The Crazy True Story Of Satirist Dorothy Parker

Only a handful of people in history are famous simply for their conversational skills. Dorothy Parker is on that very short list. As a co-founder of the legendary Algonquin Roundtable, Parker was renowned as much for her quick wit as her poetry, fiction, and work as a critic. Her pithy, satirical style was all booze-soaked Roaring Twenties attitude delivered with a raised eyebrow and a hilarious sense of comic timing.

One of the earliest examples of an "It" Girl, Parker was rebellious, fiercely intelligent, and so known for her witticisms she's routinely credited with quips and poems she didn't actually say. But the things she did say ensure her legacy—this is the woman who suggested that the epitaph on her gravestone should be "excuse my dust," and who once described the office she shared with lifelong friend and collaborator Robert Benchley as "an office so tiny, that an inch smaller and it would have been adultery."

But boiling down a life to a few sharp quips misses what truly makes Parker one of the most interesting people of the 20th century. Behind the hilarious lines and the sharp poems about suicide and social niceties, Parker was a fascinating woman who lived a pretty wild life. Here's the crazy true story of satirist Dorothy Parker.

This article contains references to suicide and attempted suicide. If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Her mother died when she was just 4 years old

Dorothy Parker was born Dorothy Rothschild in 1893 in her family's summer home in New Jersey, according to BBC Culture. She was largely raised in New York City, however—her father was a successful garment manufacturer, and the family had money. She described herself as "a plain disagreeable child with stringy hair and a yen to write poetry," and her childhood was not especially happy. According to the Los Angeles Public Library, her mother died when she was just 4 years old, leaving her to be raised by her father.

As noted by author Robert Sellers, Parker's father remarried shortly afterwards, and Parker didn't just dislike her new stepmother—she loathed her, refusing to call her anything but "The Housekeeper." Parker also hated her father and would imply later in life that he had been physically abusive towards her.

Saddest of all, according to author Cari Beauchamp, Parker's childhood was a lonely, depressing one. She was largely confined to the family's home in New York and was not allowed to do the typical things most children enjoyed. Lonely and trapped with a father and stepmother she disliked intensely, Parker said she "hated being a child."

She lost her uncle Martin on the Titanic

After losing her mother at the age of four, Dorothy Rothschild had more tragedy to come. When she was 18 years old, she lost her uncle as well. According to The Dorothy Parker Society, Martin Rothschild was among the more than 1,500 people who lost their lives when the RMS Titanic sank in the North Atlantic on April 15, 1912.

Martin and his wife Elizabeth lived just a few blocks away from Dorothy and her family in New York City. Author Richard Davenport-Hines reports that Martin had been in the garment business like Dorothy's father, and had traveled to Paris to inspect fashion houses with his wife. They purchased first-class tickets on the infamous liner.

The Encyclopedia Titanica reports that when the Titanic hit an iceberg and began to sink, Rothschild told a steward that his wife had departed on one of the lifeboats. She was later identified—along with her pet dog—as a survivor. Martin, however, was never seen again. Martin's death affected his brother deeply; Henry Rothschild was not working and in poor health already, and the shock of losing a brother he was very close to, proved to be too much. He passed away a short time later, leaving Dorothy alone in the world.

Dorothy Parker's first husband was a drug addict

As noted by BBC Culture, Dorothy Rothschild became Dorothy Parker when she married Edwin Pond Parker II in 1917 when she was 23 years old. Edwin was a successful stockbroker who lived a fast, wild life in New York. According to author Marion Meade, Dorothy found "Eddie" charming and irresistible in part due to his dim view of his own background and religion. Despite his heavy drinking, Dorothy fell in love.

Eddie was troubled, however. In addition to his heavy drinking, he became addicted to morphine. Life with Eddie was tumultuous and depressing. Even after Eddie successfully weaned himself off morphine, he simply began to drink even more heavily to make up for it. According to Literary Hub the marriage was effectively over by 1922 as the couple separated after Dorothy had an abortion, quipping "It serves me right for putting all my eggs in one bastard."

The Parkers remained officially married until 1928, when they finally divorced. Dorothy filed on the grounds of "intolerable cruelty" and Eddie didn't bother contesting. They never saw each other again after the hearing. Five years later, Eddie died of a drug overdose at the age of 39.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Dorothy Parker married her second husband twice

Dorothy Parker remained single for six years after her divorce; according to Literary Hub she "tried out" a long list of handsome young suitors during this period. Author Cari Beauchamp writes that one of these handsome young men was an actor named Alan Campbell, who quickly charmed Parker—they were married in 1934 when Parker was 39 and Campbell was 28. Parker didn't change her name.

Parker's relationship with Campbell was complicated. BBC Culture notes that aside from being 11 years younger, Campbell was also bisexual, and there were rumors of infidelity on his part. They were both heavy drinkers, and seldom seen without a drink of some sort in their hands. Yes despite all that, according to Spartacus Educational, Campbell provided Parker with stability: He took care of the housework and worried over her, giving her the time and space to work on her writing.

The couple moved to Hollywood where they had success as a screenwriting team. They were married for 13 years, and then Parker had an affair with a young actor named Ross Evans and divorced Campbell in 1947. When Evans dumped Parker, she contacted Campbell and they remarried in 1950. By the early 1960s the marriage had crumbled again, and they separated. Sadly, as reported by The Dorothy Parker Society, Campbell died of an apparent suicide in 1963, when he was just 59 years old.

Condé Nast fired her

Dorothy Parker's talent for writing and wit was obvious. BBC Culture reports that she got her first break when editor Frank Crowninshield bought a poem she submitted to Vanity Fair in 1914. She was soon a staff writer at the magazine (she also wrote for Vogue) and the resident theater critic known for her caustic wit and a blistering honesty about the plays she reviewed.

When Condé Nast hired Robert Benchley and Robert Sherwood as well, not only were the seeds of the famous Algonquin Roundtable planted, but all discipline in the office was soon lost. According to author Susan Ronald, they were terrible employees. Parker admitted that the trio behaved "extremely badly," indulging in endless booze-soaked lunches and spending most of their time in the office goofing off and chatting.

But Parker and Benchley were talented enough to get away with it—until Parker's penchant for witty putdowns crossed a line. As reported by The Public Domain Review, Parker piled withering insults on actress Billie Burke's performance in a play called "Caesar's Wife." Burke's husband was the influential Florenz Ziegfeld, who demanded that Parker be fired. Her termination was a scandal (Benchley and Sherwood resigned in protest), and Parker never held a steady job ever again.

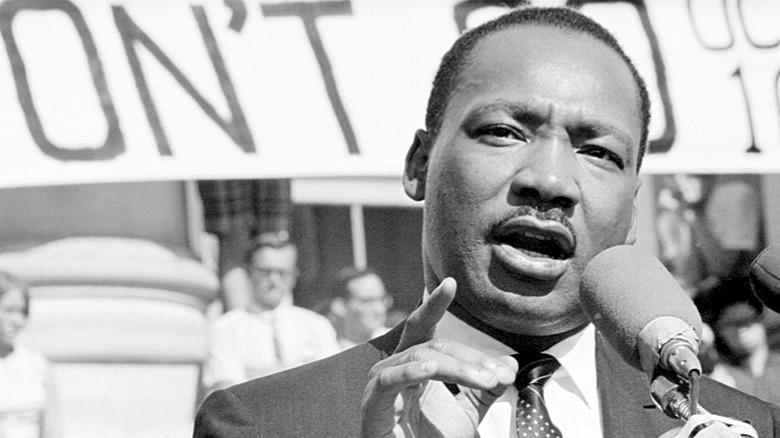

Dorothy Parker was a passionate fighter for civil rights

When Dorothy Parker died in 1967, The Human Rights Warrior notes that her small estate was bequeathed to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., simply because she admired him (the two had never met). When King was assassinated a year later, her estate passed to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which still receives royalties from her book sales.

This wasn't a random decision. Behind her cocktail hour wit and caustic poetry, Dorothy Parker was a passionate advocate for civil rights and racial equality. According to Vanity Fair, she became aware of the horrible inequities in life as a child of some wealth in New York City. The Guardian reports that her lifelong efforts fighting racism and fascism are often overlooked, but Parker spoke out against prejudice frequently, founded the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (at a time when Adolph Hitler and the Nazis were still admired in some circles), and raised money for refugees.

Most notably, according to The New Yorker, Parker founded a committee dedicated to assisting the Scottsboro Boys, nine Black men falsely accused of raping two white women in 1931. Parker spent much of her life working to make the world a better place, and her legacy should be focused on that as much as her writing talent.

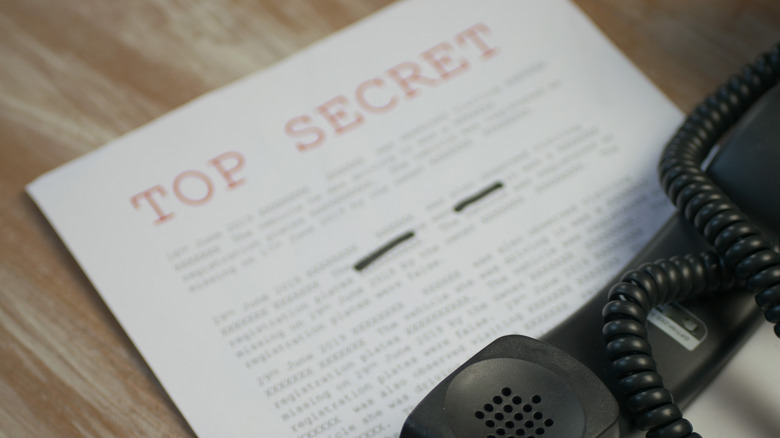

The FBI kept a file on Dorothy Parker

When not delivering devastating one-liners with a cocktail in her hand, Dorothy Parker was surprisingly political. As noted by Literary Hub, she founded the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, was arrested at a left-wing protest against the execution of anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, and visited Spain during the Civil War. And as noted by The Dorothy Parker Society, she co-founded the screenwriters union (the modern-day Writers Guild).

Of course, those politics are decidedly liberal—and as the McCarthy Era rolled over the United States in the 1950s that made Parker a target. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Parker wasn't a communist—but she had friends who were involved with communist causes, and she wasn't shy about supporting them, often showing up at congressional hearings. As a result, Parker was not only tracked and surveilled by the FBI, but she was also blacklisted by Hollywood, going from one of the highest-paid screenwriters of her day to someone who couldn't find work anywhere.

The FBI officially exonerated her of "un-American" activities in 1955, but the damage to her career had been done. Surprisingly, the FBI kept large portions of her file confidential for decades until a Freedom of Information Act request finally unsealed them in 2018.

She suffered from serious depression

One of Dorothy Parker's most famous poems is the short, pitch-black "Resumé," perhaps the darkest eight lines ever composed, briefly outlining various ways someone might try to end their life, and deciding that they all have downside so "you might as well live." Far from a witty work of imagination, Parker was, sadly, working from grim experience: She attempted suicide several times over the years. As noted by The Los Angeles Times, not only was Parker an alcoholic battling depression, she also disparaged her own literary legacy and desperately wanted to be an "important" writer. Dwelling on her perceived professional failures often combined with a disastrous love life—the perfect recipe for despair.

According to Literary Kicks, Parker first attempted suicide at the age of 29 after a messy extramarital affair. The Dorothy Parker Society reports that Parker attempted suicide again in 1932 after breaking up with a lover named John McClain. There was a pattern to Parker's behavior: A love affair, a breakup, depression, and an attempt to end her life. Then she would pull herself together and repeat the pattern again.

Despite her many attempts to end her own life, The New Yorker reports that Parker lived to be 73 years old, dying in 1967 of a massive heart attack.

Dorothy Parker was an alcoholic

While the popular image of Dorothy Parker is a sharp-witted modern woman perpetually holding a cocktail glass in one hand, the truth is a bit darker. As noted by BBC Culture, there is little doubt that Parker had a serious drinking problem and was very likely a full-blown alcoholic, at least later in life. She self-medicated aggressively, quipping that she wasn't a writer with a drinking problem, but a drinker with a writing problem.

But as Encyclopedia.com reports, by the 1940s her drinking had gotten out of control. In 1942, she was drinking so heavily she checked herself into a sanitarium in order to dry out. According to Cycles of Change Rehab Center, Parker was as sharp as ever, informing the doctors that the room was lovely but she would need to leave every hour to go get a drink. When the doctors warned her that if she didn't stop imbibing she would be dead in a month, she responded, "Promises, promises."

The primitive substance abuse treatments of the times weren't very effective, however, and author Marion Meade notes that Parker was never completely convinced that she had a problem, which made it impossible for her to effectively deal with her substance abuse issues. She continued to drink heavily until she passed away in 1967.

Dorothy Parker spent her final years alone and lonely

The popular image of Dorothy Parker is the life of the party. This is the woman who co-founded The Algonquin Round Table, after all, spending her evenings minting savage quips and playing a high-stakes game of conversational chicken with some of the smartest people around. She married two different men and according to The Guardian was one of the highest-paid screenwriters in Hollywood (she co-wrote the original version of "A Star is Born"). That doesn't sound like a lonely life.

And yet that's exactly how it ended. According to Literary Hub, her second husband (technically also her third—they divorced in 1947 and remarried in 1951—died in 1963. Although they'd been separated for several years by that point, this sad event prompted Parker to move back to New York City. She moved into a small hotel in Manhattan where she lived alone with her dog.

The saddest part of these final years, as noted by BBC Culture, is that if she managed to publish some writing the main reaction she received from the public was surprise that she was still alive. Most of her old friends had died. Always terrible with money, she was basically broke, and relied on the generosity of the few friends she had left. Worst of all, Parker felt like she'd failed to achieve anything of worth with her writing and went to her grave disappointed and lonely.

No one claimed Dorothy Parker's ashes

According to The Guardian, Dorothy Parker struggled for money in her final years, and relied on the assistance of friends like fellow writer Lillian Hellman for survival. Hellman was under the impression that Parker would compensate her in her will when she passed away. According to The New Yorker, Parker's estate was worth just a little over $20,000, but her books still sold, so there was considerable future income to consider.

But when Parker passed away, her will didn't leave anything to Hellman except duties: Hellman was named executrix of Parker's estate, but got exactly zero in terms of money—Parker left everything to Martin Luther King Jr.—and in the event of his death, to to the NAACP. Hellman was enraged, and not only disobeyed every instruction in the will, but tossed almost all of Parker's possessions into the trash. And in a final, petty move she didn't bother to pick up Parker's ashes after her cremation. They remained at the crematory for years and were finally sent to Parker's lawyer, who kept them in a filing cabinet. After 20 years, the NAACP claimed them and interred them in a memorial.

The Seattle Times reports that Parker's ashes were only transported to her family's plot in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx in April 2021—and she finally received a tombstone, more than 50 years after her death.

Dorothy Parker felt like a failure

Dorothy Parker was an incredibly gifted writer. Aside from her legendary wit, Britannica reminds us that she wrote best-selling books, poetry that is still recited and short stories that are still discussed today, and reams and reams of delightfully arch criticism and commentary for magazines like Vanity Fair, Vogue, and The New Yorker. She also had writing credits on more than 15 films, including "A Star is Born," which earned her an Academy Award nomination.

And yet, according to the National Endowment for the Humanities, Parker died convinced she was a failure because she had not published a novel. Parker was convinced that a novel was the sign of a true creative writer, and her failure to produce one haunted her. According to The Guardian, she even came to disparage her most famous creation—the Algonquin Round Table, where she lorded over some of the brightest people in the world for a time in the 1920s and 1930s. Towards the end of her life she described that famous informal club as a "bunch of loudmouths."

Parker's lack of a novel wasn't due to laziness, but the opposite: As noted by author Adrienne Crezo, writing was difficult for Parker. A perfectionist, she worked word-by-word, once saying that "I can't write five words but that I change seven." In 1929, she signed a contract with Viking Press for a novel—after her death, the company announced it was the longest unfulfilled contract in the company's history.