Evel Knievel: Facts About The Daredevil's Wild Life

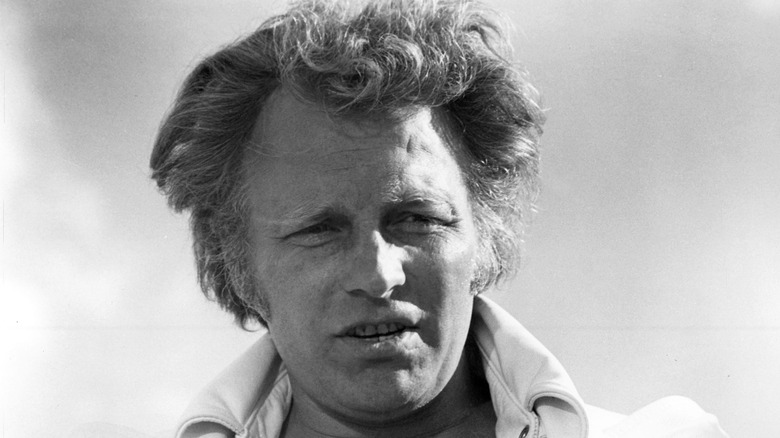

Evel Knievel was a man who lived a life so ridiculously over the top and filled with insanity, running his biography through a plagiarism checker brings up the dictionary definition of the word "badass." He spent decades risking his life, breaking bones and generally flipping off the grim reaper by doing insane stuff like fly-leaping over burning cars on a motorcycle. With a life so storied and rich, there's a lot about the "Last Gladiator" even fans aren't aware of. Here some facts about the daredevil's wild life.

He once beat someone up with a baseball bat, when he had two broken arms

In 1977 a man called Shelly Saltman released a book titled "Evel Knievel on Tour," a biography that painted a somewhat-unflattering portrait of the daredevil. According to The Washington Post, amongst other things, the book claimed that Knievel used anti-Semitic slurs, cheated on his wife, and abused both prescription drugs and alcohol. Knievel was incensed upon learning of the book's contents and set out to prove to Saltman he wasn't a violent, unhinged crazy person by ... tracking him down and beating him half to death with a baseball bat in a parking lot. That seems counterproductive, but whatever works for you.

But here's the truly insane thing — at the time of the attack, Knievel had two broken arms. In a 1998 interview with Vibe Magazine, Knievel admitted that, when the attack took place, he had both his arms in casts thanks to a recent crash that had nearly killed him. Not wanting two broken arms get in the way of whupping Saltman's behind, Knievel had one of his cronies hold him in place as he awkwardly swung the bat at his head. Saltman survived the attack with a fractured arm.

Saltman sued Knievel and was awarded several million dollars in compensation, money Knievel refused to pay ... while simultaneously having a limousine take him to and from his community service sentence and bragging about how he'd do it again. Saltman would later claim he bore no ill will to Knievel, since the incident basically ruined the daredevil's career and cost him his lucrative endorsements. That said, he was apparently still annoyed enough that he attempted to sue Knievel's widow when he passed away in 2007 (via the BBC).

Evel Knievel sold insurance to patients in a psychiatric hospital

Given the amount of time he spent in hospitals or staring at a crashed motorbike with his hands on his hips and his brow furrowed, Evel Knievel was likely well aware of the ins and outs of the insurance world, or at least hopefully, considering he used to sell it for a living.

The story goes that, according to "Evel Knievel: An American Hero," by Ace Collins, to support his young family while recovering from an accident (a recurring trend in Knievel's life), he decided to try his hand at selling insurance for the Combined Insurance Company of America. Handsome, confident and gifted with an almost-magnetic personality, Knievel quickly established himself as the company's top salesmen for the Montana region, often selling more policies in a day than most people sold in a month. But it wasn't enough.

Wanting to establish himself as the company's best salesmen, period, Knievel walked into a hospital in Warm Springs and sold 271 insurances policies in a single day. Knievel's superiors were super-impressed, lavishing praise on him and holding him up as an example of what every salesman should aspire to be. It didn't even matter that 120 of those new clients were patients suffering with various mental problems (via the Express) — it's all about that cheddar, baby, and Knievel had brought in tons of it.

While they were apparently okay with exploiting the mentally vulnerable, higher-ups at the company weren't happy when Knievel insisted that he be immediately promoted to vice president of the entire company for being so good at selling insurance. Not wanting to stick their best salesmen in an office, executives tried to persuade Knievel to stay in his current position, which clearly didn't work since he's remembered for being a stuntman and badass daredevil, not a suit who sold insurance. Knievel quit Combined Insurance shortly afterwards.

He once did a wheelie, in a dump truck

Perhaps no story better sums Evel Knievel's flair for theatrics more than the time he spent working at a copper mine in Butte, shortly after leaving high school in his sophomore year. One of Knievel's many duties at the mine was to drive a huge dump truck, a vehicle he took one look at and decided that it would look way cooler doing a sick wheelie.

So how does one perform a wheelie in a dump truck, you ask? Well, if you're Evel Bloody Knievel, you ask someone to drop a six-ton boulder, as per "Evel Incarnate," by Steve Mandich, in the back of that badboy, and then you curbstomp the gas pedal like it owes you money. Knievel succeeded in pulling off that wheelie but accidentally crashed into a bunch of power lines. This resulted in his being fired, because even the most charismatic of folks can't survive the wrath of bosses panicking over their bottom line.

He tried to give the president a big pair of elk antlers

As a young man, Evel Knievel enjoyed a successful career as a tracker for inexperienced hunters, guaranteeing them big game or their money back. Now, while Knievel was a skilled hunter, his confidence about his ability to track and find big game was due more to how he was sneaking hunters into Yellowstone Park to illegally poach the delicious, unsuspecting elk living there.

At the time, hunting wasn't allowed at Yellowstone, but the game wardens would frequently cull elk to maintain herd sizes, as per "Evel Knievel: An American Hero," by Ace Collins. Knievel reasoned they wouldn't mind him helping out by killing a few himself. Well, they did mind and asked him to please stop poaching animals. He took exception to this request, pointing out that it might be a good idea to sell off the right to hunt the elk they were going to kill anyway, both to raise money and to stop the meat going to waste. When the Park Service refused to listen, he marched, hiked, and hitchhiked all the way to Washington, carrying a massive set of antlers while collecting signatures for a "let us kill the damn elk" petition.

He then walked straight into the White House and asked to meet with JFK. Upon learning that the president was busy, he left the antlers with his secretary, and went to Capitol Hill to yell at some congressmen. Largely as a result of Knievel's efforts, the culling of elk in Yellowstone was soon stopped — now, every year a number of them are relocated to areas where hunting is legal, to maintain the population. Evil never wins, but Evel does.

Evel Knievel used to jump over snakes and mountain lions

While Evel Knievel is best known for jumping over ever-increasing lines of buses and cars, at the very beginning of his career the daredevil made ends meet jumping over wild animals, like mountain lions and snakes, instead, notes The Washington Post. For the most part, this was no more dangerous than jumping over a car, since it's not like an animal would attack a screaming hunk of metal flying over its cage or anything, but Knievel knew it would draw a big crowd.

That said, this one time, while trying to jump over a 40-foot-wide box with hundreds of angry snakes, Knievel crashed and accidentally released them all. When the snakes began making a beeline for the crowd, Knievel heroically ... told the snake handler to deal with it by himself and walked off, as per "The High-Flying Life of Evel Knievel," by Leigh Montville. As expected, the stunt shocked and amazed the crowd who dutifully went home and told everyone about it, laying the groundwork for his daredevil career. And if it didn't, and he had to become a store manager somewhere, he probably could've done that too. Dude clearly knows how to delegate.

He never worked out exactly how far he could jump before a stunt

Yes, even though his job was to jump over large gaps on a motorcycle, Evel Knievel claimed that the only thing he ever used to gauge whether a jump was possible was his own "guesstimate" about whether it looked doable (via the Independent). Knievel once went as far as admitting that he used no science or math beforehand to calculate trajectory or maximum distance or anything like that, trusting instead his own judgment and ability to not die if things went wrong.

In other words, every time Knievel lined up to do a stunt, he had zero idea if it was even possible ... and did it anyway. The reason why Knievel took this risk is because he was often quoted as saying that a man should never go back on his word, as per "The Seventies," by Bruce J. Schulman, which for him meant that, if he told crowds he'd jump over 40 buses, he'd bloody well try and jump them all, even if he had no idea such a feat was possible.

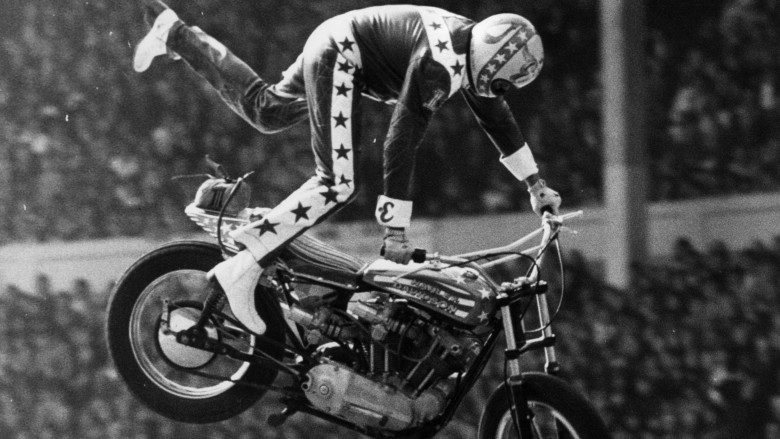

He was a walking advertisement for motorcycle helmets (literally)

At the apex of his career, Evel Knievel was known just as much for his spectacular crashes as he was for his successful jumps. Ever aware that his actions would no doubt inspire copycats, Knievel made a promise to himself to never be seen riding his motorcycle without a helmet. Knievel was a staunch proponent of mandatory helmet laws and would preface most interviews by explaining that anyone who rode a motorcycle without a helmet was, in his eyes, "a go*****ed fool" (via Big Bikes). Knievel went as far as insisting that any promotional stills of him on his bike, where the bike was implied to be in motion, should show him wearing a helmet.

He also spoke at a 1987 hearing about a mandatory helmet bill, imploring the crowd of gathered legislators to not underestimate the value of a helmet, offering himself as an example. As he took the podium, Knievel was fittingly introduced to the crowd as "the best walking commercial for a helmet there is," before an assemblyman noted that he'd broken every bone in his body except his head. Because he was no bonehead (via the Smithsonian).

Nobody really knows how many bones he broke

The Guinness Book of Records claims that Evel Knievel broke or fractured some 400-plus bones during his long and storied career, a figure that has been touted all across the web as fact, despite Knievel himself dismissing it as an exaggeration. And when Mr. Promote-Myself-At-All-Costs calls BS on something promoting him as basically a superman, maybe we best listen.

Exactly how many bones Knievel broke during his years as a stuntman will likely never be properly established, as there's no comprehensive list of the injuries he sustained. However, Knievel himself once claimed that, by his own estimation, he probably broke about 35 bones and spent half the time between 1966 and 1973 recuperating in a hospitals, or needing a wheelchair or crutches (via Magic Valley). Even still, this figure isn't entirely trustworthy, as Knievel allegedly fell over several times after his retirement, playing golf or while relaxing at home. This means we actually have no idea how many bones the man famous for breaking the most bones actually broke during his lifetime. All we know is it's many, many more than we ever hope to break.

He once gave up a liver to save a random guy's life

In addition to gravity trying to off him for decades, Evel Knievel was nearly killed in the late-90's by Hepatitis C, which ravaged his liver to the point where he needed a transplant. It was never discovered exactly when Knievel contracted the disease, though it was assumed by doctors he got it during a blood transfusion after one of his many crashes, and it had lay dormant in his system for several years.

As "Evel Knievel: An American Hero," by Ace Collins, details, true to his reputation as an iron-willed, indomitable sentinel of sucking it the hell up, Knievel refused to stay in the hospital and maintained a surprisingly positive attitude for a man who'd basically been handed a death sentence. Because he chose to stay at home, Knievel was given a special beeper, which would go off if a donor liver was found — on February 2, 1999, it beeper went off. Knievel dutifully rushed to the hospital and underwent the tests to confirm the liver was a match. It was, but during the tests, Knievel learned of a young man who was further down the donor list and who shared his blood type. This kid had taken a turn for the worse, so Knievel told his doctors that he actually felt fine and went home, giving the liver to a man he'd never met.

Luckily, just a week later, another liver that matched Knievel's blood type came around. This allowed the man who'd cheated death more than almost anyone else in history to do it yet again, while saving a young, full-of-promise life in the process.

The FBI watched and kept tabs on him for years

As you may have guessed, Evel Knievel wasn't exactly that nice of a guy throughout most of his career (though he did turn over a leaf after retirement and found God). His prickly personality saw him keeping some rather unfortunate company in the '70s and '80s — some of Knievel's more unsavory associates were tenuously linked with the Mafia, which prompted a massive FBI investigation into Knievel's dealings.

Though this investigation never resulted in any formal charges being leveled against Knievel (mostly due to a lack of any hard evidence), the file compiled by the FBI reveals that he was linked to several vicious beatings of rival daredevils, beatings it's claimed he had a hand in masterminding, as highlighted by the Express. This is something you'd think the FBI would have had an easier time proving, considering Knievel would openly admit to doing stuff like beating a guy half to death with a baseball bat. Though really, impossible jumps, faulty rockets, and Grand Canyons couldn't stop Knievel, so why should we think a bunch of flesh-and-blood government agents stood even a tenth of a chance?

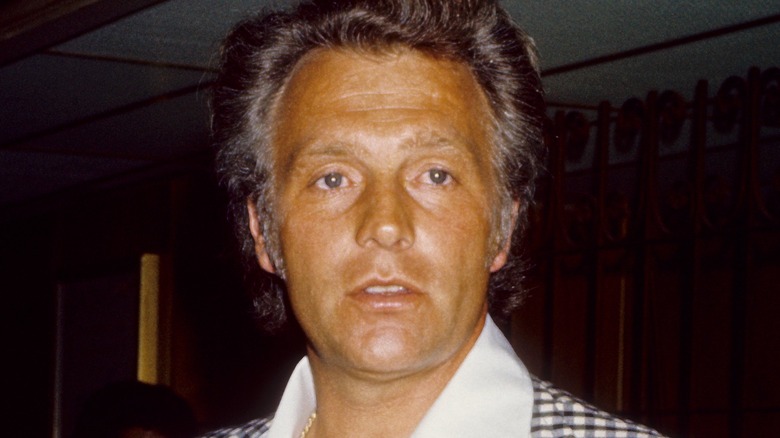

The dawn of Evel

Evel Knievel certainly knew how to market himself in a way that would make him memorable to audiences, and part of that was performing stunts with a flashy, mildly salacious, and amusingly rhyming stage name. The man born Robert Knievel came up with the Evel moniker long before he started defying physics with his jumps and stunts, but his motorcycle was involved nevertheless. According to his origin story on his official website, Knievel got spotted by Montana police one night in 1956 when he was driving his bike far above the speed limit. A high-speed chase ensued, only ending when Knievel crashed his motorcycle. Charged with reckless driving and tossed into a cell at a small jail, the night guard came around for roll call and noted the presence of a local criminal named William "Awful" Knofel.

The nickname rhymed with the last name, and Knievel that sounded so cool that he wanted a rhyming name fit for a troublemaker, too. "Evil" rhymed with Knievel, so he quickly settled on that. However, he changed the spelling, which matches that of the last four letters of his last name, because he didn't want people to think he was actually evil, just playfully dangerous.

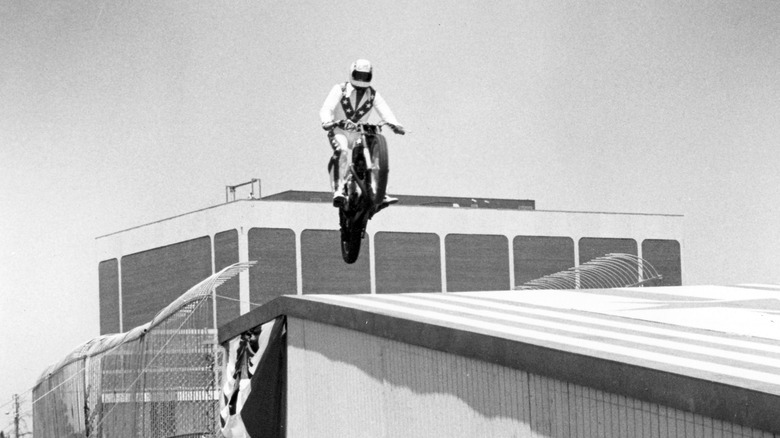

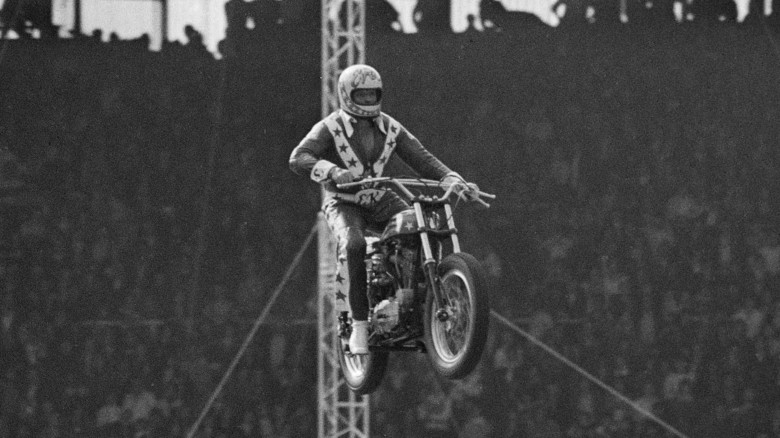

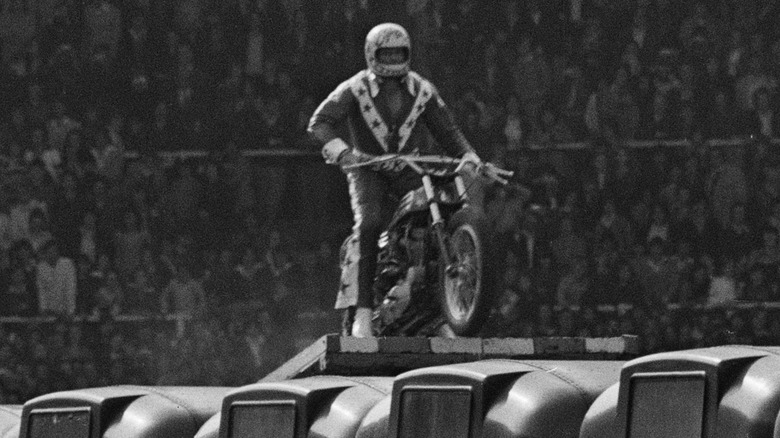

He was the Liberace of stunt biking

Evel Knievel is forever linked with the costume he wore during his most famous and memorable motorcycle stunts: a leather suit (with matching helmet) inspired by the red, white, and blue, stars-and-stripes pattern of the American flag. While Knievel's popularity coincided with the patriotic boom that led up to the celebration of the American Bicentennial in 1976, he didn't necessarily dress himself in custom-made flag chic to make any political statement

"I wasn't trying to appeal to anybody's patriotism by wearing the red, white, and blue," Knievel told ABC Sports Online (via Community Plus). "I really detested the publicity motorcycling was getting at the time I started in the '60s. I didn't like the Hell's Angels at all." To differentiate himself from biker gangs, and motorcycle enthusiasts who enjoyed a bad, even criminal reputation at the time, he wore a flag-patterned outfit instead of the black leathers commonly associated with the pastime. The actual style of the suit — all loud patterns, flares, and jumpsuit-like — was inspired by two very theatrical musicians: '70s-era Elvis Presley and Liberace, according to "Legendary Motorcycles."

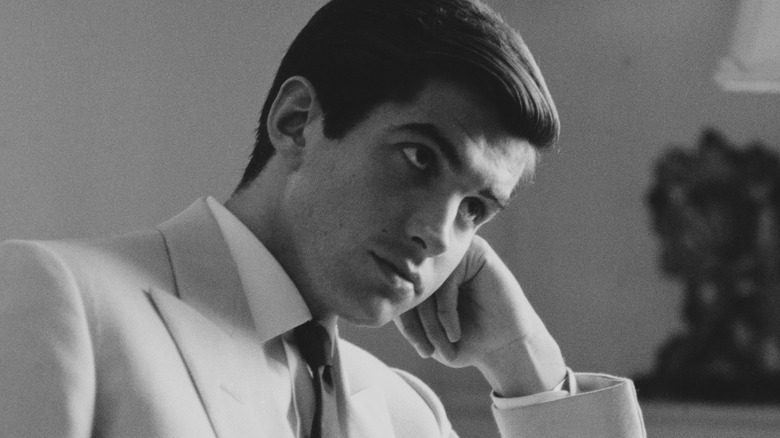

Viva 'Viva Knievel!'

Evel Knievel was such an important cultural force in the 1970s that two movies were made in his honor. The first, the glowing biopic "Evel Knievel," hit theaters in 1971 and starred George Hamilton as the daredevil, working from one of the first produced scripts by John Milius, writer of "Dirty Harry," "Red Dawn," and "Apocalypse Now." The second, "Viva Knievel!", came around in 1977. It's a full-on action movie about a world-famous death-defying stunt biker named Evel Knievel, played by the real Evel Knievel.

The film is "so absurd it simply has to be seen to be believed," according to Tony Sloman of Radio Times. Also starring luminaries like Gene Kelly and Lauren Hutton, per Variety, Leslie Nielsen of "The Naked Gun" plays a wicked drug trafficker who plans to lure Knievel to Mexico, where he'll murder him, steal his truck, and replace it with a similar looking one that's been loaded with cocaine. The fictional Knievel avoids death and defeats the bad guys, of course, portraying himself as "a saintly combination of Batman and Billy Graham," according to Andrew Nickolds of Time Out. Not only did critics find "Viva Knievel!" (Knievel's one and only star vehicle) lacking, so did audiences. It was a box office bomb, with a low $2.4 million haul, per Film Talk.

How Evel Knievel once swindled a hockey team

Before his bike jumping career began in earnest, Evel Knievel dabbled in another sport. As a 19-year-old living in Butte, Montana, in the late 1950s, according to Hagerty, Knievel formed a semi-professional hockey team called the Butte Bombers. The team played mostly small and modest matches, but in 1960, Knievel, also a player, persuaded the Czechoslovakian team to trek to Butte for an exhibition game against the Bombers, convincing the elite squad that it would be a good pre-Olympics training exercise, according to the Niagara Falls Review.

The game was hopelessly one-sided, with the Czech team unsurprisingly blowing out the bombers with a final score of 22 to 3. During the game, Knievel solicited cash donations for spectators to help pay off the opponents' substantial travel expenses. But then Knievel got himself thrown out of the game. By the time the match ended, Knievel had fled from the arena, and the cash had disappeared, too.

How much did he earn for his stunts?

How much money can you really earn for launching a motorcycle over chasms and objects? Stunt men and women can make a good living when they're doubling for movie stars, but winning your daily bread through dangerous feats under your own name is another matter. Evel Knievel was able to maintain a career doing exactly that for decades, so there was definitely money to be made.

According to K and K Promotions, Inc, which handles licensing for Knievel's name, the daredevil earned around $25,000 for each show he put on by 1968. But that number fluctuated throughout his career, and sometimes amounted to significantly less than what was advertised. When Knievel attempted to jump Snake River Canyon, he declared to the press that the stunt could bring in $20 million. By the time he'd done the jump — which was a failure — he'd downgraded that estimate to $9 million. And he later told The New York Times that his take would probably come to something more like $3 million.

Matthew McConaughey did the eulogy at his funeral

Asked in 2020 if there was any famous person or role he would like to play, Matthew McConaughey told SiriusXM (via YouTube) that he'd considered portraying Evel Knievel for some time. "I don't know if I'll ever do that one, but that's something I've been circling for, s***, 20 years," he said. A script never came together that met with McConaughey's approval, but he found Knievel's passion for life — most intensely experienced in the moments before his jumps — captivating. And besides, Knievel was a personal friend.

That made McConaughey a fitting person to deliver the eulogy at Knievel's memorial in December 2007. The service, held in the stuntman's Butte, Montana hometown and visited by thousands according to People, included other celebrities and a playlist featuring Frank Sinatra's "My Way." McConaughey spoke for nearly seven minutes on his friend (via YouTube). "He's forever in flight now," he said, and added words from his own father's funeral: "Just keep living."

He once kidnapped his girlfriend

In its eulogy for Evel Knievel, the Los Angeles Times described his marriage to Linda Joan Bork as a union of childhood sweethearts. And in a sense, that was true; the two did know each other from their high school days, dated as teenagers, and were married for almost 40 years. But some would strain to find sentimentality or romance in the period before their married life.

According to Stuart Barker's "Life of Evel: Evel Knievel," Bork's family thoroughly disapproved of Knievel, who was three years her senior, a high school dropout, and often unemployed. They forbade her from seeing him, so in response — Knieval often claimed — he tracked Bork to an ice rink and kidnapped her. The two made for Idaho, where Knievel planned to press her into an elopement. For all the tall tales the stuntman spun about his life and career, this one had some corroboration: Bork's grandmother remembered the kidnapping, and Bork herself confirmed it on camera for the documentary "Being Evel" (via an IndieWire review).

No charges resulted from the kidnapping; Bork didn't want to press them, and the incident was considered by law enforcement a case of delinquency on her part, aided and abetted by Knievel. Bork's father obtained a restraining order that kept the young pair apart for two years, but in 1959, they tried to elope again, and this time, they succeeded.

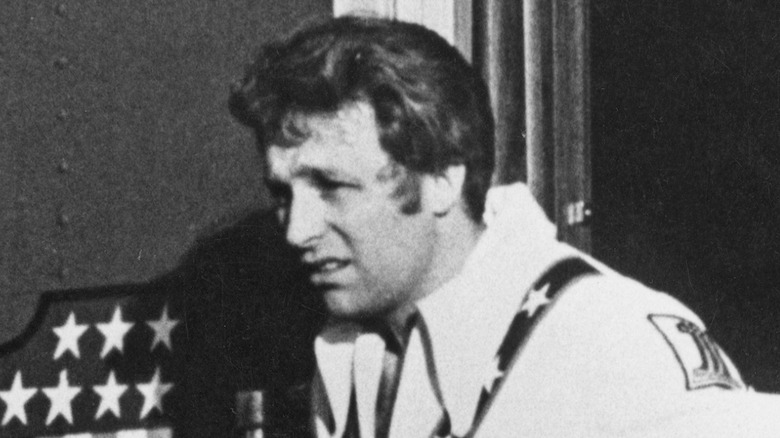

He forced George Hamilton to read a script at gunpoint

Even with the spin taken away, Evel Knievel's life and career would strike many as wild enough to be the stuff of movies. Actor George Hamilton's image in 1970 was more polished and self-aware than what Knievel tried to project himself, but when Hamilton took a shine to the stuntman's story and inquired about producing and starring in a biopic, Knievel went along (per Stuart Barker's "Life of Evel: Evel Knievel.")

To say the two men had an uneasy working relationship is putting it mildly. Hamilton told Pop Entertainment that Knievel was mercurial, jealous, and dangerous. "He wanted to portray himself," said Hamilton, "and he did go and make his own movie later on." Hamilton said that screenwriter John Milius convinced him to read the script for Knievel. It was a script reading like no other, Hamilton told the makers of "Being Evel" (via an IndieWire review), because the man whose life story they had adapted held a gun to Hamilton's head through the whole thing.

The film, a sanitized version of Knievel's life, was a modest success according to "Life of Evel." But Knievel himself grew upset about his meager pay for his own life story, and, perhaps foreshadowed by the aforementioned script reading at gunpoint, was highly jealous of Hamilton's comparatively larger cut.

He became a Christian later in life

Given his nickname, his lifestyle, and his public image, Evel Knievel was probably not high on anyone's list of celebrities likely to become a born-again Christian. But in April 2007, just a few months before his death, Knievel converted to Christianity, undergoing baptism for all the viewers of Robert Schuller's "Hour of Power" to see, as reported by AP (via KABC-TV Los Angeles). For good measure, he spoke before the congregation on his conversion for almost a half-hour.

The church Knievel joined, Crystal Cathedral, was facing financial trouble and fallout from its orchestra conductor's suicide when the stuntman underwent his conversion, according to Christianity Today. Knievel's baptism generated some publicity for the church; the day he addressed the congregation, Schuller found hundreds prepared to be baptized themselves. Knievel's ill health at the time led some cynics to speculate he was only converting due to a fear of death. "Let them say what they want to say," was Knievel's reply. "I'm a long ways from dying." While his conversion may have been sincere, Knievel's estimate of his time left on Earth was not; per The New York Times, he passed away that November.