Beloved Famous People Who Were Despised In Their Time

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Nobody's on top forever. What people love now they may hate tomorrow. But when it comes to America, even if you hit rock bottom, your image can still get an extreme makeover, as these celebrities show.

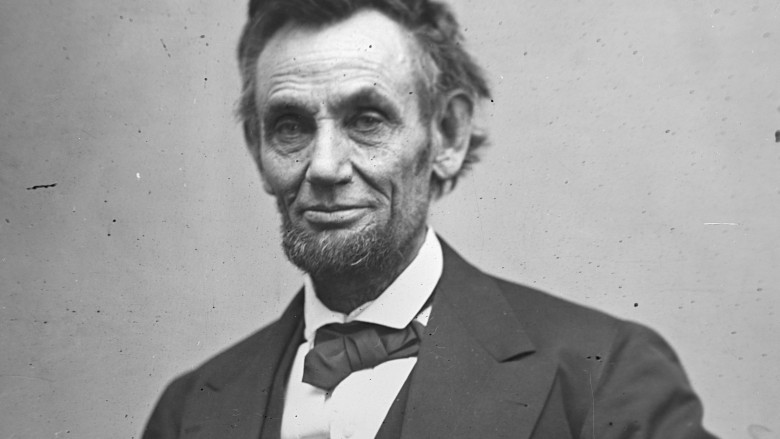

Abraham Lincoln

Historians have voted Abraham Lincoln the United States's greatest president. But a lot of Americans felt very differently when he was in office, and not just the Southerners who seceded in the Civil War.

While Lincoln won with 180 out of 303 electoral college votes, he only received 40 percent of the popular vote.The Salem Advocate, an Illinois paper, wasn't very impressed with the new president, saying, "He is no more capable of becoming a statesman, nay, even a moderate one, than the braying ass can become a noble lion."

As the war progressed, he still got terrible reviews His 1863 Gettysburg Address got panned by Pennsylvania's Patriot-News. "We pass over the silly remarks of the president," the article said. "For the credit of the nation, we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them and that they shall no more be repeated or thought of." On the 150th anniversary of this pan, the paper issued a retraction.

And it's not like the public liked him much more, if the Draft Riots of 1863 were any indication. Lincoln might have even lost the 1864 election against George McClellan, his old general, if it weren't for General William T. Sherman's march through the South.

On April 14, 1865, as the Civil War ended, John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln. This assassination started the reassessment of Lincoln. As time went on, people saw him as the Great Emancipator who saved the Union. Several states even celebrated Lincoln's Birthday. None in the South, though.

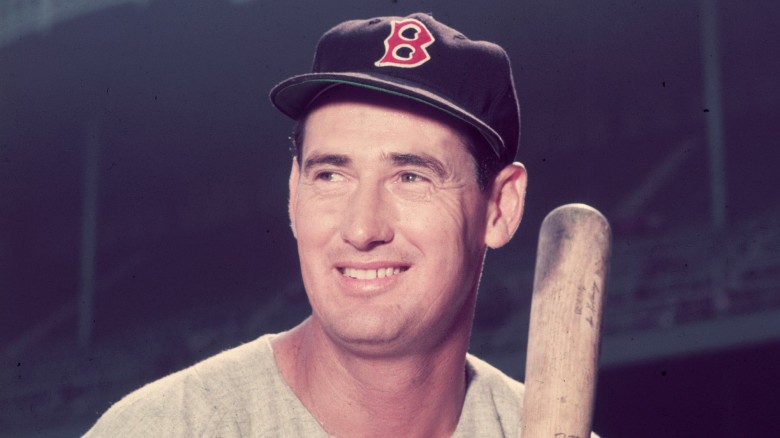

Ted Williams

"All I want out of life," Ted WIlliams once said, "is that when I walk down the street folks will say, 'There goes the greatest hitter that ever lived.'" Thanks to nearly five seasons missed due to military service as a Marine fighter pilot in World War II and Korea (he was John Glenn's wingman) the Boston Red Sox star didn't quite amass Babe Ruthian numbers, but he was the last player to hit over .400.

And The Kid won two AL MVP awards but should have won at least three more. New York Yankee Joe DiMaggio beat him out in 1941 thanks to Joltin' Joe's 56-game hitting streak. The next season, Williams won the Triple Crown but lost out to Yankee second baseman Joe Gordon, who led the league in only two categories: strikeouts and grounding into double plays. And in 1947, Williams won his second Triple Crown yet lost out to Joe DiMaggio by just one vote.

So why was Williams snubbed so many times? Because Williams was a hothead (much due to his troubled childhood in San Diego) who didn't get along with the media. "I'm the guy they love to hate," WIlliams once said. And as ESPN put it: "Joe said little to an adoring New York press and was revered. Ted said plenty to the less doting Boston scribes and was often reviled." The irony was that, as Ben Bradlee Jr.'s book The Kid details, their images were the opposite of reality, but Joe knew how to play the (media) game better.

It wasn't just the press that couldn't stand Williams. Teddy Ballgame was booed by his own fans in his early career, and vowed he would never tip his cap to the fans again.

What turned things around for Williams was when the Red Sox fined him $5,000 in 1956 for spitting at the fans. It was his third spitting incident in just one month. Both the fans and the press questioned whether they had pushed him too far. "There was a backlash against those who booed him," the Boston Globe wrote, and Williams later said, "From '56 on, I realized that people were for me."

Flash forward to the 1999 All-Star Game in Fenway Park. MLB's All-century Team was honored on the field. But the biggest star was Williams, who got introduced as "the greatest hitter that ever lived." He finally tipped his cap to Boston fans, and was then surrounded by the current All-Stars, as Williams basked in their approval. Today, while Williams is also remembered for his children having him cryogenically frozen, his overall reputation as a ballplayer and as a person has never been better.

Charlie Chaplin

The actor/writer/director/producer/editor/composer did it all when it came to the beginning of the film industry. The London, England native, born in 1889, started making American silent films in 1914 and acted in 87 pictures, most notably as The Little Tramp. But in later years, Chaplin would be mired in personal scandal thanks to his predilection for much younger women. At 29, he married Mildred Harris, 16, because he thought he had impregnated her. (It turned out to be a false alarm.) After a bitter divorce, at age 35, he married another 16-year-old, Lita Grey, whom he did impregnate. They had two children together, and he had another bitter divorce. His third wife, Paulette Goddard, was 22 and he was 44 when they first met, but he thought she was 17. They had a friendly divorce, a change for him.

The scandal that hurt him the most, though, was Joan Barry, 22 when he was 53. She accused him of fathering her child, and the federal government also went after him for violations of the Mann Act. In the meantime, he had married Oona O'Neill, Eugene O'Neill's daughter (she was 18 to his 54), the woman he would be with for the rest of his life.

After years in the courts, he was exonerated of the Mann Act charges, but a jury ruled that he was the father of Barry's child. Blood tests showed it was not possible, but the sex scandal had made him look like a dirty old man.

Chaplin also got in hot water during World War II, when he called the Russians "comrades," said that Stalin's purges were "a wonderful thing," and claimed, "The only people who object to communism and who use it as a bugaboo are the Nazi agents in this country." Then his film Monsieur Verdoux, about a serial killer, indicted capitalism at the same time the House Un-American Activities Committee was investigating him.

When Chaplin visited England in 1952 during the height of the McCarthy era, the United States revoked his visa (Chaplin had never become a US citizen despite staying in America for 40 years), and Attorney General James McGranery said Chaplin would not be allowed back in the country due to "grave moral charges" unless he could "prove his worth" to the country. Chaplin declined, moved to Switzerland, and reportedly said he "wouldn't go back [to the US even] if Jesus Christ were president." He didn't visit the US until 1972, when he was honored first at Lincoln Center, and then at the Academy Awards ceremony, where he received an honorary Oscar and multiple standing ovations.

George Steinbrenner

George Steinbrenner led a group that bought the New York Yankees from CBS in 1973 for just $10 million. Steinbrenner told the press, "We plan absentee ownership as far as running the Yankees is concerned." The 42-year-old claimed, "We're not going to pretend we're something we aren't. I'll stick to building ships."

So much for that. Just four months later, team president Mike Burke was out, and Steinbrenner was The Boss, micromanaging the team. George brought the Yankees back to prominence, starting by signing Jim "Catfish" Hunter, the MLB's first free agent, in 1974 (even though Steinbrenner was supposed to be suspended from baseball during that time for illegal contributions to the Nixon campaign.) Then he hired Billy Martin as manager for the first of five times in 1975. A year later, the Yankees made it into the World Series, their first such appearance since 1964.

Steinbrenner then wooed and signed slugger Reggie Jackson before the 1977 season, with Jackson comparing him admiringly to a guy "trying to hustle a girl in a bar." Number 44 would carry the team to win that year's World Series, with three homers in Game 6. The Boss's team continued their postseason run, winning again in 1978 and making it to the postseason in 1980 and the World Series in 1981.

But Steinbrenner's meddling caught up with him, starting with him having Mr. October benched in the 1981 World Series and not re-signing Jackson after the season. Reggie returned with the California Angels the following spring and hit a home run off his old teammate Ron Guidry, with Yankee fans giving him a curtain call. First they chanted "Reg-gie, Reg-gie," and then they did a new chant: "Steinbrenner sucks."

That anti-Steinbrenner sentiment among fans grew as the team languished in mediocrity in the 1980s, finally hitting last place in 1990. That was the year where MLB Commissioner Fay Vincent banned The Boss from baseball for life. Steinbrenner had paid a Bronx gambler named Howie Spira $40,000 to dig up dirt against Dave Winfield, once one of his prime signings. As word got out at Yankee Stadium that Steinbrenner was banned, fans happily chanted, "Goodbye, George."

That lifetime ban only lasted until 1993. In the meantime, Gene Michael took over the team as general manager, and without Steinbrenner's meddling, he was able to build the next Yankees dynasty. Nurturing a young Bernie Williams, and drafting, signing, and developing players like Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Andy Pettitte, and Jorge Posada.

The Yankees winning four World Series titles from 1996 to 2001 helped soften fans on Steinbrenner. And he himself had softened since the second suspension, with more sentiment than bluster. So in 2004, when Yankee fans spotted him on Opening Day at Yankee Stadium doing an interview with sportscaster Warner Wolf, they chanted "Thank you, George" and brought him to tears. By the time of his 2010 passing, Steinbrenner was a beloved figure in Yankeeland.

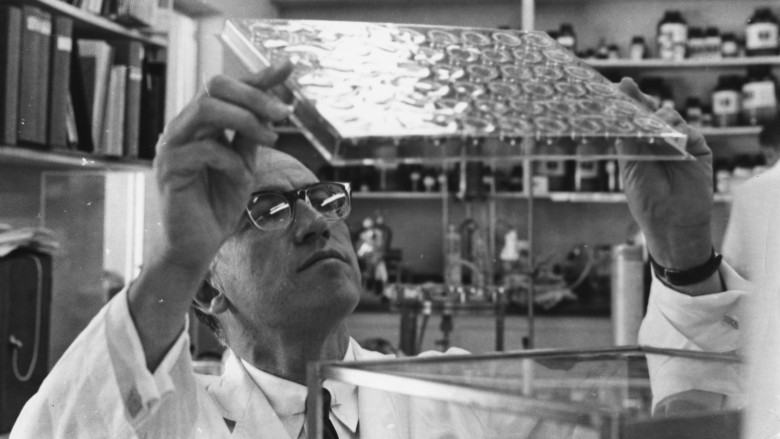

Jonas Salk

Polio was once a very feared disease, spreading terror because it showed up suddenly, leaving its victims paralyzed or even dead. As the Centers for Disease Control notes, "From the late 1940s to the early 1950s, polio crippled around 35,000 people each year in the United States alone." So after Dr. Jonas Salk developed the first successful vaccine to eradicate the disease, he rightfully became an American hero and is still remembered fondly today, especially since the US has been polio-free since 1979.

But whether it was jealousy, sour grapes, actual grievances, or the 1950s version of haters gonna hate, his fellow scientists had issues with Salk. He never won the Nobel Prize, in an era when controversial choices like Antonio Caetano de Abreu Freire Egas Moniz won for his work on developing the prefrontal lobotomy.

According to Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs's book Jonas Salk: A Life, people who worked with Salk resented what they felt was him not giving them enough credit and further resented his love of publicity. He was denied membership in the prestigious National Academy of Sciences. Albert Sabin, who developed the oral polio vaccine using a weakened virus, called Salk a "kitchen chemist," sniping: "He never had an original idea in his life" and "you could go into the kitchen and do what he did."

Lorraine Friedman, Salk's secretary, told Jacobs her boss " wasn't looking for fame" and "it cost him an awful lot personally. Many in the scientific community just didn't believe he was the innocent he claimed to be." She said that Salk even once said to her regarding his discovery, "I wish this had never happened to me."

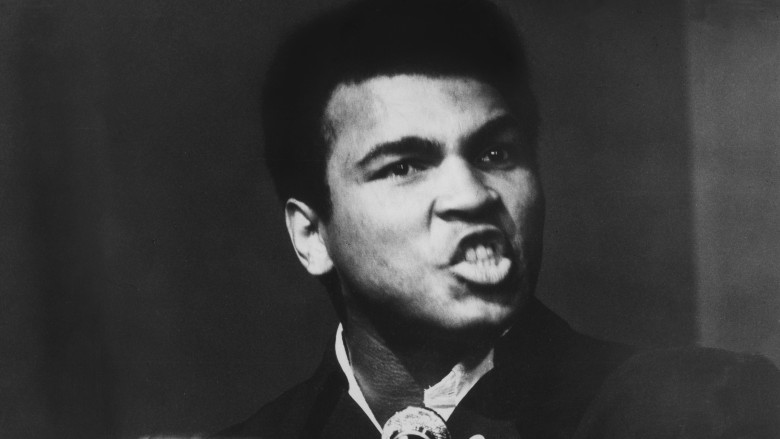

Muhammad Ali

When Muhammad Ali died in 2016, there was such a huge outpouring of love for him, it is hard to believe that the sports legend was once hated. But that is indeed the case, starting from his fight with Sonny Liston in 1964, when sportswriters didn't like the fighter, then known as Cassius Clay. Then the brash boxer with the big mouth beat Liston and proclaimed he was "The Greatest." The next day, Clay gave a press conference with Malcolm X and made public his connections with the Nation of Islam. Ali referred to his name Cassius Clay as his "slave name," asking to be called Cassius X. Elijah Muhammed then gave him the Muhammad Ali name on March 6, and reporters refused to call him by it.

Then on March 9, 1966, his military status was changed to 1A, which made him eligible for the draft. He said, "I ain't got no quarrel with them Vietcong." On April 28, 1967, after he received a draft notice, he showed up at a military induction center in Houston and refused to be inducted and take the oath, citing his Black Muslim religion.

Reaction was swift. Not only did Ali get arrested for draft evasion—he was convicted that June and appealed—but New York and the rest of the states that allowed boxing stripped him of his boxing license. Ali missed three prime years of his career until 1970, when he finally got to box again against Jerry Quarry after Atlanta restored his boxing license.

The next year, not only did Ali face Joe Frazier in the fight of the century, but he won his case against the federal government over his draft evasion conviction. Yet many Americans chose to root for Frazier over Ali, leading Ali to cynically remark, "Any black person who's for Joe Frazier is a traitor. The only people rooting for Joe Frazier are white people in suits, Alabama sheriffs and members of the Ku Klux Klan. I'm fighting for the little man in the ghetto." Harsh.

So what turned it around for Ali and made him a beloved international icon? A combination of things. As the Vietnam War went on and finally ended, his stance looked more courageous, and what once seemed like self-aggrandizing behavior looked downright noble, due in part to the real-life consequences Ali suffered. And as time went on, people could look more at Ali as a great boxer, especially after he showed heavyweight championship dominance again. But the biggest reason might be him getting Parkinson Disease, and the classy way he conducted himself. As one writer put it, Ali "transformed himself into a living monument to the global struggle for tolerance and dignity."

Frank Sinatra

Sinatra had two falls from grace. The first was during World War II, when he was entertaining bobby soxers at the Paramount Theater while young men his age were storming the beaches of Normandy or jumping out of airplanes in the Pacific.

After filling out draft forms in 1943 saying, among other things, that he was "neurotic" and "afraid to be in crowds" (really?), Sinatra was declared ineligible for the draft due to a busted eardrum, malnutrition, and "emotional instability," according to FBI files from the time. Historian William Manchester once said, albeit with a little hyperbole, that Sinatra was ”the most hated man of World War II" because the service members' wives and girlfriends were listening to Sinatra while they were overseas.

But Sinatra's career went on, and he was still wildly successful until the end of the decade, when things started to sour. Back then, he was the '40s equivalent of a boy band, and his female fans had outgrown him. Music styles had changed, too. He had fallen in love with Ava Gardner and divorced his first wife Nancy in 1951 to be with her. He had lost his movie contract with MGM. He owed the IRS over $100,000 and couldn't even afford a press agent.

What turned it around for Sinatra and ignited his career again was his ultimately Oscar-winning role as Maggio in From Here to Eternity. As the story went (a story that made it into The Godfather), Sinatra's mob connections got him the role after cutting off a horse's head in putting it in the mogul's bed. The real story: Sinatra lobbied for the role with telegrams, not mobsters, and Ava Gardner leaned on Harry Cohn's wife to give Sinatra the role.

After his emotional performance in the World War II movie, wearing military attire he never did in real life, Sinatra's career came back in a huge way with more acting roles and some of the best music of his career, even if his marriage to Gardner didn't survive.