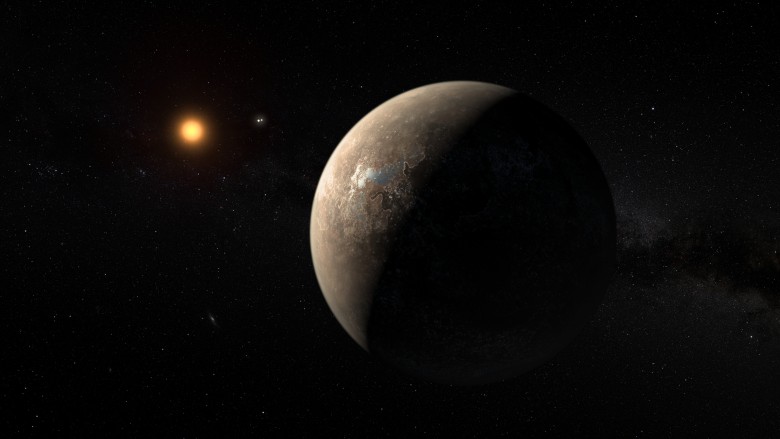

Is our solar system unique?

The short answer is: not really. According to research, we're actually pretty typical — our gas giants are nothing to write home about, and our Sun is both older and younger than half the stars in the Milky Way. We are the C students of space.

Our planets do, however, have more regular orbits than most other systems, likely due to the fairly large number of planets orbiting our Sun. Additionally, our solar system seems to lack close-in planets. However, this may only seem uncommon, as it's easier to detect large planets orbiting close to stars — meaning there may be other systems lacking in small close-in planets, like ours, that we just don't know about. But what certainly makes us weird is how we don't have any super-Earths — planets with 1 to 10 times the mass of Earth. Super-Earths are actually quite common in other systems, making our lack of them more than a bit strange.

Even though a lot of research suggests that we aren't a particularly special solar system, there's still quite a bit of science arguing the opposite. For example, it's odd that Jupiter orbits so far away from the Sun. Still — even with our unique features — the sheer number of stars out there means that we're probably not all that rare, and there are plenty of other C students out there to play with.

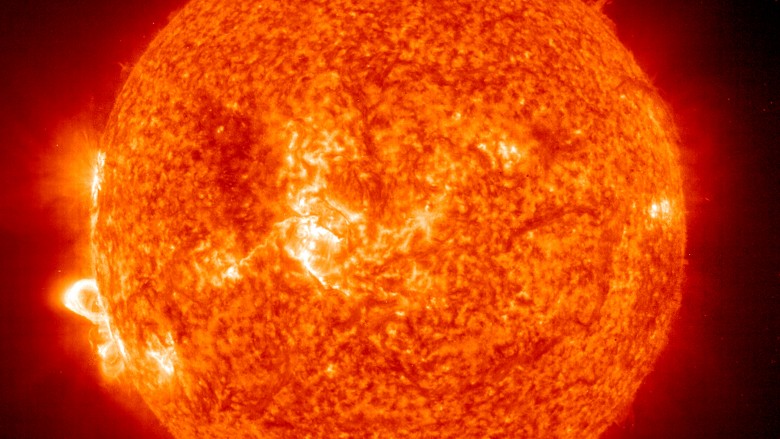

Why is one of the Sun's poles colder than the other?

The Sun may be hot, but one of its poles is hotter than the other — by 7% or 8%, to be exact — and scientists don't really know why. Not that it matters to us — we'd roast no matter what pole we visit.

Some speculate that the Sun's polar temperature discrepancy isn't too dissimilar from Earth's. On our planet, the South Pole is colder, on average, than the North Pole. This isn't that surprising, once we consider the way in which land is distributed on our planet — and while the Sun has no land, it does have magnetism. The cool spot on the Sun follows the Sun's north magnetic pole — which actually flips on occasion!

Still, it's not exactly easy to measure the Sun's precise temperature discrepancies — what with it being a 27-million-degree ball of gas — so scientists cannot definitively solve the energy source of our solar system's polar mystery. We'll just have to send an astronaut there to find out.