The Untold Truth Of Skydiving

Skydiving is one of those crazy things on many people's bucket lists. Imagine the adrenaline rush skydivers must feel when they jump out of an airplane and fall back to earth, as their parachute glides them safely down. But there's much more to skydiving than that—for plenty of people, this is more than imagination or a vague fantasy. It's life, and it's awesome.

Skydiving has a surprisingly long history

You may think skydiving has only been around since the age of airplanes, but the concept has been around for thousands of years. Legend has it that the first skydive happened in ancient China around 80 BC, with an emperor fleeing a burning granary structure that his father set on fire and using "conical straw hats" tied together to descend to the ground. Not exactly Father of the Year material there, but this story showed an understanding of the principle behind parachuting, even if the story isn't true.

By the 1100s, Chinese were doing an early version of parachuting, jumping from structures. They used a device that was more like a parasol. Sounds like the predecessor to Mary Poppins.

Leonardo da Vinci sketched out a concept of a parachute

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) came up with a lot of ideas for inventions, but he didn't build many of them (he was known to be a bit of a procrastinator). This true Renaissance Man drew a sketch of what he thought a parachute could look like. It was shaped like a pyramid and would have used linens of the time. "If a man is provided with a length of gummed linen cloth, with a length of 12 yards on each side and 12 yards high, he can jump from any great height whatsoever without any injury," he wrote back then.

About 150 years later, a Croatian inventor named Fausto Veranzio was inspired by Leonardo and designed his own parachute, with more of a rectangular shape. He reportedly tested his design from various structures such as church steeples.

Then in 2000, skydiver Adrian Nicholas reviewed Da Vinci's original design and.decided to see if it really worked, His girlfriend Katarina Ollikainen followed Da Vinci's instruction and picture, using materials available in the 1400s, and Nicholas tested it out in the sky. It was a successful experiment. He floated for about 7,000 feet with it until reaching ground with a modern parachute.

Nicholas joked, "It took one of the greatest minds who ever lived to design it, but it took 500 years to find a man with a brain small enough to go and fly it." Ironically, Nicholas died five years later from a skydiving accident with a modern parachute.

In 2008, Olivier Vietti-Teppa took Leonardo's idea one step further. The Swiss man had a parachute made with modern materials but with Da Vinci's sketched design. However, he ditched Da Vinci's wooden frame idea. Vietti-Teppa, an amateur skydiver, jumped and made the first successful landing with the contraption. He called it "a perfect jump." The skydiver hasn't also tried to paint The Last Supper, though.

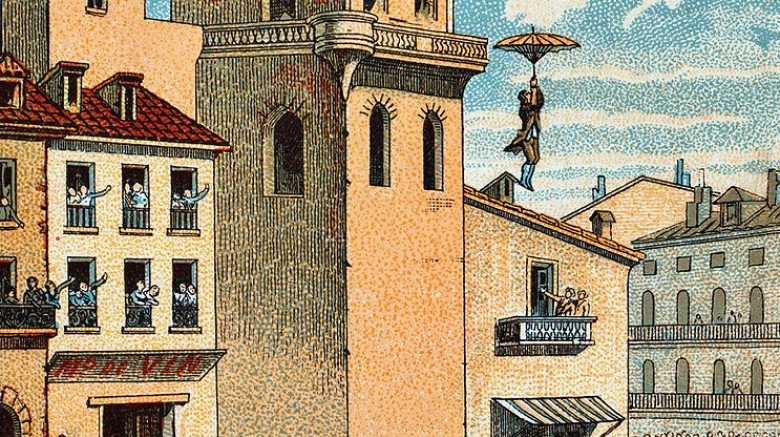

Before airplanes, skydivers jumped from anything they could get their hands on

Frenchman Louis-Sebastien Lenormand designed a parachute and jumped from trees and towers in the late 1700s. He thought of the device as something to be used for fire safety, so that people could get out of burning buildings.

The first relatively "modern" skydiver—as in jumping with a parachute from the sky—was Andre-Jacques Garnerin in 1797, who jumped from a hot-air balloon about 3,200 feet high. In later years, he would jump from as high as 8,000 feet and even skydive over the English Channel. There was a song written in honor of the channel crossing: "Bold Garnerin went up/That increased his Repute/ And came safe to earth/In his Grand Parachute." Well, at least it rhymed.

Planes got used for parachute jumps almost as soon as they were invented

It didn't take long from Wilbur and Orville Wright's first successful airplane flight in 1903 for parachutists to jump out of airplanes. Albert Berry, a US Army captain, had jumped from hot air balloons before, and is generally created as the first to jump from a plane in 1912. Legend has it that during the jump over St. Louis, Berry spotted an insane asylum and said to his pilot, Tony Jannus, "That's where we both belong." Good point. Jannus achieved a little fame of his own by becoming the world's first airline pilot.

During World War I, both England's Winston Churchill and America's Colonel Billy Mitchell separately thought of the idea to move troops by parachute, but the war ended before either of the ideas came to fruition.

Then in 1919, Leslie Irvin, once a Hollywood stuntman, became the "first American to jump from an airplane and open a manually open a parachute in midair," Smithsonian magazine notes. His use of a ripcord became the norm.

Pilots used parachutes in the 1920s as the way to survive a plane crash. There was initially some skepticism over whether pilots would have the presence of mind to deploy the parachute and if it would work, but after military test pilot Harold Harris survived thanks to his parachute in 1922, the Caterpillar Club was launched. People could only "join" the club if their life was saved thanks to a parachute. They would receive a gold pin in the shape of a caterpillar and also get a membership card from the Irvin Air Chute company, founded by skydiver Irvin. The club still accepts members today.

The Caterpillar Club's name came because parachutes of the day were made of silk. Charles Lindbergh was the club's most famous member. Ironically, Irvin himself was unable to join his own club. Even though he made over 300 parachute jumps, he never had to do it to save his life.

Paratroopers skydived in multiple wars

Starting with World War II, the US Army created airborne divisions of paratroopers and has used parachutes to drop people and supplies in every war since. One of the first big uses of paratroopers in the war was in Operation Husky, the 1943 invasion of Sicily. Then they were part of D-Day.

Paratroopers also landed in the Pacific theater, including in the Philippines and New Guinea. Since that time, the US military has used paratroopers to fight in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, making them the objectively most fun part of the military.

How paratrooping influenced The Twilight Zone

One paratrooper who alluded to in his war experiences in his writing proved to be enormously influential in pop culture. Twilight Zone creator Rod Serling was a paratrooper in the 511th Airborne who served in the Pacific. He was injured during the Battle of Leyte in 1944.

Serling also reportedly lost a friend while posing for a photo with him. A military plane dropped ammunition from the sky, and it landed on his friend and immediately killed him. Author Doug Brodie noted that "many 'Zone' episodes are about that split-second of fate where somebody arbitrarily gets spared or, absurdly, does not." The ammunition box was said to have "flattened [his friend] so fatally that he couldn't even be seen under the box." Now that sounds like something out of The Twilight Zone. No word on whether Serling ever went to a diner and saw the real Martian.

The TV legend survived that brush with death in World War II only to die at just 50 of a more prosaic cause. Remember how he used to smoke on The Twilight Zone and even did cigarette ads on the program? His horrible habit of smoking six packs of cigarettes a day was what killed him. He died after open heart surgery in 1975.

England had paradogs that parachuted on the shores of Normandy at D-Day

Not only did men jump out of airplanes in World War II, but so did dogs. ABC News said the pooches "were specifically trained to perform tasks such as locating mines, keeping watch, and warning about enemies." The War Dog Training School gave the dogs meat treats after the jumps and they also "served as something of a mascot for the two-legged troops," according to the network.

Dogs Bing, Monty, and Ranee parachuted into Normandy with Britain's 13th Battalion, but Monty was injured badly at D-Day and Renee got separated and was lost. Fortunately, two German shepherds defected and befriended Bing, assisting the Alsatian dog in his wartime duties. (Talk about a Pixar film waiting to happen!)

Bing helped protect his human brothers in arms by sniffing out dangers and later received the Dicken Medal, a medal the United Kingdom bestows on heroic animals. There's a statue of him at England's Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces Museum in Duxford, and a children's book about his amazing life. But no movie. Yet.

Skydiving is safer than you think

You might not be able to get a standard life insurance policy if you skydive, or you might have to pay more money for your policy. That's because life insurance companies still consider the sport too risky. And if you die from skydiving within two years of getting the policy, the contestability clause may not pay out the policy.

Yet in 2015, just 21 people died in the U.S. skydiving. If that seems like a lot, realize that was out of 3.5 million jumps, with about 500,000 of them people doing it for the first time. There were 1,920 injuries that year requiring medical attention. You're more likely to die getting stung by a bee than by skydiving. These numbers are even more amazing given that skydiving has been increasing in popularity, yet the death rate is getting lower.

Ironically, several skydivers have died not from skydiving but from plane crashes. In 1999, a Michigan skydiving plane crashed, and the nine skydivers aboard and the pilot all died. In 2003, four people died in a Pennsylvania plane crash related to skydiving.

In 2016, a plane in Hawaii burst into flames, killing the pilot, two jumpers, and two instructors. Also in 2016, a plane crashed into a house in Gilbert, Arizona. Fortunately, the pilot and the four skydivers survived, as did the people in the house. If your own plane starts to crash, and you happen to be lucky enough to be already wearing a parachute, we can only recommend you jump out sometime before the plane hits the ground.

You can skydive even if you are blind

You'd think you'd need to see to skydive, but you don't. Skydiver John Fleming gradually lost his eyesight to due to retinitis pigmentosa but was still able to skydive thousands of times. On the earth, he needed a guide dog, but in the sky, he just needed altimeters and two-way radios. In the video above, you can see him jumping with Dan Rossi, another blind skydiver.

You can also skydive if you're deaf or paralyzed. This can give a real sense of freedom to those who face disabilities on land. There's even a charity designed to help the disabled experience skydiving.

However, disabled skydivers face risks from skydiving as well, especially given the custom equipment they may need. One quadriplegic man died n 2011 after his parachute, which was custom-built for him, didn't open.

A few people have skydived without a working parachute and lived

Don't try this at home—or in the air.

In World War II, British RAF sergeant Nicholas Stephen Alkemade was a tail gunner whose plane was on fire. Both he and the parachute were burned. He said, "I had the choice of staying with the aircraft or jumping out. If I stayed I would be burned to death—my clothes were already well alight and my face and hands burned, though at the time I scarcely noticed the pain owing to my high state of excitement." Instead he "decided to jump and end it all as quick and clean as I could."

So he jumped 18,000 feet to land in Germany without a working parachute. Thanks to falling into some young pine trees and snow, he survived. He was captured by the Gestapo, though, who didn't initially believe his story. He told them to look for his discarded parachute harness. They did and finally believed him. The Germans even made him a certificate describing what happened, and he was treated as a minor celebrity. He survived life in the POW camp for the rest of the war and lived until 1987.

In the same war, American S/Sgt. Alan Magee was thrown from a burning plane (with the prophetic name of Snap! Crackle! Pop!) without a parachute. He reportedly fell through a railway station's glass roof and was injured but somehow survived. This was in France in 1943, when Nazis occupied the country. "I owe the German military doctor who treated me a debt of gratitude," the soldier said. "He told me, 'We are enemies, but I am first a doctor and I will do my best to save your arm.'"

A professional skydiver named Christine McKenzie survived an 11,000 foot fall in South Africa in 2004. Neither her main nor reserve parachutes worked. She crashed into some power cables and only suffered minor injuries. She had made 112 jumps at that point, and insisted she would do so again. Amazing.