Bizarre Facts About The Crusades

The Crusades were a pretty weird time. Granted, any period of history that involves not only intense religious fervor but seemingly unending bloody battles is bound to produce some pretty bizarre situations. And, given that the Crusades happened during the medieval period, when people had a lot yet to learn about the world outside of their particular fiefdom or duchy, things could get weird indeed.

According to History, the Crusades were a series of holy wars fought between Christian and Muslim forces as they sought to take control of the Holy Land and oftentimes the city of Jerusalem in particular. The First Crusade began in A.D. 1096, and subsequent conflicts continued until well into the 13th century. Even after that, some small attempts to fight it out took place here and there into the 1500s, when the pope began to lose the kind of temporal power necessary to command everyone to fight on behalf of the church.

While a look into a history of the Crusades will produce plenty of dates, names, and details about battles, that's not the whole story. The Crusades, it turns out, have a pretty strange side. From a divine goose to a mythical king holding the keys to the Garden of Paradise, these are some of the most bizarre facts about the Crusades.

Some crusaders followed a holy goose

It's safe to say that most medieval Europeans who went on a crusade to the Holy Land did so at the urging of a powerful, sometimes even charismatic individual. It could be a local lord, a religious leader, or even an especially fervent neighbor. But, as the religious intensity of the Crusades built, more and more people felt that it was their Christian duty to "free" the region — or at least gawk at the fighting and maybe take part in some adventuring and plundering opportunities. And the growing tide of interested folks, combined with a near-mystical mission, eventually produced some pretty weird leaders.

Namely, that one goose. According to The Medieval Magazine, the 1096 People's Crusade was an unofficial one that wasn't technically sanctioned by the pope. Yet, plenty of regular folks took part, with some even following a holy goose. In one version of the tale, a poor woman is trailed by one of her geese and, through a series of misinterpretations and misunderstandings, people began to believe that the divinely inspired goose was leading them.

Chroniclers jumped on the chance to paint the human followers as credulous fools. Who tries to follow barnyard fowl all the way to Jerusalem, anyway? By most medieval understandings, animals didn't have a soul and so couldn't begin to understand the Divine. The people's near-worship of the animal, which included even allowing it to enter into a church, was also deemed blasphemous.

Saladin did the crusaders a solid

Saladin is easily one of the most famous and complicated figures of the Crusades. Per History, Saladin was a Kurdish leader born around A.D. 1137 who would lead Muslim forces against the Christian crusaders and go on to be an even more powerful leader in the region afterward. He was also known for being a skilled negotiator and, according to some accounts, could be a noble and occasionally merciful opponent.

According to "Enquiring History: The Crusades," while besieging the crusader stronghold of Kerak in 1183, Saladin reportedly ordered his army to avoid striking a particular area of the castle. That's where the future Queen Sibylla of Jerusalem's younger half-sister, Isabella, was supposed to be having her wedding night with her new husband.

Sounds pretty chivalrous, but there may have been a more canny reason for Saladin to leave those crazy newlyweds alone. "The Leper King and His Heirs" posits that Saladin, thinking that he might capture the castle, wouldn't want to harm two important captives. It didn't matter, anyway, as Sibylla's forces successfully defended Kerak, and Saladin was forced to retreat.

A French soldier became a controversial mystic

One of the first major victories of the First Crusade was the siege of Antioch, but as the offensive began in 1097, things were looking pretty dire. Per Fordham University, the "siege" was actually a series of attacks meant to overtake the city, but as soon as they secured Antioch, the crusaders had to face renewed attacks from Muslim forces. It was in the midst of this tense time, likely with plenty of crusaders now questioning their original drive to reclaim Antioch and Jerusalem for their faith, that a miracle happened. Or did it?

Perhaps the strangest part of the siege was a man named Peter Bartholomew. According to Britannica, he was a French man who appears to have been a relatively low-ranking peasant. Bartholomew claimed that St. Andrew appeared to him and pointed him toward the location of the Holy Lance. Said lance was believed to be a spear that was used by Roman soldiers to pierce Jesus' side at the Crucifixion.

While many were skeptical, Bartholomew managed to get enough support to excavate inside a cathedral where — wouldn't you know it — he found the lance. It may have only looked like an eroded chunk of metal, but for many, it was good enough. The crusaders rallied around this holy symbol and kept fighting. Peter later agreed to prove himself through a trial by fire, said one account, whereupon he was badly burned and died soon thereafter.

People got weirdly interested in meteors and other things in the sky

Throughout history, astronomical phenomena like comets, meteors, and other heavenly objects moving in the sky have been interpreted as omens and portents by the anxious people watching below. Take the comet of 1517, which, according to PBS, was witnessed over the lands of Aztec ruler Montezuma II and inspired a sense of foreboding ahead of the looming Spanish conquest.

Things weren't much different elsewhere. For the Christians and Muslims of the Crusades, astronomical phenomena were variously interpreted as good or bad omens, and it seems that few people were willing to accept the signs in the sky as scientific phenomena only. Per Lumen Learning, the 11th-century members of the People's Crusade seemed especially primed to interpret meteors and comets as favorable omens. The appearances of meteors, auroras, a comet, and at least one lunar eclipse were all seen as signs of God's divine thumbs-up to the whole venture.

Some even went so far as to link sights in the sky with the end of the world. According to WGN, the journal of the International Meteor Organization, it could have been a tactic deployed by the church to keep everyone in line. It certainly got tied into the First Crusade when a meteor shower was spotted on April 3, 1095, and pushed Pope Urban II to declare a holy war. Perhaps part of the motivation was to score as many religious points as possible before the apocalypse came.

A few crusaders ate grass on purpose

The motivations for going on a crusade could get pretty complicated. Per the BBC, quite a few people went for religious reasons, perhaps wanting to wash away their sins in one great, grand gesture. Others, it seems, were more in it for the adventure and the possible financial gain from plundering foreign lands. And, for many, those motivations got all mixed up and produced some very strange situations indeed.

According to "The Dream and the Tomb," the Tafurs were a group of crusaders who took strict vows of poverty, to the point where they wore rough clothing, discarded many of their weapons, and ate grass and roots. Of the arms that they did wield, most seem to have been improvised farm tools or poor facsimiles of the real deal used by less fanatical crusaders. The Tafurs vocally disavowed the creature comforts enjoyed by the other people around them, leaning hard into the filth and destitution of their state and portraying themselves as "the poor people of Christ."

The Tafurs also had a reputation for ruthless war-making and plundering, to the point where they creeped out even other crusaders. They could be often relied upon to throw themselves wholeheartedly into battle, not to mention the devastation of people and settlements they found along the way. "Terror in the Old French Crusade Cycle" notes that chroniclers often called the Tafurs "depraved," expressing horror at the actions of these dramatically devoted crusaders.

Some besieged soldiers resorted to cannibalism

The Tafurs became most notorious for their reported acts of cannibalism during the siege of Antioch, where chroniclers maintained that they were among the first to consume fallen comrades and enemies alike, according to "The Dream and the Tomb." However, if conditions really were that bad, it's unlikely that they acted alone. One chronicler quoted in "The First Crusade" wrote that another siege produced hunger so terrible that crusaders were "tormented by the madness of starvation" and so resorted to consuming the remains of enemies that they had thrown into a swamp weeks before.

Soon enough, the creepy reputation of these particular crusaders began to spread beyond the walls of Antioch. When Muslim commanders asked the crusader commanders to reign in the Tafurs, many had to admit that they couldn't actually control them. It was surely an unnerving realization, to finally admit that some of the most fanatical elements under one's command were so wild and intense that they weren't really under anyone's power but their own.

One Crusader took a side quest to fight a bear

Godfrey of Bouillon is a bit of a legend. Of course, given the fact that he lived in the 11th century and the way that medieval chroniclers like to play fast and loose with the truth on occasion, it's no wonder that the real man is tied up with some wild stories. And we really do mean wild.

Godfrey was said to have been not just a noble knight and crusader but also incredibly strong. He would have had to be as such, if you believe Albert of Aachen's tale of Godfrey and the bear. As the chronicler has it, Godfrey was out and about when he encountered a peasant who had only meant to gather twigs but was in the process of being attacked by a bear. Godfrey, sword at the ready, galloped in to help but was soon torn from his own horse by the bear. Things looked pretty bad, but with his own verve and the help of a fellow knight, Godfrey was able to defeat the bear. Though pretty badly wounded, he managed to survive.

While some may be skeptical as to whether or not Godfrey actually went mano a mano with a bear, we do know that he went on to rule Jerusalem for a single year, dying in A.D 1100, per ThoughtCo. His younger brother, Baldwin, later became the first king of Jerusalem.

One crusader emperor got literally pickled

The First Crusades of the 11th century were the most "successful," at least from the European Christian perspective. Crusaders had captured the holy city of Jerusalem, but it's hard to stop something as simultaneously impassioned and nebulous as a holy war once it gets rolling. As History notes, there were many crusades after that first one, to the tune of about eight different extended campaigns in addition to various battles and other ill-considered ventures. Ultimately, as Muslim forces like those of the Saracens and the Mamluks took back more and more of the region, it became clear that the First Crusade was the high point for the Europeans.

Surely, some must have also questioned the human cost of all that war, with the many lives of combatants and innocents alike snuffed out in the name of raising the right sort of flag over Jerusalem and other cities. And it turns out that even emperors weren't so far above the fray that war could come for them in the end, too.

While traveling in 12th-century Turkey in the Third Crusade, 67-year-old Emperor Frederick Barbarossa is said to have drowned, according to "Frederick Barbarossa." Some of his heartbroken followers attempted to preserve his body in vinegar, says "Dungeon, Fire and Sword," effectively trying to pickle the deceased emperor. It didn't work all that well, and Barbarossa's remains were eventually interred in a couple of different cathedrals along the way back home.

The Children's Crusade was an odd and poorly considered venture

Perhaps one of the most pathetic episodes of the entire Crusades is the spectacle of the Children's Crusade. Actually, as History reports, there were two simultaneous crusades of young people led by two charismatic and, for our times at least, underaged boys. One was led by a highly religious 12-year-old named Stephen and, for the other group, another boy named Nicholas.

Though historians are pretty certain that both Stephen and Nicholas existed and that they attempted to jump-start some version of Crusades for Kids, the particulars of their quests for the Holy Land are pretty muddled. Some accounts say that these two adolescents drew thousands to their cause, though there's no clear way to verify those numbers. But it does appear that, by the time the groups made it to Italy and France, the whole movement disintegrated. Per National Geographic, Stephen's venture fell apart once the French king just told everyone to go home. Meanwhile, Nicholas had apparently claimed that the sea between Europe and the Middle East would part, Moses-style, and allow his group to simply walk to Jerusalem. When the Mediterranean didn't cooperate, his crusade fizzled, too. Ultimately, the Children's Crusade was never officially recognized by the Church, really creeped out adults, and was eventually dismissed as a kind of mass hysteria.

Some legends maintain that Richard the Lionheart used weaponized bees

One poet claimed that King Richard had "thirteen shippes lade with hives of bees," which he later used to defeat Muslim forces, at least according to "The Hive." During the siege of Acre, a city in what's now modern Israel, he deployed those many hives and their buzzing occupants to such great effect that the Saracens holding the city retreated.

Though there's a good chance that this is more a tall tale than a historic fact — it's worth noting that the above-quoted poem was written about two centuries after the events described supposedly happened — it illustrates the way wild stories could be used to boost various causes during the Crusades. King Richard was the legendary "Lionheart" who did indeed join the Third Crusade in 1190, per the BBC. Being a near-mythical monarch by the time the poem was written, perhaps his cunning use of bees to defeat long-term enemies such as the Saracens was more about pumping up England's image via a smart and noble king.

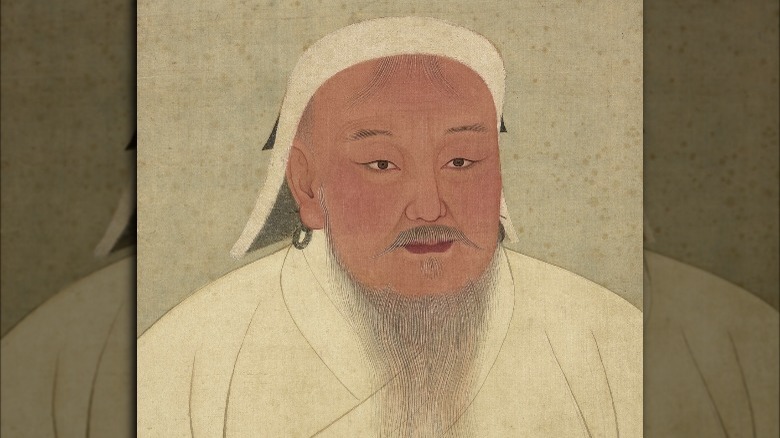

Crusaders almost teamed up with Genghis Khan

By the 13th century, it must have seemed increasingly clear that Christian crusaders were steadily losing ground. Perhaps that's why, as "God's War" notes, crusaders were increasingly interested in a non-Muslim conqueror known to many as Genghis Khan. Eventually, Khan — or the European interpretation of him — became a powerful potential ally who stood to knock down the Muslim powers and maybe would even help open the way for a Christian Jerusalem again.

It's not quite as far-fetched an idea as you might think. "Women in Mongol Iran" argues that the Mongols were fairly accepting of most religions, so long as no religious leaders stood in the way of the steadily growing Mongol Empire. Some Mongols, both individually and in groups, even began adopting Christian practices, though it's not clear how much European political leaders would have known about this.

Still, even the political tidal wave of the Mongol Empire wasn't bound to go on forever. Neither were Muslim-led forces completely helpless. It all more or less came crashing down in 1260, says History, when the Mamluk sultanate held back the Mongols in Palestine. The descendants of Genghis Khan would go no further, halting any bare hope that a Mongol-European alliance could have turned the Crusades around in the Europeans' favor.

Crusader hopes for allies led to a the legend of a mythical king

Sometimes, the crusaders' desire for a powerful foreign ally was so strong that people just collectively invented one, like a superpowered imaginary friend on a geopolitical scale. That's more or less the story of Prester John, a fabled king who was not only incredibly rich and influential but definitely wanted to help the Christian cause.

The basics of the myth, as outlined by the Journal of Medieval History, holds that Prester John was both a king and a Christian holy man. His faraway lands, variously described as being somewhere in Ethiopia or somewhere in Asia, were full of wonders and riches, including vast gold deposits and the Fountain of Youth. Some writings even claimed that his kingdom included no less than the Garden of Paradise, the original heaven on Earth from which Adam and Eve were evicted long ago. And, if only he could make contact with the crusaders, he would totally help them take back the Holy Land from non-Christians.

Only, no one ever found Prester John. Sure, there were plenty of letters and chronicles daring to outline his kingdom and way of life, but no one was able to say that they had actually met with the ruler. And, as the centuries rolled on and Europeans began to visit Africa and Asia, it soon became clear that Prester John was either very good at hiding or had never existed at all.