The Unbelievable Way Jack Kerouac Wrote On The Road

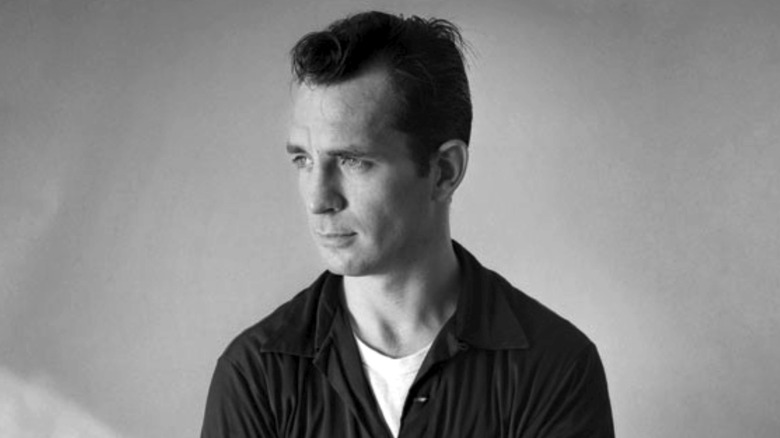

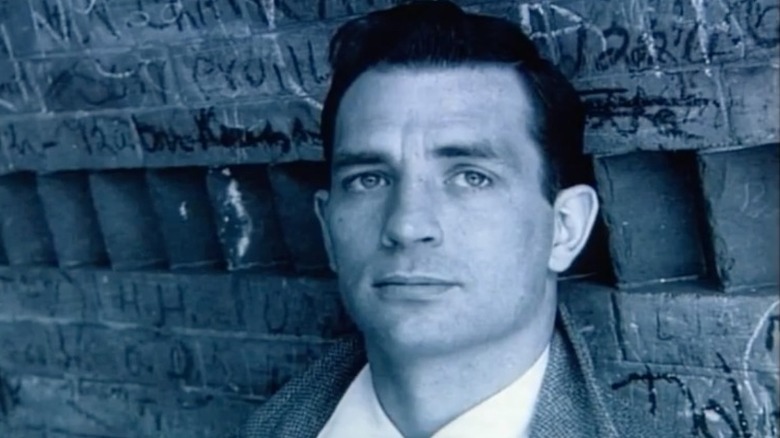

More than 50 years after his untimely death, the work of Jack Kerouac — who in his lifetime came to international prominence as the frontrunner of the "Beat Generation," alongside other prominent figures in the movement such as the poet Allen Ginsberg and novelist William S. Burroughs — continues to be discovered and discussed, admired or else derided by generations of young readers, especially those seeking an escape from conventional western society. And the vast majority of Kerouac's fame derives from the release of a single book, "On the Road," first published in 1957.

"On the Road" tells the story of Sal Paradise, an analog for Kerouac himself, alongside his friend and mentor Dean Moriarty (based on the real-life figure Neal Cassady). Written in a fresh and innovative stream-of-consciousness style that reflected the new sounds of jazz that soundtrack the book, "On the Road" represented a break from the past in more ways than one.

The book was the result of a perfect storm for Kerouac, who had lived a peripatetic life of menial jobs and extensive travel, all the time harboring aspirations to become a fresh new voice in American literature. "On the Road" was dam breaking, a perfect balance of thoughtfulness and instinct that had a seismic impact on American society. Here is how Kerouac did it.

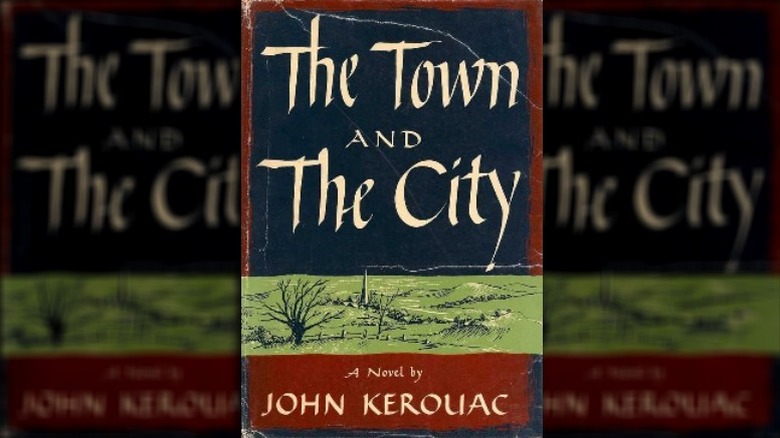

Jack Kerouac's early work is conventional

"[T]he only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes 'Awww!'"

So reads one of the most famous passages from "On the Road," one of the novel's many ecstatic, performative climaxes. But the passage is not as wild and freewheeling as it might first appear, with Jack Kerouac employing classical literary devices — anaphora, parallelism — to create the sense of tension building before a sudden release.

To account for such techniques — which permeate the otherwise disorganized and unstudied style of "On the Road" — readers can look back to Kerouac's first published novel, "The Town and the City," which was released in 1950 when Kerouac was 28 years old (per Britannica). The book is a doorstopper clocking in at nearly 500 pages long, and, like his more famous work, based on his own life. However, the novel is a dry, domestic fiction, written in imitation of earlier American novelists such as Thomas Wolfe. But while his writing was about to undergo a significant transformation, his apprenticeship in conventional prose gave him the groundwork to achieve what was to follow.

The letter that changed everything

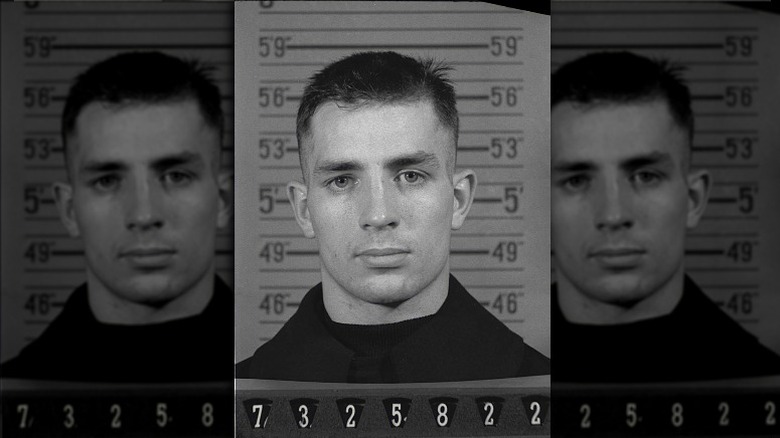

Jack Kerouac's distinctive style was greatly influenced by both jazz and the American free verse of poets like Walt Whitman, notes Britannica, but in the history of the Beat movement there is one document that academics agree changed Kerouac's writing more than anything else: a letter he received from Neal Cassady — the inspiration for Dean Moriarty in "On the Road."

According to Alta Journal, the "Joan Anderson letter," as Kerouac and Cassady came to refer to it, was written in 1950, a few years into the pair's friendship, and tells the tale of Cassady's meeting of the titular woman and his subsequent leaving of her after an eventful stay in a "flophouse" in Denver. In 16,000 words and using a singular style that Kerouac later described as "all first person, fast, mad, confessional ... all detailed" (per The TLS), Cassady wrote with shocking honesty and immediacy of the ecstatic highs and the abject "horrors" he was experiencing — and subsequently awoke in Kerouac new possibilities for American narrative prose.

Kerouac had already been working on his follow-up to "The Town and the City," envisioning a novel that would draw upon his experiences of the jazz age, of his work on the railroads, and his down-and-out travels across America. But according to Literary Hub, four months after receiving the Joan Anderson letter, Kerouac decided to shelve two years' work and start afresh — a decision that cleared the way for the legendary method of composition of "On The Road."

The dawn of "spontaneous prose"

In the wake of receiving the Joan Anderson letter, Jack Kerouac began to theorize upon a new literary method that he believed would come to reflect the preoccupations of the age. The method came to be known as "spontaneous prose" and was the hallmark of the Beat Generation's literary aesthetic. The central tenet of spontaneous prose was that writing should mimic the immediacy of lived experience; that by dispensing with planning, editing, revising, and even proper grammar and punctuation, in the belief that "first thought is best thought," as Allen Ginsberg later described it (via allenginsberg.org), a new literature could be established that better described the ecstasies and abjection of post-war America.

According to Britannica, in 1958, a year after the bombshell publication of "On the Road" made him a major literary celebrity, Kerouac published in the Evergreen Review an essay clarifying the principles of his signature style, titled "Essentials of Spontaneous Prose," which declared: "Time being of the essence in the purity of speech, sketching language is undisturbed flow from the mind of personal secret idea-words, blowing (as per jazz musician) on subject of image" (per the University of Pennsylvania). Kerouac recommended writing in an "uninhibited" state of "semi-trance" — just as he had supposedly done in the writing of "On the Road."

Jack Kerouac's dream to change American letters

The sense Jack Kerouac had of belonging to a movement, of being capable of creating his own seismic new wave in American literature, was established long before the breakout release of "On the Road." Kerouac was a prodigious and prolific writer throughout his early life, with Britannica claiming that the writer had already accumulated a body of work running to more than a million words by 1944, by which time he had cemented his friendship with his fellow Columbia University students and future Beats, William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg.

The same source claims that, like many other young literature lovers, Kerouac's childhood dream was to write the "great American novel." But after the completion of "The Town and the City" and his receiving Neal Cassidy's "Joan Anderson Letter" in December 1950, his ambition sharpened. Kerouac now believed that through spontaneous prose it was possible to cause a revolution in American letters.

As the Beats cemented their world view, which promoted openness, freedom, and immediacy in the face of societal conformity, they became in the words of the academic Graham Caveney, a "group of writers who believed they really could change the world or explore their inner souls without irony" (via The Chicago Tribune).

Jack Kerouac wrote on Benzedrine

When it comes to inspiration, it wasn't just jazz, Walt Whitman, and spiritualism that got the Beat Generation going. In fact, the Beats became famous for their "anything goes" attitude — which included their well publicized use of drugs, particularly stimulants, to get their creative juices flowing.

A commonly used drug in Beat circles in the late '40s and early '50s was Benzedrine, an over-the-counter that Brigham Young University claims was an amphetamine, with similar properties to the street drug speed, which was typically administered using an inhaler. However, Kerouac's preferred method of consuming the drug involved breaking the inhalers open and swallowing whole the Benzedrine-laced cotton inside. The dose was enough to fuel marathon writing sessions with the writer's mind racing, allowing Kerouac to write in a "semi-trance" and with, as he put it, "no pause to think of proper word but the infantile pileup of scatological buildup words till satisfaction is gained, which will turn out to be a great appending rhythm to a thought and be in accordance with Great Law of timing" (via the University of Pennsylvania).

Jack Kerouac wrote on a continuous scroll

Having established the fundamentals of "spontaneous prose" as a breathless, breakless, drug-fueled method of instantaneous composition, Jack Kerouac sought to alleviate himself further of obstacles that would slow his beatific writing sessions for "On the Road."

NPR notes that, like most other novelists of the era, Kerouac wrote using a typewriter, which, while certainly being faster than a pen, was nevertheless hindered by the carriage, which held the paper, having to be reset manually at the end of each line, and the necessity of inserting a new piece of paper into the roller each time the writer got to the end of a page.

There was little that Kerouac could do about the first hindrance, but to combat the second he came up with an ingenious solution that has become central to the legend of "On the Road's" composition. In interviews following the release of "On the Road" — including his famous interview with Steve Allen, with whom he later collaborated on an album (via YouTube) — Kerouac claimed that he had written the novel on teletype paper, rolls of which had been used by telegraph machines since the 1920s (per Britannica). However, as noted by Penguin Random House, the truth was that Kerouac taped together multiple lengths of tracing paper to form a 120-foot-long continuous scroll on which he could write uninterrupted.

Jack Kerouac's incredible memory

"The Town and the City" had been a highly fictionalized version of his early life in Lowell, Massachusetts, but by the time he was ready to write "On the Road," Jack Kerouac had made the decision to abandon fictionalization as much as possible and attempt to write an account of his own true lived experience on the road in the late 1940s. He wrote, "Renounce fiction and fear. There is nothing to do but write the truth. There is no other reason to write" (per "On The Road: The Original Scroll").

One of Kerouac's great idols was the French writer Marcel Proust, whose seven volume novel "In Search of Lost Time" dramatizes the arduous cataloguing of the memories of a lifetime. Kerouac's new apparent vision of "On the Road" as a feat of confessional recall — that would recall his experiences honestly — was inspired by Proust's work, notes The Guardian. Among his friends and acquaintances, Kerouac was known for his incredible powers of recall; as a child, he had been given the nickname "memory babe" (per Santa Monica Public Library), and his gift for remembering minute details, turns of phrase, and even whole conversations that happened years earlier came to feed into his writing practice.

Jack Kerouac wrote a draft of "On the Road" in three weeks

The now legendary marathon writing session that gave birth to Jack Kerouac's "On the Road," considered today to be a classic of 20th century American literature, took place in April 1951, according to the British Library. Armed with a 120-foot-long scroll, the fundamentals of spontaneous prose, the influence of his fellow Beats, a continuous supply of coffee, and ample doses of Benzedrine, Kerouac sat for days on at his mechanical typewriter at the home he and his wife shared in Manhattan.

Frenzied nights followed frenzied days, until Kerouac finally emerged with a completed scroll, absent of paragraph breaks: It was a chronicle of his adventures around the United States and Mexico, his reflections on the traveling life, of his relationships, and of his life-changing friendships with Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg, and other members of the Beat Generation. According to Penguin Random House, the text was 120,000 words long.

But "On The Road" wasn't as spontaneous as it appeared

"Three weeks" was Jack Kerouac's reply to Steve Allen in 1959 when asked how long it took him to write "On the Road" (via YouTube). But though the "original scroll" of "On The Road" and the three weeks it took to make it do stand up as historical fact, whether it is technically true that Kerouac can be said to have "written" the novel in that period is debatable — with many contemporary academics going as far as to say the legend of Kerouac's epic writing session is actually better described as a myth, as per NPR, for two reasons.

First, it has been well-documented that Kerouac had not just made copious notes on his travels during the late 1940s, but that he had also taken multiple attempts to write his follow up to "The Town and the City." In his essay "Fast This Time: Jack Kerouac and the Writing of 'On the Road'" (via On the Road: the Original Scroll"), Howard Cunnell argues that in attempting to write a sequel to his first novel, Kerouac wrote three "major proto-versions" of "On the Road" between 1948 and 1951, and demonstrates through Kerouac's letters to Neal Cassady how revisions began the month after the scroll was completed. The scroll would go through several major redrafts — eliminating much of the original's graphic material and replacing the real names of Kerouac's friends with pseudonyms — as Kerouac searched for a publisher and before the novel's eventual release in 1957.

"On the Road": a life-changing book

The gestation of "On the Road" was long and frustrating for Jack Kerouac, who regularly saw his work dismissed by publishers even as a greater circle of friends and admirers came to champion it as the product of a powerful new voice in 20th century American literature. Though Kerouac was already published, "The Town and the City" had sold poorly (as per the Kerouac Society), and in the years that followed, Kerouac would see his close associates William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, as well as peripheral Beat figures such as John Clellon Holmes, begin to publish works that better reflected the preoccupations of the Beat Generation movement.

Kerouac was 35 when "On the Road" was finally published in 1957. Though the critical response to the novel was mixed — "Breakfast at Tiffany's" author Truman Capote famously dismissed Kerouac's spontaneous prose style by claiming, "That's not writing, that's typing," per The New York Times) – the novel quickly attracted a loyal readership and became a bestseller in the U.S. shortly after its publication. Hot on the heels of the release of Ginsberg's long poem "Howl" in 1956 — and the subsequent obscenity trial that brought the Beats international recognition — "On the Road" cemented the Beat Generation as a genuinely fresh avant-garde literary movement and set the stage for the countercultural revolution that would follow in the 1960s.

"I read 'On the Road' in maybe 1959. It changed my life like it changed everyone else's," claimed the Nobel Prize-winning songwriter Bob Dylan (via the Bob Dylan website).

Jack Kerouac: an unwilling voice of a generation

"In the early 1950s, the nation recognized in its midst a social movement called the Beat Generation. A novel titled 'On The Road' became a bestseller, and its author, Jack Kerouac, became a celebrity. Partly because he had written a powerful and successful book, partly because he seemed to be the embodiment of this new generation."

So said Steve Allen by way of introducing Kerouac on his show in a famous interview and reading from 1959 (via YouTube). "On the Road" made Kerouac a star overnight, and he maintained his place at the vanguard of American literature with a slew of further releases including the 1958 novella "The Subterraneans," written in the style of Neal Cassady's "Joan Anderson" letter that, true to the spirit of spontaneous prose, was written in a single three-day session.

But as Kerouac became a cult figure and found himself idolized by the emerging 1960s counterculture, his life began to unravel. Kerouac was an unwilling icon, and the "King of the Beats" increasingly struggled with depression and alcoholism throughout the 1960s, notes the New Yorker. Kerouac wrote about how his fame consumed him in "Big Sur" (1962), perhaps his darkest novel. On October 21, 1969, Kerouac died of a hemorrhage, per The Los Angeles Times. He was 47.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

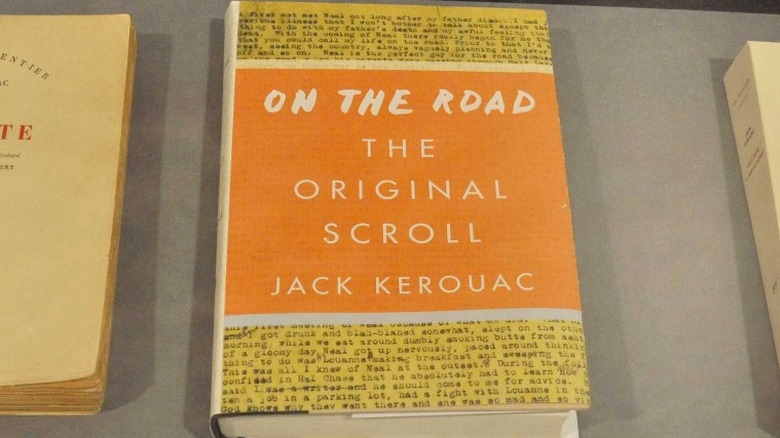

"On The Road": the Original Scroll

In the years since his untimely death, Jack Kerouac's star in the literary firmament has barely dimmed. According to literary critics Hilary Holladay and Robert Holten, editors of "What's Your Road, Man?: Critical essays on Jack Kerouac's 'On the Road,'" the novel has remained in print ever since its first publication in 1957, and has garnered a great amount of interest from academics and scholars as a pre-eminent example of avant-garde post-war American literature.

In 2001, Kerouac's 120-foot-long scroll on which he composed the first draft of "On the Road" was sold at auction for $2.43 million, a record at the time for a work of literature (per the Chicago Tribune). "On The Road: The Original Scroll," an unedited version of that document with the original names of Kerouac's friends reinstated, was published to critical acclaim in 2007. The scroll itself has had an afterlife in the 21st century as a touring attraction at universities and libraries in the U.S. and overseas, allowing Kerouac fans to see for themselves the writer's handwritten marginalia and even a page with a dog bite, per NPR.

And according to the same source, "On the Road" continues to find new readers. Kerouac's greatest novel still sells in excess of 100,000 copies a year annually in the U.S. and Canada, and countless more to would-be Beats around the world.