Secret Codes We Still Haven't Cracked

Serial killers! Secret spies! Pots of gold! When it comes to the mysterious world of breaking secret codes, anything and everything is possible. Whether it's a cryptic confession or the last remnants of a dead civilization, a map to buried treasure or a secret message from the front lines, there's nothing more tempting than a supposedly unsolvable puzzle.

With that kind of allure, you'd think it was just a matter of time before every code was cracked and every cipher solved. And yet we've uncovered a collection of cryptographs that remain unbroken, frozen in amber as decades or centuries pass by. FBI agents, online sleuths and even super computers have taken their turns, dedicating years to these unbreakable ciphers, and yet they remain unresolved. So if you've got a knack for cracking secret codes, and an extraordinary amount of free time, buckle up, because solving just one of these will make you the most famous code cracker of all time.

Somerton Man's body leaves more questions than answers

It's the most famous mystery in Australian history. In 1948 a man was found dead on a beach, with no ID and the tags on his clothes removed. An autopsy proved inconclusive, but the coroner believed the man had been poisoned. The only clue was a note tucked into his watch pocket, reading "tamám shud."

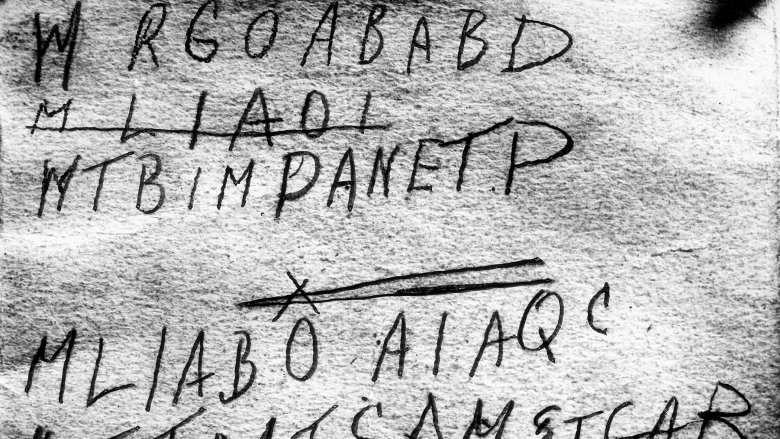

After some digging, investigators found that the phrase was torn from a rare book of 12th-century poems, and roughly translated to "finished." Weeks later a complete stranger found the book in the back of his car, seemingly tossed in without his knowledge. A complicated code was written on the last page, along with the phone number of a local nurse, who claimed not to know the deceased, even though she nearly fainted when shown a plaster cast of his face. And, just to further complicate matters, she admitted to giving a copy of the exact same book to a man named Alfred Boxall, who was still very much alive at the time.

Analysis of the code has shown it likely to be an acrostic, a type of word puzzle in which certain letters in each line form a message, but no one has been able to crack it. As for the dead man, rumors have swirled for decades that he was a spy caught in a doomed love affair. Perhaps the code is the key to finally solving this mystery, which means it may never be solved.

The Blitz ciphers look like a code from Middle-earth

The story of the Blitz Ciphers begins during the height of World War II, when a whole lot of bombs damaged a cellar in East London, unearthing a stack of papers that looked like they'd arrived fresh from Middle-earth. The family that found them didn't fully understand what they'd discovered and just stored them away, passing them down from one generation to another. They wouldn't go public until 2011, when their owner decided it was finally time to solve this bit of family folklore.

Written in an ornate style, possibly by quill, and full of odd symbols and cryptic codes, the papers are a cryptographer's dream come true. Thanks to the work of researchers at ciphermysteries.com, it's been established that there are two different forms of handwriting in the documents, one of presentation, and the other of annotation. The presentation hand lays out the bulk of the text, and the annotation hand covers what seem to be expository footnotes. Other than that, attempts to decode it have proved fruitless, the author's secrets seemingly lost to the ages. Was it a message between 19th-century Freemasons? An Elizabethan secret society's slam book? A Hobbit complaining about the food in London? Solve it and let us know.

The D'Agapeyeff cipher is the accidentally unbreakable code

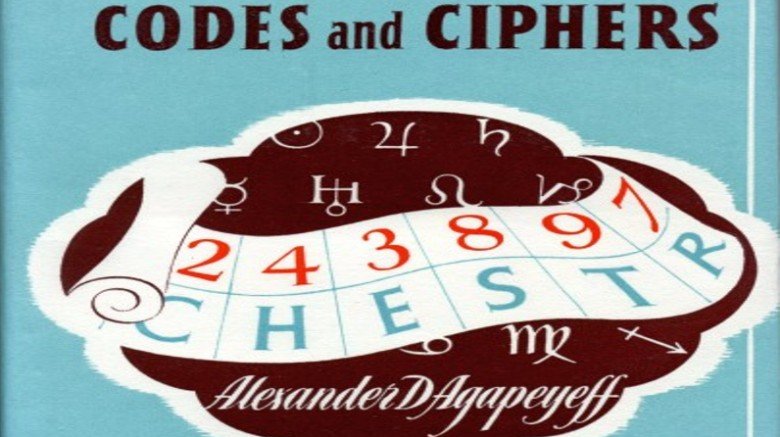

The frustration cryptographers have with the D'Agapeyeff Cipher is not that it's remained unsolved for nearly eight decades. It's that a cipher unsolved for eight decades was never meant to be all that hard to solve in the first place. It's one thing to be bested by the best, but to be stumped time and time again by a man who never meant to stump them has made this perhaps the most frustrating secret code in human history.

The story of the D'Agapeyeff Cipher starts in 1939, with the book Codes and Ciphers, written by Alexander d'Agapeyeff. D'Agapeyeff wasn't a cryptographer, per se, but just a guy looking to get some books published. His previous effort had been about cartography, for instance.

Codes and Ciphers was primarily a book on the history of cryptology, but in an effort to help the layman get a feel for the form, he included a puzzle of his own on the very last page. It was meant to be a diverting challenge, but an eminently solvable one, and yet the cipher has somehow remained unbroken for the better part of a century. And just to add insult to injury, D'Agapeyeff himself admitted he forgot how he created the darn thing, so count him among the many to be thwarted by this infuriating cipher.

This D-Day pigeon code may have cost lives

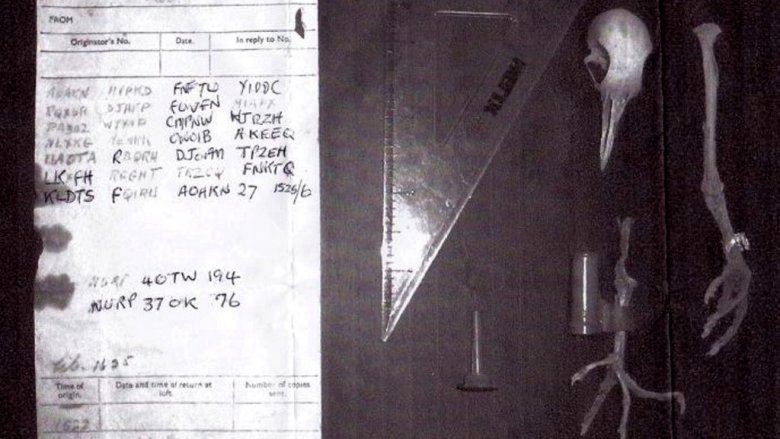

Most people don't expect to find war secrets when cleaning a dead animal out of their chimney, but for David Martin, disposing of some pigeon bones led to one of the greatest mysteries in cryptology history. The year was 1982, and Mr. Martin was digging out the deceased bird when he noticed a red canister still affixed to its leg. Inside it he found an uncrackable code that many now assume to be sent from the biggest battle in World War II history.

During the height of the war, radios were too easy for the enemy to eavesdrop on, so war pigeons were put to work, delivering top-secret message from the front line. The pigeon unearthed by Mr. Martin was labeled 40TW194, and due to the message's contents and proximity to both the beaches of Normandy and the code breaking offices of Alan Turing, many assume it was a key message relating to D-Day.

Unfortunately, 40TW194 would never complete its mission, and because of the vital nature of these plucky pigeons, lives may have indeed been lost. Sadly, we don't know for sure because the message, labeled as headed to "X02," and signed by a "Sjt W Stot," has remained unbroken, even by the very government that sent it.

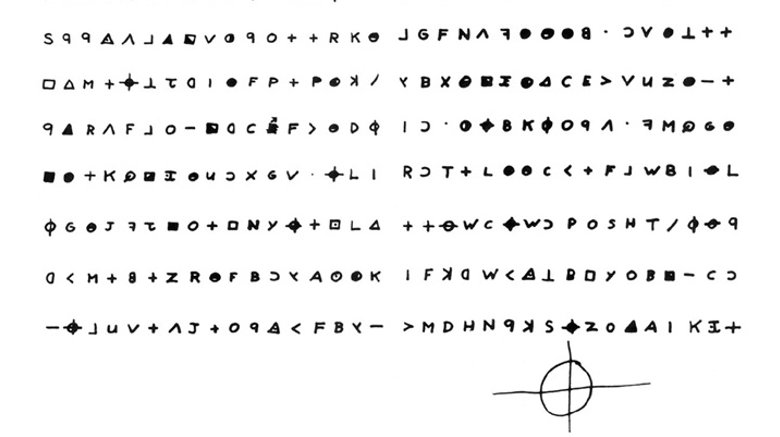

The Zodiac Killer 340 cipher outlives the killer who made it

In November 1969, the San Francisco Chronicle received an unusual care package, stuffed with a humorous greeting card, the bloodstained shirt of a dead man, and a certain cipher that's remained unsolved to this day. The package was sent by the Zodiac Killer, one of the most notorious criminals in American history. Little did anyone know at the time that his 340 Cipher would become the Holy Grail of cryptology, long after his killing spree concluded.

While the serial killer's first code, sent months before, was cracked by a school teacher and his wife in a matter of hours, his second has puzzled pros, amateur sleuths, and even sophisticated artificial-intelligence software programs such as CARMEL, for decades.

Long considered a way to make a name in the cryptology community, countless code breakers have claimed to crack it, only to have their work called into question. The first, and biggest, is Robert Graysmith, who insisted in his seminal book Zodiac that he'd solved the cipher. The FBI took one look at his sloppy work and told him to stick to his day job. In the end the cipher would take its place alongside the Zodiac killer's real identity, a mystery for the ages.

The FBI wants you to solve the Ricky McCormick notes

In 1999, at 41 years old, nobody seemed to know or care about Ricky McCormick. By the time his body was found in the middle of a Missouri cornfield without so much as a single call reporting him missing, it had decomposed to the point that his fingerprints just up and fell off. It was gross.

Even with all the forensic science the feds could provide, authorities could never figure out what had happened to poor Ricky. The medical examiner checked for gunshots and stab wounds, but couldn't find any. The cadaver's head had decayed into such a pulpy mess, no one could be sure if it suffered any trauma. Heck, no one could even decide if this guy was killed or died of natural causes or what.

The only thing close to a clue was a few crumpled notes in his pockets, covered in oddly cropped capital letters, occasionally bordered off in speech bubble–like shapes or in parentheses. Maybe they were video game passwords, maybe they were personal notes oddly encrypted for his own reasons. Nobody knows. Without other examples of this sort of writing to build on, there wasn't much to work with. That's why the FBI has asked you – yes, you — to solve this case. Or anyone else who might have any idea what the heck happened here. So far, no one's been able to crack it. But that's before you were on the case. Good luck.

Was the Paul Emanuel Rubin cipher the ramblings of a madman or super spy?

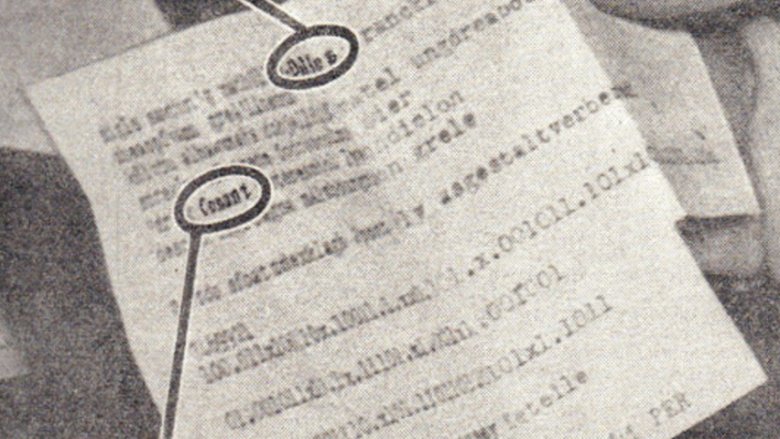

To the outside world, Paul Rubin was a typical 18-year-old New York University student, but people aren't always what they seem. On January 20, 1953, he was found near Philadelphia International Airport, deceased, apparently by way of a cyanide capsule.

He had a number of unusual things on him at the time of his death, including a picture of a Nazi plane, a plastic cylinder containing a fuse, and the casing of a spent .38-caliber bullet. But the thing that most struck the investigators was a typewritten cipher taped to his stomach, with two decipherable words, "Dulles" and "Conant." According to the Schenectady Gazette, "It was assumed the names referred to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and James Bryant Conant, U.S. high commissioner in West Germany."

While the parents of the student said he had developed a hobby of sending coded letters to friends, authorities weren't sure if they were dealing with a case of mental illness or espionage. Cracking the cipher's code was seen as the key to the case, but it remains unbroken, its secrets lost along with the life of the young man who had it.

Even America's Most Wanted couldn't solve the Scorpion Letters

It's one thing to taunt the FBI, but it takes some real cojones to come for John Walsh, the longtime host of America's Most Wanted. This is a guy who can make you famous, or infamous, overnight. For over 25 seasons he used his bully pulpit to put the heat on America's bad guys, but back in 1991, a criminal turned the tables and put the heat on him.

That was the year Walsh started getting unusual letters from someone calling themselves "Scorpion," who claimed to have committed 23 crimes, including robberies and murders. Within those letters, which would continue coming for years, were a series of codes and ciphers that have never been broken.

Due to a similarity in style, some have claimed that the letters were from the Zodiac Killer himself, while others merely think he was the inspiration. Whatever the case may be, even the biggest crimebuster in TV history failed to take this guy down ... so far.

Is the Rayburn Cryptogram a hoax or a confession?

On February 2, 2004, out-of-work internet technician David Rayburn snapped. Seemingly out of nowhere, Rayburn grabbed a hammer and beat his wife, Linda, to death, along with her son, Michael, before taking his own life. Even with a suicide note, no one could answer the key question. Why?

Two years would pass by the time cryptologist Bruce Schneier received an email, supposedly from a friend of Rayburn's daughter, with an intriguing clue. Jenn Berry had discovered the bodies of her family members that day, and according to the email, she'd also come across a handwritten cryptogram "utilizing letters, numbers and symbols from a computer keyboard." Now, Schneier admits he has no way of proving the email's author was telling the truth. Still, there's no denying that the cryptogram is real, and real confusing.

While armchair sleuths have puzzled over its secrets for a decade, amassing a treasure trove of guesses, theories, and snarky comments on Schneier's blog, no one has been able to crack the thing. Is it a killer's confession? A hoax? The incoherent ramblings of a man who'd seen one too many movies? At least for now, the secrets of the cipher remain hidden, along with the motive of this family man turned killer.

Could the Rongorongo script solve the mysteries of Easter Island?

Easter Island is famous for its secrets. One of the most remote islands in the world, it hosted a thriving civilization for centuries before disappearing into the ash heap of history. What remains, famously, are cultural artifacts that have captured the imagination, most prominently the giant heads that pepper the island.

But those aren't the only relics from a bygone era. In 1868, 26 wooden tablets were discovered by a Roman Catholic friar, containing glyphs depicting animals unknown to the region. The meaning of the symbols has never been deciphered, but some believe they could offer clues of what caused the Old Rapa Nui civilization's collapse.

The original etchings are carved on irregularly shaped wooden tablets, supposedly by obsidian flakes or small shark teeth. They depict a variety of images and symbols, including humans, animals, plants, and geometric forms. Some have estimated them to date back to the 13th century, when the forests of the island were originally cleared. Sadly, because of the limited number of glyphs and a lack of understanding of the Rapa Nui language, there has been little luck breaking this code. Perhaps some secrets are best left in the mists of time.

Follow the Beale cipher to a pot of gold

The story behind this secret code spans nearly 200 years. Robert Morriss, the owner of the Washington Hotel in Lynchburg, Virginia, vividly recalled the day he was visited by treasure hunter Thomas Jefferson Beale back in 1820. He described him as "tall, dark, and swarthy," "extremely popular, especially with the ladies," and "the handsomest man" he had ever seen.

Beale left as mysteriously as he'd arrived, which surely must have broken the heart of the clearly infatuated Morriss. Two years later, the beautiful man returned, left behind a mysterious locked box, and disappeared again, this time for good. Twenty-three years after that, assuming the gorgeous stranger was probably dead, Morriss opened the box and found a plain English letter and three encoded documents leading to a treasure now assumed to be worth around $65 million.

Morriss himself puzzled over the cryptic document for the remainder of his life, but ultimately failed to find answers. A friend, to whom Morriss had confided his story, published a pamphlet with the encoded documents in it, hoping someone could solve the riddle. This same friend also managed to decode one of the documents, realizing the substitution cipher worked with the Declaration of Independence. The pamphlet in question was published in 1885, but to this day, the other two documents and the location of the treasure remain unsolved. Why, you ask? It might all be one big joke, but all the very funny jokesters are dead now, so maybe we'll never know.