The Tower Of Babel Explained

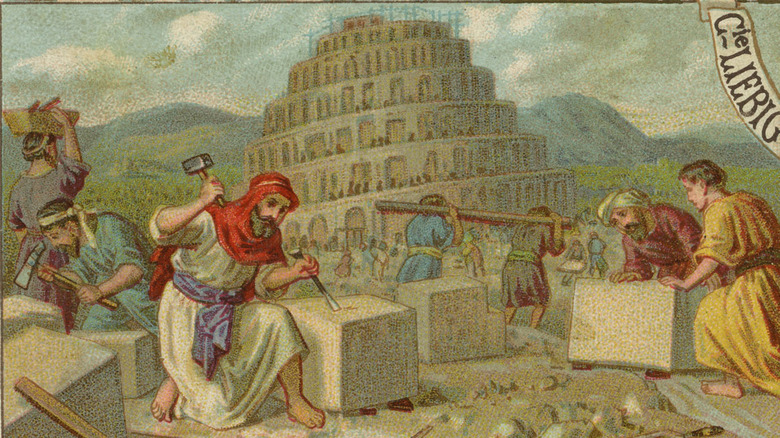

Even if you've never read the Bible, you probably know of the Tower of Babel. Described in Genesis 11:1-9, it is a structure so high and hubristic, God cursed the builders to forever speak in different languages. The story is a staple of Sunday school, a veritable goldmine for artists and poets, and one in a long line of warning stories whose lessons humanity has been somewhat spotty in following.

Today, the Tower of Babel is a metaphor for any project that aggrandizes its builders while also suggesting an inevitable fall. Big Tech has been compared to the biblical tower, and critics of the planned corporate headquarters for Amazon, designed as a whirling spire, also used the analogy.

But while the lessons and consequences of the Tower of Babel are fairly straightforward, the structure itself is a source of mystery. What was it about the tower that God was so against? Its height? Its intention? Its builders? A combination of the three?

Take look at what the Tower of Babel was, as well as what it wasn't.

Speaking of size

Genesis 11:1-9 is just 224 words. The New King James version reads:

"Now the whole earth had one language and one speech. And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar, and they dwelt there. Then they said to one another, 'Come, let us make bricks and bake them thoroughly.' They had brick for stone, and they had asphalt for mortar. And they said, 'Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower whose top is in the heavens; let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be scattered abroad over the face of the whole earth.' But the LORD came down to see the city and the tower which the sons of men had built. And the LORD said, 'Indeed the people are one and they all have one language, and this is what they begin to do; now nothing that they propose to do will be withheld from them. Come, let Us go down and there confuse their language, that they may not understand one another's speech.' So the LORD scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they ceased building the city. Therefore its name is called Babel, because there the LORD confused the language of all the earth; and from there the LORD scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth."

Although there's a lot there, there's also a lot missing.

We don't know where the Tower of Babel was

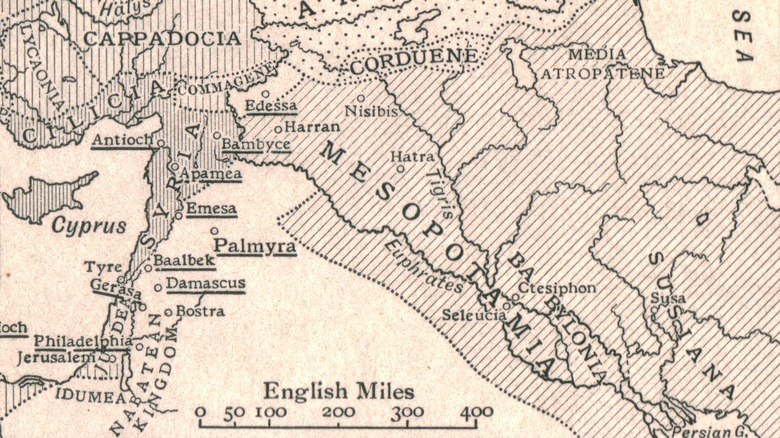

Genesis 11:1-9 mentions the place name Shinar. Skip a few passages back and Genesis 10:9-10 explains this is the land containing the cities of Babylon, Uruk, Akkad, and Kalneh. The builders of the Tower of Babel were latecomers to a place already settled.

Modern-day scholars agree that Shinar was a real place; the Jewish Encyclopedia states the name referred to a region in modern-day Iraq encompassing southern Mesopotamia (where Uruk and Akkad are) as well as a bit of its north (where Babylon is). In "Patriarchal Palestine," researcher Henry Archibald Sayce notes that it is a cognate to the well-documented land of Sumer, and that the region would eventually go by a more famous name: Babylonia.

And maddeningly, Genesis 10 and 11, while mentioning Shinar and the settlements therein, never name the city where the Tower of Babel was built. This set off a cycle of misinformation going back centuries, particularly the assumption that the admittedly similar-sounding Babel and Babylon are synonymous, which they are not. The word Babel, used to describe the city and applied only after all hell broke loose, comes from the ancient Hebrew verb balal, meaning "to mix, confuse." Babylon, clearly stated as already in existence before the whole Tower of Babel fiasco, is the Greek name for the city of Babilim.

We don't know what The Tower of Babel was

Genesis 11:1-9 describes the Tower of Babel as having a top "in the heavens," but never explicitly states that it was a temple or even to reach God; the passage says "heavens," not "Heaven." Genesis only states that the builders wanted the Tower of Babel (and city) to "make a name for ourselves." In other words, the two construction projects were essentially prestige architecture. Moreover, in "The Date of the Tower of Babel and Some Theological Implications," researcher Paul H. Seely notes that when describing the tower, biblical scribes use the Hebrew word migdal, a term meaning a lookout or defensive tower, which confuses the issue of the Tower of Babel's purpose even further.

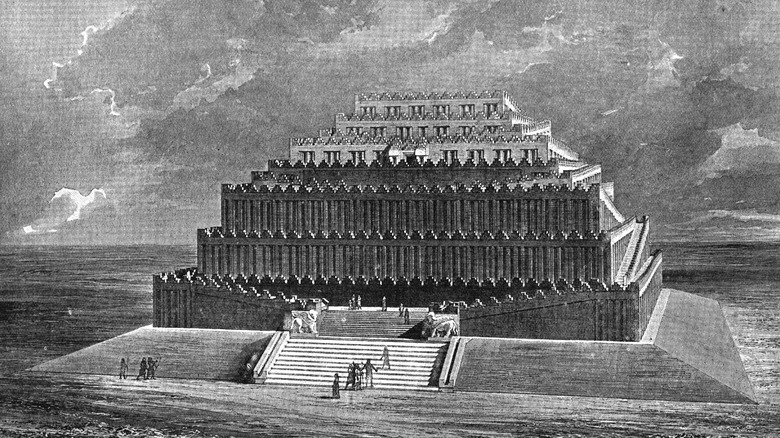

Seely, however, concedes that the wording of the passage, particularly the idiom "in the heavens," is very much in step with how ziggurats, the blockish temple type common in Mesopotamia (via ThoughtCo), were described in their day, and that a watchtower is hardly a building to bring fame and magnificence. In addressing this, he posits the idea that Hebrew scribes had no native word at the time for buildings constructed on a grand scale, and so used the one with the closest fit even if it wasn't quite right.

Alternatively, Christianity.com references the Jewish historian Josephus, who theorised (centuries after the story originated) that the Tower of Babel was made as a structure big enough to withstand another Noah and the Ark-level flood event.

We don't know when the Tower of Babel existed

A big plot hole in Genesis 11:1-9 is the lack of dates, although we do know it was after the great flood but before Abraham. In "The Date of the Tower of Babel and Some Theological Implications," researcher Paul H. Seely estimates that the Tower of Babel was around not before 3500 to 3000 B.C. based on the technologies mentioned. He notes that baked brick was not used for architecture anywhere on Earth until approximately 3000 B.C., with asphaltic mortar showing up around the same time. But he also points out that by 3500 to 3000 B.C., the "cities" of Mesopotamia were little more than large villages, with monumental architecture centuries away.

Previous chapters of Genesis are not much help either. Genesis 10:8-14 states the cities mentioned in Genesis 11:1-9 (Babylon, Uruk, Akkad, and Kalneh) were under the control of Nimrod, "a mighty hunter before the LORD" and great-grandson of Noah.

Nimrod was most definitely Type A; Genesis 10:8-14 states he also built Nineveh, Rehoboth Ir, Calah, and Resen. However, outside of the Bible, no evidence of Nimrod exists. Babylonian and other cuneiform texts do not mention him. Britannica reports that he may represent an entire people or be the biblical take on Gilgamesh. Another idea is that he is a corruption of the god Ninurta.

Finally, if Nimrod was involved in the foundation of Nineveh, which was settled by 6000 B.C., it would make him longer-lived than Methuselah by over 2000 years.

We don't know the height of the Tower of Babel

A pop culture understanding of the Tower of Babel was that it was too tall, but Genesis 11:1-9 never gives the height of the construction. That gave a lot of wiggle-room for interpretation: One medieval manuscript shows the Tower of Babel at two or three stories, while a 14th century illustration from Germany has five. By the time Pieter Brugel the Elder and Lucas van Valckenborch painted their versions in the 1500s, the top of the Tower of Babel was in the clouds.

Scholars look outside of the Bible for clues. "The Book of Jubilees," a set of religious writings sacred to the Ethiopian Jews, gets into the details of the tower's dimensions, giving a height of "5,433 cubits and 2 palms." That would be a little over 8,556 feet or 1.62 miles.

There is no way a building made of baked mud bricks and held together with asphalt can get that tall. It would be so heavy, the foundation would pulverize and the Tower of Babel would collapse before God ever got on the scene, and at that height, workers would likely suffer from altitude sickness. In fact, no building of any material can yet reach such a height — the Burj Khalifa, currently the tallest building on Earth, is "only" 2,716.5 feet tall.

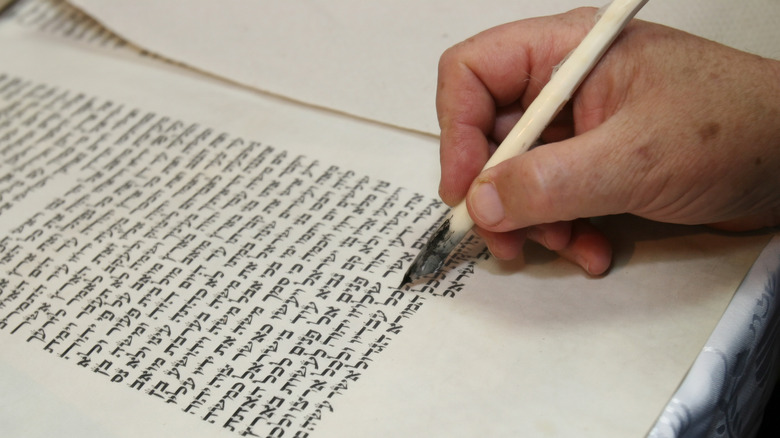

We don't know the authorship of Genesis

Knowing who wrote Genesis 11:1-9 would go a long way in giving both a timeframe and truthfulness for the events it describes. In "When was Genesis Written and Why Does it Matter? A Brief Historical Study," Peter Enns also points out that knowing who wrote Genesis, when they did so, and why might clear up what the book is trying to say.

Traditionally, the authorship of Genesis is credited to Moses, who is also said to have also written the books of Exodus, Numbers, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy while he and the future Israelites wandered in the desert. This poses questions right away, since Moses, active in the 1400s B.C. (per WorldHistory) lived long after the Tower of Babel was abandoned and, indeed, never set foot in Shinar. The Bible clearly states that, once he reached Canaan after fleeing Egypt, he never left (via Christianity.com). He must have been told the story from another, older source. This is actually suggested in Genesis 5:1, which states "This is the book of the generations of Adam." Perhaps Moses took pre-existing stories and edited them into coherent narratives.

Others take a different view. In "Prologue to History: The Yahwist as Historian in Genesis," John Van Seters place the authorship of Genesis in the 6th and 5th centuries B.C. Outside influences could have played a role in the viewpoint expressed in Genesis; in the 1400s B.C., Egypt controlled Canaan, and in the 6th and 5th centuries B.C., the land was composed of independent states. Time and context always influence a text.

God did not destroy The Tower of Babel

Masonry flying, bodies falling — long before "The Poseidon Adventure" or "Armageddon," the pop culture mythology of the Tower of Babel proves that no matter the era, everybody loves a good disaster story. Certainly the Bible is chock-full of them: from floods to plagues to the Assyrians, it isn't an unfair assessment to say the Bible is a very violent piece of literature that lurches from one catastrophe to the next. But in what may be a massive slap of reality, the Tower of Babel story is not fodder for a splatter flick. In fact, it is actually pretty vanilla by biblical standards.

It is right there — or rather, not there — in biblical black and white: The Tower of Babel is not destroyed in Genesis 11:1-9, nor does anyone die. Instead, it is clearly stated that once God confused the builders' speech, he then scattered the builders further afield so that the Tower of Babel (and the city around it) was essentially abandoned, never to be re-peopled. Moreover, not only are mortals not dying in Genesis 11, they are all but coming out of the woodwork. The rest of the chapter is dedicated to Shem and his descendants begatting several generations.

By the way, these people would still use Shem to describe themselves several centuries later — Shem is the linguistic root of the word Semite.

The Tower of Babel is an origin story

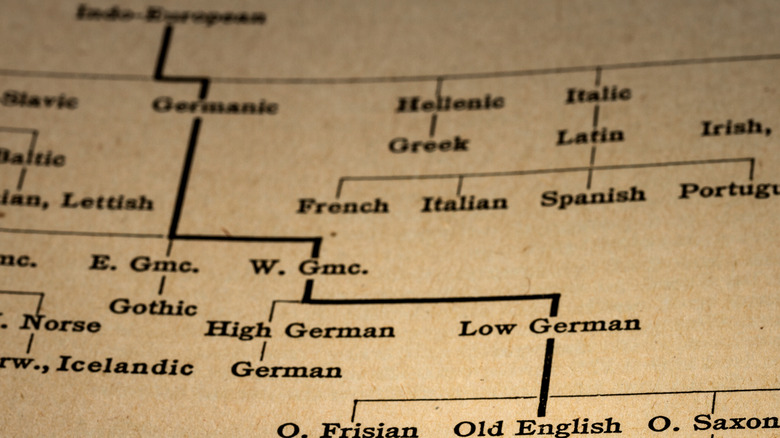

The Tower of Babel story is an etiology, a short narrative within a larger work to explain a particular thing. In this case, Genesis 11:1-9 explains how the many languages on Earth originated.

Contrary to some views, the people of the Bible — every last one of them — never spoke English, a language that did not emerge until the 5th century (via Oxford International English). But before modern linguistics, there was fierce debate over what the pre-Babel language the world was. Genesis 2:17, where God first warns Adam of the Tree of Knowledge, suggests that God and Adam spoke the same language; this Adamic speech was thought to be the single language of humanity until Babel.

Linguists and even the Bible itself don't agree with the Babel origin of languages. Researchers are confident that by 5,000 years ago, human speech had already proliferated into mutual unintelligibility. Mesopotamian peoples of the age were probably speaking early Sumerian (per Seely), but Indo-European, of which English is a variant, was already being spoken on the Eurasian steppe. Paleoamericans were speaking their own languages when they reached the Americas 13,000 years ago, as were the ancestors of the Aborigines when they settled Australia around 60,000 years ago.

As for the Bible, pre-Babel Genesis 10:5 states different languages already existed as a result of human migration.

The Tower of Babel is a warning

BibleStudyTools puts forth that the sin at Babel was two-fold. The first comes from the line "let us make a name for ourselves" in Genesis 11:4, an indication of pride or arrogance. Those are two concepts that never end well.

Gods, in general, do not like the overly-ambitious mortal. From Bellerophon and Arachne of the Greeks to Gilgamesh of the Sumerians, the concept of hubris — of mortals ascribing towards or trying to attain godly status — is a common theme in stories involving divine punishment. Even the potential of hubris is enough to get the ball rolling; while God was certainly angered by Adam and Eve eating from the Tree of Knowledge, Genesis 3:22-23 states he was far more concerned that his now self-aware creations would become like gods themselves if they ate of the Tree of Life, and threw them out of Eden accordingly.

The second, more subtle but more far-reaching reason is found in Genesis 11:4, "otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth." The people of Babel wanted to stay where they were in Shinar, which was in direct contradiction to God's order (in Genesis 9:1) to Noah and his descendants to "fill the Earth." As much as Babel's builders were reaching beyond their limits, they had also disobeyed God.

The Tower of Babel is something of a one-off

In general, God has no problem with destroying the works of humanity. The reasons for him doing so are myriad, and sometimes are as controversial as they are conjectural. But one thing that really miffs God is putting another god before him. He is jealous, after all.

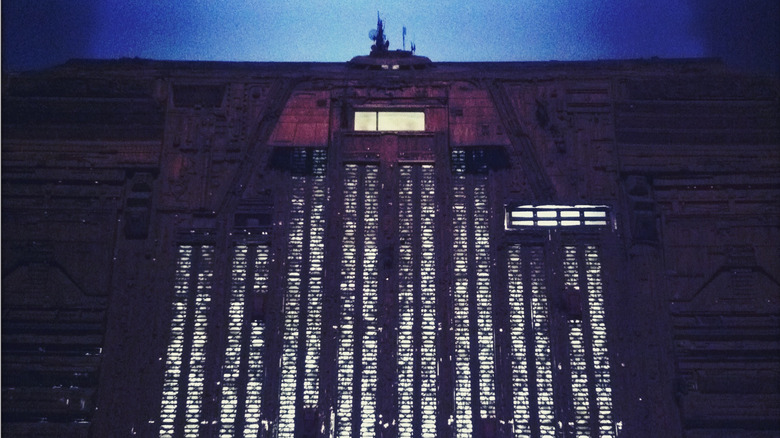

This opens up a can of worms: Even a brief look at the ancient world reveals monumental prestige architecture that had everything to do with some other god that God never touched. The Pyramids, the Parthenon, and the Temple of the Sun, each very tall, were completed (and some are even being refurbished). Moreover, the modern-day Empire State Building, Burj Khalifa, and Taipei 101 all soar into the sky and have nothing to do with religion at all. So if God had it in for the Tower of Babel for its height, there is the natural question of why there were no repeat performances on any other particularly tall building.

This is not a new question. At NeverThirsty, the answer is simply that modern-day tall buildings are not centers of false worship, and that even if humanity has turned away from God, those buildings are not representative of that. But why tall pagan buildings reached completion elsewhere is a mystery for the philosophers.

Did the Tower of Babel ever exist?

Modern scientists suspect that the iconography surrounding the Tower of Babel draws at least partially either on the famous Etemenanki, the main ziggurat of Babylon (via AncientOrigins) and dedicated to the god Marduk, or Ezida, an equally illustrious temple in the city of Borsippa dedicated to Nabu. Neither of these sanctuaries are the Tower of Babel itself, and at least one source flat-out states that in real-world terms, the Tower of Babel never existed.

That hasn't stopped comparative mythologists looking for Babel-like situations in the same timeframe to lend veracity to the idea the tower was real. While no exact parallel has yet been found, one Sumerian tale, "Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta" does have motifs that get close.

Enmerkar, the semi-legendary king of Unug Kulaba (aka the very real city Uruk, mentioned to be in Shinar) wants to make his temples more opulent, but doesn't have the gold for the job. Thus, he demands tribute from the Lord of Aratta, setting off a flurry of messengers running between the two. One messenger cannot remember all the information, so Enmerkar invented writing that everyone understands at once.

The inference is that the eye-catching luxury Enmerkar desires equates to the eye-catching height of the Tower of Babel, and instead of different languages being created, writing was.

Pop culture loves the Tower of Babel

So who cares if nobody knows what the Tower of Babel looked like or where it was? While scholars and archeologists squabble over the veracity of Genesis 11:1-9, pop culture gleefully picks up the slack, and even adds a few elements along the way.

The tower in the 1926 classic film "Metropolis" by Fritz Lang blatantly rips off the biblical story (per ArchitectureLovers.com). A gorgeous example of German Expressionism and Art Deco, "Metropolis" ups the ante by including not just a nod to Babel, but by adding the nightmare of what goes on inside it. A mad scientist defies all holy mores by ripping out and then transplanting a human soul into a machine. That tower was then yanked into the modern age by the ominous Tyrell Headquarters in "Blade Runner" and, by extension, "Blade Runner 2049." In both films, the tower is where life is made and where the decision to end that life is mandated. The aspirations to godhood are clear, as are the repercussions. 2006's "Babel" uses the reference as an analogy of globalization.

And it's not just Western pop culture that reinvents the parable; the Tower of Babel is one of the Bible's best exports. South Korea's 2019 crime drama "Tower of Babel" uses the analogy for an all-powerful business conglomerate that does anything to keep its secrets.