The Most Dangerous Sharks In The World

Whenever prehistoric predation gets brought up, people typically think of carnivorous non-avian dinosaurs first. What many don't realize is that a far more successful group of hunters showed up millions of years earlier — sharks. Based on fossils, the first "true" sharks appeared some 420 million years ago, but the Natural History Museum suggests they may have popped up even earlier than that. To put things into perspective, that's over 20 million years before there were even trees.

Experts say that diversity was probably the biggest reason behind sharks' resilience. Different types of sharks could live in different parts of the ocean and thrive on different prey, pretty much ensuring their group's survival. The Smithsonian Ocean Portal estimates that there are over 500 species of sharks in the world today. Surprisingly, only about a dozen of them have killed humans unprovoked since 1580, based on the Florida Museum's International Shark Attack File. Considering how humans kill nearly 100 million — that's not a typo — sharks per year (via National Geographic), humans are actually a bigger threat to them than they are to us.

That said, it's easy to see why humans fear sharks. Pop culture's unflattering portrayal of sharks notwithstanding, there are many reasons why these cartilaginous fishes are typically the top predators in their ecosystems. And there's no better way to explore said reasons than to examine how some of the most dangerous species exemplify them.

Shortfin mako shark: the swiftest-swimming shark

As far as swimming speed goes, every other identified shark species eats the shortfin mako's dust. Clocking in at 45 mph (via Oceana), this swift swimmer is the world's fastest shark. Even fleet-finned fish like the Atlantic bluefin tuna (43 mph, as per the World Wildlife Fund) would not be much of a problem for it. One glance at this species would tell you why — its hydrodynamic shape, pointed snout, triangular back fin, and crescent-shaped tail fin make it an efficient underwater navigator (via the Florida Museum).

Shortfin makos can keep their body temperature high even in cold waters, thanks to how their blood vessels are arranged — a characteristic they share with true tunas and other shark species. It's no surprise that the shortfin mako has no natural predators. In its ecosystem, it dominates the food chain. In fact, a shortfin mako delivered the strongest shark bite ever measured — a whopping 3,000 pounds of pressure (via Newsweek). Above the water, though, it's a different story.

The shortfin mako is among the most extensively studied shark species. Unfortunately, as Mongabay reports, this has not spared it from finding its way to the Red List of the IUCN as an endangered species. Based on official records, it has only ever killed one person unprovoked. Meanwhile, the demand for its meat, fins, and liver oil have made it one of the world's most prized game fishes, bringing it closer to extinction with each passing year.

Spinner shark: the slim-bodied aerial spinner

You're on a beach somewhere in Florida, sitting and relaxing near the shore. One moment, you're admiring the way sunlight bounces off the water's surface. The next, you're watching three gray sharks (thankfully at a safe distance) spinning in mid-air and failing spectacularly at synchronized ballet.

Named after their peculiar feeding behavior (via the Florida Museum), the slim-bodied spinner shark likes to swim through schools of small fish, spinning and snapping its pointed jaws. It often does so with enough force to leap as high as 20 feet above water, grabbing as much food as it can along the way.

To date, there have been no recorded incidents of anyone getting bitten to death or eaten by a spinner shark. Given its small, narrow, triangular teeth (via the Shark Research Institute), it's an optimal piscivore and not much of a threat to humans. However, it has been known to bite people, with 16 non-fatal and unprovoked attacks under its name. Spearfishing divers seem to get its attention, for some reason. Furthermore, its coloration sometimes causes confusion among fishers and divers. On multiple occasions, it has been misidentified as a similar-looking species, the blacktip shark.

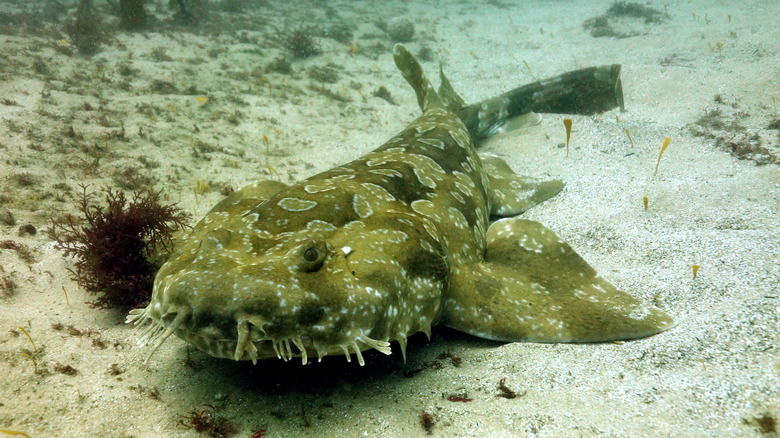

Spotted wobbegong: The weird shark that bites down hard

A strange-looking shark with an equally odd name, the spotted wobbegong is a well-camouflaged predator that lives in the warm, coastal waters of Australia. According to the Georgia Aquarium, the spotted wobbegong prefers to sleep in caves or on coral or rocky reefs during the day. It hunts during the night. While its main method of hunting remains largely unknown, experts have suggested that it lures its targets with the soft, fleshy tassels lining its mouth, as it lies waiting on the sandy bottom of the ocean (via Animal Diversity Web).In some cases, however, scientists have observed the spotted wobbegong stealthily sneaking up on its prey.

Don't let the spotted wobbegong's docile appearance and sluggish demeanor fool you, though. Hidden within its lobe-lined snout are rows of enlarged, elongated fangs, according to the Florida Museum. Because it's so great at hiding, unsuspecting divers sometimes step on it. This rarely ends well for them, as the spotted wobbegong has a habit of swiftly retaliating. This shark's bite is so strong that some victims lost their limbs after being attacked. There are even reports of wobbegong biting down hard on fishing boats. However, a large number of bites attributed to the spotted wobbegong may have actually been from a different wobbegong species, as it can be occasionally tricky to tell them apart.

Bronze whaler shark: The copper, catch-copping carcharhinid

When Jahmon Wilson went spearfishing at a New Zealand surf and dive spot in January 2021, he probably wasn't expecting to get up close and personal with a bronze whaler shark. It's also unlikely that he was expecting the shark to yank his hard-earned catch from his hand — but odds are he was grateful it didn't end up yanking his hand off instead. In an interview with Stuff, he called the experience an adrenaline dump. "I knew it was just going for the fish, I knew that I wasn't in any real harm unless it took my hand with it."

Described by the Shark Research Institute as an active, fast-moving species, the bronze whaler, also known as the copper shark, ranks 10th in terms of the number of unprovoked attacks on humans (via the Florida Museum). Because of its resemblance to other requiem sharks, it can sometimes be challenging to identify. However, it's the only requiem shark that dwells in temperate instead of tropical latitudes.

Then again, not everyone who has met a bronze whaler shark turned out to be as fortunate as Wilson. In the past, there has been at least one recorded fatality resulting from a confirmed bronze whaler shark bite.

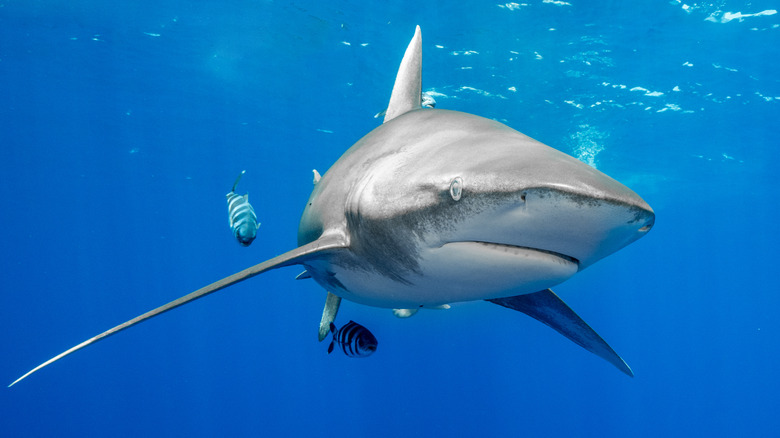

Oceanic whitetip shark: A history-making hunter

Oceanic whitetip sharks have earned a bit of a nasty reputation with the nautical crowd. The Florida Museum says that it is "often the first species seen in waters surrounding mid-ocean disasters." They're drawn to downed planes and shipwrecks, seemingly eager to turn any survivors into a quick meal. It's also the species that the majority of shark experts point to when they think about the 1945 sinking of the USS Indianapolis, which has the dubious distinction of being the worst shark attack in history. According to Smithsonian Magazine, up to 150 of the Indianapolis' crew members could have been eaten by oceanic whitetip sharks after torpedoes destroyed the ship. In the end, only 317 out of the 1,196 people aboard survived the tragedy.

Unfortunately, society's generally negative perception of the species may have had disastrous consequences — and worse, humans may never even realize their full extent. A National Geographic article highlights the massive knowledge gap about oceanic whitetip sharks, while revealing that it wasn't until 2010 when international fishery organizations started taking action to conserve the species. Studies have shown a tremendous drop in oceanic whitetip shark populations in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, due to them being hunted for their fins and getting accidentally caught in commercial vessels' fishing traps.

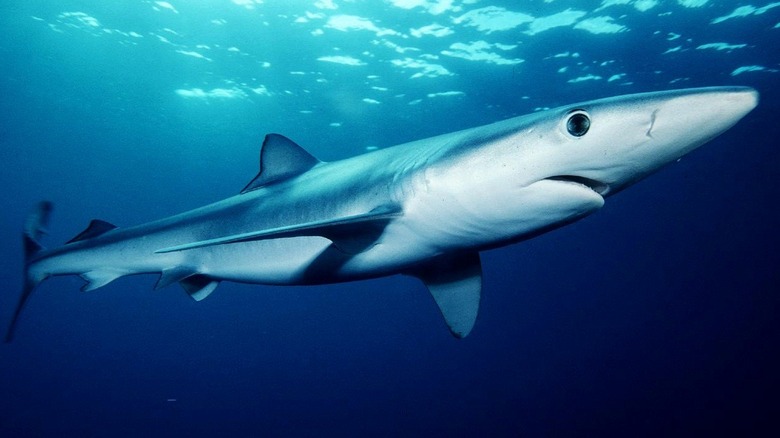

Blue shark: beautiful, blue, and dangerous, too

Sporting brilliant blue coloration that makes it stand out from other shark species, the blue shark is quite a sight to behold. According to Oceana, the blue shark is a curious predator that thrives in a wide range of habitats. Its triangular, saw-edged teeth are well-suited for its diet of small cephalopods, open-water fish, and even seabirds that they grab from the water's surface (via the Shark Research Institute).

Due to their innate inquisitiveness, blue sharks have been observed to approach spearfishers, divers, and drifting survivors of shipwrecks or plane accidents. They reportedly become even more persistent when they detect spearfishers hauling in food. However, the blue shark isn't necessarily an aggressive species. Rather, it's a curious one that likes to sneak in a bite after circling potential prey. Unfortunately, the one-two combination of chompers and curiosity make the blue shark an unexpected hazard to humans — in terms of unprovoked fatalities, they rank fourth among all known shark species, based on the International Shark Attack File.

The blue shark is known to be widely distributed across the world and used to be nearly ubiquitous. Because of the high (and illegal) demand for their fins and how frequently they accidentally get caught in fishing nets and traps, the global blue shark population has greatly declined over the years.

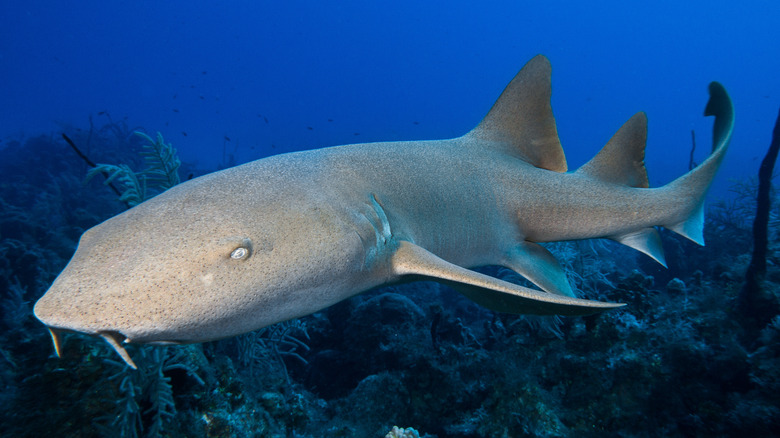

Nurse shark: a slow-moving, smooth-skinned suction feeder

When you hear the words "nurse shark," what's the first thing that comes to mind? Medical attention for a shark bite, perhaps? According to National Geographic, this shark's strange name most likely came from hurse, meaning sea-floor shark in Old English. It's a word that perfectly captures what is known about this shark's behavior — a somewhat sluggish fish that hangs out at the bottom of the ocean.

Growing up to 14 feet long, nurse sharks are a fixture in certain shallow areas of the eastern Pacific and western Atlantic. While it used to be in no particular danger, it is now classified as a threatened species under the IUCN Red List. Much like the wobbegong, it prefers to take things easy during the day but becomes an active hunter at night (via the Shark Research Institute). It may not look like much, but this suction feeder is actually a powerful swimmer capable of "walking" on the ocean floor with its pectoral fins.

Nurse sharks also have surprisingly strong jaws, the sheer strength of which some divers have had the misfortune of experiencing firsthand. According to the Florida Museum, its strong jaws — lined with thousands of serrated teeth — can clamp down on you hard like a vise if you make the mistake of disturbing it or stepping on it. In other words, if this shark bites you, chances are you'll need to see more than just a nurse.

Bull shark: an aggressive, territorial brute

In 1916, a series of shark attacks took place over 12 days along the shores of New Jersey. According to the Florida Museum, these five "Jersey Shore attacks” claimed the lives of four people — and while the true identity of the species responsible has not yet been (and probably never will be) conclusively determined, evidence points to the brutish bull shark as one of the culprits.

With 92 non-fatal unprovoked attacks and 25 fatalities under its name (via the International Shark Attack File), this species is the world's third most dangerous shark. In fact, some consider it to be at the top spot, believing that it may be responsible for even more attacks. Bull sharks are reportedly so aggressive and territorial that numerous aquaria don't even want to feature them, fearing that they'll annihilate the other animals inside their tanks (via Animal Diversity Web).

Oceana noted their ability to easily move from saltwater to freshwater and back when searching for prey. An article on BBC explained that bull sharks rely more on their noses than their eyes while hunting in shallow waters and are able to sense their targets' electrical fields via electroreception. Meanwhile, some have observed how they tend to approach boats, believing it to be a sign that they're always hunting for food. This may also explain why they occasionally mistake humans for chow, often testing with an "exploratory" bite that delivers nearly 1,350 pounds of force (via Newsweek).

Gray reef shark: sometimes social, always active

What's worse than randomly encountering a shark? For some, it would probably be encountering an entire group (or "shiver") of sharks. If that's the case, then you should mentally prepare yourself if you ever think of daytime diving in the waters of the Marshall Islands, because you're bound to run into a notoriously aggressive population of gray reef sharks (via Animal Diversity Web).

According to the Shark Research Institute, gray reef sharks tend to form groups in lagoons and reef passes while the sun's up. Come nighttime, though, they split up, becoming individual hunters. When this happens, they no longer have the advantage of strength in numbers. Thus, the chances of them becoming more defensively aggressive (and more likely to bite) go up, says the Florida Museum. These sharks have extremely sharp senses and will perk up when they feel a fish in its death throes (i.e. instant food) or catch a whiff of blood in the water.

Gray reef sharks sometimes display territorial behavior when they come face to face with a human that may seem threatening to them. When this happens, they arch their backs, raise their snouts, and lower their pectoral fins, a sign that they're preparing to attack. They often retreat immediately but sometimes bite before leaving. Over the last four centuries, they've been responsible for 8 attacks and 1 fatality.

Tiger shark: like its land-based namesake

If the name "tiger shark" fills you with a sense of dread, well, it should. Statistics say that it's the second most dangerous shark species, having caused 97 unprovoked non-fatal attacks and 34 deaths (via the International Shark Attack File). Considering how it's one of the largest known shark species in existence (via the Florida Museum), it's not surprising that it's part of the notorious "Big Three" of potentially dangerous sharks.

According to the Australian Museum, one can find tiger sharks in warm, coastal waters. Sporting large, finely serrated teeth, powerful fins for swimming, and vibration detectors on their sides (via How Stuff Works), tiger sharks are slow-moving but incredibly successful ambush hunters capable of quickly grabbing their targets. Aside from the gray stripes running down their bodies, tiger sharks are also well-known for their tendency to eat pretty much anything — whether it's a sea turtle, a seagull, beer bottles, or even the entire head of a horse (via the Deccan Chronicle), tiger sharks definitely live up to their reputation as the trash cans of the ocean.

Surprisingly, however, many close encounters with tiger sharks didn't instantly lead to underwater violence. In fact, a 2005 work cited by the Florida Museum described them as "often curious and unaggressive when encountered." Still, that's no reason to fool around or feel complacent when this apex predator gets up close and personal.

Sand tiger shark: a scary-looking sea bottom hunter

One look at a sand tiger shark would be enough to make even the bravest diver swim away as fast as possible. With its huge body, pointy snout, menacing eyes, and a mouth full of sharp snaggle teeth protruding in all directions even when it's closed, this fearsome shark looks like a rocket wearing a demon mask.

Like quite a few of the other sharks on this list, the sand tiger shark is a nocturnal predator that sometimes hunts alongside other sharks. Its diet primarily consists of small fish, cephalopods, and crustaceans, depending on what it catches near the bottom of its habitat. Sand tiger sharks have also been known to attack full fishing nets and even steal fish caught by spearfishers (via the Florida Museum). According to the Shark Research Institute, when divers get close to it — or when it gets accidentally close to a diver — it will use its tail to generate a loud boom that rattles the poor victim.

Ironically, this species actually isn't that aggressive, according to National Geographic. Still, there are 36 verified accounts of it biting humans unprovoked. Some of these were spearfishers retrieving the fish they skewered. Fortunately, it hasn't killed anyone yet.

Great white shark: The biggest and baddest of them all

It would be a mortal sin for any list of dangerous sharks to leave out the shark that partially inspired "Jaws" (via Smithsonian Magazine). When it comes to violent interactions with humans, no other shark species comes close to the great white shark. Based on official records, this terrifying titan was responsible for at least 290 unprovoked non-fatal attacks and has killed at least 52 people.

Said to grow up to 23 feet (via the Florida Museum), a great white's bite can deliver nearly 2,250 pounds of force (via Newsweek). These aquatic apex predators possess a streamlined shape for swift swims, strong tails that let them swim up to 25 mph, and large, jagged teeth. A feature on BBC explained great whites' preferred method of attack — rising from the depths and chomping down hard on unsuspecting prey. Sometimes, they even wait for their prey to bleed out before proceeding with their meal.

Interestingly, studies have revealed great whites aren't the mean, man-eating murderers many think they are. For starters, scientists think they might not even like how humans taste (via The Guardian). Some say that attacks usually happen because swimming humans resemble seals, great sharks' favorite food (via National Geographic). Besides, given their declining numbers in recent years, it seems like even the most dangerous shark is no match for the world's most destructive species — humans.