How William Taft Got Tricked Into Pardoning A Dangerous Criminal

The presidential pardon has been a hot-button issue since the inception of the United States of America. According to the Brookings Institution, the executive power had its opponents among the Founding Fathers. George Mason, who we have to thank for that pretty awesome list of freedoms known as the Bill of Rights, voiced his concern that not all presidents were guaranteed to be as virtuous as George Washington. He specifically warned of the possibility of some jerk committing a bunch of crimes while president, then trying to pardon himself. "It may happen, at some future day, that he will establish a monarchy, and destroy the republic," Mason warned.

Fellow founder James Madison countered with the fact that the House of Representatives has impeachment powers, thus preventing a corrupt president from using the pardon as his own Get Out of Jail Free card. However, the country recently watched a president survive two impeachments while executing several obviously nepotistic pardons and even talking of pardoning himself, so Madison's failsafe doesn't seem to be as effective as he imagined it.

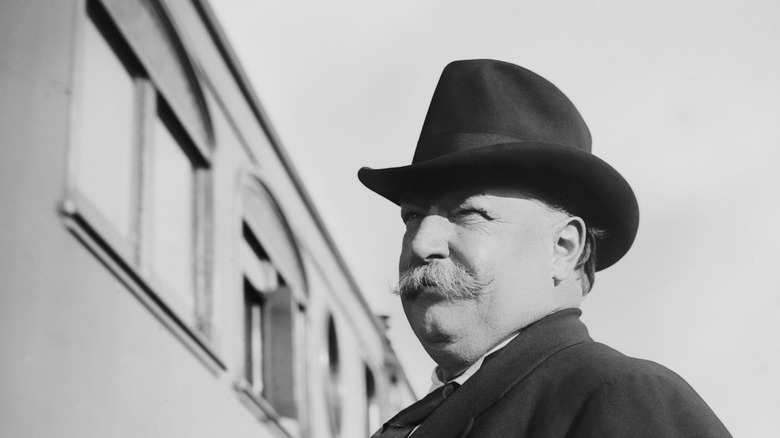

Furthermore, history has shown that presidents aren't the only ones we have to worry about being corrupt. As President William Howard Taft learned over a century ago, there are other ways for the presidential pardon to be corrupted and misused. Let's take a look at how Taft got tricked into letting a dangerous criminal go free, highlighting another way this weird executive power can be abused by the unscrupulous.

The pardon that embarrassed William Taft

On January 18, 1912, President Taft finally gave in and granted a pardon he had opposed for years. New York City banker Charles W. Morse was serving 15 years in a federal prison in Georgia for financial crimes, and he had made several appeals to Taft for a pardon, citing health issues. But Taft wasn't buying it, at first. The New York Times reported in 1911 that Taft had refused to let the guy off for a third time. The White House said in a statement that the president was "not satisfied" that Morse's health was threatened by his incarceration, despite a report saying as much from three government medical professionals.

But Morse and his team of doctors didn't back down, and Taft finally pardoned him the following year. However, as The New York Times would go on to report in 1913, Taft ended up "chagrined" after giving the supposedly sick and dying banker another go at freedom, for he somehow made a miraculous recovery right after being released. He said he had based his decision on an investigation conducted by the Army Medical Corps, but Morse's "recovery" made him think twice about believed so-called experts. "This shakes one's faith in expert examinations," he said. Whether it was a case of Morse being an excellent actor, or one of corrupt government doctors, Taft's misguided exoneration of Charles Morse reveals another problem with the presidential pardon and how its abuse can have very un-American results.