The Untold Truth Of The AME Church

In 2015, when Dylann Roof attended a Bible study at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church and proceeded to shoot the parishioners in attendance, the hate crime thrust into the spotlight not only America's violent history but also its oldest and most storied Black denomination (via The New York Times). The "Black Church," collectively, has, over the last century-and-a-half, become a formidable institution in American politics, along with frequently giving voice to its social conscience — and the first Black Protestant denomination in history was the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Like most Black denominations, the AME Church was founded out of discrimination, courage, and sheer necessity. The theological differences between the AME and the Methodist Episcopal Church it broke away from were basically nil; it was just that the white clergy had made it clear that black clergy and parishioners were unwelcome in their fellowship (making the AME Church the first Protestant denomination founded for racial, instead of theological, reasons). Despite those ugly beginnings, though — or, more likely, because of them — the AME has gone on to be a vital part of the American religious landscape and an instrumental force in the fight for Black civil rights. Let's take a look at its history.

What the heck is an "African Methodist Episcopal"?

If you're a bit intimidated by the denomination's name, you're not alone. The landscape of Protestant Christianity is a complicated one, and there are a lot of big words here, so let's take a sec to break them down.

First of all, and most obviously, the word "African" means that this is a denomination founded by and for Black people. Officially, the denomination welcomes people of all races, but it was founded on the interests and concerns of Black Americans (via The Christian Recorder). Again, this was out of necessity — the "white" Methodist church had failed to do its job on this and was actively antagonistic toward its Black members, which we'll get to in a second.

The "Methodist" Christian tradition was born out of the work of John Wesley, a priest ordained in the Anglican Church, in the early 18th century. Wesley was known for its strict "method" in adhering to Christian practice, hence the name (via the Online Etymology Dictionary). Methodism is known both for its strong emphasis on personal experience and its Arminian theology (which, to oversimplify things, emphasizes that Jesus died for all).

"Episcopal," meanwhile, comes from the Greek word episkokopos, meaning "overseer," or "bishop" (via Dictionary.com). Its presence in the name of a church means that the church is governed by bishops — usually bishops who can trace their ordination back to the twelve original Apostles (that is, an Apostle ordained someone, who ordained someone else, who ordained someone else ... down to the current bishops and pastors).

The violent origins of the AME

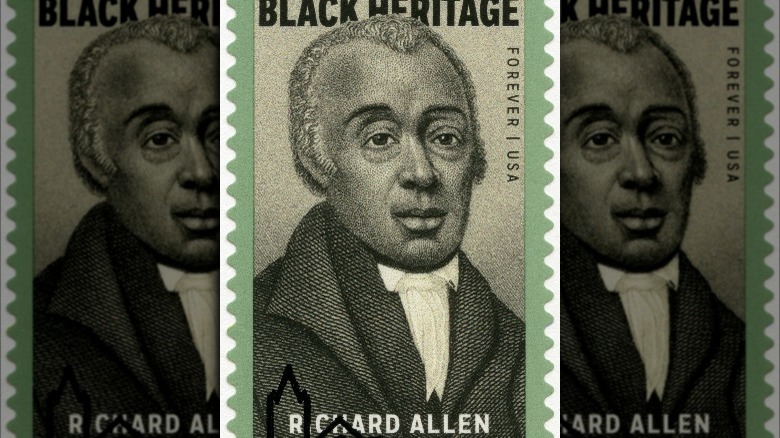

The AME Church traces its origins all the way back to 1787 Philadelphia — meaning its foundation was laid alongside the U.S. Constitution itself. The existence of the AME denomination is largely due to the efforts of one man, Rt. Rev. Richard Allen, who at the time was ordained as a pastor in the white-led Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1787, Richard and other Black parishioners were worshipping at St. George's Methodist Church in Philly — a nominally integrated church — when they were instructed to move to the balcony to avoid upsetting the sensibilities of white worshippers (via PBS). Instead, they simply walked out.

At first, Allen wasn't looking to found his own denomination, instead choosing to found a benevolency group called the Free African Society, which advocated for Black interests within the existing Methodist framework; soon, though, it became clear that efforts to keep the communion together would be fruitless. The denomination told him he could only preach to black parishioners; when Black parishioners knelt at a St. George's prayer service, ushers began forcibly pulling them to their feet to prevent them from praying with whites (via the AME's official site). At this point it was clear that there could be no peace.

The Free African Society began holding its own worship services, and began to consider its options for existence apart from the mainline Methodist church.

The AME had to sue for its right to exist

While a majority of the Free African Society's pastors eventually chose to join the Anglican-affiliated Episcopal Church, Allen and several others thought it important to maintain both their Methodist and their Black identity, and chose to found their own denomination. In 1794, Allen opened Bethel Church, which would become the first congregation of the AME. The congregation's first sermon was delivered by Bishop Francis Asbury — an absolute legend in the Methodist tradition (via The National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race). By 1810, Bethel had reached 400 members — but it didn't get there without attracting a great deal of jealousy from Philadelphia's white pastors (via the World Council of Churches).

At first, the local white pastors — who apparently didn't get the whole "Rev. Allen started his own denomination" memo — attempted to assert authority over the church (via the National Humanities Center). When they failed in that attempt, they took the congregation to court. While the judge ruled that the African Methodist Episcopal Church had a right to exist, he also ruled that it actually didn't own its own property. The white church seized Bethel's land and its building — which Allen himself had built — and sold it for a profit.

Allen, however, had the last laugh, eventually raising the money through donations to buy back the church facilities (via PBS). It wasn't the only big win the AME Church would get.

The AME has consistently been at the forefront of the fight for black civil rights

Throughout the pre–Civil War era, the AME Church was a consistent advocate for the equality and dignity of Black Americans as it spread throughout the country — mostly in northern states with large populations of free Blacks, but there were antebellum congregations in Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, Louisiana, and South Carolina as well (via the AME official site). During this time, AME congregations often served as stops in the Underground Railroad (via The Post-Star).

In the years following the Civil War, the AME Church exploded in the South, thanks to the efforts of evangelists like Theophilus G. Steward, whose sermon "I Seek My Brethren" attracted thousands of newly freed Black Christians to the denomination (via Britannica). By 1850, the AME's influence reaches all the way to the west coast, with churches opening in California.

In the post-war years, the AME Church fought hard against structural inequality as well, particularly when it came to access to education. At the height of its educational project, the AME had opened more than 2,000 schools throughout both the south and the north, including Ohio's Wilberforce University (opened in collaboration with the white Methodist Episcopal Church), the second Black college to open in the U.S (via BlackPast). The AME has been at the frontlines in the fight for quality public education as well — the "Brown" in the seminal "Brown v. Board of Education" Supreme Court Case was Oliver Brown, an AME pastor (via NPR).

The AME has expanded globally

You might expect a denomination so tied to the Black American experience to have remained in the United States, but you'd be wrong; as of 2021, the AME Church has expanded to include 20 different districts, only 13 of which are located in the U.S. Before the end of the 19th century, AME Bishop Henry Turner had helped establish the colony of Liberia (originally founded so that Black Americans who wished to return to Africa could do so), bringing African Methodism with him (via BlackPast).

By 1864, the AME Church had established its Missionary Department and sent its first missionaries to Haiti; by 1912, it had more than 100 active missionaries and foreign workers (via The National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race). According to the denomination's official site, it currently comprises 2.5 million members, in 39 countries, on five different continents. Besides North America, regions with strong AME presences include the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa, Guyana, and the United Kingdom (via Britannica).