The Truth About Starlite, The Material That Can Resist A Nuclear Blast

On October 5, 2020, NBC News reported that California passed a "grim milestone," namely, over 4 million acres of the state had been incinerated by unquenchable wildfires. Even a few weeks prior on September 15, CNN reported that an area "the size of Connecticut" had been razed. Houses were evacuated, neighborhoods engulfed, and folks turned their eyes to the sky to watch an orange-red nimbus of flames and soot-black plumes tumble their way toward their homes, their living rooms, their families, their entire lives.

So what if that whole scenario could have been averted, or at least greatly abated? Not the ever-worsening, climate change-induced wildfires that exacerbate California's already dry tendencies. But the loss of decades worth of mortgages, the salaries that went into them, and the overall ruination that forced, as Reuters reported, half a million to flee their homes, leaving 20,000 permanently displaced like refugees in their own state.

What if, in fact, it could have been averted with something as simple as a bucket of plaster lightly brushed across the exterior siding of a house. And not some magic material — not really, not chemically — but something that came standard with homes, or at least could be bought at Home Depot for a reasonable price? That's it. Flames sweep over a house, and people are so safe that they can just sit there and not even feel warm.

Sound unbelievable? Enter Starlite: the intumescent material that never was, and one that could still change the world.

The shocking 'egg test' at Tomorrow's World in 1990

The BBC used to run a program called "Tomorrow's World," which aired all the way from 1965 to 2003. It was kind of a televised tech expo where hosts with mics sauntered across stages between demonstrations of up-and-coming technological innovations, the kind of show pastiched in the "Iron Man" movies when Tony Stark spreads his arms wide to an adoring crowd speckled with camera flashes.

On March 8, 1990, per the BBC, viewers who tuned into "Tomorrow's World" caught a demo that seemed actually, remarkably, physically impossible. The host, Peter Macann (1983-1991), turned a blowtorch on an egg. The egg, though, didn't erupt, explode, or anything. It just stayed there atop a pedestal, for minutes on end, with a 1,200-degree Celsius flame trained on it. When the demo was over, Macaan picked up the egg, which was somewhat scorched but immediately cool enough to touch, cracked it open, and out fell a perfectly raw yolk. You can watch the whole thing on YouTube.

It wasn't a trick, although it certainly looked like magic. The egg had been coated with a material dubbed "Starlite" by its creator, Maurice Ward, a "lady's hairdresser" from the small, coastal town of Hartlepool, England, about 45 minutes south of Newcastle. Ward, an excessively secretive person, and obsessively protective of his Starlite formula, had applied the material directly to the egg, himself, like paint, disallowing anyone else's involvement, before it was brought on stage.

Maurice Ward, hairdresser and Starlite's eccentric creator

Maurice Ward had been a hairdresser in Hartlepool for over 20 years, building his own business and even branching out into wigs, which he himself constructed. One of his daughters, Nicola McDermott, credits this turn toward chemistry and material sciences as Ward's eventual pathway to Starlite, per the BBC. Ward, for the record, was not any kind of formally trained scientist. He was, in his own words, "just an inventor that plays around," but who does it "different to the normal kind of person."

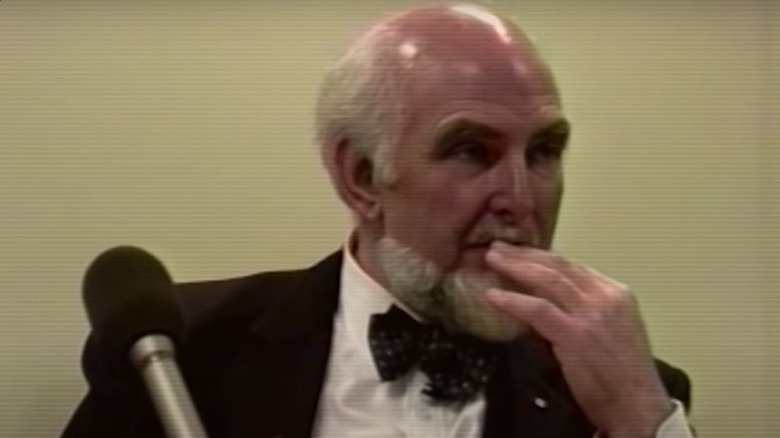

Ward and his "otherworldly" persona, as his friend Toby Greenbury described him, always appeared in public impeccably dressed, in bowties and colorful, three-piece suits, sporting a perfectly sculpted beard that wouldn't look out of place in a Brooklyn speakeasy in 2021. And Starlite, he stated — his creation — could withstand the thermal energy of 75 nuclear blasts.

Ward was inspired to take action following a flight disaster in Manchester in 1985, when an engine caught on fire during take off and 55 people died not from fire, but from smoke inhalation, as I, Science explains. Ward wanted to develop a product to deal with that kind of situation, and set off concocting chemical compounds in his backyard, setting things on fire and watching them burn. Keith Lewis, former scientist with the Ministry of Defense, states that one day, almost by accident, Ward noticed a fragment of trash consumed in flames but not alight.

Countless industrial and military applications lost

Make no mistake: industries and militaries were very interested in Ward's invention, which was still only a compound, scribbled on paper in Ward's home workshop, and otherwise residing in his head. NASA, NATO, Boeing, the Ministry of Defense (MOD) and more clamored for Ward's attention, and companies worldwide strove to strike deals with him. Ward though, for his part, was an incredibly stubborn, difficult person, eccentric, not at all business-minded, and utterly fearful that someone would try and steal his ideas, or take his creation out of his control (via KQED).

As Keith Lewis, former MOD scientist, told the BBC, Ward wanted someone to just dump £10 billion (over $14 billion) on him and leave him alone to work. Ward is recorded on video saying directly to potential investors, "You ain't gonna pinch it," and also bullying his daughter Carrie, in public, during a demo when she suggests that the Starlite formula could be sold to someone who could develop it into an actual, commercial product. Ward's other daughter, Nicole, confirmed that their father could be quite argumentative and controlling.

Investors went so far as to conduct simulations using 4-kiloton conventional explosions at the Atomic Weapons Establishment in the U.K., and the White Sand Missile Range in New Mexico (via Big Think). Starlite-painted materials survived, slightly charred, intact even to this day. And yet, no one was ever able to make a deal with Ward. Interest waned, and Ward himself vanished from the public eye.

Somewhat recreated in 2018 from common household products

Mark Miodownik, professor of materials at University College London, conducted his own tests on Starlite, per the BBC, when Ward's daughters visited his lab in 2012. Starlite acts like paint; it's a white, viscous liquid that you apply to an object and let harden. It's essentially a "low-density foam made of high-carbon material." Carbon and its derivatives are highly heat resistant; this is why they're so dangerous in the atmosphere. Keith Lewis, former MOD scientist, recollects how early experiments with Starlite samples — including shooting it with lasers — showed that Starlite is essentially a reactive material. The bigger the pulse of heat, the more Starlite reacts, chemically, and the better it works.

After the BBC released its documentary on Starlite in 2018, some folks tried to reverse engineer its formula, such as YouTuber NightHawkinLight (real name: Ben). In his demo video on YouTube he holds in his bare hand what looks like a doughy piece of bread. He points a blowtorch at it, flips it on, and out shoots a 10,000-degree flame for almost 30 seconds. No burns, no pain. The material isn't even hot to the touch.

Ben, on the BBC, said he was inspired by Pharaoh Snake fireworks, which "decompose into carbon when heated." Another chemical fills the material with gas bubbles that create a volume of air separating the inner surface of the material from a heat source. How? Nothing more than flour, corn starch, sugar, and baking soda.

Thermashield owns the rights, passed on from Ward's daughters

In 2013, as reported by the BBC — the year after Ward's daughters visited Mark Miodownik — they sold Starlite to Thermashield, a California-based LLC, which, according to the Thermashield website, "started a friendship with Maurice Ward and his family" in 2008. CEO Rafael Silva's sole intention, per the Thermashield site, was to "help him [Ward] develop and commercialize his invention by promoting it where there was opportunity." Perhaps this is what it took for the highly protective and secretive Ward to trust anyone with his invention. Unfortunately, several years after this relationship began, and two years before Thermashield acquired every single one of Ward's notes, original materials, formula, and samples, Ward passed away in 2011.

Silva says that the homemade recreations on YouTube, such as NightHawkinLight's flour-corn starch-sugar-baking soda substance, are poor imitations. He states that the process matters, the order of how things are combined, per Ward's notes and his company's own experiments, not merely the ingredients. He says it's utterly complex, and uses components that are not accessible nowadays except using various certifications and manufacturing methods. Current "thermal barriers" and "intumescent paints" on the market — commercial substances that have similar properties to Starlite, such as those described on Promat — fail over time, whereas original Starlite-coated objects still resist heat 20-30 years later.

And the original "egg test"? Silva says that current intumescent paints work for about 1-5 seconds before the egg explodes.

Misunderstood genius, domineering hermit, or both?

So what is the lesson here? On one hand, we can draw (perhaps undeserving) comparisons to genius inventors like Nikolai Tesla, whose mere 30 patents, in comparison to rival Edison's 1,000 patents, don't at all reflect his brilliance. Edison, of course, was a ruthless businessman as much as anything else, and not only stole ideas from folks such as Tesla, but slandered Tesla in order to undermine his work, as The Washington Post describes. And so, one of Ward's foibles is revealed. He was, as the BBC said, "in over his head" when surrounded by massive government agencies and global military conglomerates.

Ward was also self-defeating and stubborn. He wanted everything — complete control — and so, got nothing. His daughters, presumably, financially benefited from their relationship with Thermashield, but otherwise, they could have undoubtedly reaped much larger benefits if only their father was more amenable to dealing with others. It's ironic that a hairdresser, a profession known for chatting up customers and requiring on-the-job affability, failed so miserably at the more social aspects of Starlite's business dealings.

All hope is not lost for Starlite, though. If Thermashield's seemingly genuine desire to promote Starlite proves successful, and they receive the investment they need, we might yet see a resurgence of Ward's original "mixture of 21 polymers and copolymers along with some ceramic material," as Big Think describes it. It's just a matter of two other ingredients that can't be reproduced: flexibility and trust.