The Untold Truth Of The Merry Pranksters

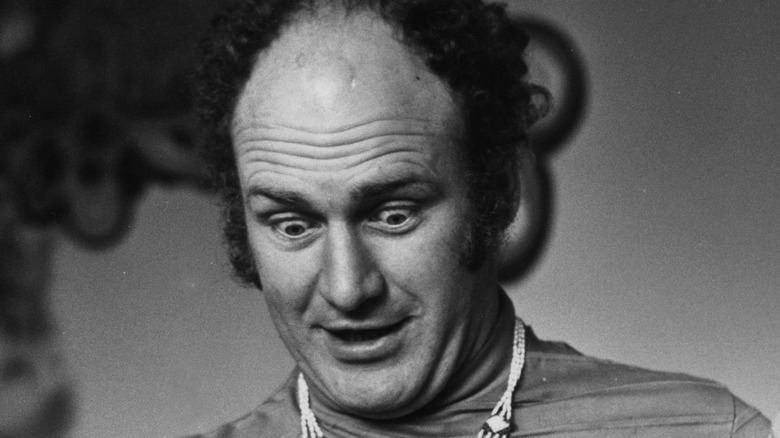

If America is an open road, then the American counterculture of the 1960s is best described as a bus, hand-painted and packed with people, roaring toward the horizon. Immortalized in Tom Wolfe's cult classic "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test" and imitated by generations of young movements looking to go against the grain of society, the road trip made by novelist Ken Kesey (above) and a dozen friends in the summer of 1964 has become an iconic symbol of a certain formulation of freedom in America.

Ostensibly, the journey was undertaken to visit the highly-anticipated 1964 World's Fair, which was taking place in New York City, but there were other motivations at work. As the common myth would have it, the journey was also about spreading the gospel of a new mode of perception that Kesey had anticipated might take root with the use of psychoactive drugs. As Wolfe puts it: "The trip had a dual purpose ... one was to turn America on to this particular form of enlightenment, the other was to publicize [Kesey's] new book 'Sometimes A Great Notion'" (per The Guardian).

The origins of the Merry Pranksters

Kesey had become a major literary celebrity by 1964, thanks to the instant success of his 1962 debut novel, "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," the plot and characters of which were heavily indebted to his prior work as an attendant in the mental facility of Menlo Park Veteran's Hospital, near Palo Alto, California (per Biography). But the writer had also had his own experiences of altered perception, thanks his participation in clinical trials conducted by the U.S. Army and the CIA in 1959 that were intended to study the effects of LSD, which authorities had hoped could be used as a tool to aid interrogations, according to The New York Times. Kesey had already taken LSD at the time he was writing his immense bestseller, but it was in the years following this — and the completion of his second novel, "Sometimes A Great Notion" — that he began to see psychedelic drugs as an important tool in promoting his ideas of non-conformity and societal freedom, ideas he shared with a close circle of like-minded friends.

"We weren't old enough to be beatniks, and we were a little too old to be hippies," said Kesey (per MPR News). "Everybody I knew had read [Jack Kerouac's novel] 'On the Road.' It stirred us up, so we decided to travel across the country. Because there were so many of us, we decided to buy a bus."

Catching the bus to 'Further'

"You're either on the bus or off the bus," Kesey often said, according to Mark Christensen's biography of Kesey, "Acid Christ," which paints the Merry Pranksters as a "Beta house fraternity on wheels." The Pranksters named the bus "Further," as an indication that they were pushing towards a new frontier.

As explained in Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood's 2011 documentary "Magic Trip," which recounts the Merry Pranksters' journey to the 1964 World Fair in New York City using original footage filmed by the Pranksters themselves, Kesey saw the journey as a means to "open things up" in American society. In this case, the word "trip" certainly serves a double meaning: Kesey supplied his cohort with copious amounts of LSD, mixed into jars of orange juice (according to The Guardian), which the Pranksters would imbibe regularly on their travels, ever widening their sense of the possibilities of a different America as they did so.

The Pranksters were also habitual cannabis smokers, while several of them took amphetamines, including the group's legendary driver, Neal Cassady, the Beat Generation icon who was the inspiration for Dean Moriarty in Jack Kerouac's "On The Road." Cassady would take speed to keep him awake during marathon driving sessions, sometimes staying at the wheel for days on end, babbling incessantly to anyone who would come to sit in the passenger seat.

How the Merry Pranksters got away with it

When Kesey first purchased "Further" (sometimes "Furthur"), it looked just like a regular 1939 yellow school bus. However, by the time it hit the road, it was already a technicolor marvel, the colors of which would lay the blueprint for psychedelic artwork throughout the 1960s. "Magic Trip" (posted on YouTube) reveals that Further was painted and repainted some 5-10 times in the early days, and the bus attracted plenty of attention — as was Kesey's intention — though much of this was from the police. So how did a bunch of drugged-up proto-hippies get away with it?

As well as LSD, a dozen Merry Pranksters, and a range of musical instruments — which the Pranksters could play with varying degrees of ability — Further was carrying a load of film gear: cameras and sound equipment with which Ken Kesey hoped to document the Pranksters' journey.

"We had this movie that we were going to make called 'Intrepid Travelers,' and this merry band of pranksters look for a cool place — the cool place that exists in you in your mind and your body," said Kesey's school friend and fellow Merry Prankster, Ken Babbs (per KQED). So whenever the Pranksters found themselves encountering the police, they got their equipment out, and told the officers that they were filming a movie. The hippie movement was yet to begin, and the police were unaware of psychedelics, though hippies would become demonized for their use of LSD later in the decade.

Downers among the highs

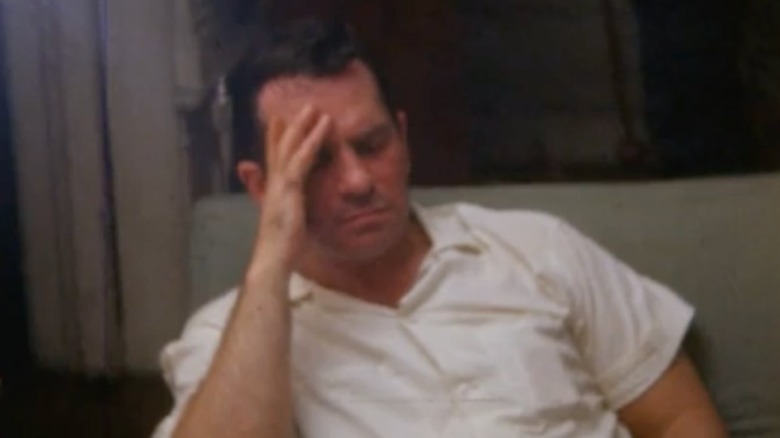

The Merry Pranksters' debut journey in the summer of 1964 was characterized by numerous disappointments and incidents that undermined the group's utopian ideals. The first was the World's Fair itself, which the Pranksters explored upon their arrival in New York but which ultimately didn't provide the inspiration for further psychic inspiration that Kesey and his band had been anticipating (per "Magic Trip," posted on YouTube). The second was a party in New York, where the Pranksters had the honor of meeting Beat heroes Jack Kerouac (pictured above, at the party) and Allen Ginsberg. But the meeting didn't go as planned; Kerouac's youthful vivacity that made him a countercultural hero had long since vanished, and the elder writer was irritated by the Pranksters and found no connection to Kesey. He reportedly left after an hour.

The Pranksters were similarly let down when they took a detour on their return trip to visit the home of Timothy Leary, a fellow LSD proponent who, on the surface, shared many interests with Kesey and his group. However, as The Guardian notes, the two differed wildly in how they imagined the drug might be integrated into society, and Leary failed to properly welcome to the Pranksters.

Also on the return journey, Cathy Casamo — an actress who had joined the Pranksters shortly before their trip — suffered a psychotic episode as a result of her LSD use. The Pranksters left her in Texas, and set off on the road without her, according to the account on her website.

The end of the dream

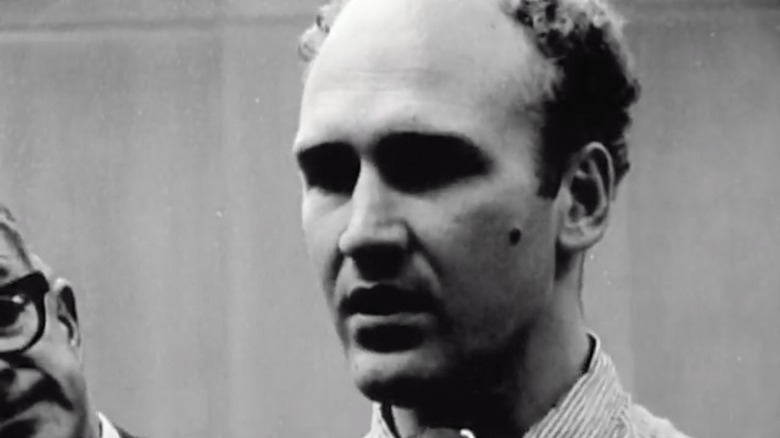

After their return to California, the Merry Pranksters began introducing American youth to LSD by staging a series of "Acid Tests," events that quickly became famous, but it was not to last. In April 1965, Kesey (pictured) and 13 of his Pranksters were arrested in a police drug bust at his home, with the writer receiving a five-month prison sentence (per The San Francisco Chronicle), after which Kesey began to distance himself from both LSD and the Pranksters.

Neal Cassady suffered a terminally tumultuous few years following the first Pranksters trip, though he was a regular feature at the Acid Tests. "Once he didn't have the bus to drive or a function, he was really like a liability," said Merry Prankster Jane Burton (per "Magic Trip"). In February 1968, Cassady was found collapsed alongside a railroad track in Guanajuato, Mexico. His cause of death is still debated, though he was known to have taken barbiturates (per The Guardian). He was 42.

Now known as catalysts for the hippie movement, the Pranksters attended Woodstock in 1969, but Kesey wasn't among them. He would later claim that he thought drugs had become a fashion statement, and often sought to disassociate himself with the hippie movement. Kesey remained active as a writer and speaker throughout his life. He died from complications of liver cancer on November 10, 2001. He was 66.