Tragic Details About Legendary Olympians

Up on the winners podium, holding a gold, silver, or bronze medal and with the crowd roaring and cameras flashing, an Olympic athlete is loved. For that one moment in time, everything aligns and everything is perfect. Or at least that's how it appears.

But an Olympic win does not translate to a perfect past, present, or future. Professional athletes are mortal, and even if they reach the highest highs of their sport, they still have personal and professional struggles, just like the rest of us. Some take a precipitous fall into ignominy, others simply disappoint. And a few athletes defy the odds and even the gods to spread their wings and fly despite real tragedy, whether it's a result of family issues, mental health, infectious disease, or even a horrific physical attack. From the athletes who endured through hardship to those who sadly lost their lives, here are some tragic details about legendary Olympians.

The following article includes details of domestic abuse, suicide, and sexual assault.

Michael Phelps battles severe depression

He is the most-medaled Olympian in history (so far), has a gorgeous wife, three vivacious kids, is worth $55 million, and is young enough to enjoy it all — Michael Phelps appears to be living the American dream.

However, like 17.3 million other American adults, Phelps suffers from depression. According to Today, the star swimmer's depression affects his entire family. He has had bouts of alcohol abuse and in 2014 was arrested for driving under the influence. "I didn't want to be alive. I saw myself as letting so many people down. I finally realized that I can ask for help and it's OK to not be OK and for me, that's what changed my life," he told Today, noting that the message that athletes should be strong became a hindrance.

Writing for Psychology Today, Steven Ilardi describes depression one of the "most tragically misunderstood words in the English language," because it's often conflated with sadness. The differences, says Ilardi, are stark. Sadness is a response to everything from life's little mishaps to outright tragedies; it is natural but momentary. Depression, he explains, is a chemical disorder that can last months and even cause brain damage. The Mayo Clinic described depression as a long-term condition with a myriad of symptoms ranging from listlessness to physical pain to suicidal thoughts, and says that medication, psychotherapy, or both can help.

Depression is a daily battle for Phelps. Even with a loving and understanding family, he related to Today that the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic spun him into a deep low. He says that journaling, meditation, and exercising help.

If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Tonya Harding lost her legacy forever

It is hard to understate how thoroughly, almost gleefully, hated Tonya Harding was after the notorious 1994 attack on her rival Nancy Kerrigan. The two professional ice skaters were already stylistically opposed — the Believer reports that Kerrigan was gracile and "elegant" (which judges loved), while Harding was muscular and "explosive" (which judges poo-pooed). After Shane Stant, an associate of Harding's then-husband, clubbed Kerrigan across the knees, the differences boiled down to Kerrigan = victim and Harding = evil.

Let there be no doubt that Kerrigan was a victim; that she took the silver at the Lillehammer Olympics is a testament to her resilience. But Harding was ruined. Her role in the assault depends on who you believe; according to National Geographic, Gillooly said Harding was the mastermind, but Harding claimed Gillooly confessed it was his plan after the fact. The Los Angeles Times reported Harding took a plea bargain for obstruction, but was banned for life from the only job she ever knew and a legacy that was rightfully hers.

Whatever the world thinks about her, one thing is absolutely certain: Harding was the first American woman to successfully nail a triple axel, a dangerously difficult maneuver. As Olympics.com relates, in 1987, powerhouse Harding pulled it off flawlessly. Three times in the same competition, in fact. Throw in a scrappy underdog story — the poor, hunting, smoking, pool-playing, smack-talking Harding was a misfit in the upper-crusty skating world — and you had a bad-girl-done-good story for the ages.

Harding was vilified by both press and pop culture, and floundered for years trying to make a living. Her image was rehabilitated somewhat by 2017's Academy Award-winning film "I,Tonya," but she will likely never compete again.

Monica Seles was stabbed by a crazed fan

In 1993, Steffi Graf was the one to beat in the world of tennis. Monica Seles did just that, and gave every impression it was going to stay that way, until she got a knife in the back. Literally.

As History explains,19-year-old Seles was leading Magdalena Maleeva at the 1993 Citizen Cup in Hamburg, Germany. She was sitting in her chair during a changeover when Gunter Parche, a man later described by tabloids as a "deranged Steffi Graf fan," came out of the crowd and stabbed Seles from behind. Yahoo Sports explains that the knife "plunged an inch into her back, but missed vital organs and required stitches and a short hospital stay."

Until that point, Seles was the top women's tennis player in the world. As Yahoo recalls, she won her first major title at 16, nabbed three consecutive French Opens wins, three Australian Opens, two U.S. Open victories, and claimed seven of the previous nine Grand Slams. Then came Parche, and his obsessive desire for Graf to regain the No. 1 title.

Though the wound wasn't life-threatening, it changed Seles' life. Suffering from lingering pain and post-traumatic stress disorder after the attack, Seles was absent from tennis for two and a half years (in which time Graf did indeed retake her former No. 1 standing). Tennis.com reports that Parche was declared mentally unfit and did not serve prison time. Following that spectacularly lenient decision, Seles vowed never to play in Germany again. She did eventually return to the sport, and she even took the bronze at the 2000 Sydney Olympics, but she never regained her career highs.

Milkha Singh died of COVID-19

Although his name may be unfamiliar to American audiences, Milkha Singh was a sprinting legend in his native India and a three-time Olympian (1956, 1960, and 1964). Popularly known as the Flying Sikh, Singh narrowly missed medaling at those competitions, but was the first Indian to win a gold for the 400-meter race at the 1958 Commonwealth Games.

You might think that his death at 91 was, as these things go, a good run. Unfortunately, the passing of that man ESPN calls "one of India's first sports superstars" could perhaps have been prevented. On June 19, 2021, Singh died of COVID-19. The loss was not only a blow to his family and India, but one of many tragic outcomes of the country's struggle to control the pandemic.

For all their superhuman feats of derring-do, athletes can get sick like anybody else. In fact, as PhysicalEducationUpdate warns, athletes are actually more likely to get chest colds and sore throats due to a decrease in the antibody protein immunoglobulin A stemming from intense endurance exercise and interval training.

Oscar Pistorius murdered his girlfriend

The tragedies of the Oscar Pistorius case are myriad: A young woman is dead, the racial and gender politics of a nation were blown open, the physically disabled lost their star player, and a man who was an undisputed sports icon is responsible for all of it.

On February 13, 2013, South African runner Pistorius was a living legend with a spectacular story. Born with fibular hemimelia, his legs were amputated below the knee when he was 11 months old, according to Biography. Despite this, as the BBC noted in 2007, he became a world-class runner on par with able-bodied athletes. His use of prosthetic carbon fiber blades led the press to dub Pistorius Blade Runner. In fact, by the time "the fastest man on no legs" made it to the London Olympics — the first amputee to do so in track and field — he was one of the most-medaled runners on the pitch, with wins at several Paralympic Games, the World Championships in Athletics, and the African Athletics Championships. An Olympic medal eluded him, but he was clearly the darling of the Games.

On February 14, 2013, it was all destroyed when Pistorius shot dead his girlfriend, model Reeva Steenkamp, and blamed it on an imaginary Black man. Initially, as Sports Illustrated recaps, it was thought to be a terrible accident: Pistorius said that in the dark night, he mistook Steenkamp for a burglar. However, as the investigation proceeded, it was revealed that Steenkamp was shot four times through a locked bathroom door, and reports of domestic fights emerged. There was no burglar, and by making up a story about a Black robber, Pistorius tapped into South Africa's delicate racial politics and what the Guardian called "the old white fear of the swart gevaar (black peril)" Pistorius was found guilty of manslaughter, and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

If you or someone you know is dealing with domestic abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

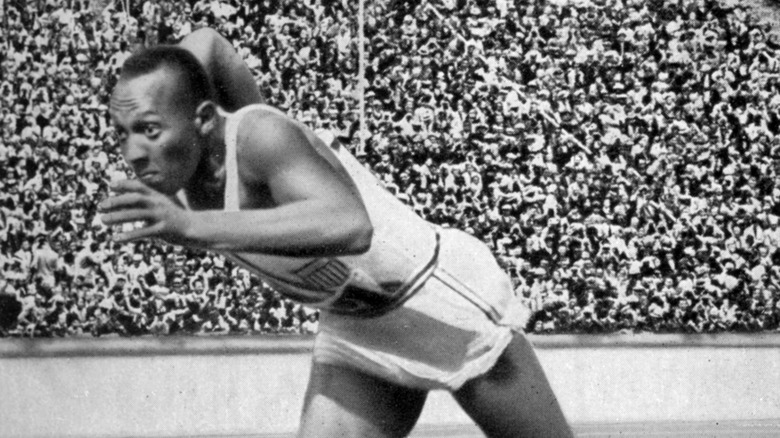

Jesse Owens could not outrun prejudice

The tragedy of Jesse Owens is two-fold. Despite winning gold medals in the 100- and 200-meter dashes, the long jump, and the 4x100 relay at the 1936 Olympiad in Berlin, when Owens returned to the USA, he had to race horses and dogs horses and dogs to make a living because Jim Crow laws made it all but impossible for a Black runner to capitalize on his success in white America, as explained by Ibram X. Kendi for Black Perspectives. Simply put, for all his legitimate greatness, Owens could not win against institutionalized racism. Presidents Roosevelt snubbed him in favor of white Olympic victors, and Kendi writes that Owens felt he had a better reception in Nazi Germany than he did in the United States. He is reported to have said "Hitler didn't snub me — it was our president who snubbed me. The president didn't even send me a telegram." In a breathtaking suckerpunch, Owens' achievements were actually co-opted into the racist views of the time, with some seeing his abilities as a result of his race rather than his individual talents.

The second tragedy is the numerous side myths that obscure the real man and unfairly lessen him. Owens was the star of the Games, but even he had limits. As Kendi observes, and despite numerous present-day examples of hyperbole and lionization that Owens "crushed" or "humiliated" Hitler, Owens' win did little to change the idea of white supremacy. Even a brief tour of history bears this out: The Jewish Library records the racial Nuremberg Laws as being in place by 1935 and they stayed on the books despite Owens's wins in 1936. Kristallnacht was in 1938, and the Holocaust continued until 1945. Also, according to History News Network, Germany won the most medals in Berlin, so the idea of Owens' victory being a humiliating defeat to the Nazis doesn't hold true.

Perhaps the biggest tragedy of Jesse Owens is that it took the world so long to see the man for what he was.

Simone Biles was sexually assaulted

The Larry Nassar scandal cut such a ghastly scythe-swipe through American sports that it is admittedly difficult, and even unfair, to single out just one of his hundreds of victims. Sports Illustrated calls Simone Biles "the most dominant gymnast ever" and she is easily the most decorated, but she was just one of the women and girls who suffered at Nassar's hands.

A little background (via CNN and Olympics.com): In 2018, Nassar, formerly a respected physician who was treating America's top female gymnasts, was convicted of sexually assault, possessing child pornography, and molesting girls and women under his care over a course two decades. Biles, along with Olympic medallists Aly Raisman, Gabby Douglas, McKayla Maroney, Jordyn Wieber, and over 150 others accused Nassar of abuse under the guise of medical treatment and under the nose of the USA Gymnastics governing body.

A blistering quote from Biles towards USA Gymnastics reads, "You had one job. You literally had one job and you couldn't protect us and it is just really sad because now every time I go to the doctor or training, I get worked on. I don't want to get worked on, but my body hurts, I'm 22 and at the end of the day that's my fifth rotation and I have to go to therapy."

Olympic-level gymnastics is a punishing sport. Bustle reports that most athletes retire in their early 20s, and that they need constant medical attention. Using that intimacy, Nassar would conduct pelvic exams and massages without gloves, sometimes even in his hotel room. That Biles and her teammates persevered to attain glory and success is a testament to their strength. Nassar was sentenced to more than 300 years in jail, but hundreds of lives have been blighted and childhoods destroyed, and no verdict can give that back.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Debi Thomas self-destructed

It was a fall no one could have predicted. Bronze medalist Debi Thomas was once one of America's best professional skaters, and the first Black woman to take a Winter Olympiad medal. The Toronto Star describes Thomas as an A-type woman who had it all: She was enrolled in college while competing, and after retiring from skating, graduated from Stanford with an engineering degree. She then attended medical school at Northwestern University, married a handsome lawyer, had a beautiful son, and became an orthopedic surgeon.

But today, Thomas lives in a mobile home, lost her medal to bankruptcy, is unemployed, twice divorced, and hasn't seen her family in years). She espouses various conspiracy theories, her medical license is expired, and she peddles gold bullion online as a way to fend off a coming financial apocalypse. What happened?

The easiest answer is that Thomas suffers from untreated bipolar disorder, a condition she contests. She moved from Illinois to the impoverished coal town of Richlands, Virginia, to start her practice, and left her husband and son in the process. In 2012, she got into an altercation involving a gun with her partner. When the police arrived, Thomas reportedly said she wanted to hurt herself. As a result of the incident, she underwent a psychological evaluation and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. She was unable to keep her medical practice going, and the bills started to add up.

In 2015, she made a reality TV appearance on an Oprah Winfrey Network show, in which she said "I did the best I could. I don't have a plan."

If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

The rises and falls of Jennifer Capriati

A bonafide prodigy of the game, Jennifer Capriati made the youngest-ever professional tennis debut in 1990, when she was just 13 and 11 months. Britannica notes that her strength lay in her power and consistency, and her "bubbly" personality positioned her to be the Mary Sue of the Women's Tennis Association. When Capriati took the gold at the 1992 Olympics, everything seemed peachy. Looking back, ESPN observes that the attention and pressure at such a young age may have been the problem.

As observed by the New York Times, Capriati was heavily promoted as a lily-white goody-goody, the all-American sweetheart of tennis. So much so, in fact, that minor infractions mutated into major catastrophes and PR disasters. Writing for AmoMama, Manuela Cardia recounts when Capriati was recovering from an injury at age 16, she was caught shoplifting and in possession of marajuana. For an athlete with such a wholesome and clean-cut image, it was a big deal. Cardia writes that "what would have been normal acting-out of a rebellious teen assumed gargantuan proportions." Britannica adds that "the pressures of professional play and her parents' divorce" also took their toll.

Olympics.com reports that Capriati rallied in 1998 with a Wimbledon win, but by 2002, her performances revealed her crippling eagerness to please but a lack of mental confidence (via the New York Times). A shoulder injury in 2004 ended her career at age the premature age of 28, sending her into a deep depression.

Since then, Capriati has stumbled. In 2010, she overdosed on pills, according to ABC News, and she stalked and attacked her boyfriend in 2013, for which she undertook 30 hours of community service and an anger-management class. Capriati was inducted into the Tennis Hall of Fame in 2012 — a definite high — but her lows are a familiar warning of "too much, too fast, too soon."

Greg Louganis: Triumph over tragedy

When diver Greg Louganis famously hit his head on the Olympic springboard in 1988, he was lucky to walk away with stitches and a concussion. That he recovered and took the gold for the event gave the press goo-goo eyes for the man's fortitude, but what most didn't know was that a head wound was chump change to the massive hit Louganis was already dealing with: He had been diagnosed as HIV positive just six months before.

"Had they known about my HIV status at the '88 Olympics in Seoul, I would have never been allowed into the country," the four-time Olympic gold medalist told ESPN. As it turned out, Louganis crashed into the safest place in all South Korea; the chlorinated water of the pool neutralized the virus in his spilled blood.

But his status was just one more secret the deeply closeted Louganis had to keep in a sports world whose homophobic machismo was, and still is, rampant. In 1988, homosexuality was a career killer (and HIV/AIDS was a killer flat-out), and like many closeted athletes, Louganis had private lows alongside very public highs.

A Newsweek article gives a harrowing account of his early life, from being born to unmarried parents to his adoption into a family headed by an alcoholic father. He endured racial slurs for his dark skin, was belittled for his dyslexia, and called "sissy" for his love of acrobatics. His teenage years were marred with drug use and a suicide attempt. In his autobiography "Breaking the Surface," Louganis recounts how he fell into a destructive relationship with a man who raped him at knifepoint. That Louganis, now in his 60s, healthy, and a beloved sports icon and gay superstar, makes it out the door every morning, to say nothing of reaching the Olympics, is medal-worthy.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

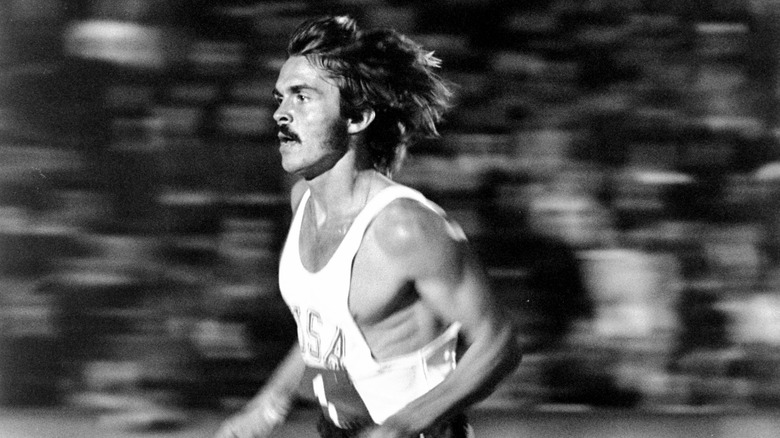

Steve Prefontaine: The danger of drunk driving

When long-distance runner Steve Prefontaine got behind the wheel with a blood-alcohol content of 0.16 percent in 1975, he was already a legend. His entry at Olympics.com records that he was the American record holder for every distance race from the 2,000 meters to 10K. But, according to Oregon Encyclopedia, the man the world knew as "Pre" lost control, hit a boulder, flipped the vehicle, and was pinned under the wreck. He survived the crash, but was asphyxiated by the weight of the car and died at the young age of 24.

It is, of course, speculation as to what other career highs Prefontaine could have reached, but the man was likely set for greatness on and off the track. With a running style Olympics.com calls "cocky," Prefontaine bucked tradition by sprinting at the start of his races and maintained strong leads. Good-looking and charismatic, he was a genuine sports hero, with "Go Pre" being a popular t-shirt logo at the time. That pop culture gravitas, says John Moriello of Sportscasting, was a power Prefontaine used to his advantage for athletes of all sorts; leveraging his fame, he worked to successfully overturn the Amateur Athletic Union prohibition of corporate sponsorships and commercial contracts that all but condemned amateur sportspeople to live and train in poverty. Moriello notes that court win may be as much a part of Prefontaine's legacy as his running.

Olympic glory slipped from his grasp at the Munich Olympics in 1972, but he was considered the frontrunner for the 1976 games, an Olympiad he would never see. The untimely death of Prefontaine sent shockwaves through the sports world, with posthumous tributes ranging from the Prefontaine Classic, an annual track and field meet held at the University of Oregon, to several films about the man.

Dawn Fraser accidentally killed her mother

Now in her 80s, Dawn Fraser is a four-time Olympic gold medalist and a legend in her native Australia. Being one of the star swimmers in Melbourne (1956), Rome (1960), and Tokyo (1964), she has a resume most would-be mermaids would give a fin for. She even gained a bit of notoriety when, during the Tokyo Olympiad, she was arrested for stealing a flag from the entrance to the Emperor's Palace. As Olympic.com reports, the international incident ended on the best possible note: The charges were dropped, the emperor gave her the flag as a gift, and there were warm fuzzies all around.

But Fraser's life wasn't all awards and accomplishments. By the time she competed in Tokyo, she had survived two rapes, had thoughts of suicide, endured domestic violence, and was reeling from the fact she had been behind the wheel in a car accident that killed her mother just eight months earlier (via Yahoo! Sport).

Complicating things further, Fraser was kept in the dark about her culpability in her mother's death. In the days after the accident, her family said her mother died of a heart attack and not the accident itself. As she related to the Sydney Morning Herald in 2004, it was not until 2001, when Fraser was writing an autobiography, that she learned the truth. At a training camp in 2019, she finally confronted the memory fully. "I burst out that I was driving the car that killed my mother," Fraser said. "Everyone burst into tears and I cried with them. It got me over some sort of hurdle. I'd just locked it up inside of me."

Fraser is now the elder statewoman of her sport in Australia, and has served in Parliament.

Betty Robinson fought her way out of a coma

According to BettyRobinson.org, a young Betty Robinson found herself missing the train to school, so she ran after it and caught up. Her biology teacher was on the same train, and recognized her remarkable running speed. With a little training, Robinson was on a boat to the Amsterdam Olympics that year. TeamUSA details how the 16-year-old ran a world-record time of 12.2 seconds in the 100-meter to win the gold. Amsterdam was the first Olympiad in which women competed in track and field, making Robinson the first female runner to medal at the Olympics. This is what she should be known for.

Instead, she may go down in history for a plane crash. As recounted by STSTWMedia, in 1931 Robinson took a ride with her cousin in his biplane. At around 2,000 feet up, the plane stalled, nosedived, and crashed. Rescuers thought Robinson, who had been severely injured with a broken arm, shattered leg, and a gash to the head, was dead. The undertaker realized that she was in a coma and hurried her to the hospital. The Evening American reported "Lying almost paralyzed on a cot, Betty Robinson today fought to win the hardest race she ever ran — a race in which the Grim Reaper was pacing her."

Robinson spent 11 weeks recuperating, much of it unconscious. Yet this is one of the great Olympic comebacks; as Wbur recounts, Robinson rehabilitated herself back into running form. She could no longer crouch into the stocks, so she trained for the 4x100 relay in the 1936 Berlin Olympiad. And when the Germans dropped the baton in mid-race, she took home her second gold.