The Tragic Story Of The Inca Civil War

The Inca state, known to the Quechua people as Tawantinsuyu (the four corners), was a massive empire of nearly 16 million people stretching from modern Ecuador to Chile. Under the leadership of Sapa Incas — emperors of the Inca Empire – the state engineered great cities in the inhospitable Andes and accumulated wealth that would later inspire the European legend of El Dorado. And yet, just like the Aztec Empire of Mexico, the Mesoamerican state fell to a tiny band of Spanish conquerors from across the Atlantic. How could such a large state be taken down by 168 people?

The Spanish were better armed than the indigenous people, and they also had disease on their side. But in the case of the Inca, the state fell from within. The fall of the Inca Empire occurred just as the new Sapa Inca, Atahualpa, had secured a glorious victory in a succession war against his brother, Huascar. Yet it was precisely this fighting within that left the Inca state vulnerable. The collapse of Tawantinsuyu lies in a civil war, which pitted brother against brother, and devastated the land, divided the nobility, and left an opening for a foreign power to decide the outcome of the war and seize Tawantinsuyu for itself. This is the tragic story of the Inca Civil War.

The Spanish wildcard

With the Inca Empire at its height, the octogenarian Sapa Inca Huayna Capac heard rumors of white-skinned, bearded men who rode strange beasts and wielded steel and gunpowder weapons. These mysterious newcomers had appeared on the coasts as early as 1515, and then appeared in the far north of the Inca lands, in what is now modern Ecuador. The new arrivals were Spanish conquistadors, lured by promises of cities made out of gold and more riches than they could ever imagine in their wildest dreams.

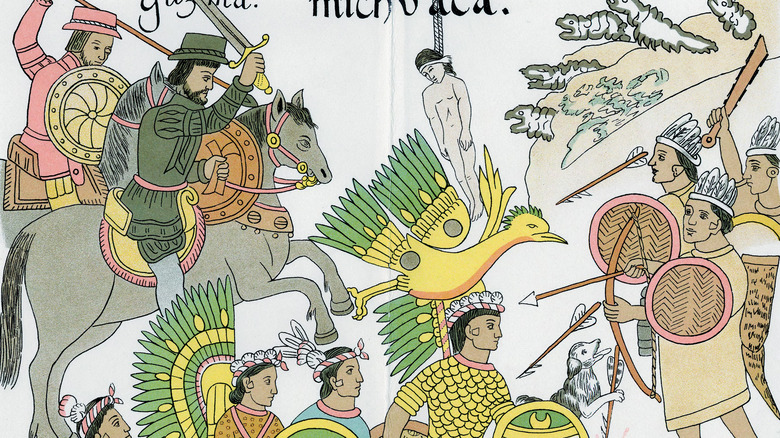

The Spanish conquest of Mexico's Aztec Empire in 1521 had set Europe alight with tales of riches, leading many more Spanish adventurers to abandon their lives and seek out their fortunes in the New World. Although they were few in number, these Spanish forces and their native allies would determine the course of the Inca Civil War — after the fighting was over and one side had triumphed.

Huayna Capac heads north, and dies

According to an account written by Spaniard Pedro de Gamboa, who accompanied conquistador Francisco Pizarro to South America, Huayna Capac received news that a tribe of cannibals called the Chirihuanas had risen up and attacked Inca territory. Huayna Capac decided not to deal with the problem personally and left the war against the Chirihuanas to his subordinates. The Sapa Inca remained in place to finish pacifying and consolidating his northern conquests and conquests.

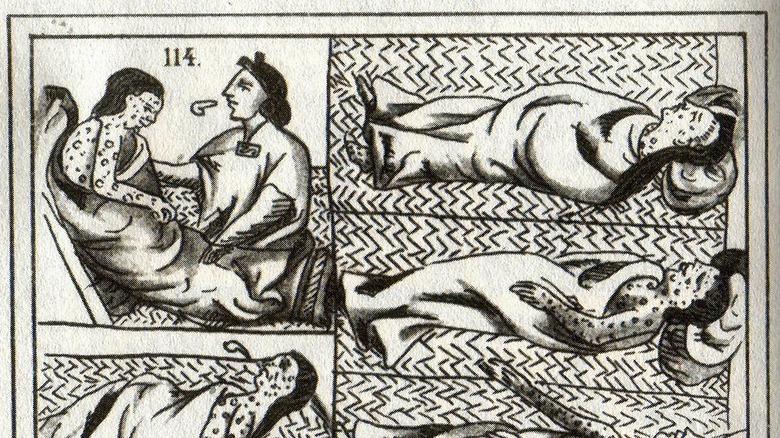

De Gamboa records that around this time, Huayna Capac received news of a devastating plague in the Inca capital of Cuzco, which had taken the lives of several family members and dignitaries. The Sapa Inca set out for home, but was taken ill with a fever in Quito. According to de Gamboa, there is little certainty about his cause of death. De Gamboa reported hearsay that the leader had contracted measles or smallpox, two Old World diseases that the Amerindian natives had no immunity against.

Seeing that his hour approached, the Sapa Inca and the nobility convened to settle the always-difficult issue of succession. Inca rulers were polygamous, so there were many sons to choose from, presenting the possibility of internecine feuds. For Huayna Capac, however, the choice was simple. His eldest son Ninan Kuyuchi would inherit, while another son Huascar moved to second in line. However, according to de Gamboa, the omens boded ill for both princes, so the Sapa Inca's steward requested he name someone else. But by then, Huayna Capac was dead. The succession had not been fully settled, leaving the nobility as the kingmakers.

Was it really smallpox?

It is worth inserting a brief excursus on the Sapa Inca's death. An Old World disease such as measles or smallpox was assumed because these maladies had devastated Mexico's Amerindian population and helped bring the mighty Aztec Empire to its knees, leaving a weakened enemy for the Spanish conquistadors and their native allies to conquer. Since the Spanish had already appeared in South America a decade before Capac's death, it seemed reasonable that such lethal diseases could spread. Coupled with de Gamboa's description, historians have generally accepted this narrative.

Robert McCaa et al. of the University of Minnesota, however, have argued that the Sapa Inca's death was most likely not smallpox. The paper's authors noted that the first smallpox epidemic recorded with certainty dates to 1558, nearly three decades after the fall of the Inca state. Even de Gamboa was cautious, noting that the death by smallpox was hearsay.

The authors note further that there were Spaniards that had seen Huayna Capac's mummy carried through the streets of Cuzco, along with those of his grandfather Pachacuti and father Tupac Yupanqui. Garcilaso de la Vega, one of these men, looked upon Huayna Capac's face but did not record any pock marks. Had the leader died of smallpox, some marks should have been prominently visible. Regardless of what caused the Sapa Inca's death, his untimely demise would have grave consequences for his empire, as his succession plans were quickly derailed and a crisis brewed.

Succession crisis

When Capac died, only Kuyuchi's succession was certain. Unfortunately, Ninan Kuyuchi did not long outlive his father, fulfilling the bad omens that the nobles had augured for him. It is thought that he died in 1525 (some sources say 1527), and it is unclear how long he reigned, if at all. The throne now fell to Capac's other son, Huascar. The problem? Huayna Capac had over 50 sons with claims to the throne. Since no heir had been definitively named, strife was inevitable. The man who challenged Huascar was Capac's most capable surviving child.

If there was anyone who believed in his right to rule, it was Atahualpa. At only 22, the young prince enjoyed immense popularity with both the army and nobility, and, according to "Conflict in the Early Americas," is thought to have been his father's favorite son. However, his lineage held him back in the line of succession in favor of his brothers. The Inca royalty practiced sibling marriages, presumably to keep the bloodline "pure." Huascar was the son of Capac's wife and sister, Coya Cusi Rimay, who was also Ninan Kuyuchi's mother. According to historian Maria Rostorowski, Atahualpa's maternal parentage is unclear. He was either the son of a northern noblewoman or of one of Capac's cousins. Regardless, he was of lesser stature than his brother. This minor inconvenience did not deter the young prince.

Split succession

To avoid conflict, Inca succession required that most of the deceased ruler's lands be apportioned to his junior sons, while the senior assumed the title of Sapa Inca. According to the University of Minnesota, this split succession resulted in a weaker center, but did not leave landless princes. Under this arrangement, Huascar and Atahualpa became the two most powerful men in the empire. Huascar ruled Cuzco, while Atahualpa received lands in the north. Despite rapidly deteriorating relations, the two brothers respected the terms for nearly five years.

Despite the peace, both brothers prepared for the inevitable succession war. According to historian John Hemming, Huascar opted to encircle his brother by allying with Atahualpa's enemies inside his own lands. He courted the fierce and independent Cañari tribe, which had repulsed multiple Inca invasions and had been conquered only with great difficulty. They hated their Inca overlords, especially Atahualpa, who had a reputation for cruelty towards his enemies. Huascar's alliance with the tribe and Atahualpa's subsequent massacres against them would have dire consequences for the Inca Empire that neither ruler foresaw until it was too late.

First blood

The Spanish chroniclers Pedro Pizarro and Pedro de Gamboa agree that at a certain point, Atahualpa refused to recognize his brother as Sapa Inca, nor pay him homage. Here, the narratives diverge. Pizarro records that Atahualpa declared himself Sapa Inca and raised an army to oppose his brother in the Cañari lands around Tumebamba. Huascar, however, was ready. Atahualpa's forces were defeated and Atahualpa was captured.

Allegedly, according to Pizarro, due to the Inca custom of not posting guards after midnight, Atahualpa escaped back to Quito. Another Spanish chronicler, Miguel de Balboa, disputed Pizarro's version of events. Balboa argued that this capture likely never happened, simply because Huascar would have executed Atahualpa immediately if he had captured him. Regardless, war was now inevitable. Atahualpa raised his armies in the north and marched against his brother in a bid to seize Cuzco in 1531.

The initial battles went in Huascar's favor. His general Atoc defeated Atahualpa's armies while the prince was fighting the Cañari, who had successfully diverted his attention from his brother's army. Despite some initial defeats, Atahualpa's men checked Atoc's advance at Mullihambato. The initiative now lay with the pretender, who took the war to his enemy's lands.

Battle of Chimborazo: Quality over quantity

Atahualpa had successfully broken the encirclement that his brother had attempted. After defeating the Cañari, Atahualpa massacred them, depriving Huascar of this strategically crucial ally. Although Huascar's armies still outnumbered Atahualpa's, the pretender had one major advantage. Three of Huayna Capac's senior generals had joined the rebels. Pedro de Gamboa noted that Atahualpa's captains were superior to those Huascar could muster. With such men at his side, Atahualpa's men advanced south.

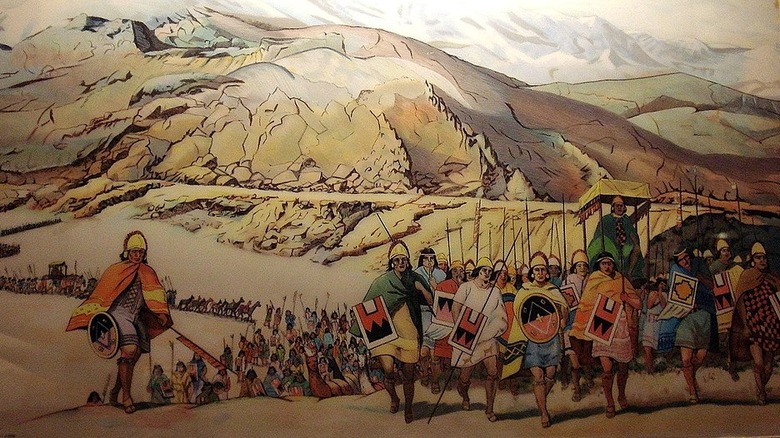

Atoc prepared to defend the road to Cuzco, and deployed his men near Mount Chimborazo to stop the rebels. Atahualpa's generals decided to fight. Not much is known about the Battle of Chimborazo. According to Conflict in the Early Americas, Atahualpa's forces scored a spectacular victory against their numerically superior opponents. Atoc was captured and tortured to death. Most importantly, the road to Cuzco was now open. Atahualpa's armies continued south, hoping to capture the capital and end the civil war with one decisive final battle. Thus, peace would be restored to the empire under a single Sapa Inca.

Victory at Quipiapan?

In 1532, Huascar marched out personally to face his brother in the field outside Cuzco. At Quipaipan, Huascar had the better of the initial fighting, forcing Atahualpa's generals into a ravine where he intended to destroy them once and for all. Pedro de Gamboa records that Atahualpa's generals spectacularly turned the tide of battle using Huascar's overconfidence against him. As Huascar believed to have his enemies cornered, he sent a force to engage them until he could arrive to finish them off. Atahualpa's generals ambushed this first force and then captured Huascar as he and his reinforcements entered the ravine. After leaving Huascar under guard, Atahualpa's men attacked and routed the demoralized main army.

De Gamboa records that the imperial army fled. Atahualpa's men pursued and cruelly slaughtered them all. The rebels occupied Cuzco and captured Huascar's family. His female relatives in particular were singled out for humiliation. The civil war was over. Atahualpa had won. All he had to do was march to Cuzco to claim his throne and he would be the Sapa Inca, the most powerful man in South America. Unfortunately for Atahualpa, the battle did not herald the end of the war. Before the Battle of Quipaipan, Atahualpa is said to have visited an oracle in Huamachuco. The seer declared that Atahualpa would meet a bloody end for his cruelty. Atahualpa had the oracle tortured and killed. Soon after, he heard sobering news. Spanish forces under Francisco Pizarro together with Cañari allies, had appeared in the north near the town of Cajamarca.

From civil war to survival war

Although Atahualpa had won the civil war, the fighting had torn the Inca Empire apart. Now, Atahualpa faced a far more difficult enemy: Francisco Pizarro's Spanish forces. Despite only having 168 men, Pizarro was hungry for gold and adventure, and headed toward Cajamarca in the northern Inca lands, where Atahualpa stayed during the civil war.

When Pizarro and Atahualpa met — through an interpreter — Atahualpa received them warmly. However, a monk in Pizarro's retinue requested to speak to the Sapa Inca. According to English scholar George Towle, Fr. Vicente demanded that Atahualpa convert to Catholicism and acknowledge Holy Roman Emperor and Spanish King Charles V as his overlord. Atahualpa, as expected, having no idea whom or what he was up against, refused to convert and offered Charles his friendship, but refused to submit. Now the conquistadors might have accepted this refusal peacefully, until Atahualpa made the mistake that would cost him his throne and his life.

During the exchange, Fr. Vicente offered Atahualpa a religious book, perhaps a breviary or a Bible. When he did not hear it literally speak to him, the Sapa Inca threw it to the ground, an act of sacrilege for the Spaniards present before him. At this point, Pizarro ordered his men to attack the Incas. Despite being outnumbered almost 600:1, the Spaniards had surprise, novelty, and fear on their side. The Inca scattered and Atahualpa was captured.

The ransom room

After his capture, Atahualpa was treated well. According to Towle, he was allowed to receive dignitaries as if he were the Sapa Inca in his own right, and Pizarro allowed the prisoner's many wives and concubines to visit. He even learned how to speak and write Spanish. However, he was still a prisoner, and the civil war had not been completely won. Huascar was still alive, albeit imprisoned in the Andes. Atahualpa offered Pizarro a ransom room filled to the brim with gold and silver in return for his freedom. The Spaniard accepted.

Husacar, meanwhile, is said to have attempted to contact Pizarro, offering him a large amount of gold and silver if he would free him. Atahualpa somehow discovered the plot. According to de Gamboa, Pizarro had entertained the possibility of deciding the final outcome of the Inca Civil War himself. Atahualpa had ordered Huascar to be turned over to the Spaniards, but the Sapa Inca, who had not realized that the Spaniards were in Peru to stay, feared that Pizarro would hand his brother the throne. He secretly ordered loyal nobles to kill Huascar, who was thrown into a river and drowned.

Pizarro was furious at losing his bargaining chip, and some of his commanders talked openly about killing the Sapa Inca. Pizarro resisted, but according to Towle, one of Atahualpa's enemies is said to have come to the Spanish camp and spread rumors that Atahualpa had summoned an army to rescue him. Once this rumor spread, Atahualpa became an object of hate among the conquistadors, who near-unanimously demanded his death for his dishonorable behavior.

The fall of Tawantinsuyu

Pizarro refused to execute Atahualpa without a trial. The Sapa Inca was accused of fratricide and of treasonous behavior (although he had never sworn allegiance to Spain). Despite a few voices calling for mercy, Atahualpa, as a non-Christian, was sentenced to burn at the stake, a long, painful death usually reserved for heretics.

Before his execution, Atahualpa is said to have spoken to Pizarro and demanded to know what he had done to deserve his fate. Despite opening up his court to the Spaniards and receiving them hospitably, he was now to die and see his people conquered by a far-away foreign power. Pizarro is said to have nearly shed tears, but could not overturn the sentence at this point without inciting a mutiny among his own men. Atahualpa advanced toward the stake, was tied, and prepared himself for death.

At the last minute, Atahualpa received mercy. According to the Australian National University, Fr. Vicente offered Atahualpa the possibility of a faster, less painful, and more merciful death if he accepted baptism. Atahualpa relented and was quickly baptized, incredibly taking the name Francisco in honor of the man who was about to execute him. Afterwards, he was quickly strangled.

In a matter of months, Atahualpa had gone from being the victorious Sapa Inca of Tawantinsuyu to being the last Sapa Inca, left to die a humiliating death at the hands of his foreign captors. Despite his cruelty and arrogance, Atahualpa was a skilled ruler and captain. The circumstances of his death and rapid fall from grace at the pinnacle of his power, cannot be considered anything other than tragic.