The Worst Books By Famous Authors

The creative arts can be a tricky business. Something like writing a novel is never objective, and even the most celebrated writer will have their detractors. More than four centuries after his death, there are still people who will tell you William Shakespeare is overrated, after all.

But famous authors become famous for a reason: They write great books. Or at least they write mostly great books, because even the best writer will turn out a few disappointing efforts over the course of their career. Every writer has a "worst book," though the term is relative — the worst book by one writer might be better than the best book by another. But the price of genius is constantly being compared to yourself, and once you deliver a sublime reading experience, your middling efforts are going to be judged really, really harshly.

What's interesting is the story behind these books. How does someone go from a terrific, award-winning, best-selling effort to a crash-and-burn disappointment? Where does the creative process go wrong so spectacularly? Why do writers publish books that sometimes seem objectively bad? Here's a deep dive into some of the worst books by famous authors.

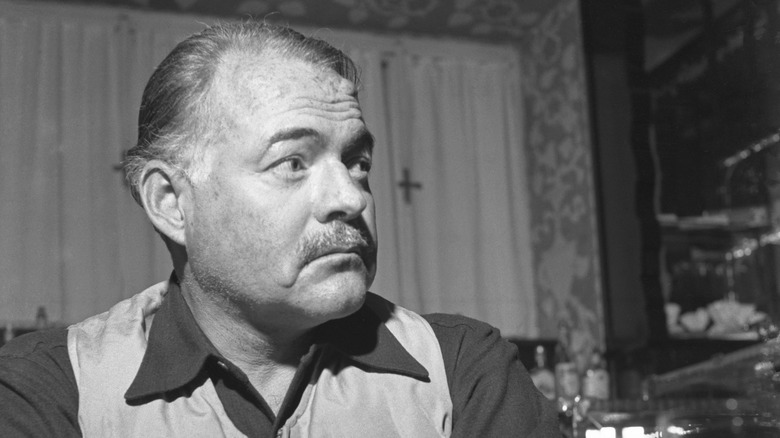

Across the River and Into the Trees: Ernest Hemingway's lowest point

When you basically reinvent American literature and change what people mean by "a novel," it changes the context of the word "worst." By 1950, Ernest Hemingway was an aging legend who hadn't published a novel in 10 years, so expectations for "Across the River and Into the Woods" were understandably incredibly high. And the book Hemingway delivered managed to disappoint on every level.

As noted by researcher Michael Hollister, one critic said the book reads "as though Hemingway got rather drunk and then talked the whole thing into a tape recorder, either for laughs or just to show off." Kirkus Reviews said, "There's crassness, lack of subtlety, needless vulgarity in the content, while the style has the erratic abruptness, elisions, and awkwardness that characterizes Hemingway at his least successful."

Biography notes that Hemingway was clearly battling depression his entire life, and themes of suicide and death are prevalent in his work. "Across the River and Into the Woods" makes this explicit — it's the story of a 50-year-old army officer with a terminal heart condition reflecting on a past love affair while sitting in a duck blind. It's also the story of a writer who wasn't handling aging very well — the novel is angry, undercooked, and unfocused. Luckily for his reputation, Hemingway recovered with 1952's "The Old Man and the Sea," which explored similar themes much more artistically, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954.

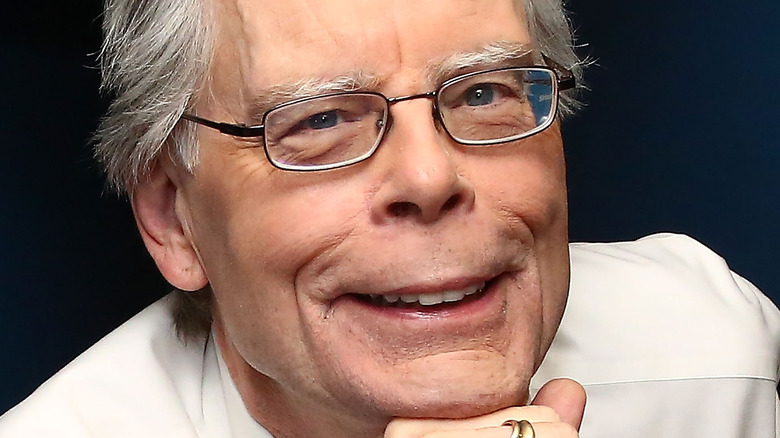

The Tommyknockers: Stephen King's coke-spiral novel

The only way to describe Stephen King's 1987 novel is "a hot mess." Although frequently described as an early novel, "The Tommyknockers" was actually King's 22nd published book if you count the ones he wrote under the pseudonym Richard Bachman. And it wasn't a fix-up of an older book — it was written fresh at the height of the first wave of King's status as a writing superstar.

And it's terrible. The story of a buried spaceship that slowly corrupts the inhabitants of a small town (and turns their appliances against them) is sloppy, confusing, and ultimately not at all scary. The Guardian calls it "confused and confusing, and far too long." Publishers Weekly wrote that the book was "consumed by the rambling prose" with "too-broad strokes [and] cartoonlike characters," noting that it was the fourth book King had published in a little over a year, obviously implying that King should perhaps slow down a bit and do more revisions.

There was a reason for both King's productivity and the decline of his writing: Cocaine. As King himself told Rolling Stone, "The Tommyknockers" was the last book he wrote while engaged in a full-tilt cocaine addiction. According to Vulture, King wrote it with "[his] heart running at a hundred and thirty beats a minute and cotton swabs stuck up [his] nose to stem the coke-induced bleeding," which sure sounds fun. The author himself freely describes it as "an awful book."

I Am Charlotte Simmons: Tom Wolfe shows his age

Tom Wolfe was 74 when he published "I Am Charlotte Simmons," so his decision to write a novel set in college whose main character was an 18-year-old woman was dubious to begin with. His decision to focus on that woman's sexuality and sexual experience at college was doubly dubious, as evidenced by the fact that the novel won the Literary Review Bad Sex Award. When one of the greatest writers of the 20th century writes a sentence like "Slither slither slither slither went the tongue," you know things are bad.

As noted by The Washington Post, part of the problem was Wolfe's revolutionary technique, which involved a journalistic approach. Wolfe disdained the concept of "write what you know" and approached his fiction with interviews, fact-checking, and deep research. This had worked for him across so many varied landscapes naturally unfamiliar to him, from LSD-dropping hippies to Wall Street titans, that it was easy for him to assume he could research his way into the mind of horny college kids in the early 2000s.

The Village Voice hilariously notes how he takes several paragraphs to define the drinking game Quarters — perhaps the most basic of all drinking games — as if assuming it would seem as exotic to his readers as it did to him. The result, as noted by The New York Times, was a novel that felt dated — Wolfe's attempts to name-check pop culture was the "Hello, fellow kids" of its time.

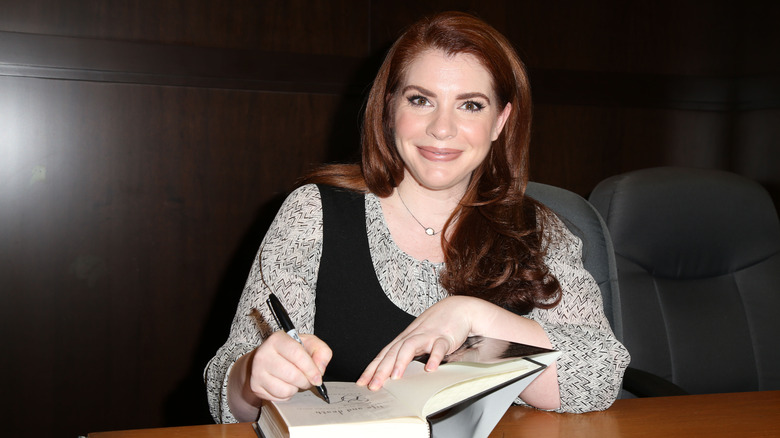

The Chemist: Even bad writers can have off-days

It's important to note that "famous authors" doesn't necessarily mean "good authors." The quality of Stephenie Meyer's prose can be argued, but the cultural impact of her "Twilight" series can't be overstated. But even if you're among the many who think those novels are not exactly examples of great writing, in the words of Billy Wilder, "sometimes it's interesting to see how bad bad writing can be."

"The Chemist" is a weird mashup of spy thriller and sexy romance. Alex is a professional torturer who excels in creating chemical cocktails that inflict excruciating pain on her subjects. Alex is also an awkward, virginal innocent who obsesses over her appearance. The Chicago Review of Books puts its finger on the main problem: The moment Meyer shifts her focus to Alex's romance with a schoolteacher she kidnaps and tortures (no, really), the story stops dead, the writing devolves from an already shaky level to grade-school kissing scenes, and her interest in the spy elements vanishes. And as The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette notes, the story is told at a comically glacial pace that surgically removes any tension or thrills.

Say what you will about "Twilight" or even Meyer's follow-up, "The Host," but those stories at least kept their focus and delivered exactly what her readers wanted. "The Chemist" reads like Meyers wanted to do something different and then lost confidence, so she quickly pivoted back to the sort of story she was more comfortable with.

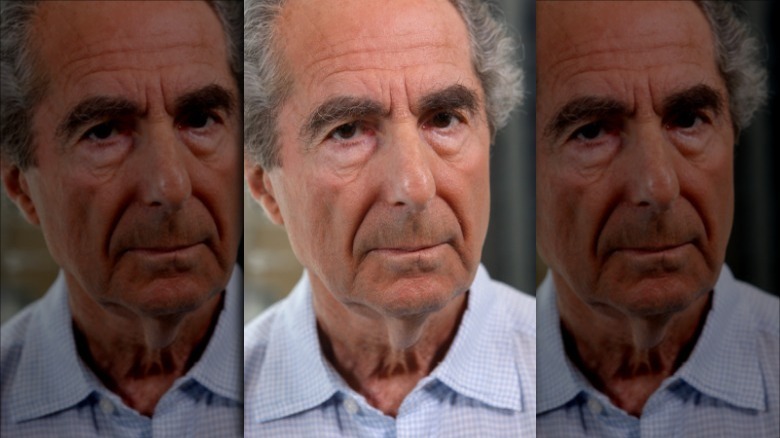

The Breast: Philip Roth goes full Philip Roth, unfortunately

The New Criterion notes that Philip Roth could be considered "very, very lucky to have died in 2018, just before #MeToo." Roth made a name for himself by writing semi-autobiographical stories about men struggling with their libidos and psychological traumas, and he achieved incredible success with that formula. Widely regarded as one of the best modern American writers, Roth's fiction can seem dated today in terms of its sexual politics.

But nothing can prepare the uninitiated for Roth's short 1972 novel "The Breast." The book starts off bad. The American Scholar includes it in its list of worst opening lines: "It began oddly" is an awkward sentence and also possibly the least compelling opening line ever written — and it gets worse from there.

It's the story of a man who mysteriously transforms into a female breast. That's it. That's the story.

Roth tries to make this seem serious with explicit callbacks to both Franz Kafka's "The Metamorphosis" (in which a man wakes up mysteriously transformed into a giant roach) and Nikolai Gogol's "The Nose" (in which a man wakes up to find his nose has mysteriously detached itself). And as Vulture reports, Roth himself thought "The Breast" was ... feminist, despite the fact that it's a story centered on a cis male whose main reaction to being transformed into a breast is how he's going to have sex with the women in his life using the nipple.

Elephants Can Remember: Christie's tragedy for all to see

Agatha Christie is a big deal. As noted by Literary Hub, she's the best-selling novelist of all time, and her books have collectively outsold every other book with the exception of the Bible and some guy named Bill Shakespeare. Christie made her name with detailed, fair-play mysteries set in country homes and other posh locales, solved by meddling old ladies or infuriatingly confident Belgian detectives, and for the most part the worst Christie novel is better than most other mysteries in the same vein.

"Elephants Can Remember" was the second-to-last novel Christie wrote. (Two of her final three novels were written in the 1940s and purposely held back for three decades.) It's an unfortunately sloppy book; author and critic Robert Ballard said of it, "Another murder-in-the-past case, with nobody able to remember anything clearly, including, alas, the author." Christie frequently forgets and changes simple details, and any hope that this is a metafictional device quickly dissipates.

As reported by The Guardian, however, there may be simple explanation: It's widely suspected that Christie suffered from Alzheimer's Disease, and researchers did a statistical analysis of "Elephants Can Remember" compared to her earlier work. They found that her vocabulary had shrunk, and her sentences had become much simpler and more repetitive in this book. In other words, it doesn't come up to Christie's standards because of illness. Fans can rejoice that her final two books were brilliant glimpses of a younger mind.

The Lair of the White Worm: Bram Stoker's illness novel

Almost everyone is familiar with Bram Stoker's most famous work, "Dracula." Almost no one is familiar with any of Stoker's other work, including his truly weird, demented, and extremely bad final published novel, "The Lair of the White Worm." The book was published in 1911, just a year before Stoker died after series of strokes. As The New Yorker points out, a lot of people are convinced Stoker had undiagnosed syphilis, which might explain how awful his final book is and why his U.K. publisher felt the need to edit it down severely and even have some anonymous person rewrite whole sections of it.

The story echoes that of "Dracula" in some ways, with a brave and resolute young man claiming his ancestral estate only to discover that an ancient, legendary monster lives nearby, posing as a human. Several characters in the novel also seem similar to those in "Dracula," which suggests that Stoker didn't put too much energy into making this one original. According to eNotes.com, Stoker's decision to reveal the identity of the monster pretty early in the story guarantees a lack of tension, and book review site Grub Street notes how convoluted and confusing the plot is, calling it a "really, really bad book."

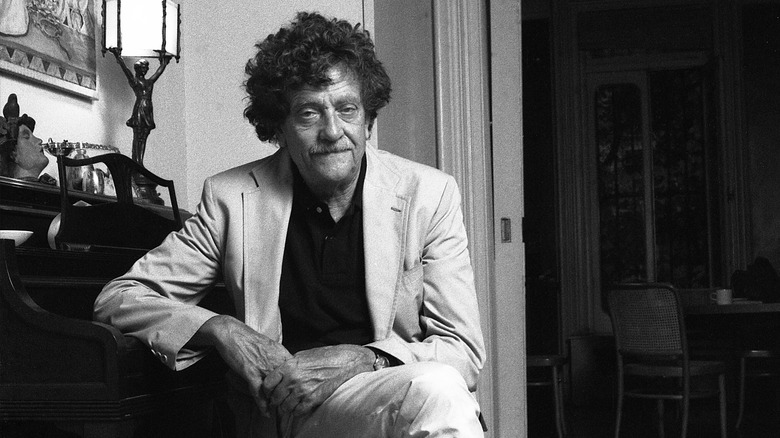

Slapstick: Kurt Vonnegut knew this book was bad

Kurt Vonnegut's 1976 novel "Slapstick, or Lonesome No More!" is very typically Vonnegut, right down to the way he seems to end every other line with "Hi ho," as a sort of throat-clearing. It's the story of two twins, Wilbur and Eliza, who become incredibly intelligent when they're in close physical contact — but their incestuous closeness repels society. The twins have a plan to end loneliness via artificial families.

The novel is ... not good. Christopher Lehmann-Haupt of The New York Times wrote, "when I finished reading 'Slapstick,' I felt as if I had just devoured a bowl of air," and Consequence describes the novel as "clumsy, outrageous, and ableist."

Most notably, Vonnegut himself thought little of the book. As reported by WNYC, in Vonnegut's nonfiction collection "Palm Sunday," he grades all of his work, and "Slapstick" received a "D." He also said "'Slapstick' may be a very bad book. I am perfectly willing to believe that. Everybody else writes lousy books, so why shouldn't I?" This is heartening, because "Slapstick," a story about incestuous, deformed twins who pretend to be mentally challenged, is indeed a lousy book.

The Casual Vacancy: This is why lanes exist, J.K. Rowling

After becoming everyone's favorite writer, J.K. Rowling has seemingly spent the last decade or so trying very hard to undo all that good work. Aside from her increasingly alarming opinions and habit of retroactively changing things in her "Harry Potter" universe, there's also the fact that she published her worst book: "The Casual Vacancy."

The New York Times didn't mince words, calling the novel "willfully banal, so depressingly clichéd that 'The Casual Vacancy' is not only disappointing — it's dull." And the Los Angeles Times wrote that "its lack of depth [is] an emblem of Rowling's inability to engage us, to invest us sufficiently in her characters, young or otherwise, to reckon with the contrivances of her fictional world."

It's clear that Rowling wanted to leave Young Adult behind and write a proper grown-up book. "The Casual Vacancy" is a murder mystery filled with sex and violence. But as Complex notes, the novel is too long and could have used a thorough edit — which might be explained by the immense fame and success Rowling brought to the table. After all, who's going to edit one of the most successful writers in the world? The end result is a novel filled with characters you don't care about and a mystery that doesn't seem all that compelling.

Cari Mora: Maybe there's a reason Harris kept writing Hannibal Lecter stories

Thomas Harris created Hannibal Lecter, one of the most famous and popular characters in literary history — and then became somewhat trapped by Lecter's popularity. After writing several poorly received books expanding Lecter's backstory, Harris finally broke away and wrote his first non-Lecter novel in years when he published "Cari Mora," the story of a beautiful, scarred Colombian woman who becomes involved with a monstrous human trafficker.

As noted by The Guardian, this book contains the phrase "sleeping in her hotness upstairs" describing Cari, which may well be one of the worst phrases ever published. The Irish Times sums up the general opinion of the novel as "a frustrating, inconsequential confection." Harris offers up a villain that ticks every bad writing bingo detail: Hans-Peter Schneider, who is hairless, murdered his parents, and likes to liquify people in a special machine when they get in his way. It's so over-the-top that it's forced some reviewers to wonder if Harris intended it to be a black comedy.

According to The New York Times, Harris is a very slow writer in part because he doesn't seem to enjoy it much, saying, "Sometimes you really have to shove and grunt and sweat" about his process. That certainly might explain this peculiarly bad novel.

Northanger Abbey: Austen's juvenilia should have remained lost

Maybe it's because it was written as a parody of a specific type of gothic novel that no one is familiar with today, or maybe it's because it's essentially a bit of juvenilia (she was just 23 when she wrote it), but the fact is inescapable: Jane Austen's first novel "Northanger Abbey" is not a good book. The story of a plain, normal girl who lets her love of ghost stories lead her to suspect terrible things are going on at the titular abbey should have been brilliant, but it suffers from a lot of amateur mistakes.

The Reader notes that many suspect the novel was originally written to entertain Jane's family around the fire at night (back in the days before television, radio, or Tik Toks). That might explain the many clumsy moments of direct address in the novel, where Austen speaks to the reader to make a point she clearly thinks is deliciously catty. But as author Peter Brown Hoffmeister writes in The Huffington Post, the characters make decisions and take actions that are impossible to understand, robbing the story of the emotional depth and searing commentary that Austen's later work would exhibit.

The Da Vinci Code: Clearing a very high bar

For all his blockbuster success, Dan Brown is often used as shorthand for "bad writer." As noted by The Atlantic, this is a man who actually published the following sentence: "A voice spoke, chillingly close. 'Do not move.' On his hands and knees, the curator froze, turning his head slowly. Only fifteen feet away, outside the sealed gate, the mountainous silhouette of his attacker stared through the iron bars.'" If we live in a universe where "fifteen feet away" and outside a sealed gate is "chillingly close," then we are truly lost, but Brown's work is filled with such ridiculousness.

"The Da Vinci Code" was the book that put Brown on the map — its success is so massive it might seem crazy to list it as his worst book, and, in fact, it's frequently cited as his best. But The Week points out the obvious: Dan Brown is not good at writing. Ranking his books very often falls back on sales and film adaptations instead of literary merit. As reported by The Guardian, his fellow authors have made the case. Author Jodi Picoult called the novel "poorly written," while Salman Rushdie called it "a novel so bad that it gives bad novels a bad name."