Past Predictions About The Future That Were Way, Way Off

The future is always in front of us, brimming with of possibilities: rocket pants, chorus lines of robo-legs kicking high to songs about android dreams, and, of course, those ubiquitous flying cars. Who doesn't want one of those? Since well before the days of Nostradamus, seemingly prescient women and men sought to predict the ways of our successors. Sometimes, their concepts proved to be startlingly accurate, but most often, their visions were off by several light years.

Fred Freedman's fantastic future

The 1960s were rife with amateur and professional soothsayers dreaming humankind up a Jetsons-like reality. One of these predictive persons was noted "futurist" Fred Freeman. His party-free vision of the far-off world of 1999 turned our distant selves into quite the spectacle. He pictured us rocking rocket belts as we zipped around our sweet domed cities. If we needed to get from point A to point B, no problem: just hop in a hover-car and fuhgeddaboudit.

Admittedly, Freeman's intriguing concepts fell rather flat on their futuristic faces (how do you accessorize a rocket belt, anyway?). These days, hover cars are still less-probable than cars that drive themselves. If there was anything the great visionary did get right, it was moving sidewalks. Of course, we only get to enjoy this form of mass transit when we're biding our time between planes at the airport. Nevertheless, there's something magical about cruising along at speeds just barely above the foot traffic next to you.

Edison bets on steel

Without a doubt, Thomas Edison was one of the most brilliant inventors of the early 20th century. Known for the long-lasting lightbulb, the phonograph, and the peep show viewer (Kinetoscope), among many others innovations, his insight made possible many of the marvels we enjoy today, lighting the way for the high-tech contemporary culture we treasure. Of course, ol' Tom wasn't one-hundred percent on the ball at all times.

Edison's unique vision for tomorrow inspired many incredible advances, but his prediction regarding the future of construction material rang a bit hollow. See, Edison either thought a great deal about the new steel alloys or was heavily invested in Pittsburgh's chief industry at the time. As a result, he claimed the future belonged to steel. Every aspect of our homes, from baby cradles to rocking chairs to boudoirs, would be "sumptuously equipped with" the dense, metallic alloy. There's no doubt that steel still plays a major role in building construction and cookware, but heft and relative durability issues gave other composites like aluminum, fiberglass, and plastic the advantage in contemporary construction over old Andrew Carnegie's main squeeze. If Edison had only foisted the mantle of the future onto petroleum byproducts, he'd have chalked another notch on his prophetic belt.

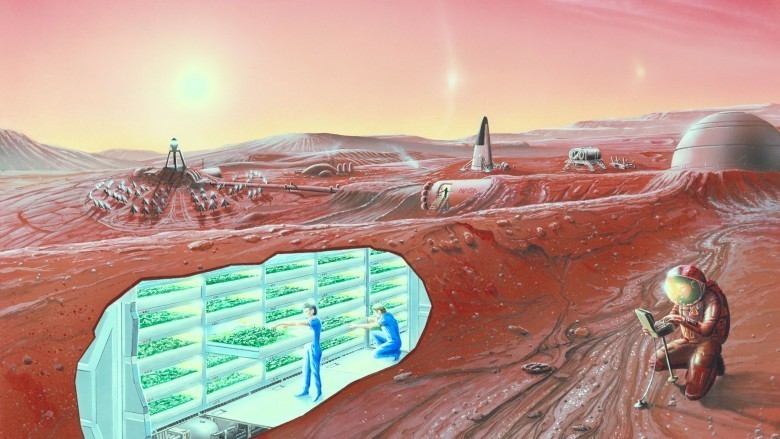

The Martian Chronicler falls short

Responsible for dozens upon dozens of short stories, as well as classic novels like Fahrenheit 451 and several film adaptations and inspirations, Ray Bradbury made science fiction cool, or at least mainstream. The average reader may not be familiar with his classic dystopian stories such as "There Will Come Soft Rains" or "The Veldt," but have probably heard of The Butterfly Effect (loosely inspired by his story "A Sound of Thunder") as well as his disquieting Disney adaptation Something Wicked This Way Comes. Then there's his highly influential sci-fi saga The Martian Chronicles, which document colonial life on the planet Mars (not on Bruno or Veronica, just to clarify).

Speaking of which, Bradbury's often terrifying and prescient conceptualization of the future sometimes got a little bit ahead of itself. Back in 1950, the prolific author predicted that nuclear war would force us onto Mars by the 2000s. Fortunately, we were too busy "drinking beer and watching soap operas," to quote Mr. Bradbury, to make the colonization of Mars happen. Hey, at least we launched that rover thingy, right?

Colonization technology may be in its infancy, but NASA and other high-tech companies are working on landing humans on the red planet. Bradbury's futurism, if a tad optimistic, continues to inspire future generations to reach for the stars and the red planet, if they're not wasting their life reaching for craft ales and viral cat videos, instead. Thanks, Ray.

Wonder women of the future

In the past, "women of the future" predictions were usually hotbeds for dusting off sexist, Mad Men-like tropes of the 1950s, with men joking about how lazy their wives would get after robot maids, cooks, and butlers replaced household chores (watch a few '50s sci-fi flicks if you think we're joking). Even before a lot of the condescending misogyny was outed in the '70s, early feminist ideas found ways to sneak into the general populace during the Father Knows Best decade.

In 1950, Associated Press writer Dorothy Roe came up with a few wacky predictions that, while inspiring, didn't exactly pan out. For instance, she claimed (with science to back her up) that all women of the future would top off at six feet. Not only that, but they'd sport superheroine-esque proportions and dress like Wonder Woman, with "muscles like a truck driver" so they could compete in male sporting events and work in traditionally male jobs.

Roe may have been less-than-prescient when envisioning a future filled with massive, trucker-tanned gals, but modern women are, indeed, competing in more traditionally male sports like baseball and "prizefighting," although, sadly, not on a professional level, for the most part. But perhaps Roe's most off-the-mark prediction is that women and men of the future will cut out food altogether, eating instead only "food capsules." You need only to peek inside a Chipotle during the lunch rush to see how that didn't at all pan out.

Popular Science pops off

Throughout its 144-year history, Popular Science spent the majority of its time covering interesting topics from the world of science and technology. The long-running magazine has also, on numerous occasions, peered into the future — with limited degrees of success.

Back in 1963, Pop Sci ran a feature about "Tomorrow's Man." The two doctors that wrote it seemed to think the future human, with its adaptable body type, was ready for some major hardware upgrades. Looking like a reject from a Borg/Pulp Fiction gimp cosplay crossover, the Tomorrow Man is decked out in a cybernetic flight helmet with goggles and a breathing tube. He rides his atomic tricycle to victory over the world of common sense (and good taste), armed with his "atom chaser" and video antennas, solar light replicator (what exactly happens to the sun in this future?), atomic jet pack, and a kooky "digital computer" strapped to his side — at least that came true. To be honest, we're looking more like the Tusken Raider of tomorrow.

Even better, apparently their prediction was made before the days of Radiation is bad, mmmkay?, so the future human is decked out in atomic and gamma-powered gear. Basically, our future selves are either on the verge of species-wide cancer epidemic or about to turn into the Incredible Hulk.

Beardos from the year 2000

Ah, the Man of the Future, bastion of technology running roughshod over common sense. Sages and seers around the world have sought to envision our distant selves. As a result, the media glommed onto the futurism trend by publishing their own look at tomorrow across numerous industries, including manufacturing, farm tech, and fashion.

In 1939, Vogue tried to imagine what the future-man might look like, style-wise, running a (possibly tongue-in-cheek) conceptualization of the 21st century man. Visually vetted by designer Gilbert Rohde, the future dude decides to revolt against shaving (this actually happened). He also eschews the frustrating neck ties and bowties of his day in favor of button-less full-body jumpsuits. His hatred of pockets also knows no bounds, as Bro 2000 now rocks belt-storage — the fanny-pack of the future! To top off his ensemble, Rohde conceptualized a stylish fez with attached colander-antenna hat, used for "snatching radio out of the ether."

So, Vogue predicted a future M.C. Hammer hipsters. It could still happen!

Future farms of America?

Technology's march is dauntless and often inspiring, but absolutely terrifying to our distant ancestors. Those who came before us, toiling under a hot sun, would gaze upon the massive machine harvesters, factory farms, and genetically manipulated hybridization of the contemporary era as friggin' witchcraft. Burn them! But visualizing the progression of America's heartland definitely inspired some bizarre takes on harvesting circa 2000. Future Farmers of America this shan't be.

In 1956, Long Beach, California-based Southland magazine forecasted the farm of 2000. In its TL;DR tale of Farmer Jones and his family, the 'zine details the wild world of future farming: Happily tucked beneath their bomb (and fungus) proof solar dome, Jones and his clan tend the earth with the help of push-button computers and robot farmhands (the criminally underpaid migrant workers of the future). As Jonesy twiddles switches, these farmhands spray chlorophyll spritzes across the fields and nurture fields full of giant vegetables, not unlike the delightful GMOs of today. Best of all, each year, the harvest is fertilized with a good, clean hydrogen bombing. Absolutely delicious! Where do we sign up?

The New York Times' future fail

Conan O'Brien wasn't the first transplant to cast predictions of the future about the Big Apple. Back in 1950, the New York Times featured a piece by science editor Waldemar Kaempffert entitled "Miracles You'll See In The Next Fifty Years." After talking to a few notable scientists, ol' Kaempy set out a few wild ideas about what life in the year 2000 might look like. Fortunately, he doesn't include the flying car bit, and a few of his fifty-year miracles actually match up, such as the dominance of TV dinners and the rise of computers. Otherwise, not all of these predictions quite hit home.

Among his more appetizing concepts was a diet consisting primarily of sawdust, which would replace traditional food — except the frozen dinners, of course. Dinner would also be served exclusively on single-use paper plates. After a delightful meal of wood shavings, cleanup would also be a breeze, since everything in our $5,000 steel homes, including the furnishings, is waterproof. Just a quick hose-down and our house is spotless! Personal grooming also sounds painless, since razors have been replaced with depilatory creams. Best of all, our disposable rayon underpants are recyclable, along with our tablecloths, becoming colorful candy for the kids (seriously).

With perks like Underoos candy, weather-control devices, and personal helicopters, what's not to love about this future?

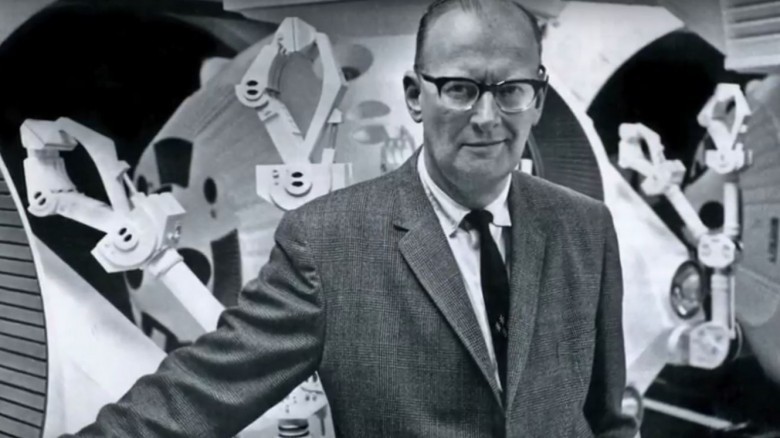

2001: a domestic odyssey

One of the most notable science fiction authors of the 20th century is, without a doubt, Arthur C. Clarke. Responsible for some of sci-fi's most inspirational cosmic moments, such as 2001: A Space Odyssey and its famously confusing film adaptation, Clarke was also, unsurprisingly, a futurist. Many of his predictions, such as a "global library" (the interweb), "personal transceiver" (cellphones), and miniaturization (microcomputers), actually came true. But even this great visionary made a few missteps.

Back in 1966, Clarke conjectured about the houses of the future, claiming that they wouldn't require any sort of connections to sewer or electric lines. Instead, they'd utilize miniaturized power sources, making our very homes themselves portable (yes, trailer parks already existed then, and that's not what he meant). These mobile homes could freely migrate from colder climes to the South, just in time for Mardi Gras, or get you to Atlantic City whenever you felt "the need for a change of scenery" or losing a few hundred bucks at the slots. Admittedly, hipsters did popularize the tiny house movement, but they aren't quite as self-contained as Clarke's idealized version. At this point, we're more in love with his future, where we do away with concrete and rid the world of one of its greatest scourges: traffic.

F.E. Smith and the sesquicentennial human

Back in 1930, English conservative politician F.E. Smith penned some curious perceptions about his not-too distant ancestors. Amazingly, denizens of the year 2000, he claimed, will be able to live drastically increased lifespans, hitting the 150 mark. Of course, such longevity will cause some serious troubles at work, including labor shortages while 20 year-old workers compete with vigorous 120-year-olds for jobs. Also, since most employees are now robots (that one sort of happened), the workplace could get pretty dull. At least this means shorter, 20 hours workweeks. Most importantly, through some crazy future-tech, we'll be able to slow the Earth's rotation, giving us 28 hours in every day. So, 20 hours of work each week and eight extra hours per day? There will be plenty of time for Smith's fox hunting and cricket playing indeed, as well as farming, which the politician suggests will become a rich person's' hobby.

Rather than watching Dr. Phil, we'll be casting our ballots through the television (nope: we don't even vote online). Wars will be conducted via remote control vehicles (okay, he gets a point for this one). Those extra minutes each day also amount to more travel time, as the wealthy of the new millennium can zip on over in their flying cars (hey, four more hours a day to invent them!) to the Sahara Desert, which has now been filled and turned into a luxury sea — because nobody lives there or anything. Not cool, Mr. Smith.