The True Story Of Olivia Newton-John's Nazi-Fighting Family

You may know Olivia Newton-John from her roles in films like "Grease" and "Xanadu," from her numerous chart-topping songs and four Grammy wins, or her philanthropic work. But here's what you may not know. Before she was ever born, Newton-John's family had already fled the Nazis and fought them, and shortly after her birth, her maternal grandfather would win an award that makes even four Grammys seems a big minor-league by comparison.

While the details of Newton-John's life have largely unfolded in the public eye, the story of her family — who they were, how they met, and their activities during World War II — are much less well-known. For example, did you know that Newton-John's father was not just a professor and headmaster of several schools but also an opera-singing spy who fought the Nazis? Here's the full story of Olivia Newton-John's Nazi-fighting family and the remarkable lives they led before she was even born.

Her grandfather was a physicist who fled the Nazis

Olivia Newton-John's maternal grandfather, Max Born, was an accomplished physicist and helped to establish the Institute of Theoretical Physics in Gottingen in the 1920s. Of Born's many accomplishments during his tenure, he conceived the name "quantum mechanics," notes the University of Göttingen. As detailed by Born's only son, Gustav, years later, Born was also a close personal friend of Albert Einstein, the two having met in Berlin prior to World War I.

As a Jewish family in Germany on the cusp of the rise of the Nazi regime, the happiness of Born and his wife and children — including Newton-John's mother Irene — was short-lived. In his memoirs, Born recalled the situation in Germany going from bad to worse. In one instance, he received a phone call in the middle of the night, with the caller shouting and singing a Nazi hymn. In another, he recalled the tragedy of a friend taking his own life because "he saw no hope for Germany and Europe." As Adolf Hitler came to power, an official "boycott" of Jewish citizens declared, and concentration camps soon established, Born began plotting his escape.

By May of 1933, Born had been stripped of his position at the university, and his family was forced to flee Germany ahead of Nazi pogroms. "All I had built up in Gottingen, during twelve years' hard work, was shattered," Born wrote in his memoirs. "It seemed to me like the end of the world."

Max Born won the Nobel Prize in 1954

Writing in his memoirs, Max Born recalled how painful leaving Germany was for his wife, Heidi, and family. "She was attached with all her soul to the country," he wrote, "to her home town and to the German language." And yet, when the decision was made, he wrote that she "never raised any difficulty," though the situation was "unbearable, indeed."

Born accepted an invitation to go to Cambridge, where he had previously spent two terms while studying for his doctorate. According to his son Gustav, writing for the University of Gottingen, these were instrumental in the family's decision to move to Cambridge when they were driven from their homes.

"It determined our family becoming British instead of French, Russian, American, or Turkish," Gustav Born wrote, "all through offers of jobs he received from these countries." Gustav even joined the British Army during the war, where he served as a soldier and doctor, and was stationed near Hiroshima. In fact, Gustav was one of the first doctors to treat victims of the atomic bomb, notes Queen Mary University of London, which informed his lifelong research into platelets. (He even invented the aggregometer, which essentially measures how well platelets clump together.)

Born didn't return to Germany until 1954, by which time he had already contributed considerable further work in quantum mechanics, solid state physics, and optics. That same year, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics "for his fundamental research in quantum mechanics, especially for his statistical interpretation of the wavefunction," sharing the prize with fellow German Walther Bothe.

Her father's singing brought Olivia Newton-John's parents together

Of their time in Cambridge, Gustav Born later wrote, "Since our forced emigration from Germany in 1933 the Born family owes everything to Britain — our very lives when the British people first took us in and again later when Churchill's courage and steadfastness prevented a German invasion; as well as everything else — livelihood, friendship, and love."

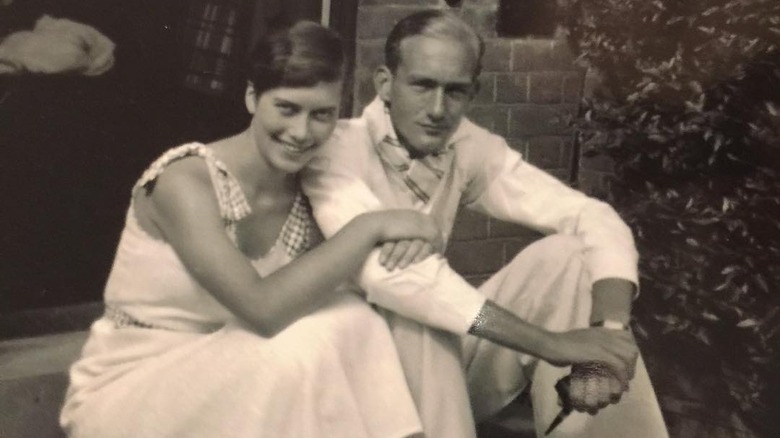

For Max Born's eldest daughter, Irene, love began at Cambridge, when she "heard a man singing in a deep baritone voice and she couldn't take another step," according to Olivia Newton-John's autobiography, "Don't Stop Believin'." "She actually followed the voice. Mum always said she fell in love with the voice before she even saw him."

The "him" was Olivia's father, Brinley "Brin" Newton-John, who was a student at Cambridge at the time. Like many members of Olivia's musically gifted family (grandfather Max Born was also an accomplished pianist), Brin was already an accomplished singer when he met his first wife. Years later, while filming a TV interview for an episode of "The One Show," Olivia was treated to a recording of her father singing an aria from "The Marriage of Figaro," which was recorded during his wartime service, (via The Express).

Olivia Newton-John's parents were married in 1937, and Brin Newton-John was commissioned into the Royal Air Force by 1940 — keeping him away from home much of the time, including for the births of Olivia's two older siblings.

Brinley Newton-John was an intelligence agent for MI5

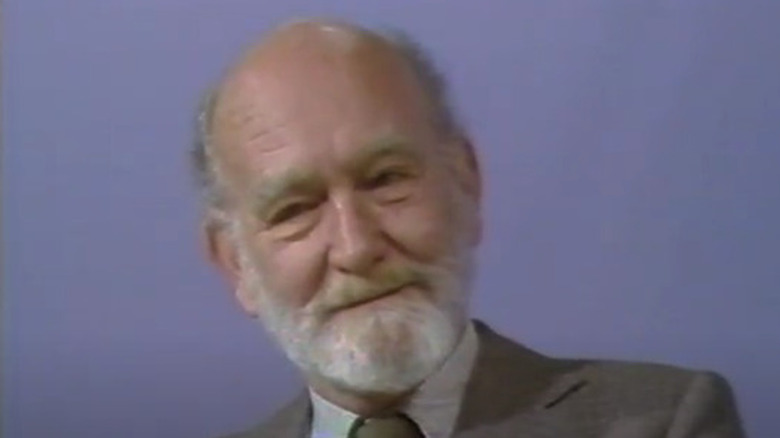

As described in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, it was in part due to his knowledge of the German language (he would later become a professor of German literature) that Brin Newton-John was drafted into the British intelligence services, also known as MI5. Due to his fluent German he was assigned to the task of interrogating captured German soldiers — most often, downed fighter pilots. His knowledge of upper-class German society helped him gain their confidence.

As he later recounted in his interview with Ron Hurst on NBN Television, his tactics weren't torture or bullying, but being friendly. "If we got them to talk," Brin recalled, "we got them to talk by being nice to them, on the whole, rather than by being bullies. I don't think I'd have made a very good bully, in any case."

"Being nice" to the captured German soldiers apparently included things like taking them out to dinner or for a night on the town. Olivia Newton-John recalled in her autobiography, "Dad would wine and dine infamous prisoners, generally the high-ranking officials in the Third Reich, in order to pry information out of them." She went on to detail an afternoon tea with Nazi leader Rudolf Hess, where Hess even gave Brin his own gun.

Brin Newton-John was involved in the capture of Rudolf Hess

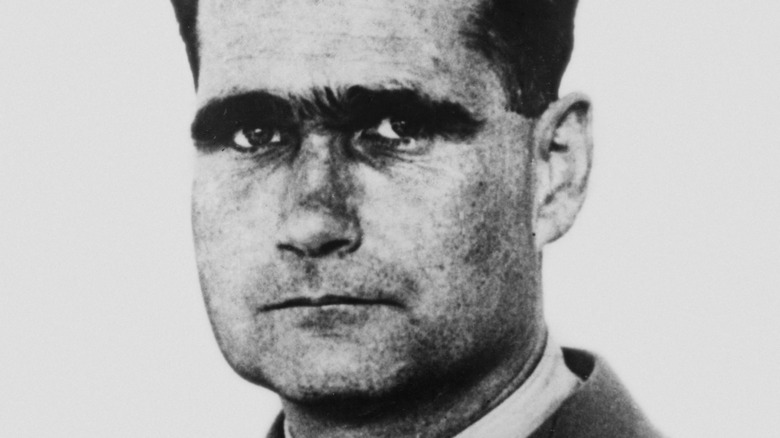

As World War II began, Rudolf Hess was at Adolf Hitler's right hand. Following the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, he voluntarily joined Hitler in prison where, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, he was responsible for copying down most of Hitler's "Mein Kampf."

By 1933, Hess was deputy party leader of the Nazi Party, but in 1941, his position of influence had begun to wane. So it was then that he cooked up a desperate plan, embarking on an unsanctioned solo flight from Germany to Scotland in an attempt to broker a peace deal with the United Kingdom. Years later, fellow Nazi Albert Speer discussed Hess' plan with him while the two served their sentences in Spandau prison.

Quoted in the Smithsonian Magazine, Speer recalled that, "Hess assured me in all seriousness that the idea had been inspired in him in a dream by supernatural forces. We will guarantee England her Empire; in return she will give us a free hand in Europe."

Unfortunately for Hess, his mission didn't exactly go off as planned. Out of fuel, he was forced to bail out of his plane near a farm in Scotland. He was eventually picked up by British soldiers, among them Brinley Newton-John, who helped to verify Hess' identity., reports the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Though he brought his message of peace to the British authorities, they regarded it as having no validity, and he was held as a prisoner of war.

He also helped break the German Enigma codes

Victory over Germany during World War II relied on one very important task — breaking the Nazi Enigma codes, in which all top-secret German communications were encrypted. These codes used a complex electrical device, known as an Enigma machine, that was thought to be unbreakable (via Britannica). Brinley Newton-John was part of the top-secret team that worked for months to prove them wrong.

The team worked alongside Alan Turing and others as part of the Ultra project at Bletchley Park, which eventually gave rise to the first modern computer. Newton-John's placement in the project had just as much to do with his musical talents as his fluency in German. As observed in the Daily Mail, "it was no coincidence that a number of professional musicians were employed at Bletchley — musical notation and codebreaking can easily go hand in hand."

Years later, talking with Ron Hurst of NBN Television, Newton-John would call his work with Ultra the "most significant" contribution he made to the war effort. "You can imagine what an immense advantage it is — particularly because, in the early part of the war, Britain was outnumbered, outgunned, out-everything — to know what the intentions of the enemy were ... without Ultra, we'd have had no hope of winning the war at all. None at all."

His intelligence helped the Allies defeat Rommel

Popularly known as the "Desert Fox," Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was considered one of the greatest military geniuses in Germany, and for months he had kept Allied forces in a stalemate in the Western Desert theater of North Africa.

It was not until October 23, 1942, that British forces won a decisive victory against Rommel, cutting off Axis forces from the Suez Canal and the oil fields of the Middle East, according to the National Army Museum and the Encyclopedia Britannica. While won with tanks, soldiers, and strategy, this victory might not have been possible without the intelligence provided by operatives like Brinley Newton-John working at Bletchley Park, who passed along information about German troop movements and supply lines to Allied forces prior to their strategic victory.

Stationed in what was known as Hut 3, where the intelligence decoded in Hut 6 was interpreted and analyzed, Newton-John was part of a team that had been gathering, decoding, and analyzing data for weeks leading up to the decisive battle. When the British forces met the Desert Fox at the Second Battle of El Alamein, it was this intelligence that helped to turn the tide against the infamous German tactician, as the Australian Dictionary of Biography recounts, describing Newton-John's contribution to the conflict.

In-between breaking codes, Olivia Newton-John's dad played Mr. Darcy

Of course, even spies and code-breakers need to unwind when they aren't interrogating prisoners of war or cracking German cyphers. Brinley Newton-John was merely one of several individuals employed at Bletchley Park who had a musical or theatrical background.

"There was a stage at one end of the large briefing hall," Ian Lowry, a Bletchley Park Guide, told the Daily Mail. "In his spare time, Brin acted on stage and performed in opera. He played the part of Mr. Darcy in 'Pride and Prejudice' and sang the part of the count in 'The Marriage of Figaro.' He was also a keen vocal member of the cast of many variety shows."

In fact, it was likely on that very stage in the Bletchley Park briefing hall that Newton-John recorded the aria from that opera that his daughter would listen to on "The One Show" more than 70 years later.

Brinley Newton-John became a professor of German literature

After World War II finally drew to a close in 1945, Brinley Newton-John had attained the rank of war substantive flight lieutenant, according to the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Not interested in pursuing a further career in the armed forces, he instead resumed the one that the war had interrupted, working as headmaster of the Cambridgeshire High School for Boys until 1954. He then moved his family from Cambridge to Australia to take a position as master of Ormond College at the University of Melbourne. Olivia Newton-John was just 6 years old at the time (as per her autobiography). Unfortunately, his marriage to Irene Born could not survive the rigors of both the war and the move to Australia, and within just a few short years it had broken up, leaving Irene to raise Olivia as a single mother.

Over the new few decades, Brin carved out an impressive career in academia, and by the time of his 1980 interview with Ron Hurst, he had served as deputy vice-chancellor the University of Newcastle. Following the breakup of his first marriage, Brinley Newton-John married twice more in the course of his life, and was the father of a son and daughter with his second wife, in addition to Olivia and her two siblings.

Olivia Newton-John was diagnosed with cancer the same weekend that her father died of it

By the time of his death in 1992, at the age of 78, Brinley Newton-John was often referred to as "the father of Olivia," due to his daughter's notoriety as a "world-famous pop star," as per the Australian Dictionary of Biography.

On the same weekend that Brinley was dying of cancer of the liver, Olivia Newton-John received the crushing news that she had been diagnosed with breast cancer, as she later recounted to Tim Teeman in an interview originally published in The Times. Even as she was getting the results and hearing the news about her father, she was preparing to embark on a world tour. Twenty years later, this experience helped motivate her to open the Olivia Newton-John Cancer and Wellness Centre in Melbourne.

"It had snuck up on him and the entire family," Oliva recounted in her autobiography. "One day, he was reading the paper and sipping his coffee, and the next day ... barely able to speak. ... In my heart, I knew I would never see my father again — and I was right."