The Messed Up History Of Thanksgiving

For many people in the United States, Thanksgiving is an occasion for either heartwarming family reunions complete with a delicious, gut-busting meal or a pretty good gut-busting meal with a smattering of family arguments mixed in, too. Perhaps, growing up, some even came across tales of the very first Thanksgiving ever, maybe related by a relative or an elementary school teacher.

That story typically centers on the 17th century separatist Puritans known as Pilgrims, who left Europe to establish a colony in Plymouth, Massachusetts. The Pilgrims experienced an exceedingly difficult first year but, with the help of some friendly Native Americans, they were able to make it through and hold a harvest feast with their new Native buddies.

Of course, as any observant student of history can tell you, the legend glosses over quite a few important details. Meanwhile, the real story is far more complicated. Indeed, a closer look at the reality of the Pilgrims' situation in Plymouth and their relationship with the Native American tribes like the nearby Wampanoag reveals a much darker side to the modern American holiday. Here's the messed up history lying beneath the rosy story of Thanksgiving.

The first Thanksgiving story is tinged with propaganda

Because, as History notes, both earlier European settlers and Native Americans had held "thanksgiving" observances on many different occasions, practically no one at the Plymouth settlement would have considered the meal of 1621 a "first" thanksgiving. It was still a pretty big deal, though, given that the settlers had just completed a successful harvest after an exceptionally tough first year that left many of the Pilgrims dead. Their three-day celebration was meant to acknowledge the relief of that harvest. It was also indeed attended by members of the Wampanoag tribe, including the sachem (effectively, the local chief) whom the settlers called Massasoit (but who was more accurately named Ousamequin). Still, it wasn't really the "first" of anything, as far as any of the attendees seem to have been concerned.

According to The New York Times, it wasn't until around 1830 that Americans began building the myth of a seminal "first Thanksgiving" that formed a cornerstone of American culture and history. Instead of semi-mythical American ancestors, it was actually New Englanders who, after doing some historic digging of their own, concluded that the 1621 feasting at Plymouth lined up pretty nicely with their local Thanksgiving celebrations. And, per History, it didn't really get going until later in the century, when 1850s news writer Sarah Josepha Hale started a campaign to take Thanksgiving beyond its regional beginnings and make it a nationwide observance to encourage a cohesive American identity.

Many thanksgivings held Pilgrim-style could be kind of grim

For the Pilgrims, a "thanksgiving" wasn't necessarily an occasion to get together for a raucous feast and family arguments. That would have surely too readily recalled the extravagances of 17th century England, where the post-Cromwell Restoration period was busy catching up on all of the hedonism it had skipped while the Puritans were temporarily in charge. And, having moved across an ocean to establish their own little settlement of sober-minded religious folks, they could have none of that.

Instead, as Plimoth Patuxet points out, the true-blue thanksgivings celebrated by many Pilgrim settlers were often much more staid affairs. These observances often involved plenty of prayer and humbling oneself before God as a way of displaying their gratitude for a successful harvest. For the already frequent churchgoers in the colony, it meant even more time spent in strict and sober religious observance.

That said, it's not as if the Pilgrims didn't know how to get down, at least in their own way. According to History, the so-called "first Thanksgiving" of 1621 did include hearty meals and games, along with military exercises presumably intended to not just train the settlement's defenders, but also perhaps to display their defensive power.

Thanksgiving isn't just a European tradition

The most myth-heavy depictions of Thanksgiving often show a feast hosted by Plymouth's European settlers, with the local Native Americans attending and observing the proceedings as if they were a novel concept for local tribes. But the truth is that history has often glossed over Native peoples' own traditions of paying respect to nature and to deities for providing the resources necessary to live. In many ways, Thanksgiving was arguably just as much as Native tradition as it was that of the colonizers.

Speaking to The Christian Science Monitor, Linda Coombs, the associate director of the Wampanoag program at Plimoth Plantation, made this historical fact pretty clear, saying that "thanksgiving" was an everyday part of life for the local Wampanoag people then and now. "Every time anybody went hunting or fishing or picked a plant," she said, "they would offer a prayer or acknowledgement."

Whether or not the two groups of people understood that they were practicing pretty similar beliefs isn't entirely clear. The Wampanoag and the Pilgrim colonists often had a difficult time communicating, given that they spoke very different languages. And, by the time that members of both groups stood a reasonable chance of speaking to one another, the complex and growing tensions between them had further widened the gap between their cultures.

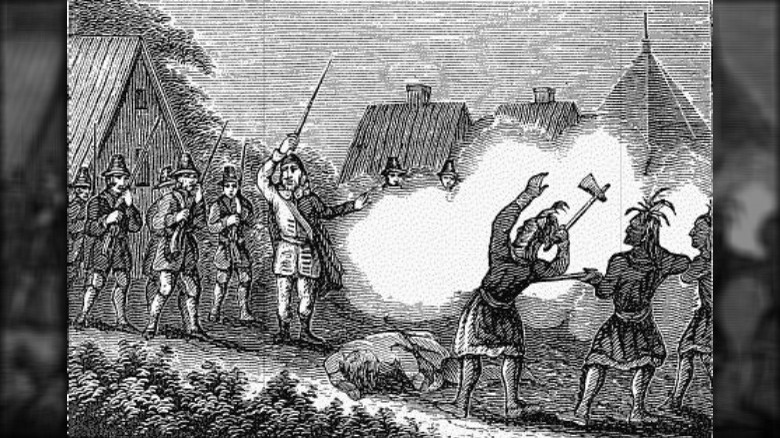

Thanksgiving is linked to the massacres of Native Americans

Many of the more simplified accounts of the 1621 thanksgiving feast note that it was held in celebration of a successful harvest and brighter prospect for the settlement of Plymouth and its inhabitants. And that is certainly true, especially when you consult accounts from that time. For instance, in 1621, colonist Edward Winslow wrote that "Our harvest being gotten in, our Governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a more special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labors" (via Mayflower History).

Yet, there is a much darker side to the Thanksgiving tradition as it was practiced by the colonists. According to The New York Times, some of the earlier records of thanksgiving observances in North America show that they were sometimes held after successful raids into tribal territory. Those raids could leave communities in shambles, with supplies decimated and people killed by attackers. One 1637 massacre against the Pequot people was marked afterward by days of thanksgiving in local colonies then established in Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay, though again it's important to note that these thanksgivings, while surely horrifying to many modern readers, aren't necessarily linked to the 1621 celebration that's been pinned as the "first Thanksgiving."

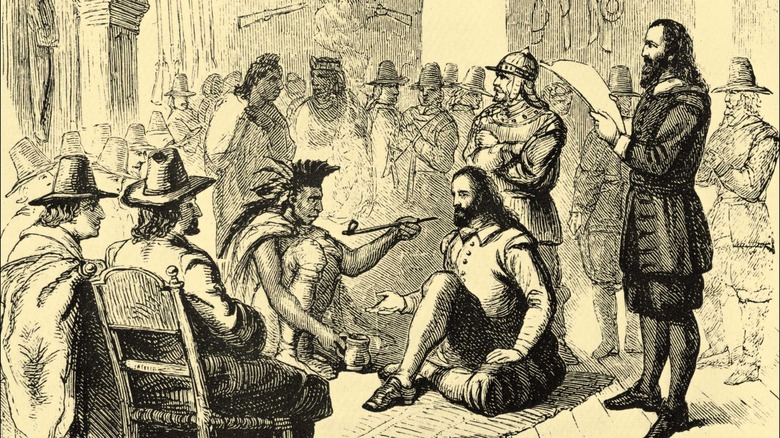

Tense and complicated tribal politics were at the heart of early Thanksgivings

As The New York Times notes, there's no evidence that the Wampanoag people were formally invited to the 1621 thanksgiving celebration. Instead, it appears as if they were traveling around checking in on their lands, their allies, and, this time around, the struggling settlers who had appeared about a year earlier on the site of an abandoned Pequot village.

It's possible that the Wampanoag were more focused on the political aspects of their visit than the warm and fuzzy notion of breaking bread with the Pilgrims. According to The Atlantic, Native people in the area had already established a complex political system well before the colonists arrived. And previous European visitors, who had often attacked and betrayed tribes, had made the Wampanoag and their current leader, Ousamequin, wary of new settlers. A 1614 visit by Captain Thomas Hunt apparently started off with peaceful intentions, but ended with bloodshed and kidnap of native people, including a man named Tisquantum who would later become a key figure.

Yet, previous visitors had proven to also be potentially valuable trading partners, which could help Ousamequin and his supporters as they struggled with internal conflicts within their tribe. It was, in short, a complicated situation that didn't fit with picture book simplicity.

The Pilgrims didn't just want religious freedom - they wanted a theocracy

Part of the Thanksgiving myth is the claim that Pilgrims only wanted to freely practice their religion but were so persecuted by close-minded traditionalists that they had to flee across an ocean to find the peace to live as they wanted. It fits in well with an overarching American narrative that hinges on personal liberty and religious freedom, though it would be well over a century until the ink had dried on the Declaration of Independence.

But the Pilgrims had already arguably experienced that religious tolerance while settled in the Netherlands, says Smithsonian Magazine. Groups of separatist Puritans had made the move there from England in the first years of the 17th century. They moved when the social and economic trends of the region changed to such a point that they felt it was time to move on.

It's fair to say that the Puritans' move to North America was part of a larger plan to set up a much more controlling religious theocracy, according to Politico. In the early days of settlements like Plymouth, leaders attempted to create a world where everyone had to live by the same moral and religious rules. Per History, dissenters like Anne Hutchinson were reviled and banished, while non-Puritan Quakers like Mary Dyer even faced the death penalty (via Britannica). It wasn't until the rigid Pilgrim morality began to fade that something approaching religious freedom began to infiltrate the colonies.

Disease pushed tribal leaders to seek alliances with European settlers

Plymouth was clear to settle in large part because its previous inhabitants had been decimated by European diseases. In fact, it's clear that one of the most devastating consequences of European settlement in North America wasn't war or cultural domination, at least not at first. It was, instead, waves of bacteria and viruses that, upon meeting the unacclimated immune systems of many Native Americans, completely devastated their numbers.

According to CNN, it didn't start with the Pilgrims. Early explorers like John Smith and his associates brought unspecified diseases that nevertheless killed many tribal members. It grew to such an extent that great swathes of land went seemingly unclaimed, at least according to a charter issued by England and Scotland's King James that referred to "a wonderful plague" that had visited Virginia and "that had led to the utter Destruction, Devastation, and Depopulation of that whole territory." Convenient for colonists who were looking for an inroad into the "New World," but terribly destabilizing for the Native American people who were left behind in the wake of the epidemics.

Smithsonian Magazine notes that, because the Wampanoag tribe was so weakened by foreign disease, they were in danger of being overtaken by rival tribes. That's likely why their leader, Ousamequin, started making diplomatic overtures to the English Pilgrims, seeking an alliance that could shore up his power and ensure the future of his remaining people.

Squanto has a complicated role in the Thanksgiving story

Central to the tale of the First Thanksgiving is a man named Squanto. As Smithsonian Magazine relates, he's often depicted as a "friendly Indian" who suddenly shows up, speaking in English and willing to teach the Pilgrims how to plant native crops and survive in the new-to-them lands of Massachusetts. However, many textbooks and histories gloss over the complexities of Squanto's role in the colonial situation. Neither do they always address the dark reality of just how Squanto became so well-versed in English or why he didn't live with his own people instead of hanging around the Pilgrims.

Actually named Tisquantum, the Patuxet man called Squanto was kidnapped and sold into slavery in Europe by an English sailor named Thomas Hunt. Hunt captured more than 20 Native people in the region, irrevocably damaging the trust of numerous tribes who had previously been at least cautiously accepting of many European visitors.

According to ThoughtCo, Tisquantum was sold somewhere near Malaga, Spain in 1614. A group of friars helped to free him, whereupon he traveled to England, then made it to Newfoundland, Canada by 1617. When he finally made it back to Plymouth in 1619, much of his tribe had vanished, being utterly devastated by diseases brought over from Europe. The rest of his life was lived in an uneasy balance between the Europeans and other Native tribes, providing translating and diplomatic services until his death in late 1622.

War showed how relationships had degraded after that thanksgiving

Though contemporary records indicate that the thanksgiving feast of 1621 went pretty well, it was likely clear to everyone that the peace between Native tribes and settlers was tenuous at best. And, as time went on, it became evident that violence was all too ready to break out.

Though it happened over 50 years after the "First Thanksgiving," a deadly conflict known as King Philip's War was inextricably linked to the repercussions of those tense, uneven relationships. As the New Yorker notes, it stems back to the line of Wampanoag sachem Ousamequin, often called "Massasoit" in the Pilgrim's accounts. Though Ousamequin had to deal with the encroachment of European settlers and their diseases destabilizing his own people, it only got worse for his successor. His son Pometacom, who was often called "Metacom" or "King Philip" by European sources, saw his own people further decimated by war and disease, while the colonists had grown to twice the natives' number — and were also blithely taking their land.

Even a powerful man like Pometacom couldn't escape the tragedy, History reports. His elder brother, Wamsutta, had originally been Ousamequin's successor. But Wamsutta had been captured by the English in 1662. They claimed he had been plotting war and, during questioning, Wamsutta died. A series of deaths and conflicts on both sides eventually lead to "King Philip's War," which lasted from 1675 to 1676 and resulted in Pometacom's death and further retribution against Native Americans.

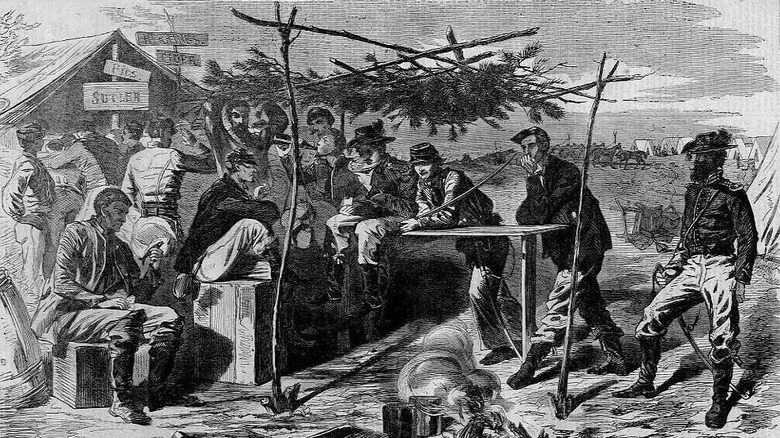

Thanksgiving was used as propaganda during the Civil War

Though it was a regional New England holiday for quite some time, the movement to make Thanksgiving a national holiday didn't get underway until the United States was wracked by the American Civil War. Per History, the first official nationwide Thanksgiving wasn't declared until October 3, 1863, in the wake of a successful Union Army victory at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The first observance was to be held on November 26 of that year.

Yet, it still didn't quite get underway, perhaps because previous Founding Fathers, like Thomas Jefferson, were wary of making such an overtly religious observance like a thanksgiving part of what was supposed to be a nation that didn't dictate its subjects' spirituality. Regardless, Abraham Lincoln, perhaps wanting to bolster support for the Union cause against the Confederacy, made a speech that referenced the need to proclaim "Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens" (via The Washington Post).

Lincoln was also likely influenced by the work of writer Sarah Josepha Hale, whose advocacy for the holiday earned her the moniker, the "Mother of Thanksgiving," according to History. She, too, wanted to use a rather mythologized version of the Thanksgiving tale to bring together the war-torn nation.

The Thanksgiving story was used to further colonize 19th century Native Americans

The course of history wasn't especially kind to Native Americans throughout the United States, even centuries after the diseases and wars between tribes and early European settlers. And this was more than tangentially linked to another set of wars in 19th century America, often referred to as the "Indian Wars." According to History, these referred to a number of conflicts and battles across the nation, from the Seminole Wars of Florida to the battles fought by Plains tribes like the infamous Battle of the Little Bighorn in the 1876 Montana Territory. Then, there were the massacres, too, from Colorado's Sand Creek Massacre to the Wounded Knee Massacre, in which Native Americans were killed by U.S. forces.

So, what does this have to do with Thanksgiving? In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, author David J. Silverman notes that increasing American interest in the holiday coincided with the end of the 19th century Indian Wars. He argues that this was a good opportunity for many Americans to gloss over the violent history of their nation with a heartwarming story of Native Americans and Pilgrims getting chummy over a dinner table. Not only that, but it was a way to include a sanitized, less dangerous facsimile of "Indians" in the founding myth of the country.