The Mythology Of Medusa Explained

Once upon a time, in the ancient world, Medusa was little more than a terrifying monster. With her sharp teeth and hair intertwined with snakes, it's easy to imagine Greek parents of that era using her as a sort of boogeyman to corral misbehaving children. We have no real evidence that such a threat was ever actually thrown out there in archaic Greek or other ancient languages, but there's no doubt that Medusa was a frightful creature for people of all ages.

Even today, most of us assume that we've got a pretty good handle on Medusa's story. Or at least we've got a broad understanding of the tale, which involves a snake-haired woman whose mere glance can turn even the bravest adventurer into a stone statue. Eventually, one of those classic Greek heroes comes along and beheads her, ending the menace of this monstrous Gorgon forever. Well, except for all of the Medusa heads that proliferated in ancient and modern art, including the grotesque version taken as an emblem by the warrior goddess, Athena.

But it turns out that the mythology of Medusa is actually pretty complicated, with varying backstories, different characters, and an increasingly complicated set of interpretations over the centuries. Was Medusa always a monster? Did she choose to live alone? Did she have any companions? How have we changed her story in the modern era? And haven't you wondered how she got snakes for hair, anyway? This is the mythology of Medusa explained.

Medusa's origin story involves assault

In many tellings of the Medusa myth, she does not begin as a grotesque, snake-headed monster, though it's true that some of the earliest versions of her story simply assume that she was born that way. But, as time went on, Vice reports that her story grew in complexity and tragedy. Rather than being a native-born monster or at least a human sister to the monstrous Gorgons, Medusa instead began her life as a perfectly ordinary, if beautiful human woman.

But being beautiful in the ancient world was just as much a liability as it can be today. In Medusa's case, the incredibly powerful god of the sea, Poseidon, came to call. As Roman poet Ovid relates in his Metamorphoses, Poseidon, presumably being used to taking whatever he wanted, took Medusa, too. Even worse, he did so in a temple dedicated to Athena.

Athena was upset at the desecration that had just gone on in her temple. Only, she turned her wrath on Medusa. The poor woman was afflicted not only with snake hair, but also a hideous visage and the unfortunate power of turning people to stone with a single gaze. And Poseidon, it seems, was free to go off on his own way mindless of the suffering he'd caused.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Medusa was part of a sisterly trio of monsters

Oftentimes, Medusa is depicted as living alone, usually surrounded by the petrified remains of people she'd either accidentally or intentionally turned to stone. But, according to quite a few versions of her tale, Medusa is actually one of three terrifying and powerful sisters: the Gorgons.

According to Britannica, a Gorgon was apparently once thought of a single monster or general underworld figure. However, as time went on, this frightening specter became three. According to ancient poet Hesiod, they were Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa. In some artworks, all three had hideous faces and snake-infested hair.

Though she was typically shown as a very powerful figure, Medusa had a key disadvantage: she was mortal. Her sisters, meanwhile, were immortal. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, this didn't mean that they mourn Medusa's death at the hands of human hero Perseus. After he beheaded Medusa, Stheno and Euryale chased after Perseus, wailing in grief and anger as they attempted to apprehend the killer. Athena, in another move that really doesn't put her in the best light for modern readers, listened in on the proceedings. Rather than stepping in as she did earlier or in any number of other myths, Athena instead invented the flute to mimic the immortal Gorgons' sounds. She at least got some small comeuppance when she realized that, to play the flute, she had to also mimic the faces of the Gorgons as well.

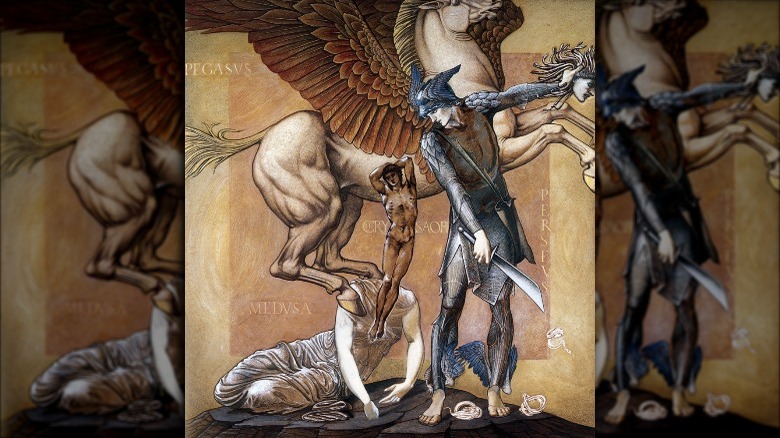

Perseus cut off her head to become a hero

Much of ancient Greek mythology tends to focus on the exploits of adventurous young men who are set on becoming world-renowned heroes. But, as so many myths dictate, a man needs to first prove himself before he can be considered a hero. And that often means that he has to accomplish a seemingly impossible task or defeat a fearsome, deadly foe.

For the budding champion known as Perseus, that foe was to be none other than Medusa. According to the World History Encyclopedia, it all started when King Polydectes fell in love with Perseus' mother, Danae. Previously Zeus had taken a liking to young Danae and impregnated her, leading the young woman's father to set her and the resulting semi-divine baby adrift on the sea. The pair survived and settled in Polydectes' territory. Perseus and Polydectes clearly didn't like each other, with Perseus blocking the king's amorous advances. Polydectes settled upon a scheme whereupon he would ask the younger man for Medusa's head. Clearly, it would be a deadly quest and the annoying kid would be out of his royal hair forever.

Yet Perseus got an assist from the gods. He managed to slay Medusa at her cave, using a reflective shield courtesy of Athena that allowed him to spot the Gorgon without directly meeting her gaze and turning to stone. The helmet of darkness, given to him by underworld deity Hades, also helped him avoid the other angry Gorgons.

Her blood produced a magical horse

As you may have already guessed, beheading someone, whether they are a regular human or a divine being, is bound to produce a fair amount of gore. And, in the case of Medusa's decapitation, it also gave rise to not one, but two new creatures that sprang forth from her blood.

The most well-known of the pair is surely Pegasus, the winged horse that often competes for the attention of fantasy-minded youngsters alongside the unicorn. According to the World History Encyclopedia, the horse was actually the product of Medusa's encounter with Poseidon, the sea god also being the deity of horses in ancient Greece (via Britannica). Pegasus sprang forth fully formed from Medusa's spilled blood and was given away to Bellerophon, the son of Poseidon.

But Pegasus wasn't the only one to emerge from Medusa's body. According to Theoi, the winged horse was accompanied by Khrysaor, a magical creature who takes different forms depending on the story you're reading. In some, he's simply a gigantic man who lumbers out of the Gorgon's blood. But other legends claim that he was actually a boar sporting a set of wings, though no one seemed quite as enamored of him as they were of the more television-ready Pegasus. Hesiod and Roman poet Diodorus Siculus both claimed that Khrysaor was named for an aor, a kind of golden sword that he carried.

Athena took Medusa's head as an emblem

For many people, Athena, goddess of war, reasoning, and patron of Athens (via Britannica) doesn't come off terribly well in the story of Medusa. Sure, if you believe that Medusa was a consenting partner to her encounter with Poseidon, Athena may have a right to be offended that it all took place in her own temple. But, if Medusa was assaulted, then the goddess seems to be only punishing the victim. Athena's later actions don't exactly speak to her holding any true sympathy for the Gorgon or her kind, either.

Take the aegis. As Britannica notes, this term generally applies to a sort of cloak or chest piece made out of leather. Because it's associated with the gods and especially head god Zeus, an aegis is a pretty big deal and considered to be incredibly powerful. It's no wonder, then, that Athena wears one of her own. The goddess's special twist on the aegis look was to place the decapitated head of Medusa right there in the middle of her aegis. It's said that Perseus, done with his adventure and presumably not wanting to hold on to a monstrous woman's loose head, gave it to Athena as a gift. The goddess apparently was really into it, and the frightful head of Medusa was used as an intimidating emblem on Athena's gear and statues of the goddess for centuries to come.

Medusa's image has been used to ward off evil

Though, going by the myths and legends, Athena was the first one to claim that image of Medusa's severed head as a personal symbol, it wasn't to remain solely hers for long. Eventually, as the Metropolitan Museum of Art notes, it became a more widely used apotropaic symbol meant to scare off evil. The general thinking was that the frightening look of a bodiless Medusa would be intimidating enough to scare off other bad forces.

Even later, the sight of her head became little more than a decorative flourish known as a gorgoneion. In this form, Medusa's head pops up in temples, where she's still a grotesque figure with a lolling tongue, dangerous looking teeth, and popping eyes. Sometimes, Medusa even sports a beard, just to underline the image of her as something more animal than human. She also appears in less serious contexts, like at the bottom of drinking vessels as a cheeky surprise to the imbiber after their last gulp.

Some historians think she represented a dead body

Simply considering the practicalities of just how a bunch of snakes would survive attached to a person's head, much less how that individual would be able to turn people to stone merely by looking at them, is enough to make the whole Medusa story crumble. Only, it could be that there's just a touch of truth to Medusa's story, after all. Yet, diving into the details of how the ancients may have come to create Medusa might require a strong stomach.

That's because the distended face of the Gorgon may well have been inspired by a days-old corpse, according to some researchers. Per ThoughtCo, the most misshapen representations of Medusa, with a distended tongue, bulging eyes, and bared teeth, could recall human remains that have begun to decompose.

As "Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon" argues, people living in the ancient world would have been far more likely to encounter a dead body than many of us are today. And, given that they lived in a time where embalming and preservation techniques were rudimentary at best, those remains were also more likely to be pretty far along in the decomposition process. Battles would have been an especially gruesome yet rich source of lifeless bodies, many of which could be left without burial or cremation for quite some time. Perhaps such a traumatic sight embedded itself into a collective cultural consciousness that eventually produced the grimacing Medusa herself.

Medusa's story underlies a complicated take on beauty and power

Older representations of Medusa are pretty uncompromising in their takes on the Gorgon. She is, simply put, hideous. Some of the earliest representations of her are intentionally off putting, with a tusked, bearded, pop-eyed Medusa glaring out at viewers (via Metropolitan Museum of Art). But even the ancients couldn't resist delving into the other side of Medusa's story, where she is a beautiful woman who, by choice or accident, is forced into a situation that isolates her from the rest of society. A jar from around 450 BCE may well be the first depiction of Medusa as beautiful, though she's still in the process of losing her head courtesy of Perseus. Interestingly enough, her hair is entirely snake-free and she sports a pair of large, feathery wings.

But delve even deeper, and you'll see that Medusa's story isn't all about looks. It's also undeniably about power, says Artsy. As she became more and more attractive, Medusa's allure became a symbol of her power in the world, a might that was often distinctly feminine. It was this sort of power — dangerous, beautiful, and connected to women — that both ancients and more modern people felt needed curtailing, oftentimes at the end of a sword. Often, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "monstrous" women like Medea or the murderous Clytemnestra were directly compared to the bestial Medusa in an attempt to curtail and understand their power.

Medusa's head was made more beautiful for later eras

Centuries into the life of the Medusa myth, it was pretty well-established that her disembodied head was going to be a regular feature of everything from cups, to temples, to vases, to vengeful goddess' armor. Her visage leered out from many places, daring fellow evil spirits to mess with the people beyond entryways or behind bits of armor. It may have all seemed very set in stone — no offense to those who were actually turned into stone by Medusa herself.

But, as time wore on and tastes changed, Medusa's look had to change, too. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the shift from Archaic Greece through to its Hellenistic period meant that Medusa became steadily more attractive, though she was still consistently set apart and depicted as a monstrous woman. This is the beginning of the beautiful woman with snake hair that is so familiar to people today.

Medusa continued to be a common motif in later art periods, including the European Renaissance. Big name artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Caravaggio painted Medusa, with Caravaggio's fully snake-haired Medusa acting as the inspiration for modern depictions of the Gorgon (via Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Medusa shows up in the world of politics

After a few centuries of circulating as both a mythological creature and a decorative motif, it was natural enough that Medusa would eventually become a political figure as well. And, as a figure that is often depicted as a beautiful, powerful, and deadly woman, she has often been used to criticize female politicians.

Consider, if you can, the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Over the course of that contest, it became clear that the election came down to two candidates: Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. Though Clinton, having held office in numerous capacities, including Senator and Secretary of State, was clearly the more politically experienced candidate, she had what many considered to be a significant handicap: she was a powerful woman.

There were quite a few ways, both covert and overt, that Clinton came under fire for this state of being but, as The Atlantic reports, Medusa got roped in eventually. Some political images drew on classical art to show Trump as Perseus, hefting aloft the decapitated, screaming head of a snake-haired Clinton. At least Clinton was joining a pretty packed club of people who have been unfavorably and rather violently compared to the Gorgon. These include German Chancellor Angela Merkel, talk show host Oprah Winfrey, fellow former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, and just about any other powerful woman who has had an independent opinion in public.

Medusa has become a powerful feminist symbol

There's no denying that Medusa's story, in its many forms, is largely a tragedy, and certainly so when you consider things from her perspective. She often seems to have been minding her own business when an ultra-powerful god sexually assaulted her, and in a sacred space, no less. In what must surely be one of the ultimate acts of victim blaming, yet another god disfigures Medusa and forces her to live in isolation because of her new and terrible powers. After all, few interpretations of the myth care to wonder if Medusa really wanted to turn anyone to stone. The whole story has only gotten more complicated over the years, as Medusa has become a symbol for the oftentimes attractive and powerful women who must be contained and silenced at all costs.

But there's a flip side to the story. Now, after she's spent so long as a frightful and tragic figure, some people are taking Medusa up as a feminist symbol. Per Vice, that actually kind of started around the time of the French Revolution, when she became a symbol of rebellion taken up by anti-monarchy forces. Things really picked up steam in the 20th century, when feminist theorists began to reclaim Medusa in more direct contexts, framing her as representative of all the powerful women who existed and are yet still to come. And, for many, it's now possible that Medusa can be reclaimed and welcomed back after all this time.