The Weird History Of Tetris

Tetris is a weird game. Imagine trying to explain it to someone who had never heard of it. Sounds insane, right? It was unlike anything the West had ever seen when it debuted, with its distinctly Russian aesthetic and confusing-at-first, but ultimately massively addictive game mechanics. The history of the game, believe it or not, is even stranger.

The backstory you've heard is not entirely true

The story of how Tetris happened has been told hundreds of times. Creator Alexey Pajitnov had his hobby puzzle game usurped by the greedy Communists, who sold it to America for the glory of Mother Russia and poor Pajitnov never got a penny. That's not exactly how it went down.

Pajitnov did create the game while working for the Soviet Academy of Science, but his early attempts at distribution were meant to be profitable. He formed a game development team and attempted to sell a software package of games that included Tetris, but nobody wanted the other games. So, like a lot of Steam bundles, basically.

The Soviet software regulation agency Elektronorgtechnica, or ELORG, did step in once talk of international distribution began, but the reason Pajitnov never made any money off the earliest and most popular iterations of the game is a mix of ELORG's intervention and because couldn't he couldn't successfully profit from it domestically.

Ultimately, however, the massive success of the game gained Pajitnov connections that allowed him to emigrate to the United States in 1991, and then renegotiate the terms of his ownership of the game in 1996. While that was a great year to start a ska band, it wasn't the best time to suddenly own a third-generation video game property rapidly fading in relevance. But at least he got something.

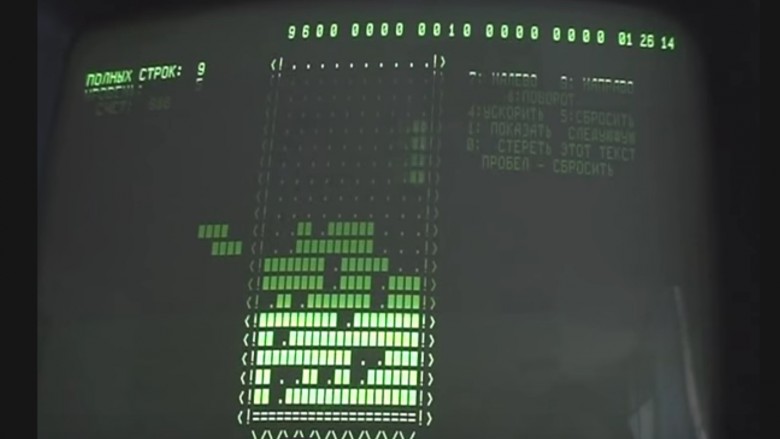

The game's design was influenced by technical limitations

In the early '80s, Pajitnov worked for the Dorodnitsyn Computing Center at the Soviet Academy of Sciences in Moscow. He had access to an Elecktronika 60, a text-only Russian clone of an older American PDP-11 business computer a decade behind the times. And you thought your office had out of date equipment.

In his spare time, he wanted to create a computer game, even if his terminal only displayed text. This and other technical limitations influenced nearly every part of the game mechanic. It originally started as a two player competitive game with five faceted pieces, like the pentominoes game he enjoyed as a kid, each manipulating pieces in square grid playing fields.

This proved wonky, so then the "well" structure and "gravity" was introduced. The pieces were then whittled down from five facets to four, because the game was too complicated to run in real-time. The "line-clearing" feature (the whole point of the game as we know it) happened because the playing field was too small, and even without mistakes, it would fill up in seconds. The whole time he coded, he used the excuse that his game was intended to "help him learn" the functionality of his office computer, elevating work slacking to truly epic proportions.

File sharing actually helped the game's success

In a time when the internet is considered a universal right, file-sharing is seen as the bane of creative types. However, in the case of Tetris, it actually helped build the increasingly addicted audience that led to the game's success. On his website, Pajitnov's colleague Vadim Garasimov, programmer of the original PC-compatible version of Tetris, had some positive things to the say about how file sharing boosted its popularity.

Pajitnov's original attempt sell the video games domestically was in a package deal with other games created by his co-workers. The package, which also included the forgettable and unpronounceable Antixonix, wasn't exactly shaking things up, so eventually they started distributing the games to friends. Everybody loves free stuff, so the game quickly spread and gained passionate, and addicted, fans. It blew up so fast, copies wound up in the United States, literally the only time you wanna hear about something from the USSR blowing up there, and game developer Spectrum Holobyte became interested in publishing it. Not the whole game package, just Tetris.

Poor Antixonix. Just wasn't your time.

Tetris literally hacks your brain, making it more addictive

A surprising amount of research has gone into figuring out what exactly makes Tetris so addictive. The truth of the matter is that it hacks your brain in multiple, kind of scary ways. The Zeigarnik Effect is an imperative function of your brain that regulates how you experience completed and uncompleted tasks. By providing a field of constantly emerging, uncompleted tasks, Tetris drives your brain to continue tidying up the playing field forever. Like Sisyphus, but if he dropped the boulder and picked up a Game Boy.

Other researchers have documented what they call "The Tetris Effect," because sometimes coming up with names is hard. This effect suggests that the fast-paced puzzles cause your brain to consume more glucose, and, as you get better, it actually tunes up the efficiency of your whole brain. Kinda like the movie Lucy, except actually based on real science.

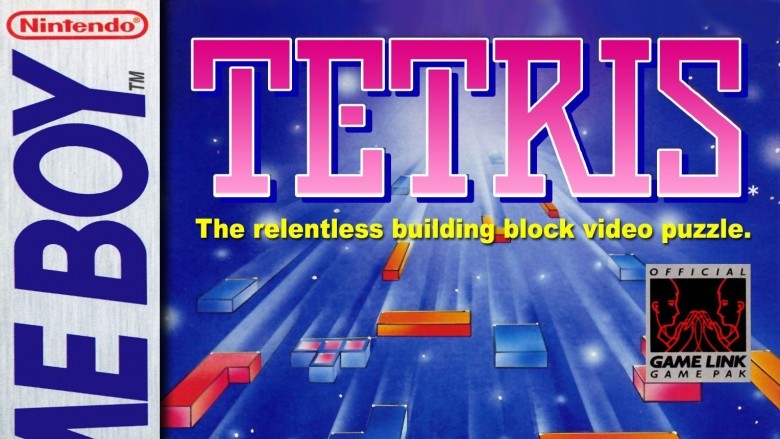

Acquiring the Game Boy rights for Tetris played out like a Russian spy movie

Video game designer Henk Rogers had a problem. He had already worked with Nintendo to license and produce the Game Boy cartridge for Tetris, and was sitting on a couple hundred thousand completed cartridges ready to go to market. However, he didn't technically have the right to license it. This wound up leading to a back-alley handshake deal with the Russian government that sounds like something out of an '80s Cold War spy movie.

"The director of ELORG [the Soviet software regulation agency], a Mr. Belikov, told me they had never given the rights to anyone," Rogers recalled. "I was in deep kimchi, because I had 200,000 cartridges at $10 a piece being manufactured in Japan, and I had put up all my in-laws property as collateral." That probably led to some awkward holiday dinners.

While in Moscow to acquire the rights, Rogers was eventually able to arrange a meeting with ELORG through his interpreter, although he technically wasn't supposed to be doing business on a tourist visa. That meeting involved being grilled by ELORG and the KGB, as well as local software moguls, and even creator Alexey Pajitnov himself. The sort of chutzpah it took to take on that gauntlet must have made an impression, because when Pajitnov emigrated to the U.S. and reacquired rights to the game, he actually formed The Tetris Company with Rogers.

The Tetris Company spends most of their time shutting down unlicensed Tetris clones on various platforms, because after being grilled by the KGB, you wanna make sure anyone else making a Tetris-like game earns the right to.

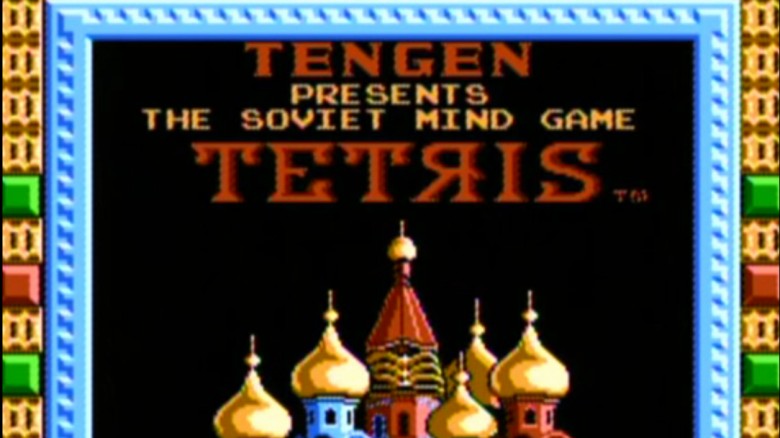

The fight over the NES version was the culmination of a bootleg war

The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was the first video game system with built-in digital rights management to discourage third-party development. Nintendo's motivation was that they wanted to avoid the surge of poor quality games that brought on the infamous Video Game Crash of 1983.

Insert Atari, the company largely considered responsible for that crash. Or rather, Atari wanted to be able to insert the cartridges it produced into the NES, and did not give a flip about Nintendo's restrictions. This led to a long-time battle that involved Atari tricking the patent office to get access to schematics of Nintendo's lockout chip. Producing unlicensed games through a subsidiary company called Tengen, Atari was able to get some games on the market. But then it wanted Tetris, too, and things got way too real.

In the end, both wound up losing out in some ways. Nintendo successfully got Tengen's games banned from retailers, but the exposure brought Federal Trade Commission anti-monopoly investigations against Nintendo, which forcing the company to loosen its licensing restrictions. Another outcome of the case was the ruling that reverse-engineering electronic products was protected by law, which changed the face of tech forever. It was also a sign of things to come for Nintendo, who soon had to deal with Game Genie getting all up in its code.

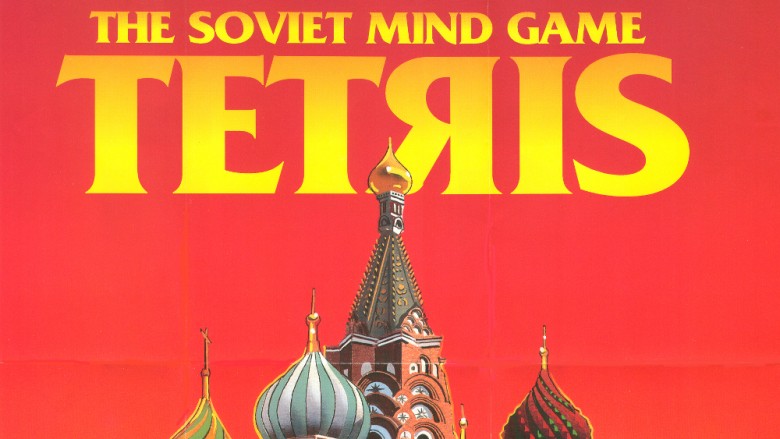

Pajitnov was embarrassed by the Russian kitsch aesthetics of the American version of Tetris

America had a very strange fascination with Russia all through the late 20th century, but the love/hate balance really peaked in the '80s, with Red Dawn, Rocky IV, and Star Wars (that Reagan laser space shield, not the movie). It seemed to lend a sort of passive-aggressiveness to the approach of localized Russian products, and Tetris was no exception. Minarets, Russian folk music, Hopak dancers cheering you on in game intermissions. It's a puzzle game — none of this was actually necessary. And creator Pajitnov found it more than a little embarrassing.

"I found all these matryoshka dolls and churches a bit tacky, but they helped sales," Pajitnov remarked. "It was very embarrassing for me: when kids of the world hear this music they start screaming 'Tetris! Tetris!' It's not very good for Russian culture."

To make matters worse, that "backwards R" Cyrillic letter you see in various logos of the game, ostensibly giving it an authentic Russian vibe, actually throws off the pronunciation. It's actually pronounced "ya." Tet-ya-is?

Tetris inspired a ton of bonkers spin-offs

If there's any indication of how hard it is to explain exactly what made Tetris popular, it's the completely ridiculous array of spin-off games it inspired. There was the genuine classic Dr. Mario, which was an iconic chocolate and peanut butter moment, sure, but then there were the rest of the games, which were more like toothpaste and orange juice.

Tetris 2/Bombliss was basically Dr. Mario without anything that made Dr. Mario enjoyable. The oddly-titled Faces ... Tris III was a Cronenbergian face-building game that was likely only purchased by serial killers. Hatris was Tetris, but with hats. Welltris was a migraine-inducing top-down view of the blocks. Wordtris was a more hateful version of Scrabble. You get the idea.

They're planning a movie trilogy based on Tetris

What in the world could a trilogy of Tetris movies be about? As of early 2017, nobody but Mortal Kombat director Larry Kasanoff and the crew of the "Untitled Tetris Sci-Fi Project" knows, and it seems like that's what they would prefer.

Speaking to Empire, Kasanoff quipped, "We're not gonna have blocks with feet running around in the movie." So we don't have that to worry about.

"We want it to be a big surprise, but it's a big science-fiction movie. I guarantee it's not what you think. Nobody has come remotely close to figuring out what we're doing."

At this point, it seems like all we can hope for is that they do.

Pajitnov still makes games, some you may have heard of

After forming The Tetris Company in 1996 and finally being in control of his own destiny, Alexey continued producing games, including Hexic in 2005 and 2013's Marbly. If you ever owned an Xbox 360, you technically owned Hexic, whether you knew it or not.

The charmingly old-school color-matching game came preloaded on Xbox 360s, likely sitting there unloved while you were playing your fancy Silent Duties and Call of the Hills and whatnot. Considering Tetris did gangbusters when it was bundled with the original Game Boy, helping to sell approximately a zillion copies of the handheld, it made sense for Microsoft to include some of that Pajitnov magic, free-of-charge. But then again, it also came bundled with Microsoft's Zune. What's a Zune? Exactly.