What It Was Really Like The Day Marilyn Monroe Died In 1962

The death of Marilyn Monroe has become a bookmark in American history: People who were alive when it happened can pinpoint where they were when they heard the news. Six decades on, the conspiracy rumor mill has never stopped swirling, spitting out new theories every few years.

It's ironic, then, that no one knows exactly when Monroe died. One of the most beloved celebrities in Hollywood died alone, in her bed, of what was deemed a probable suicide. She was last seen alive on the night of August 4, 1962, and that's the last time she talked to anyone on the phone. She was found dead in the early hours of August 5. It took even longer for the news to spread around the country. August 5 was a Sunday, and although radio stations put out bulletins, the newspapers didn't report her death until the following Monday, August 6.

Monroe had been having a bad year in 1962, and depending on who you ask, she was either at the trough of a major slump or primed for a comeback when she died. Taking into account the reactions of her three ex-husbands, the press, and a certain pop artist, along with simultaneous major world events and, yes, conspiracy theories, this is what it was really like the day Marilyn Monroe died.

Given the nature of Monroe's death, this article discusses suicide: If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The timeline of Marilyn Monroe's death is in dispute

Exactly when Marilyn Monroe died is still unclear. Several key witnesses changed their stories over the years, most notably Monroe's housekeeper, Eunice Murray, who was the first to raise the alarm. Murray said that Monroe went to bed around 7:30pm on Saturday August 4, 1962, and that was the last time she saw her alive. Two other witnesses — actor Peter Lawford (brother-in-law to John and Robert Kennedy) and Joe DiMaggio Jr. (Monroe's former stepson) — said they spoke to her on the phone around that time, but their accounts of her mood contradict each other.

Murray continued that she knocked on Monroe's door at around midnight, and when there was no answer, she called Monroe's psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson. Greenson and Murray went outside and saw through the first-floor bedroom window that Monroe was lying motionless, face down on her bed. Murray and Greenson broke into the room through a window. Unable to rouse Monroe, Greenson called her physician, Dr. Hyman Engelberg, who arrived a little while later. The LA Times reported that at 4:20am, Engelberg called the police and reported that Monroe was dead. They got there five to 10 minutes later.

This account leaves a significant gap between Murray finding the body and the police being called. Murray later changed her story, saying that she found Monroe at around 3am, after noticing light under her bedroom door, and being unable to wake her or get into the room.

The press was caught off guard by Marilyn Monroe's death

The first time people outside Marilyn Monroe's inner circle knew about her death was early on Sunday morning: Vanity Fair has Dr. Engelberg calling the police at around 4:30am on August 5.

The two major news agencies at the time were the United Press (UP) and Associated Press (AP). Newspapers bought stories from them and duplicated stories for them, or tipped them off. Hank Rieger, who worked for the UP, told an interviewer that he found out about Monroe's death through a tipster at the LA Times. He recalled getting a phone call at home at 1am — eyebrow-raising, given the timeline. The AP had recently started closing overnight, giving the UP an opportunity to scoop its rival and break the news. Rieger confirmed the information with the police, but couldn't get any more details. He dispatched reporters to Monroe's house, and to the morgue. Reporter Joan Sweeney climbed over the fence at the latter, and got into the office where Monroe's body was being held — another UP scoop.

If you think that's distasteful, just wait.

In August 2019, Devik Wiener told a Fox News documentary series that his father, photographer Leigh Wiener — who had worked with Monroe — bribed his way into the morgue and took photos of Monroe's naked, dead body. Leigh developed the photos, his son said, but decided they were too grim for the public, and hid them in a safety deposit box. Thankfully, they've never been found.

The press honed in on Marilyn Monroe's drug use

It wasn't until Monday, August 6, that major newspapers made Marilyn Monroe's death front-page news. Bernie Taupin and Elton John's famous tribute to Monroe, "Candle in the Wind," would later claim that "All the papers had to say/Was that Marilyn was found in the nude." In fact, the newspapers were at least as interested in another salacious detail: the drugs at the scene.

The New York Times, BBC, LA Times, New York Daily Times and Variety all reported on the empty bottle of Nembutal, a sleeping medication, that was found near Monroe's body. According to the LA Times, it had been prescribed by Dr. Engelberg just a few days before her death, and had contained 40 to 50 capsules when filled. The New York Times added that the nightstand held 14 other medication bottles. PBS later reported that Monroe was known to regularly mix barbiturates, opiates, amphetamines, and alcohol.

By August 6, LA County Coroner Theodore J. Curphey had told the press that an autopsy had showed that Monroe likely died of a drug overdose, and later described her death as a "probable suicide." However, medical examiner Dr. Thomas Noguchi, who performed the autopsy, eventually admitted that samples from Monroe's intestines and stomach were lost before they could be put through toxicology tests. This has fueled conspiracy theories, but a 1982 investigation by the LA District Attorney agreed that Monroe's death was likely caused by an overdose, whether intentional or accidental.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

The speculation over Marilyn Monroe's state of mind in her final moments

No one can know exactly what was going through Marilyn Monroe's head in her final hours and moments. But that hasn't stopped plenty of people — relevant and otherwise — piling in with their opinions. One school of thought has Monroe more depressed than ever just before her death. She was divorced from her third husband, Arthur Miller, and during the marriage she had been through several miscarriages. Career-wise, her last two movies had been disappointments at the box office. On top of that, 1961's "The Misfits" had been tainted by disagreements with Miller, who had written the script, including a part Monroe felt was too close to herself. She'd also recently been fired from the movie "Something's Got to Give," co-starring Dean Martin.

In contrast, some have argued that despite her concerning drug and alcohol use, Monroe was slowly turning a corner. She'd bought her first home in March 1961, and was adding her personal touches to it, planting a herb garden and ordering furniture and tapestries from Mexico. According to the BBC, she and Joe DiMaggio were planning to remarry soon. And she was returning to work on "Something's Got to Give."

Even the people who were with Monroe or spoke to her on her final day disagreed over her mood. We'll never know what she was feeling: it may be the one secret the world's most famous woman managed to keep for herself.

There are different versions of what happened the day Marilyn Monroe died

There are many conspiracies around Marilyn Monroe's death. All are far more elaborate than the explanation that the actress — who was known to use drugs and alcohol haphazardly — accidentally or intentionally overdosed. Possibly the most famous conspiracy involves Robert F. Kennedy, then-Attorney General and brother of President John F. Kennedy. The story goes that Monroe had affairs with both Kennedy brothers, and wrote down details — and state secrets — in a diary that mysteriously went missing after her death. (The BBC reports that Monroe did keep diaries, but even those didn't stay private: extracts were published in 2010.)

According to the LA Times, Peter Lawford's ex-wife Deborah Gould and private detective Fred Otash have both claimed that Robert Kennedy was present the night Monroe died, and an argument between them pushed her to suicide. They said that Lawford — then married to the Kennedy brothers' sister Patricia — helped smuggle Robert back to Northern California to avert suspicion, and destroyed evidence. Another conspiracy has Robert — or the mob — murdering Monroe with a Nembutal suppository.

Lawford, unsurprisingly, denied these accusations. His fourth wife (later widow) confirmed that Lawford did work with Otash, and he called him the night Monroe died, but she claimed it was regarding Monroe's apparent suicide. Lawford admitted that he spoke to Monroe the night of her death, and said that he was gravely worried that she was suicidal — not that she was about to be murdered.

Marilyn Monroe's unfinished final movie was scrapped when she died

Marilyn Monroe had been poised to make a triumphant return to a movie she had previously been fired from when she died suddenly. Monroe could be magic on camera — but capturing that magic was a grueling process. She had terrible stage fright and anxiety, and struggled to remember her lines. She showed up late if she showed up at all. Her drug and alcohol addictions exacerbated the issues.

In 1962, Monroe was assigned to "Something's Got to Give," a remake of a 1940 movie, opposite Dean Martin. She frequently failed to turn up to set, the LA Times reports, usually citing illness. And she had been ill: since finishing "The Misfits" 18 months previously, Monroe had had surgeries to treat endometriosis and remove her gallbladder, and had been treated in a psychiatric clinic after divorcing Arthur Miller.

On June 1, Monroe turned 36 on set. On June 8, having missed 17 of the 30 shooting days so far, she was fired from "Something's Got to Give." Fox cited what it called "willfully disruptive" behavior. However, Monroe's co-star Martin rebelled, refusing to work with any other actress. Monroe took to the press to prove that she was not only capable of working, but a draw for fans. On August 1, she was rehired to the production. When she was found dead on August 5, the movie was canceled for good: however, some of the footage has since been released.

Joe DiMaggio was devastated by Marilyn Monroe's death

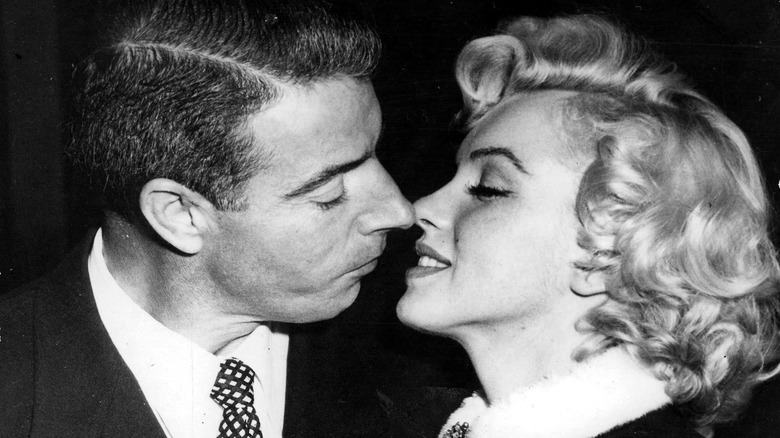

On January 14, 1954, less than two years after meeting, Marilyn Monroe and baseball star Joe DiMaggio eloped. However, arguments over her career and inability to conceive saw Monroe file for divorce in October 1954, citing mental cruelty. Despite their short and tumultuous marriage, Monroe and DiMaggio eventually became good friends. When Monroe was admitted against her will to a psychiatric hospital in 1961, she called DiMaggio for help and he got her out, the New York Times reports. There were rumors that the couple had planned to remarry before her sudden death.

According to the Washington Post, DiMaggio learned of Monroe's death from his sister, who had heard the news on the radio. He immediately flew to LA, collected her body, and took charge of funeral arrangements, with help from Monroe's business manager Inez Melson, whom DiMaggio had recommended. (Vanity Fair calls her DiMaggio's "spy.") DiMaggio spent the night of August 5 sitting with Monroe's body. He even picked out the green sheath dress Monroe was buried in.

DiMaggio refused to allow many of Monroe's Hollywood connections to attend her funeral, reportedly saying, "if it wasn't for them, she'd still be here." One of his friends later said that he blamed Monroe's death on the Kennedys. And DiMaggio used Monroe's funeral to start a sentimental tradition: he had six red roses delivered to her crypt three times a week. He only stopped in 1982 because it was drawing too much attention.

Arthur Miller had no public comment when Marilyn Monroe died — but he was privately angry

Marilyn Monroe met her third husband Arthur Miller the year before meeting her second husband Joe DiMaggio. It was on a movie set in 1951: Miller was married and Monroe was having a fling with one of his friends. Four years and one divorce — Monroe's and DiMaggio's — later, they started an affair. Miller eventually got a quickie divorce in Reno, Nevada, and on June 29, 1956, he and Monroe legally married. The couple had a Jewish ceremony two days later, which Monroe had converted for.

To make a drawn-out and painful story short, Miller and Monroe's marriage was undermined by his snobbery and her emotional issues. They split while making the movie "The Misfits" — written by Miller, starring Monroe — and announced their divorce on November 11, 1960. Miller remarried a year after the separation.

On August 6, 1962, the day after Monroe's body was found, the New York Times reported that when Miller was asked if he had a comment on her death, he was typically aloof, saying, "I don't, really." Miller was criticized for not attending Monroe's funeral on August 8. However, in an unpublished essay written that day and made public in 2018, he expressed his anger with the Hollywood elite and executives he felt had "destroyed" Monroe. In the essay, he expressed a sentiment Joe DiMaggio apparently shared, writing, "let the public mourners finish the mockery ... Most of them there destroyed her."

Marilyn Monroe's first husband was one of the first people to learn of her death

Marilyn Monroe's second and third husbands were famous in their own rights: But it was her first husband whose unstarry job meant he was one of the very first people to hear about her death. Monroe married James Dougherty on June 19, 1942, less than three weeks after her 16th birthday, when he was 21. Back then, her name was Norma Jean Baker. Without going into the whole tragic real-life story of Marilyn Monroe, suffice it to say that Monroe was raised by a series of foster families, and they hoped this marriage to a kind neighbor would give her stability.

Dougherty joined the Merchant Marines in 1944, and was soon dispatched to the South Pacific. In the meantime, Monroe started working on her modeling and acting career. She divorced Dougherty in 1946. Dougherty remarried soon after, and became a police officer in Los Angeles. He was on patrol when a colleague who had been to Monroe's house called to tell him that she was dead. According to Dougherty's LA Times obituary (he died in 2005), he avoided reporters that day by driving around in his squad car.

Dougherty later became less press-shy, giving interviews about their marriage and what Monroe was like as a young woman. In comments reflecting those of Monroe's other ex-husbands, he told CNN in 2003, "she was such a pure and innocent soul. The movie industry abused her and used her."

Nelson Mandela's arrest made history the day Marilyn Monroe died

Before the conspiracy-minded get overexcited, Nelson Mandela has no direct connection to Marilyn Monroe's death. But like Monroe, he did join the history books on August 5, 1962 — and there are conspiracies surrounding that incident too. By the summer of 1962, Mandela had become a leader in the African National Congress (ANC), a political party that had been protesting against South Africa's apartheid laws since the early 1950s. When the ruling National Party outlawed the ANC in 1960, the party switched from peaceful protests to sabotage and guerrilla warfare.

In 1961, Mandela was appointed head of a new, militant branch called Umkhonto we Sizwe ("Spear of the Nation"). He was so good at evading the government that he became known as the Black Pimpernel, the BBC reports. So it was somewhat surprising on August 5, 1962, when Mandela was pulled over at a roadblock in Durban, South Africa, and arrested. He was convicted of leaving the country illegally and of inciting strikes, and sentenced to five years in prison. This was increased to a life sentence two years later: Mandela wasn't released until 1990.

The South African secret services had help finding Mandela the night he was arrested. The CIA saw Mandela as a Communist, and worried that the U.S. might get dragged into a Cold War confrontation if there was a South African civil war. So operatives tipped off the South African police as to Mandela's whereabouts that night.

Celebrities were just as shocked by Marilyn Monroe's death

Although many people who knew Marilyn Monroe weren't surprised that her issues with drugs and alcohol ultimately caused her death, they were still shocked and upset. On August 6, the New York Times reported that actress Sophia Loren cried when she heard the news. The newspaper also wrote that Kay Gable — whose late husband, Clark Gable, had worked with Monroe on what proved to be their shared final finished film, 1961's "The Misfits" — went straight to Mass to pray for the dead woman.

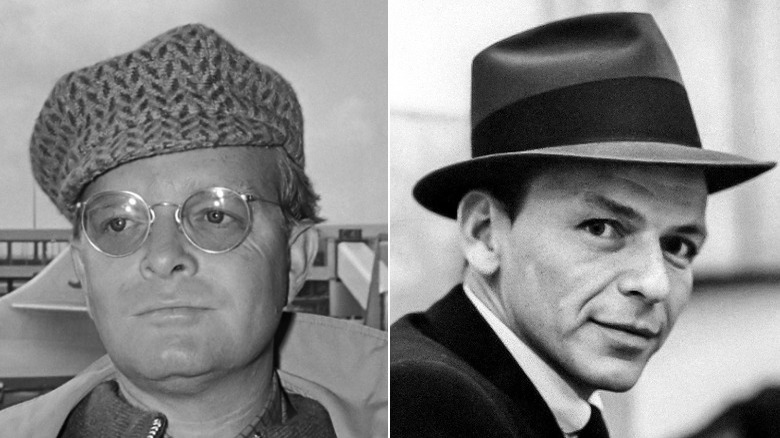

According to Vanity Fair, author Truman Capote put aside his trademark acerbic wit, writing that he couldn't believe Monroe was dead: "She was such a good-hearted girl, so pure really, so much on the side of the angels." Meanwhile, Monroe's close friend Frank Sinatra heard rumors from the lawyer they both used, Milton "Mickey" Rudin, who was one of the first to arrive at Monroe's house, that she had been murdered by the mob or the Kennedys, according to a book written by his road manager.

One person whose response many people were interested in was the wife of the man Monroe had supposedly had an affair with. That would be First Lady Jackie Kennedy. Jackie remained characteristically demure on the subject, at least in public. But after the assassination of her husband on November 22, 1963, she expressed empathy with Monroe's probable suicide, telling a priest, "I was glad that Marilyn Monroe got out of her misery."

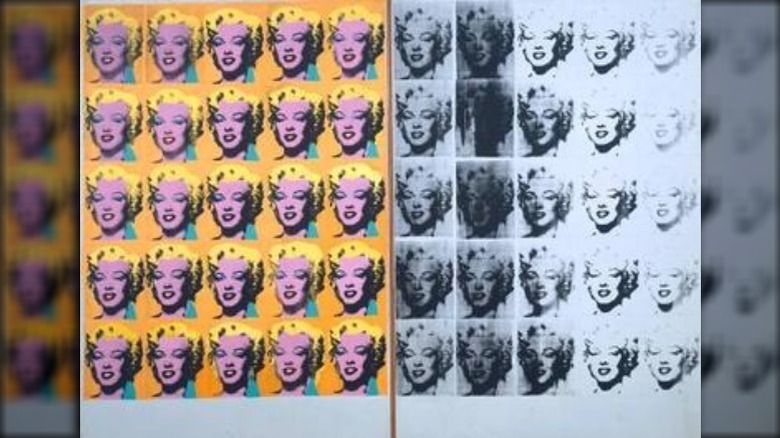

Marilyn Monroe's death immediately inspired one of the world's most recognizable works of art

The day Marilyn Monroe's death made headlines — August 6, 1962 — coincided with the 34th birthday of a commercial artist who had long been fascinated by her. Andy Warhol immediately started working on a piece that has endured in parallel to Monroe's own fame. Dubbed "Marilyn Diptych," it would be the first of several artworks Warhol made featuring Monroe's image.

Back then, Warhol's day job was drawing pictures for ads. In his spare time, he poured his expertise in branding into creating Pop Art. As the Tate Modern writes, he'd recently started making photo-silkscreen pictures, including the series "Campbell Soup Cans." To Warhol, Monroe was the perfect example of intoxicating Hollywood celebrity, which saw stars repurposed as brands. He was also intrigued by death: he followed "Marilyn Diptych" with what grew into the "Death and Disaster" series, featuring screen prints of car accidents and other tragic scenes.

Using a publicity still from Monroe's 1953 movie "Niagara," Warhol printed her face 50 times in a grid. The faces on the left were colored in garish orange and turquoise paint, and the right side remained silver, black, and white, fading at the edges. The work showed the contrast between Marilyn the movie star, painted to attract attention, and Marilyn the person, always just out of view from her adoring public. Marilyn Monroe was dead: but her famous face would always be frozen in time, never evolving and never forgotten.