Most Dangerous Animals In Australia

It's a pretty common claim on the Internet that Australia's filled to the brim with dangerous animals, and it's not entirely without basis: As an article in The Conversation points out, the so-called "Land Down Under" has quite a few animal species with incredibly lethal venom, including some of the world's most venomous snakes. Experts from the Queensland Museum say that all of the country's "dangerously venomous" terrestrial and marine snakes came from a single group — the hollow-fanged elapids — and originated from one particularly lethal ancestor. (Which totally makes sense from an evolutionary perspective: A snake with stronger venom would be better equipped to kill prey that others can't, increasing the chances it could survive, reproduce, and pass this trait on to its offspring.)

That's not to say, however, that everything in Australia is out to kill you. This couldn't be further from the truth: For starters, the country certainly doesn't have a monopoly on deadly animals. Additionally, most of them won't harm a hair on your head, provided you keep your distance. Interestingly, the European honey bee has a higher kill count than Australia's most dangerous (and far more venomous) spider, due to the sheer number of people they sting and the allergic reaction that some victims suffer (via Australian Geographic).

Fact is, even though you'll find plenty of killer critters in Australia, many (but not all) of them would be more than happy to leave you alone. Here are some of the most dangerous animals in Australia.

You're unlikely to survive an encounter with a saltwater crocodile

According to Oceana, crocodiles and related species have a PR problem: If you were to encounter them face to face, they'd probably be just as unhappy (and eager to get away) as you. However, that's not the case with the saltwater or estuarine crocodile, a species with a well-documented history of territorial aggression against humans. Hardly surprising, considering that it chomps down with a force of nearly 17,000 newtons, the strongest bite force ever measured of any living land animal. For perspective, that's one-fourth of the car-crushing bite force of a Tyrannosaurus rex (via Business Insider).

Active year-round, saltwater crocodiles are found across Australia, from northern coastal areas and drainages to islands about 60 miles from the mainland (via the Australian Museum). While it can survive in seawater, these reptiles prefer living in brackish (somewhat salty) water. National Geographic describes this 23-foot, 2,200-pound carnivore as a "classic opportunistic predator" that snacks on just about anything unfortunate enough to pass by their territory: birds, sharks and other large fish, water buffalo, wild boars, monkeys, and even humans. Few prey can survive a surprise attack from the world's largest reptile: It waits patiently under the water's surface until it spots its next target, after which it comes out of hiding while thrashing its enormous tail. It quickly nabs its shocked prey, drowning it before turning it into lunch. Also, wounds from crocodile attacks tend to get infected, requiring prompt antibiotic treatment.

It would take very little Sydney funnel web spider venom to kill you

For such a small creature, the male Sydney funnel web spider packs quite a punch. According to the Australian Museum, this spider's body length reaches a maximum of 2 inches. However, its venom is so potent that it only takes 0.2 mg/kg of it to kill an adult human being, earning this Australian native the title of "world's most venomous spider" (via the Guinness World Records).

Males of the species are known to seek out mates at night, due to their sunlight sensitivity. As the Australian Geographic explains, this is why people find these arachnids hiding in their homes (or worse, chilling in their footwear). You definitely don't want to find one in your slipper, though: This spider's parallel fangs are so large and tough that not even shoe leather or fingernails could stop them (via National Geographic). It can kill a full-grown human in just a quarter of an hour, since its venom is particularly potent against both invertebrates (causing paralysis) and primates (attacking the nervous system, causing headaches and nausea, and elevating blood pressure). That's why these arachnids are so dangerous to humans; as the Australian Reptile Park's Ranger Mick put it, "It's just absolute bad luck in the genetics — funnel webs didn't evolve to attack humans."

Fortunately, no deaths have been recorded since 1981, after the development of an antivenom.

A blue-ringed octopus can end you in one hit

As you and your friends are swimming near the shore, something tiny and adorable catches your eye: a bright-colored octopus, smaller than your hand. Curious and excited, you pick up the little fellow. Within seconds, bright blue rings start flashing on its body. Next thing you know, your muscles have gone numb, your vision has turned blurry, and you're having trouble breathing. You begin to lose consciousness, as your companions start screaming for help. They only have minutes to save your life, as you just got hit with a neurotoxin over a thousand times stronger than cyanide (via FlipScience).

Found in Australia, the greater blue-ringed octopus is among the most toxic marine animals in existence. According to Project Noah, this mollusk prefers living in shallow waters with rubble, sand, and reefs. It only leaves its burrow when it's time to hunt for prey or a partner. While generally not aggressive, it bites when agitated. According to the Journal of Experimental Biology, its bright-blue display (which happens when it flexes its muscles and prepares to release its tetrodotoxin-laced saliva) is a warning sign against predators and threats. Victims rarely feel the bite itself, though tetrodotoxin's effects are nasty: It blocks nerve signals, causes muscle numbness, and paralyzes respiratory muscles. Oh, and there's no antidote: Only immediate artificial respiration can save victims (via Ocean Conservancy).

The inland taipan is the world's most venomous snake

Endemic to Australia, the inland taipan perfectly demonstrates how a species can simultaneously be dangerous and not dangerous, depending on human interference. Typically cited as the most venomous snake on the planet, its bite is said to be enough to make 250,000 mice take a dirt nap (via The Conversation). Interestingly enough, there has not been a single recorded incident of anyone dying from this snake's potentially lethal bite, partly because humans rarely encounter it. In fact, its far more common relative, the coastal taipan, has killed quite a few people, according to the University of Melbourne's School of Biomedical Sciences.

Inland taipans have rectangular-shaped heads that are a few shades darker than their bodies. Their back scales are yellowish-brown, dark brown, or pale fawn in color; their coloration changes to a faded hue during summertime and darkens upon winter's arrival. Found in Queensland and South Australia, it likes to hide in cracks, crevices, and burrows (via the Australian Museum).

In an interview with Live Science, biologist David Penning explained that the inland taipan "feeds almost exclusively on mammals," which is an uncommon specialty. Its venom is a toxic cocktail that attacks the victim on all fronts, with deadly compounds that cause seizures, loss of limb control, breathing difficulties, hemorrhage, and organ damage within 60 minutes. According to the University of California San Diego, a person can die from an inland taipan's bite in just half an hour.

The reef stonefish is the world's most venomous fish

Despite its well-deserved reputation as an extremely dangerous fish, it's highly unlikely that the reef stonefish would want anything to do with its human victims. This stealthy swimmer grows up to nearly 16 inches long and typically lies in wait for prey, its coloration and texture allowing it to look like a piece of coral or rock and effectively blend in with its environment (via FlipScience). Once its next meal — usually a small crab, shrimp, or fish — swims by, it leaps into action. When it's on the hunt, it can lunge fast enough to nab its prey in just a fraction of a second, according to the Professional Association of Diving Instructors. Most of the time, though, it swims at a slow pace.

What makes the reef stonefish particularly dangerous to humans and would-be predators are the 13 toxic spines lined up on its back, which stick up when the fish is agitated or disturbed. According to the Australian Museum, the reef stonefish's neurotoxin-loaded sting is particularly painful. With the right dose of venom, a single jab can kill a person. Fortunately, experts developed an antidote in 1959 that greatly reduced the chances of dying from its sting.

Fun fact: Due to its ability to absorb oxygen through its skin, the reef stonefish can survive for up to a full day outside of its watery habitat.

Don't even try to pick a fight with a cassowary

If you've ever wondered what it would be like to encounter a vicious Velociraptor — or a version closer to the man-sized "Jurassic Park" ones than the turkey-sized, scientifically accurate ones — then look no further than the southern cassowary. According to the official website of the Queensland Government, it is the "heaviest flightless bird" in Australia, and the only one among the three known cassowary species found in the country. It also happens to be the Guinness World Record-holder for the title of "most dangerous bird," and rightly so: It can kill you with a single, well-aimed kick.

Standing over 6 feet tall, the southern cassowary sports bristly black plumage, a dark blue neck, a lighter shade of blue on its head, and two red skin flaps hanging from its neck. On top of its head sits a hollow, crest-like casque, making this bird a truly striking sight. You'll want to stay out of striking range, though, as it also possesses strong, muscular legs and three-toed feet with sharp claws. Its inside claw is easily the most dangerous one, growing up to 5 inches long. In one swift, powerful motion, it can cut its target wide open, damaging the organs and causing the victim to bleed out.

Fortunately, the cassowary isn't known to be aggressive and will only attack if it feels the need to defend itself, its chicks, or its nest (via Scientific American).

The bull shark is huge, aggressive, and dangerous

Outranked only by the great white shark and the tiger shark, the bull shark has been responsible for a staggering number of recorded unprovoked shark attacks since 1580: 92 non-fatal attacks and 25 fatalities, based on the official tally on the International Shark Attack File of the Florida Museum. However, it's the unique combination of the bull shark's infamously aggressive and territorial nature, its history of mistaking boats or humans for prey, and its preference for shallow coastal waters that may make this shark a bigger threat to humans than other shark species (via Animal Diversity).

The bull shark grows up to 11 feet long and clocks in at almost 700 pounds, making it one of the largest requiem sharks known to science (via Oceana). It is capable of delivering a sickening 6,000 newtons of bite force, according to Newsweek. Unsurprisingly, this shark has no trouble chomping on a wide assortment of prey: seabirds, bony fishes, sea turtles, and even land-based and aquatic mammals.

Bull sharks reportedly have a tendency to kill whatever is in their immediate surroundings, to the point where aquariums have refused to display them, for fear that they would kill the other marine animals in their tanks. They also don't have any natural predators, except perhaps themselves; on a few occasions, injured bull sharks have been eaten by their own kind.

There is no antidote for this snail's deadly venom

Their shells may look like the type that's fun to pick up and perhaps collect, but make no mistake: Cone snails are best left alone, for your own good. The geographic cone (or geography cone) is particularly dangerous: Growing up to half a foot in length, this mollusk's envenomed jab packs enough of a punch to put a human being to sleep permanently — and worse, there's no antidote for it (via FlipScience).

According to the Australian Museum, cone snails like the geography cone can be found in tropical, subtropical, and temperate waters, typically residing on sandy ocean bottoms, coral reefs, and intertidal environments. What makes the geographic cone especially lethal is the unique, self-produced toxin that it uses to paralyze and nab its prey (via Animal Diversity). It hunts during the night, using its built-in harpoon-like weapon (a tooth attached to a proboscis) to spear, poison, and pull its prey. Interestingly, this snail can reach any part of its shell with its poisoned tooth, which is why picking up a cone shell will always be dangerous.

A bull ant can kill an adult human within 15 minutes

The Guinness World Records have crowned Australia's bulldog ant as "the most dangerous ant in the world," and rightly so: It's pretty big for an ant, and its powerful jaws are capable of injecting a serious amount of venom. As Marc Widmer, a senior technical officer at Western Australia's Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, explained in an ABC News interview, "Their venom is made up of a variant of proteins, histamines and other compounds. The mix of those, combined with a person's individual response, will typically result in a nasty reaction."

The bulldog ant (or bull ant) gained its moniker due to its aggressive attacking behavior. Once agitated, it has the ability to sting again and again and again, with each sting delivering more venom. It has even been known to stick its mandibles into its target's flesh as it stings repeatedly; reports say that adult humans have died from bulldog ant attacks in 15 minutes flat. At least three people have died from bulldog ant attacks since 1936. Bulldog ants have been known to attack small marsupials and dogs as well; worse, their bites are tough enough to penetrate clothing. And if that's not enough, the Australian Museum states that they have eyesight sharp enough to track and follow opponents 3 feet away.

The Australian paralysis tick can send you to the ICU

According to Western Australia's Department of Health, the east coast of Australia is the only natural environment in which an especially dangerous parasite thrives: the Australian paralysis tick, which does exactly what its name suggests.

In a paper published in the Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, researchers identified three different species of bandicoot as the Australian paralysis tick's most common hosts. However, these parasites have also hitched rides on (and sucked blood out of) a wide range of livestock, pets, and even human beings. Largely incapable of getting around by themselves, Australian paralysis ticks tend to climb up grass stems, branches lower than 19 inches from the ground, and other plant structures, waiting for an unsuspecting host to pass by (via the Australian Department of Health). After latching on to its new "home," the tick crawls all the way up to the host's head. It digs into the host's skin and injects saliva with anesthetic and anticoagulant properties, preventing the host from feeling their attack while simultaneously stopping the host's blood from clotting.

This tick's venom can cause some truly nasty side effects in humans, such as rashes, flu-like symptoms, partial face paralysis, allergic reactions, and even anaphylactic shock (via the Australian Museum). If not treated immediately, the victim may end up needing emergency care, antibiotics, and mechanical respiratory assistance to save them from death.

Never, ever eat a smooth toadfish

Judging from its name alone, it sounds like the smooth toadfish wouldn't make for a good meal. Historically, though, people have had a taste of this pufferfish — and the incredibly lethal poison concentrated in its skin and internal organs (via the Medical Journal of Australia).

Fishes of Australia describes the smooth toadfish as a "small pale yellowish to greenish pufferfish, with dark brown irregular spots and blotches overlain with four darker bands and a white belly." It has tiny spines embedded in its skin, giving it a uniquely smooth texture. According to the Australian Museum, this is the easiest way to differentiate it from its pricklier relative, the common toadfish.

The tetrodotoxin in the smooth toadfish's body makes it an extremely undesirable catch for fishermen, made worse by its tendency to bite on their bait (via the Australian Fish Guide). As the Centers for Disease Control states, tetrodotoxin poisoning can happen within just 10 minutes, and can cause rapid weakening, muscle paralysis, and respiratory arrest; in severe cases, the patient has less than half an hour to survive.

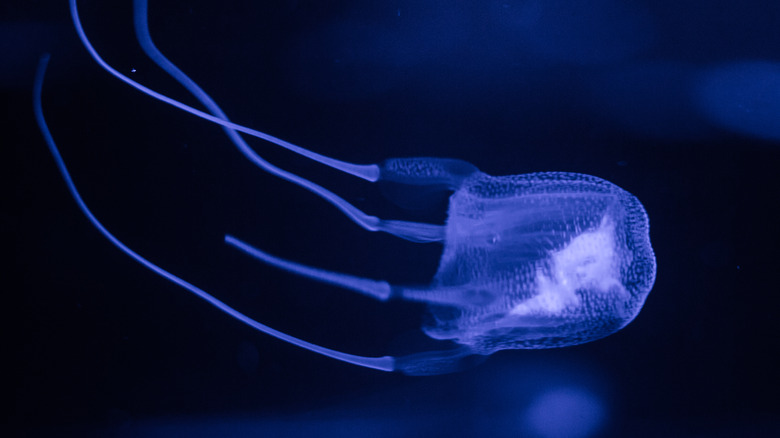

Just stay away from box jellyfish, period

Also known as the sea wasp, the box jellyfish has a well-deserved reputation for being the most dangerous jellyfish on Earth. According to the University of California Museum of Paleontology, this particular species of sea jelly has killed about a hundred people in northern Australia within the last century.

A common sight in the waters of Queensland and Western Australia, the box jellyfish can grow up to nearly 12 inches in diameter and can have up to 60 tentacles that are about over 6 feet in length (via the University of Melbourne School of Biomedical Sciences). This jellyfish delivers powerful toxins through its nematocysts, the stinging cells found in each of its tentacles. Imagine a cell with a harpoon-like structure stored inside it, and multiply that by a few million. That should give you an idea of the box jellyfish's sheer stinging power. Its effects may include a sudden burst of pain, followed by skin welting and cardiac arrest — and given the potency of box jellyfish venom, it doesn't take much time for a person, especially a small child, to die from its sting.