The Crazy True Story Of The British MP Who Faked His Own Death

Ambitious British politician John Stonehouse was in the United States, supposedly on business, when he went missing. He had left England without telling members of his party, forcing the work for his constituency to be taken over by other members of Parliament at short notice. The assumption was that he would be disciplined by the party on return — but on November 20, 1974, his clothes were discovered abandoned on Miami Beach. Stonehouse was gone.

Most, including his wife Barbara Stonehouse, believed that he had drowned while swimming in the ocean. Others believed he had died by suicide, due to the pressure of his businesses. The mysterious nature of his disappearance led the public and friends and colleagues alike to theorize that there was more to the story. According to an interview with the Guardian, Stonehouse's parliamentary private secretary and fellow Labour MP William Molloy believed that Stonehouse had been murdered by his political adversaries. "John Stonehouse had political enemies not confined to the shores of this land. They stretched right through to Africa, India, and Bangladesh," Molloy stated. He later added, "it is quite on the cards that he has been destroyed by the Mafia."

The truth was even stranger. John Stonehouse who, according to BBC reports from the time, many believed was on track to become prime minister in the future, had faked his own death. Here's his crazy true story.

Who was John Stonehouse?

John Stonehouse was the Labour MP for the constituency Walsall North, junior minister at the Aviation Ministry, and at one time postmaster general. Some thought that Stonehouse might go on to be the leader of the Labour Party– and Stonehouse was certainly among them. According to the Independent, his stated goal was to first become a millionaire and then prime minister.

Stonehouse was also vice-chairman of the Movement for Colonial Freedom, a campaign that worked to free Britain's colonies from Britain's influence (via University of London archives.) He worked extensively for independence for Bangladesh and was even made a Bangledeshi citizen due to his work.

Stonehouse was also the president of the London Co-operative Members' Organization, which he described in a speech to the House of Commons as, "a great ideal for me from an early age. Co-operation was almost a religion for me. It was not only a way of running a business, but a way of living from which selfishness, greed, and exploitation were to be completely excluded."

"Despite the fact that he got himself the name of being a whizz kid with so many directorships in different organizations," fellow Labour MP William Molloy assured the Guardian after Stonehouse's disappearance, "the driving force behind John Stonehouse was always based on this. Whatever he indulged in, its primary object was to further the cause of democracy and uplift the poverty stricken areas like Pakistan and Bangladesh."

How did John Stonehouse fake his own death?

Following his disappearance in Florida in November 1974, John Stonehouse resurfaced in Australia, going by more than one new alias.

Earlier in the year, Stonehouse used his position as an MP to visit the widow of a constituent named Donald Clive Mildoon. Under the guise of giving her his condolences on the death of her husband, which he claimed he was "shocked" to read about, and interviewing her for information about her life that would help him in passing a motion to help single parents, he asked extensive questions about the life of Mildoon. The two talked for close to an hour, according to Elsie Mildoon. He used the information she gave him to assume her dead husband's identity.

In an interview with ATV Today, filmed just days after Stonehouse had been arrested in Australia using the name "Clive Mildoon," Elsie Mildoon stated that the family was "absolutely shattered ... we thought he was a perfect gentleman, and I was quite proud to think he was so interested in us and came to help us if we needed help."

This was not the only name that Stonehouse went by during his escape. Among others, according to the BBC, he also used a passport with the name J.D. Norman.

John Brady, chairman of the Walsall Labour Party, described this behavior as showing Stonehouse's planned intention to perform a "disappearing act." When asked for a statement by ATV Today about the involvement of deceased constituents, he described it as "nasty, very nasty."

Why would John Stonehouse want to disappear?

John Stonehouse was "overwhelmed by debt" and failure, noted author Nigel West. At the time of his disappearance, Stonehouse had debts amounting to over 800,000 pounds. Even by his own admission, he was losing it. He was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying, "I felt I was already drowning in a turbulent sea of debts."

Stonehouse was involved with multiple business ventures outside of politics, but according to the Independent, the one which had done the most damage to his finances was an attempt to set up an investment bank in Bangladesh. The Associated Press reported that Stonehouse made statements to the police saying that after the bank began to struggle he had received multiple blackmail attempts. Simultaneously, an investigation by the Department of Trade was ongoing, trying to determine where funds raised for Bangladeshi flood relief had gone.

A charity that Stonehouse was involved with became a source of public interest while he was still missing, due to reports that there were "serious inconsistencies" with the numbers -– at least 600,000 pounds missing. His wife Barbara Stonehouse insisted to the Guardian that there was no investigation into the Bangladesh Relief Fund at all and that "my husband is dead and he cannot answer back."

Before he went missing in Florida, John Stonehouse also took out a life insurance policy on himself, worth 170,000 pounds.

Who was Sheila Buckley?

There was one person who knew for certain that John Stonehouse was still alive and where he was: his 29-year-old former secretary and girlfriend, Sheila Buckley.

As noted by a report in Birmingham Live, Buckley was also his partner in business. Stonehouse made her a director of multiple companies that he was in charge of. Despite this, many believed that she wasn't aware of the extent of the potential consequences of Stonehouse's activities, or her involvement in them. A British diplomat quoted in the Guardian would describe her as, "remarkably attractive and seemingly composed but she is really a rather silly person who has been brought to her present situation by infatuation with Mr. Stonehouse."

Although Stonehouse attempted to abandon his former life, including his wife and child almost entirely, he didn't leave Buckley behind. While Barbara Stonehouse defended her husband of more than two decades to the press during his disappearance, according to the New York Times, Buckley reportedly continued to have secret meetings with Stonehouse after he disappeared.

Mistaken Identity leads to arrest

About a month after his disappearance, John Stonehouse was arrested in Australia — under the alias Clive Mildoon. He had been under surveillance for a couple of weeks, reported the BBC, with officials believing he was someone else. At the time, they didn't realize they had found the missing MP. They thought they had caught Lord Lucan.

In November of 1974, the same month that Stonehouse's clothes were discovered on the beach, John Bingham, seventh earl of Lucan, disappeared — but under very different circumstances. According to BBC reports, Sandra Rivett, the nanny to Lord Lucan's children, was murdered and his wife, Lady Lucan, was violently attacked but managed to escape. Shortly after, Lord Lucan's blood-soaked car was discovered in Newhaven. Although Lord Lucan sent numerous letters to friends stating that it was all "a traumatic night of unbelievable coincidence," Lady Lucan identified him as the perpetrator at an inquest.

Interpol believed that Lord Lucan had fled to Australia. According to the Independent, authorities were informed of "a handsome, well-spoken but furtive Englishman who was shuttling large amounts of money into a bank account from abroad."

On Christmas Eve, detectives arrested this man, confident that they had found Lord Lucan — but it was John Stonehouse. The real Lord Lucan was declared dead in 2016, enabling his son to take over for his father in the House of Lords — but living or dead, he was never found.

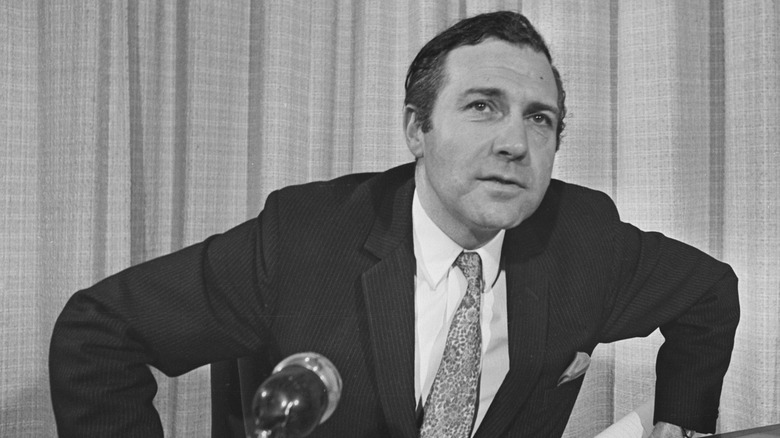

John Stonehouse goes on trial

After John Stonehouse was discovered, he was arrested and did everything he could to remain in Australia to avoid extradition to the United Kingdom, reported The Independent. In Australia, Stonehouse received bail, but he was facing charges of theft, forgery, and fraud in the U.K. At a press conference in Melbourne, he described the charges as "ludicrous" and asserted that "what they're really alleging is that I stole from myself ... The company which they say I took money from is a company that is almost 100% owned by myself."

According to the Associated Press, Stonehouse arrived for his hearing in Melbourne shortly after his capture "looking calm and relaxed." He refused to answer questions from journalists about whether or not he had entered Australia illegally. In another press conference (via Associated Press) while Stonehouse was awaiting possible extradition, he described the charges as "trumped up." Stonehouse felt that he was being persecuted and claimed that the authorities' true motivations were "sinister," stating that "Scotland Yard are engaged in a Vendetta against me."

Only three days after Stonehouse's arrest in Australia, reporter Bob Warman had asked Walsall Labour Party Chairman John Brady what he would do if Stonehouse refused to resign (Stonehouse still held his MP seat during the scandal), to which Brady replied that he would "Ask the party to support me in saying to John: 'Resign. Do the honorable thing and resign.'"

It took six months, but eventually he was forced back to the U.K., where, according to the Guardian, he was initially sent to Brixton Prison. As predicted, Stonehouse refused to resign as MP.

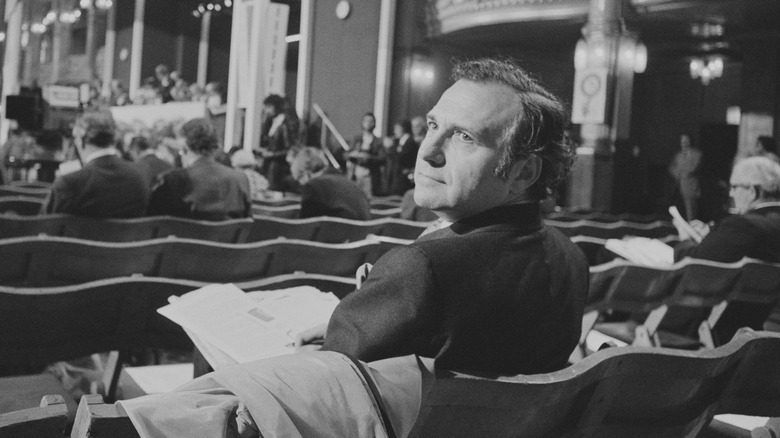

Death of an idealist

Released on bail from Brixton Prison, John Stonehouse made a speech to the House of Commons, telling his side of the story, in October 1975 (via The Guardian). "I suffered a complete mental breakdown, analysed by an eminent Australian psychiatrist as psychiatric suicide," he stated. "I assumed a new parallel personality that took over from me..."

Stonehouse referred to himself in the third person when talking about the past throughout the speech, emphasizing the idea that he had completely separated from his former political self. He explained that his work for African independence, self determination of East Pakistan, and recognition of an independent sovereign Bangladesh, which he had once been zealously passionate about, had left him disillusioned. He described this as "the death of an idealist."

"The original man had become a burden to himself, his family, and friends. He could no longer take the strain, and had to go," Stonehouse told the House of Commons. "Hence the emergence of the parallel personality, the disappearance, and long absence during the period of recovery."

In a twist during the speech he also denied allegations that he was a spy for the Czech government.

Never charged: a Czech spy

While not widely accepted as a reason for his disappearing act, as early as the 1960s, there were rumors that John Stonehouse was a foreign agent. Then-Prime Minister Harold Wilson went so far as to deny these allegations publicly in the House of Commons. In 2010, when National Archive papers were released, these accusations were revealed to be true.

According to Josef Frolik, a Statni Bezpecnost (the secret police in Communist Czechoslovakia) defector who managed a network of informants throughout the U.K., Europe, and the Middle East, the rumors were true. Fellow Labour MP William Molloy and others, even within Czechoslovakia, dismissed the possibility, due to Stonehouse's ardent anti-Communist views, according to a report from the Guardian from the year of Stonehouse's disappearance. His wife, Barbara Stonehouse, also dismissed the allegations as "ludicrous rubbish."

MI5 was quick to clear Stonehouse, but their motivations were different than his family and colleagues. According to Downing Street papers (via The Guardian), the government was certain that Stonehouse was a spy but feared that he would make a "public fuss" if confronted.

In a private meeting in 1980, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Attorney General Michael Havers, and Home Secretary William Whitelaw came to the decision to cover up any intel pointing to the possibility that Stonehouse was a paid agent. One reason was the lack of concrete evidence to prosecute. Another was timing. Only a year before, Thatcher had revealed that royal art curator Anthony Blunt was a Soviet spy in the House of Commons, as detailed in Artnet. Stonehouse was never charged.

John Stonehouse was already a target

Josef Frolik didn't just expose John Stonehouse as a spy, he revealed how he had been recruited. According to Nigel West's book, "A to Z of Sexspionage," while Stonehouse was in Prague in 1960, he was brought in by a "homosexual honeypot." For the time period, this was a fairly standard tactic by intelligence agencies. "Queer men were thought to be untrustworthy because of their queerness," Allan Hepburn of McGill University told the BBC. "They were vulnerable to blackmail because the law offered them no protection."

A variety of scandals revealing gay men to be Soviet spies, such as royal art curator Anthony Blunt, only reinforced this perception. The Guardian's former security editor Richard-Norton Taylor and "London Spy" writer Tom Rob Smith explained, "when homosexuality was illegal, spying might have been a particularly attractive career for people used to hiding their personal -– as well as political -– proclivities. They could keep secrets, and tell lies."

MI5 banned gay people from working at the agency -– a policy that would remain in place until 1991. In the United States, Sen. Joseph McCarthy and J. Edgar Hoover targeted gay politicians and government employees and campaigned hard to link sexuality and Soviet sympathies. This was sometimes called the "lavender scare."

MI5 confronted Stonehouse with the intel they had gained from Frolik, and Stonehouse insisted that he had only had lunch with a Czech diplomat.

Political fallout

During his 1976 trial, John Stonehouse was tried for theft, forgery, and fraud. He served as his own defense in a trial that lasted just 68 days, reported The Independent. He was convicted and sentenced to seven years in prison. At this point, Stonehouse finally resigned as MP.

While members of his party had been vocal about wanting him to resign, Stonehouse stepping down as MP caused major problems for his party. According to a report in the Guardian, Stonehouse's resignation forced a pact between the Labour Party and the Liberal Party. After he resigned, the election resulted in his seat going to a member of the Conservative Party. Without the Walsall seat previously held by Stonehouse, Labour lacked a majority. A Lib-Lab pact was required to avoid then-prime minister James Callaghan from losing his position.

As detailed by the BBC, in 1979, the Labour government would lose a vote of no confidence anyway, by just one vote. This led to the election of the infamous Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher.

Release and life after prison

"It is a sad fact that John is put to cleaning out the lavatories – a job considered 'light duties' – and he carries out these tasks with his usual thoroughness no doubt," John Stonehouse's brother wrote to the then-Home Secretary Merlyn Rees, as quoted in the Independent. "I am distressed that after over 30 years of 18 hours daily toil on behalf of the Labour Party, the Government and the country, John has so little support and aid in his time of need."

According to the Associated Press, Stonehouse had three heart attacks in prison. By that time, he and his wife Barbara Stonehouse divorced. Finally, following an open heart surgery, he was released early, after serving only three years of his sentence, in 1979 — the same year that Labour lost the vote of no confidence. With a coat over his head to avoid the paparazzi, Stonehouse bolted to a waiting car.

Two years after his release, he married his former secretary and co-conspirator Sheila Buckley. The two were together for the rest of his life. "My ambition, my ideas, my appetite for power, they've gone," Stonehouse is quoted as saying in the Los Angeles Times, "Burned out. Now I have tranquility and peace — rather like living two lives."

Stonehouse would spend the rest of his life writing political thrillers. He died of one final heart attack at the age of 62.