Why The Sydney Opera House Was Nearly Not Built

Nearly 11 million people visit the Sydney Opera House in Australia each year to marvel at its creative sculptural design featuring interlocking shells, set on Bennelong Point. The iconic tourist attraction perched on a peninsula and surrounded by the Sydney Harbor almost looks like a sailboat about to venture into the sea. Its beauty belies the trouble the building faced during construction.

Slated to last for four years, the erection of the opera house started in 1959 and took 14 years and 10,000 construction workers to complete, according to the Sydney Opera House website.

The architect chosen for the project was the then-38-year-old Jørn Utzon of Denmark. The choice was the result of an international design contest that drew more than 223 entries from 28 countries in 1957. Utzon became so pressured by the project, however, that he left Australia during its construction, and never saw the finished building in-person.

The erection of the opera house faced problems from the start, according to Sydney Opera House's Our Story. The initial survey of Bennelong Point's geology was incorrect. Rather than containing Hawkesbury sandstone like the land that touched it, the peninsula contained random alluvial deposits filled with seawater, a substance that couldn't sustain the planned building's weight. To stabilize the structure, concrete and steel were inserted into the earth. Not only did this add unexpected expenses, but the plan also didn't fix the uncertainty of whether the unusual roof design, with shell-shaped panels topped by ceramic tiles, would work.

Money problems and arguments

New South Wales Premier Joseph Cahill supported the plan and pushed construction forward. The move proved prescient, since he died seven months later. Before he died, though, he asked the Minister for Public Works, Norman Ryan, to make sure the opera house got finished.

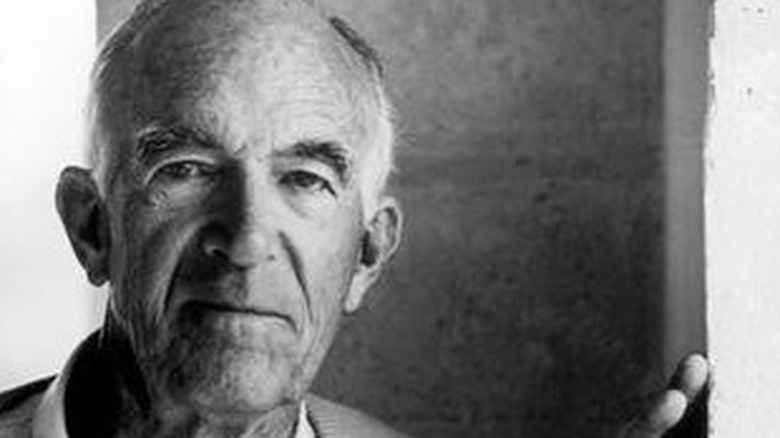

Utzon (pictured above) and his team worked on building the shell structure roof from 1958 to 1962, laboring over several designs, said The Sydney Opera House website. Eventually, Utzon's initial concept morphed into a technique dubbed the "Spherical Solution" that created the opera house's distinctive vaulted shells. But despite finding a way to build the facilities' unique roof, Utzon and Ryan fought about the project and its increasing cost — from 3.5 million pounds (about $28.6 million) to 13.7 (about $10.6 million).

Mashable reports that things worsened in May 1965 when a new Australian government came to power, headed by Premier Robert Askin, a critic of the opera house construction. The new minister of public works was Davis Hughes. Again, money caused contention, especially since the new leadership had promised the public that it would mitigate the opera house's rising costs and delays.

Hughes asked Utzon for drawings and a budget. But Utzon asked Hughes to allow him to "be in complete control of every detail," reported The Sydney Morning Herald, and asked for some leeway. Hughes remained firm: "Your wish to build the 'perfect' opera house is understood, but it must be accepted that all such proposals must be considered in relation to cost..."

An architect walks away from his vision

During a meeting between Hughes and Utzon, tempers flared, and when the architect threatened to walk away from the project, Hughes told him: "You are always threatening to quit," according to The Sydney Opera website.

The public supported Utzon by marching on State Parliament in March 1966 after it was announced he had resigned. Another rally and a petition followed, but the Danish architect never returned. Instead, Peter Hall, a rising local architect, took over. "I'm overwhelmed but I think I can finish the Opera House," Hall said to "The Daily Mirror," according to The Opera House Project.

And that he did. The opera house's grand opening on October 20, 1973, featured an appearance by Queen Elizabeth II, a helicopter salute, marching bands, and much fanfare, including Aboriginal actor Ben Blakeney greeting people from the top of one of the building's sails, according to the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. The first opera house production precluded this event, Sergei Prokofiev's "War and Peace," performed by the Australian Opera, which began on September 28.

An architectural marvel receives acclaim

Utzon did not attend the opening of the opera house. He did oversee the redesign of the building's reception hall in 1999, now dubbed the Utzon Room, according to Britannica. His son, Jan, also an architect, visited Australia to supervise and execute the work, said the New York Times. He also accepted an honorary doctorate for his father from the University of Sydney four years later. While there, he touched on how his father knew what the Royal Opera House looked like even though he never actually viewed it in person. "As its creator, he just has to close his eyes to see it," he explained, reported the publication.

Utzon received many awards for his work, including the Pritzker Architectural Prize, the field's highest honor, in 2003. He died in 2008 at the age of 90. "The Sydney Opera House constitutes a masterpiece of 20th century architecture," said the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) when it added the opera house to its World Heritage List in 2007. "Its significance is based on its unparalleled design and construction; its exceptional engineering achievements and technological innovation and its position as a world-famous icon of architecture."