The Most Memorable Moments From Summer Olympics History

In A.D. 393, Roman emperor Theodosius I banned the Olympic Games as a pagan festival, according to History. Few thought that they would ever resurface despite attempts to revive them. In 1896, however, the dream came true. The Olympic Games were revived after nearly 1,500 years under the careful watch of French aristocrat and sporting enthusiast Pierre de Coubertin as a festival of amateur sports. The first games in Athens were memorable and significant, coinciding with Greece's independence day and Easter Monday (via Europeana) and sending a message of unity to all those who participated.

Since that memorable day, the Olympics are a gift that keeps on giving, providing remarkable moments of athletic prowess, sportsmanship, unity, and even occasional bad behavior. Below are listed many memorable moments, from the more obvious and recent ones such as Usain Bolt and Michael Phelps to memorable but lesser-known events from games long passed.

Berlin 1936: unity through sport

The 1936 Olympics were supposed to be a testament to the supremacy of the Germanic race, and Adolf Hitler had high expectations for Germany's athletes. Because of the Nuremberg Laws and the targeting of Germany's various minorities, there was a call to boycott the games. Per Craig Chamberlain of the University of Illinois, the NAACP lobbied for the United States to withdraw, and the organization's president had even prepared a letter for one of the team's star athletes, sprinter Jesse Owens.

Owens went to the games anyway, and he won four gold medals. One of his most memorable moments, which infuriated Hitler, came after he won the long jump. Owens was behind German Luz Long and was risking elimination in the qualifying rounds. According to Owens himself (via NPR), Long gave him some technical advice that allowed him to advance to the final round, which he won. Later, though, Owens admitted that he had made that part of the story up. It is true, however, that he and Long embraced after the games were over, much to Hitler's displeasure.

Long and Owens continued their friendship until 1943, when Long was killed in World War II. In his last letter, Long asked Owens to tell his (Long's) son "how things can be between men on this earth." These final uplifting words captured the true spirit of the Olympic Games, transcending national, racial, and political boundaries that otherwise divided the world in the bloodiest conflict in human history.

Berlin 1936: battery on the ref

While Jesse Owens and Luz Long captured the spirit of the Olympics, the soccer tournament, according to FIFA, showcased some uglier, unsportsmanlike behavior. Italy was the tournament's undisputed favorite. The Azzurri had won the 1934 FIFA World Cup, and it was expected that Italy, under legendary coach Vittorio Pozzo, would steamroll the United States, whom they had defeated 7-1 in the World Cup two years earlier.

Pozzo made numerous changes from the 1934 squad, choosing a younger team of state-sponsored athletes to skirt prohibitions on professionals. In the single-elimination tournament, the Azzurri were drawn against the United States. The Americans, hoping to avoid another embarrassment, put up a dogged defense but eventually conceded a goal to Italy's star forward Annibale Frossi.

Soccer was much more physical in the 1930s, and Italy had a reputation for playing rough. The Americans learned this when Achille Piccini brutally fouled two of their players in succession and was sent off. There were no red cards at the time, so the German referee had to verbally eject him. Instead of leaving, Piccini and the other players swarmed him, restraining his arms and even covering his eyes with their hands. Incredibly, Piccini and the other guilty players stayed on, and the game continued, perhaps to avoid a political scandal due to Italy's close political relationship with the hosts. Italy went on to win the tournament, defeating Austria in the final before marching on to a second World Cup title in 1938.

Helsinki 1952: The eight record breakers

The Second World War delayed the Olympics until 1948, when London reopened the games and ruined Europe was given a reason to celebrate again. In 1952, the games moved to Helsinki, which had managed to avoid absorption into the Eastern Bloc. Because of the improvements in training, combined with the fact that no records had been broken since 1936 at the games, it gave an opportunity for new stars to achieve personal bests and shatter old records.

The Olympic record for the 1,500-meter run in 1952 belonged to Jack Lovelock of New Zealand with a time of 3:47.8. Three minutes and 45 seconds later, that record had been broken eight times. According to the International Olympic Committee, Luxembourgish athlete Joseph Barthel led the way, winning the gold with a time of 3:45.2. Incredibly, the next seven runners in the final all ran under 3:47.8, as well. In fourth place, just outside of the medal zone but faster than the previous record, was a young Roger Bannister. Although he did not win in 1952, he would be the first man ever to run a documented sub-4 minute mile, heralding a new era in middle-distance running.

Melbourne 1956: The Melbourne Bloodbath

In October 1956, Hungary sought to throw off the shackles of communism and out their Soviet-backed puppet government, but the USSR intervened militarily and suppressed the revolt. What followed was a bloody series of executions and repression. The champion Hungarian water polo team, however, according to the BBC, had been cloistered in Czechoslovakia for training and was unaware of the events.

In November, the Hungarian delegation arrived in Australia, and the team's sole English-speaker found out about the scale of the Soviet massacres from local newspapers. Immediately, many resolved to defect after the games, but before they did, they would crush the Soviets in the semifinal.

According to Hungary Today, the Hungarians decided to taunt the Russians during the match, insulting them and provoking them to violence. Small scuffles broke out throughout the game, and by the end, Russian Valentin Prokopov punched his Hungarian marker, Ervin Zádor, and made him bleed. The pro-Hungarian audience attacked the Soviet players, and the police had to be called in to clear the area. Hungary won 4-0 and advanced to the final, where it defeated Yugoslavia to take the gold. Following the game, much of the team defected, including Zádor, disgusted with the Soviet treatment of their countrymen and their own government for its collaboration with Moscow.

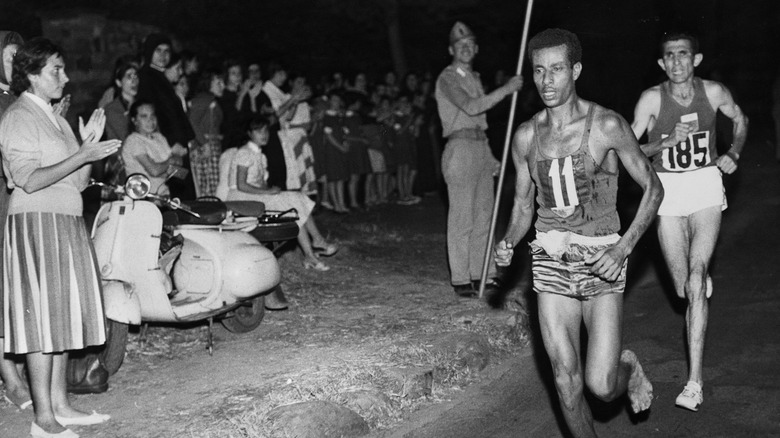

Rome 1960: Enter East Africa

In 1960, rumblings of independence were felt across Africa as new nations rose out of the European colonial states. As Africa's new nations declared independence, they began to participate in world sporting events such as the Olympics. Ethiopia led the way to what would be a first medal for a sub-Saharan African nation.

Born on a mountainous, remote plateau in the Shewa region of Ethiopia, Abebe Bikila hardly seemed like a candidate to become a world champion. His life, however, according to Sports History Weekly, took an unexpected turn when he joined the imperial guard. As part of his duties, he regularly ran long distances at more than 8,000 feet above sea level, giving him an unparalleled level of fitness that caught the attention of Swedish coach Onni Niskanen.

Bikila reached the world stage in Rome in 1960, when he qualified for the Olympic marathon. 1960 was Ethiopia's second participation in the games. The 1956 delegation came home empty-handed, and there was hope that this time, things would be different.

Per Science Daily, when Bikila arrived in Rome, he did not have a pair of shoes to run the race in. After buying some that did not fit, he opted to run barefoot instead, which was (and still is) permitted under IOC rules. In the scorching heat of the Roman summer, Bikila defeated Moroccan Rhadi Ben Abdessalem to clinch the gold, Ethiopia's only medal that year. His win made him a national hero and is credited with beginning the East African domination of distance running that continues to this day.

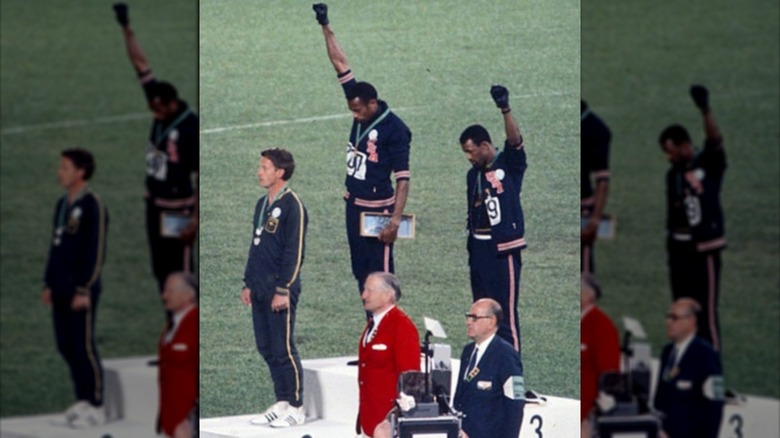

Mexico 1968: Black Power salute

USA Today notes that the 1968 games in Mexico occurred against a backdrop of tumult in the United States. Between race riots, Vietnam protests, and the Civil Rights Movement, there was the hope that Americans could put aside divisions and enjoy the games.

According to History, U.S. athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos finished first and third in the 200-meter, respectively. However, during their medal ceremony, they decided to wear black socks without shoes to symbolize the economic poverty among African Americans in the United States, in addition to black gloves. In protest of segregation and other forms of institutional racism, the two men also gave the Black Power salute by raising their black-gloved fists.

The controversial gesture drew the ire of the International Olympic Committee. Per ESPN, American IOC president Avery Brundage ordered the U.S. Olympic Committee to expel the two, or he would suspend the entire athletics team. The USOC caved over the threat, and the two men were sent home. The USOC noted, however, that Italy and Germany had not been disciplined over Roman salutes in 1936. As for Carlos and Smith, both of them defended their decisions. Smith famously said after the incident that he sought to bring attention to the hypocrisy that if he won, he was American, but if he lost, he was Black. Smith hoped to be celebrated for his achievements without discrimination.

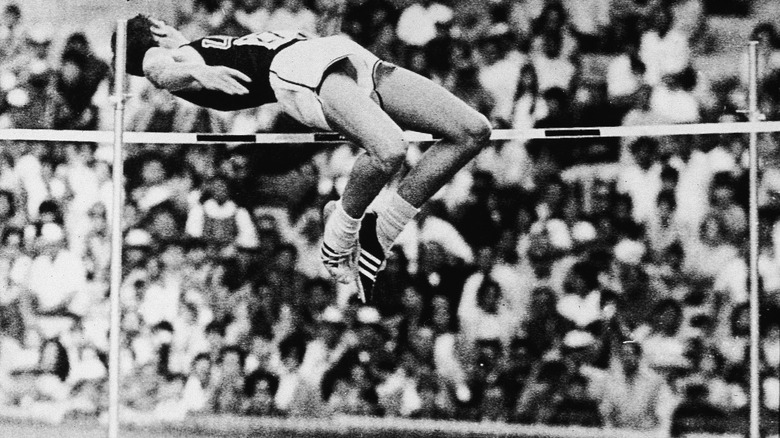

Mexico 1968: The Fosbury Flop is born

The Mexico City games featured another memorable moment that was ultimately overshadowed by the Black Power salute. Nevertheless, this particular one would change how the high jump was executed. According to the IOC, the high jump before 1968 was usually performed with a straddle jump. The athlete ran up to the bar and jumped over upright, eventually landing on his feet. Because there was little padding, landing on one's feet was crucial to avoiding injury.

For thin athletes, these types of jumps resulted in knee injuries. Dick Fosbury, a student from Oregon, changed the way the jump was executed. Instead of jumping up, he ran the last few steps along an arc before jumping and twisting his body into a supine position relative to the bar. According to Stanford, his center of mass stayed under the bar. Although, according to History, it looked to observers "like a guy falling off the back of a truck," it worked. Fosbury proved his detractors, who'd claimed his way of jumping would kill high jumpers by breaking their necks, wrong by winning the gold medal.

The Fosbury flop changed the way the high jump was executed — today, it is the principal technique. It also resulted in some changes to the high jump station, as more padding was needed to ensure that athletes had a soft landing to avoid injuring their heads and necks.

Munich 1972: The student impostor

American and Yale cross country and track star Frank Shorter was the favorite to win the 1972 Munich marathon. As he approached Munich's Olympic Stadium, victory was within sight. Before the lead pack entered the stadium, however, a man dressed in a West German uniform suddenly and unexpectedly came running in, per The Active Times. The crowd cheered at first until they realized what was happening. Before long, Shorter entered the stadium behind the new runner to a chorus of boos (which were meant for the unknown marathoner).

According to sportscaster Jim McKay, the mystery runner crossed the finish line effortlessly, too effortlessly for some. It would be expected that someone running a 26.2-mile race would be exhausted and collapse after the finish line. Instead, the imposter continued running before security intercepted him. The false marathon winner turned out to be a West German student named Norbert Sudhaus.

Munich 1972: A Cold War matchup goes down to the wire

The 1972 men's basketball final was a Cold War matchup between the undefeated United States and the Soviet Union. This game would be settled, controversially, at literally the last second of the match.

According to the LA Times, the score stood at 49-48 in the Soviets' favor, with three seconds left. The Americans were handed a lifeline of two free throws after Zurab Sakandelidze brutally fouled Doug Collins. Collins' first shot tied the game. As he was taking the second, the Soviets requested a time-out. Brazilian referee Renato Righetto, however, did not stop play. With the score now at 50-49, the Soviet staff protested the refereeing decision. Since a time-out could not be called after the free throw, they were forced to attack the American half of the court with no plan and only one second left.

Per Sports Engine, Righetto resumed play with one second on the clock, the Soviets failed to score, and the Americans celebrated. FIBA head Renato Jones, however, ordered the clock back to three seconds, when the Soviets had requested their time-out. Righetto protested but ultimately relented. Both teams returned to the court. A long pass from Ivan Edeshko to Aleksandr Belov allowed the latter to score a layup, handing the Soviets a 51-50 victory and the gold. Jones later admitted his mistake, as he had not expected the Soviets to score. To this day, the silver medals remain unclaimed, stored in an IOC vault in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Montreal 1976: A perfect 10

At the 1976 Olympics, 14-year-old Nadia Comaneci stole the spotlight and brought glory to her nation, the small Balkan country of Romania. According to CNN, Comaneci had trained her whole life, since age 6, for her Olympic moment, and she went all in from the beginning. In the opening rounds of the gymnastics competition, she shocked the world by earning the first-ever perfect 10 in Olympic history on the uneven bars and balance beam, a feat she would repeat six times that year. Her skill blew away her competitors, chief among them Soviet gymnast Nellie Kim. Although Kim also managed a perfect 10 after her Romanian opponent, she never gained the same fame.

Although Comaneci's performance turned her into an international icon and trailblazer in women's sports, her fame came at a price. According to Romanian historian Stejarel Olaru (via Balkan Insight), Nadia was monitored around the clock under the watchful eye of the Romanian Securitate, mostly for fears she would defect to a NATO country if she was allowed to leave Romania. Olaru also claimed that Nadia experienced abuse at the hands of her coach Bela Karolyi.

Nadia herself refused to comment on the allegations. She never denounced Karolyi or his training methods, and according to Olaru, she never let her negative experiences get the better of her. Comaneci eventually fled Romania to Hungary and then the United States in 1989 before the Ceausescu regime collapsed.

LA 1984: A trip or a tumble?

The 1984 3,000-meter final had three main contenders. Romanian Maricica Puica and American IAAF champion Mary Decker were the favorites. Joining the trio was 18-year-old South African-born Zola Budd, who represented Great Britain. Decker was billed as the likely winner, but some bad luck (or foul play) would end her and Budd's hopes of an Olympic gold.

In the middle of the race, Budd and Decker became entangled with each other while jockeying for position. Decker tumbled onto the infield, while Budd managed to keep going. Budd had tripped her opponent, or so it seemed. According to Page Six, the media blamed Budd for Decker's loss. The officials disqualified Budd but soon cleared her of any wrongdoing. However, she gave up the race and dropped back to seventh place, leaving Puica the gold.

With the emotion in the past, the LA Times reported that today, the consensus is that Budd was innocent. In a crowded first lane, Budd had stumbled under Decker's close pressure. In athletics, it is the athletes' responsibility to avoid interfering with those in front of them. Boxed inside lane 1, Decker had no room to move but forward. When Budd tried to move out of her way, the contact resulted in the trip that cost Decker the gold. CNN noted Decker's own inexperience with pack running, which Sports Illustrated had previously stated cost her the gold.

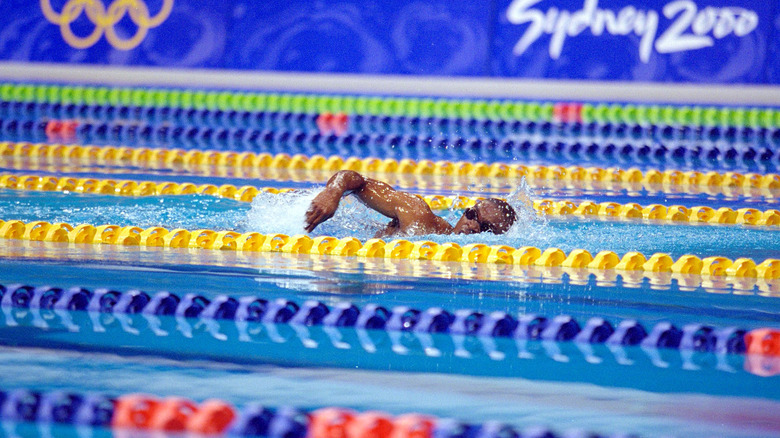

Sydney 2000: A wildcard water fiasco

Fast-forwarding to the Sydney games in 2000, this next moment is not known as a great one in sports. Rather, it was considered an embarrassment for the small African country of Equatorial Guinea and for the IOC's wildcard system.

The wildcard system was meant to give unqualified athletes from less developed countries a chance to compete in the games, stressing the importance of wide participation. In 2000, Equatorial Guinea received a berth in the 100-meter freestyle. The problem? They had no athletes. The Guinean government resorted to taking volunteers and eventually settled on 22-year old Eric Moussambani. The Guinean, however, barely knew how to swim, according to Yahoo. He trained in a hotel pool, and his arrival in Sydney was the first time he had ever seen an Olympic-sized pool.

Moussambani tried to learn quickly from watching the American delegation, while the South African coach had to give him a regulation uniform. When his time finally came, he struggled through the race, finishing in 1:52, the slowest time on record. His flailing technique in the final meters earned him the name "Eric the Eel." Incredibly, he still won, as both of his rivals were disqualified for false starts. He worked to lower his time, and he qualified for the 2004 Olympics. A visa issue, however, forced him to withdraw from the games. Eventually, the government made him Equatorial Guinea's national swim coach, and he helped raise the sport's African profile. The embarrassment in Sydney had not been in vain.

Sydney 2000: Korean unity through sport

The Korean peninsula has been divided since the Soviet Union installed Kim Il-Sung's communist regime in North Korea in 1945. Since the Korean War armistice of 1953, there have been multiple attempts at détente with hopes of eventually reunifying the peninsula. The 2000 Sydney Olympics provided an opportunity to build bridges between the two sides.

North and South Korea compete as separate countries with their own delegations, flag bearers, and anthems. In 2000, however, according to The Guardian, the two countries held a summit in Pyongyang and decided that in Sydney, the two delegations would march in the opening ceremony together in one uniform, under one flag, and with one anthem. According to ESPN, with the approval of the IOC and their respective governments, blue-clad Korean athletes mingled freely as if one nation and marched together under a white flag emblazoned with the blue outline of the Korean Peninsula.

Many Koreans interviewed that day, some of whom undoubtedly remembered the war, expressed joy at the sight. Although many believed that the moment would never be a reality in their lifetimes, the gesture contributed to hopes that the Olympics and sports in general could help heal the political divide of the 53rd Parallel.

Beijing 2008: Lightning Bolt

Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt needs little introduction these days. Before Beijing 2008, he was already making a name for himself in the athletics world when he clinched the silver in the 200-meter at the 2007 IAAF World Championships. However, he did not become a recognizable figure until he received broader public exposure on the Olympic stage.

At the 2008 games in Beijing, Bolt notched a double world record. His famous 100-meter run in 9.69 seconds earned him a world record and the nickname "Lightning Bolt." He then broke the 200-meter record, smashing the previous record of 19.52 seconds with a 19.30. As detailed by The Guardian, Bolt's celebrations and alleged showboating drew criticism and claims that he could have run even faster if he hadn't slowed down. Since then, Bolt has broken his own records several times but was forced to retire after a hamstring injury in his final race at the 2017 IAAF World Championships. He then had a short stint in Australian soccer with the Central Coast Mariners. After the soccer career didn't quite work out, he retired from all sports in 2019.

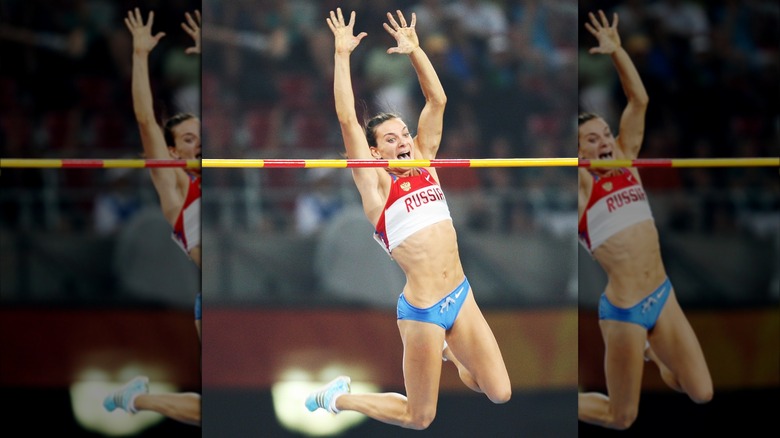

Beijing 2008: Isinbaeva (aka the female Bolt) rocks Russia

In the first decade of the 2000s, Yelena Isinbaeva was the darling of athletics and the "first lady" of the pole vault, per the IOC. The Russian pole vaulter had won the 2004 Olympic gold and set a world record of 4.91 meters. In Beijing in 2008, as Usain Bolt was lighting up the track, Isinbaeva was smashing her own records, drawing comparisons to the Jamaican sprinter and elevating the Russian's name to global recognition.

According to World Athletics, the 2008 pole vault pitted Isinbaeva against Jenn Stuczynski, the only athlete believed to be capable of defeating her. By the time the bar was set to 4.80 meters, only Isinbaeva and Stuczynski remained in the competition. Both athletes cleared the height, and the bar was moved to 4.90. Stuczynski failed to clear and was eliminated, leaving Isinbaeva to face her most difficult opponent — herself. Needing two jumps to break her now-5.04-meter record, Isinbaeva cleared 4.90, and then on her final jump, she set her 24th record by vaulting 5.05 meters. Isinbaeva's incredible exploits earned her athlete of the year in 2008. Joining her on the stage was Usain Bolt, who was the award's male counterpart. Together, they formed an unstoppable duo whose records continue to stand nearly 15 years later.

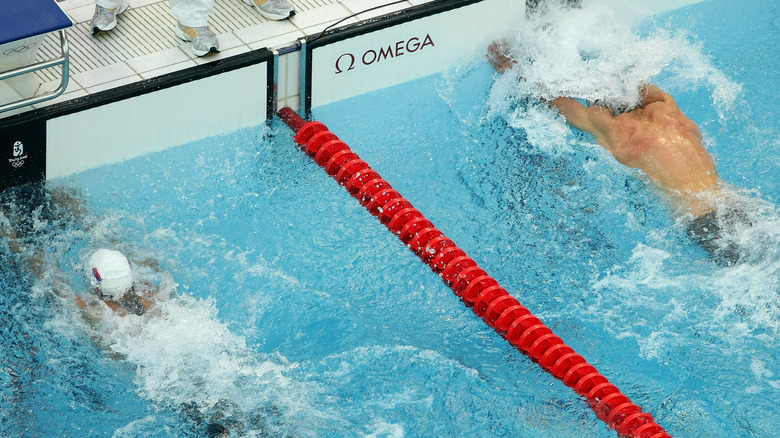

Beijing 2008: Robbed by the touchpad?

In the pool, Beijing 2008 featured the man who can rightfully be called America's greatest swimmer. That year, Michael Phelps won eight gold medals, breaking the previous seven-medal record held by fellow American Mark Spitz. Phelps won his seventh gold medal in the 100-meter butterfly. At least, this is what the official results say. His opponent at the time, however, claims otherwise. Serbian-American swimmer Milorad Cavic told The Ringer that he had touched the wall before Phelps and therefore should have been declared the winner. If this is true, the fault would lie with the touchpad. Cavic's touch should have triggered it, but it is possible that his touch was not forceful enough to stop the clock. Instead, Phelps' touchpad stopped the clock less than 1/100th of a second before the Serb's pad, handing him the medal. Watching the video, it is difficult to tell what happened, but Vice published the photo-finish, allowing viewers to judge for themselves.

Cavic has never disputed the results or drawn attention to himself. In fact, he has been virtually forgotten. Mark Spitz himself was quoted in Swimming World as saying that the Serb had won, but ultimately, it does not matter today. The results declared Phelps the winner, and thanks to this, he continues to hold the American medal record. Even without the eighth medal, it is difficult to deny, as Spitz said, that Phelps is the greatest American swimmer ever.

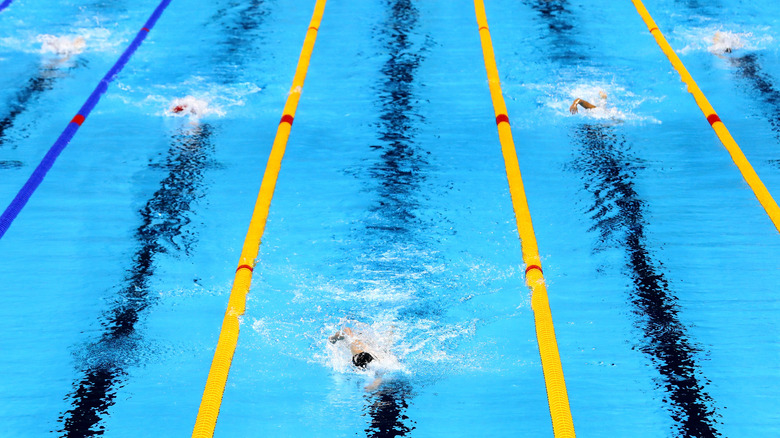

Katie Ledecky burns the pool ... twice

This "memorable moment" is composed of two different moments from two different games. Before the 2016 games, American swimmer Katie Ledecky had plenty to be proud of. At the London 2012 games, according to ESPN, she had stunned the field of more experienced athletes by winning the gold in the 800-meter freestyle at a mere 15 years old. She defeated her opponents by almost four seconds. One could be forgiven for thinking she had hit the pinnacle of her career so young, but Ledecky would outdo her already incredible achievement in Rio de Janeiro four years later.

At the 2016 games, Ledecky won medals in the 200-meter and 400-meter freestyle races. Her greatest win, though, once again, came in the 800-meter. According to The New York Times, Ledecky nearly matched the largest margin of victory — 11.7 seconds — that American athlete Debbie Meyer had set in the Mexico 1968 games. However, her time was almost 80 seconds faster than the 1968 time, leading to the conclusion that Ledecky had defeated her opponents by the same margin as Meyer while swimming faster, making her record more meaningful. At the moment she touched the pool after her last lap, the television cameras did not show any of her competitors in the frame.