The Wild True Story Of Axe-Wielding Carrie Nation

Picture this — you're at a bar, knocking back some brews with your friends, probably watching a football or basketball game on a wide-screen TV as you talk about anything and everything under the sun. Later in the evening, you hear one of your favorite songs streaming through the bar's speakers, and you can't help but sing along, off-key as you may sound. (Who cares when you're having such a great time, right?) Life is good and so are the vibes on this random night. There doesn't seem to be anything that can ruin it for you and your buddies ... until a tall woman barges in and wrecks everything in sight with her hatchet, loudly preaching the values of sobriety and clean living as the property damage adds up. You may even hear a few Bible verses screamed out while she's at it.

That's pretty much a modern-day approximation of the havoc Carrie (later spelled Carry) Nation wreaked during her heyday as one of the leading figures of the temperance movement. Unlike others who favored more peaceful forms of protest against the perceived evils of alcohol, Nation literally took matters into her own hands, smashing up bars and saloons while spreading her message. But what led her to favor such violent methods, and what exactly went down more than a hundred years ago while she was building up notoriety as an anti-alcohol reformer? Here's a closer look at Carrie Nation and her oftentimes wild, chaotic life story.

Carrie Nation's first husband died of alcoholism

Carrie Nation was born Carrie Amelia Moore in Garrard County, Kentucky, on November 25, 1846. According to Historic Missourians, young Carrie and her family moved from state to state multiple times during her childhood, but that wasn't the only challenge she faced while growing up. Carrie grew up in poverty and was frequently ill, and this was compounded by the fact her mother, Mary Moore, dealt with mental health issues, per History.

In the 1860s, the Moore family was based in Missouri, and this was where Carrie met her first husband, a physician and former Union soldier named Charles Gloyd. They married on November 21, 1867, and had a daughter named Charlien, who was born on September 27, 1868. While pregnant with Charlien, Carrie realized that her new husband had a serious drinking problem and probably would have a hard time supporting his young family; she left Gloyd and promptly went back to her family home. Carrie's fears were further realized six months after her daughter's birth when Gloyd died as a result of "delirium tremens or from pneumonia compounded by excessive drinking," per official records.

After selling some property and her first husband's personal items, Carrie settled down on her own in Holden, Missouri. She earned a teaching certificate from the Normal Institute in nearby Warrensburg and was working as a schoolteacher when she met her second husband, David Nation.

The temperance crusade begins

As explained by Historic Missourians, Carrie Nation officially became known as such in 1874 when she married David Nation, a widower who was almost two decades her senior. David worked as a journalist and lawyer, and he and Carrie spent a few years in Warrensburg before their now-blended family moved to Texas in 1877. This is where we should remind you about one of Carrie Nation's most notable traits — she was very, very religious, and soon after arriving in Texas, she started experiencing unusual dreams and visions.

More than a decade later, in 1889, Carrie and David Nation headed to Kansas, a move that was necessitated by David's latest career change — a religious man himself, he had been asked to preach at a Christian church in the small town of Medicine Lodge. This was where Carrie first became involved in the temperance movement, which advocated for "moderation in all things healthful; total abstinence from all things harmful." As the founder of Medicine Lodge's Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) chapter, she and other women started out with peaceful protests, standing outside bars while singing religious hymns and reciting prayers.

No, this was not yet the Carrie Nation that history largely remembers; her disdain for bars and alcohol was obvious, but the axe-swinging was to come later. In the meantime, though, all the bars in Medicine Lodge that remained illegally open amid Kansas' liquor ban at the time were shut down thanks to the WCTU's protests.

A call from God to smash things up

At the turn of the 20th century, Carrie Nation heeded what she claimed was a call from God to travel to Kiowa, Kansas, to do what she did in Medicine Lodge and shut down the bars and saloons (via Historic Missourians). But instead of merely singing and praying, Nation took things to the next level by hurling bricks; she would do the same in Wichita after her work in Kiowa was done. When she went to Topeka in 1901 to close the city's alcohol-serving establishments, someone gave her a hatchet, and she was off to the races.

This was Carrie Nation as we know her today — a six-foot-tall, heavyset woman breaking liquor bottles and destroying entire bars with her axe, all in an effort to save local boozehounds from eternal damnation. The cops weren't doing much to enforce Kansas' ban on alcohol, and neither were most politicians. So what better way to get her message across than a little destruction of private property? She was, after all, a self-described "bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what he doesn't like," as quoted by PBS.

By choosing an extreme way of pushing for anti-booze reforms, Nation became quite the celebrity. She received a gold medallion from the Kansas WCTU that had the inscription "To the Bravest Woman in Kansas," and she published a few newsletters, including the aptly titled "The Smasher's Mail." Unfortunately, her fame (and infamy) came at a price. Apart from getting jailed and beaten multiple times, her husband, David Nation, filed for divorce in 1901 on the grounds of desertion, per Britannica.

The post-hatchet years: Advocacy for suffrage and other causes

Although Carrie Nation's time as a hatchet-swinging advocate against liquor was brief, she was a very influential figure well before Prohibition became a nationwide — no pun intended — thing in the U.S. But after her divorce from David Nation, she was forced to make ends meet by selling hatchet-shaped pewter trinkets and accepting public speaking engagements.

During those appearances (via Britannica), Nation didn't just condemn alcohol; she also spoke out against tobacco, pornography, foreign foods, fraternal orders like the Freemasons, and what was considered scandalous attire for women in those days, such as short skirts and corsets. She also published her autobiography, "The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation," in 1904, and starred in vaudeville shows. (Interestingly, in 1903, she legally changed the spelling of her first name to "Carry," because she saw it as more meaningful in her quest to "Carry a Nation for Prohibition," as noted by Historic Missourians.)

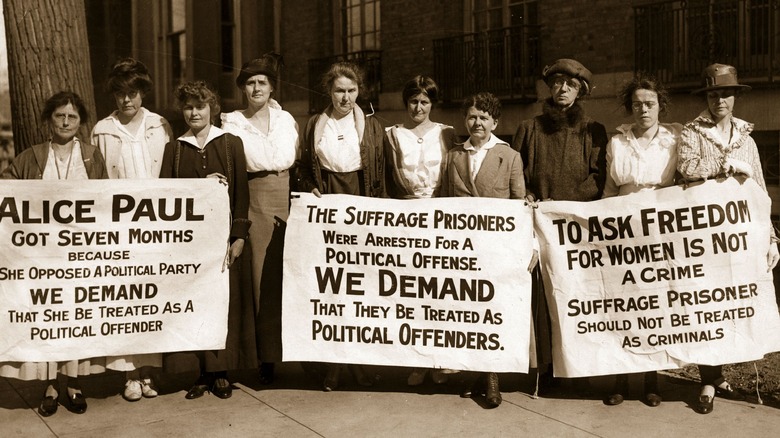

Nowadays, it's easy to see Nation as the quintessential killjoy, and during her heyday, it wasn't uncommon for her to be ridiculed, especially by bar owners who put up signs reading "All Nations Welcome But Carrie" (via Kansas Historical Society) and college students. However, she also lobbied for women's rights as a suffragist, stressing that she wouldn't have needed to resort to violence if she and other women were allowed to vote.

'I have done what I could': Nation dies months after collapsing onstage

In the latter years of her life, Carrie/Carry Nation's health began to suffer, and she moved to Eureka Springs, Arkansas, after spending a few years in Oklahoma, according to Encyclopedia of Arkansas. There, she purchased a home that later became a museum called Hatchet Hall, but initially also served as a boarding house and a school. The school was known as "National College," though it didn't offer any real college-level classes and was intended as another way for Nation to spread her pro-Prohibition message (via Kansas Historical Society).

On January 13, 1911, Nation was giving a speech in Eureka Springs, and everything appeared to be going well at first, despite the reformer's generally failing health. In the middle of the lecture, she suddenly paused, uttering "I have done what I could" before collapsing onstage. She was confined at Evergreen Place Hospital in Leavenworth, Kansas, until her death on June 9, 1911, at the age of 64. Her official cause of death was said to be paresis — a condition characterized by the weakening of one's muscles due to nerve damage, as explained by Healthline.

Nation was buried in Belton, Missouri, where her grave remained unmarked for 13 years. In 1924, the city's residents raised enough funds for a proper marker to be placed; paraphrasing her famous last words, her epitaph reads "She Hath Done What She Could."