The History Of Cremation Explained

Dealing with the death of a loved one is hard, and it's sometimes made all the more difficult when it comes time to consider practicalities. Funeral or memorial? Should you have a wake? Flowers or no flowers? And, perhaps most pressingly, what exactly are you supposed to do with the body that's left behind?

Throughout history, that question has been met with a simple answer: cremation. While there are plenty of cultures and religious traditions that practice burial (also known as "inhumation") or other methods of managing the dead (like the Zoroastrian practice of excarnation in a Tower of Silence, per Slate), cremation is an increasingly widespread tradition today.

How popular is cremation nowadays? Depending on where you live, it's one of the most frequently-picked options. As CNN reports, in the United States it became the most popular method of dealing with a person's remains in 2015 and has remained at the top of that ranking ever since then. And it's already a widely established practice in quite a few other cultures, with more than three-quarters of people in India using cremation and a nearly 100% cremation rate in Japan, according to the Neptune Society. But how did this practice get here? This is the history of cremation explained.

Cremation is very, very old

Lest you think that cremation is new, archaeological evidence uncovered from Australia shows that humans have been cremating their dead for a very long time.

The site in question, located in the eastern Australian state of New South Wales near Lake Mungo, contains evidence for cremation dating back to the Pleistocene era, according to the journal World Archaeology. The site, dated to around 25,000 to as far back as 32,000 years ago, contained evidence of human habitation, discarded stone tools, and human remains that had been pretty clearly subjected to an extensive fire. What's more, the bones appear to have been further broken down by smashing after the cremation.

That last step may seem a bit brutal to some, but even modern cremations involve a step where crematory workers must pulverize the remains into a fine, consistent powder (via Cremation Association of North America). The Plesitocene people were, however, not quite as strong as modern machinery and left behind enough remains for 20th century archaeologists to make some identifications. According to World Archaeology, the bone fragments left behind at the Lake Mungo site were clearly identified as one individual, known as "Mungo I," as a young female. Once the cremated remains were sufficiently broken down, the ashes and bone fragments were deposited in a burial close to the fire.

Many cultures have a long history of cremation

While it's clear that humans have been cremating their deceased compatriots for many thousands of years, it would take a bit longer for textual evidence of this practice to come along. According to Encyclopedia.com, ancient Greece tended to reserve cremation for soldiers, an honor that's described in both the "Iliad" and the "Odyssey" by ancient poet Homer. Ancient Roman emperors, who were typically interested in cementing their godlike status throughout their lives, were also often cremated to emphasize their ascent into godhood.

Yet, it's really in Asia where cremation has some of its deepest-held roots. In Hinduism, the practice is linked to reincarnation, as it can be seen as allowing the spirit that once inhabited the body to move on to its next life. Cremation is also popular in Buddhist groups, especially since the Buddha himself was said to be cremated after his own death, which occurred at some point between the 6th and 4th centuries B.C.E. (via Britannica). Then again, as the Neptune Society notes, there's a fair amount of variation amongst the different Buddhist sects out there, meaning that cremation, while popular, isn't necessarily a requirement within the widespread and diverse religion.

Vikings had unique cremation traditions

When it comes to death customs, the Vikings are pretty well known for what's commonly called a "Viking funeral." You probably already have a picture of it ready to go in your own mind — a dead warrior in the middle of a longboat, probably laden with treasure or goods. The ship is set adrift and then, with a flaming arrow, set aflame. But did this really happen?

Not quite. As History reports, Vikings (also known as the Norse people) had a variety of ways in which they honored the passing of their dead. Those practices can generally be broken down into two broad categories: cremation and burial. Burial could mean anything from a simple grave to grandiose burial mounds that could include treasure and even whole earthbound ships (via University of Cambridge). Cremation more often took place on a pyre and very rarely involved sending a very expensive longboat out to sea, only to be burned.

Though the Norse didn't seem too bothered about picking between the two burial rites, there is textual evidence that cremation was pretty popular. In the Ynglinga Saga, written in the 12th century according to Britannica, it was given the thumbs-up by the head god, Odin. As the saga notes, "Thus he established by law that all dead men should be burned, and their belongings laid with them upon the pile, and the ashes be cast into the sea or buried in the earth."

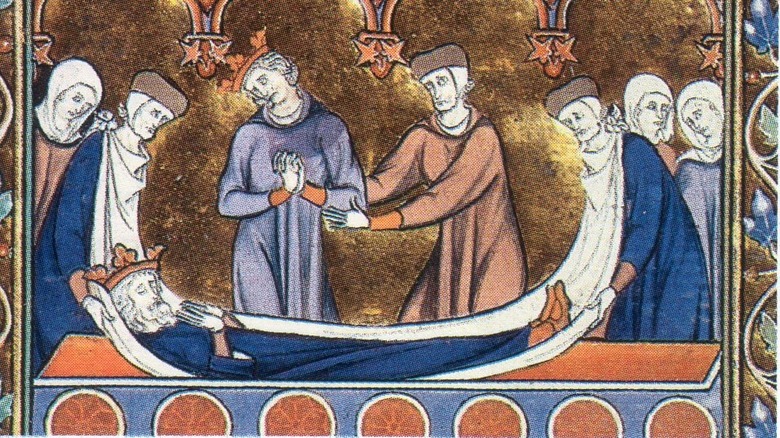

Medieval Christianity strongly discouraged cremation

Though plenty of cultures throughout humanity's history have been in favor of cremation, a few others have been utterly horrified by the idea. And if you were to travel to medieval Europe and suggest such a thing, you may well have been faced with mortal peril yourself.

According to The Guardian, by the time the Middle Ages rolled around, Christians in Europe were thoroughly committed to burying their dead. Their reasoning was that, upon the faithfuls' resurrection at a future point, they would need their physical bodies. That's why the people who were deemed too sinful for society — like witches or people who died by suicide — were buried outside of consecrated graveyards. And at least they were buried, though the lack of a priest-led funeral probably wasn't all that comforting. Either way, a pile of cremated ashes and bone fragments simply wouldn't do.

For good Christian folk, cremation was also associated with the godless pagans. "A History of the Church" notes that, during the eighth century in Saxon territory, those who went ahead and immolated their dead could face serious consequences that reportedly included their own deaths. To avoid such a fate, they would have to fall into the orthodox line, which included going to church, getting baptized, and tucking their dead folks away underground.

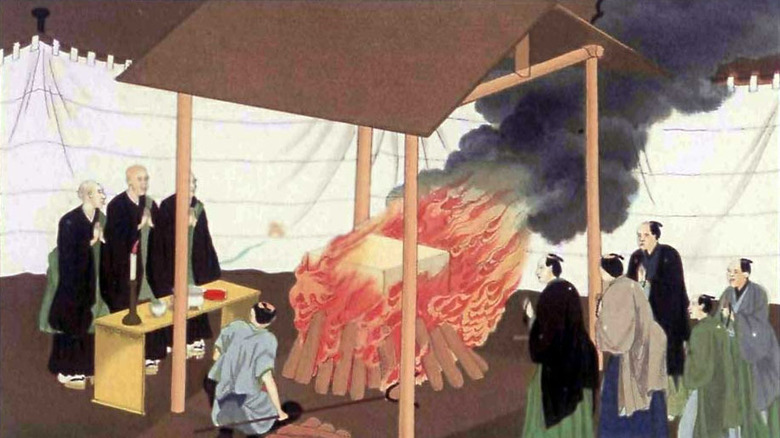

Japan has a long and complicated history of cremation

Throughout much of its history, Japan has been pretty on board with cremation, especially since so many of its people have practiced cremation-friendly Buddhism over the years, according to JSTOR Daily. It also helped that cremation was widely seen as a hygienic practice, dramatically and thoroughly getting rid of any potential contamination (physical or spiritual) that a dead body represented. Two prominent eighth century figures, including Emperor Jito, were also cremated, making for an even more popular practice.

Yet, things weren't all copacetic on the funerary tradition front. Confucianists pushed back against what they thought was an "unnatural" practice that, to their minds, was actually causing pollution and not helping fight it. And though Confucians remained something of a minority in Japanese religious life, they did gain a stronger foothold in the upper classes, to the point where members of the royal family began to choose internment over the pyre.

With the Meiji era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries came a desire to "modernize" (that is, Westernize) Japan. For many, this meant discarding the old-fashioned Buddhist practices like cremation. It was even banned in 1873, though the edict was repealed only two years later. As time has moved on, increasing population pressures and, frankly, less space for buried bodies and for families to visit remains, cremation made a significant comeback in modern Japan.

Intellectuals and revolutionaries brought cremation back to Europe

Back in Europe, it took quite a while for things to swing around in favor of cremation again. There were, after all, centuries upon centuries of Christian orthodoxy to deal with, all of which saw the burning of a body as essentially sacrilege. But, as the Architectural Review argues, things began to change as European colonizers made their way into territories that were still cool with cremation, like India.

More progressive and science-minded folks began to show interest in the practice as the 19th century moved forward, though they were still met with considerable resistance from both the church and governmental authorities. It got to the point where some aspirational cremators were arrested and put on trial. One 1884 case in England found that there was no real legal reason why people couldn't take it on, furthering the cause of the Cremation Society of Great Britain.

Cremation got especially popular amongst those who wanted to step away from the strictures of the Christian church, too. How Stuff Works notes that, during the French Revolution, quite a few people leaned into cremation as a way to have a church-free funeral.

Cremation was presented as a solution to a public health problem

The growing interest in and public acceptance of science in the 18th and 19th centuries helped push Europeans ever closer to accepting cremation. And while few people seemed ready to give up their relationship to their Christian religion or to the church, other avenues proved more compelling. Namely, public health matters became a big deal.

According to JSTOR Daily, 19th century cremation advocates presented their preferred method as one of the safest ways to dispose of a body. This was, after all, a time following a long era during which pandemics, mass graves, and steadily crowded graveyards meant that many were confronted with decomposing remains. Some horrified onlookers couldn't help but see the evidence of packed churchyards, which sometimes demanded that gravediggers stack coffins, reinter bones, and generally move around what was supposed to be someone's final resting place (via The Guardian). Doctors at the time even blamed cholera outbreaks on nearby mass graves, worrying about contamination in nearby soil and local water supplies.

A lot of this advocating rests on miasma theory, a now pretty thoroughly debunked idea that says harmful vapors arising from corpses could cause disease in living people, as the "Encyclopedia of Cremation" reports.

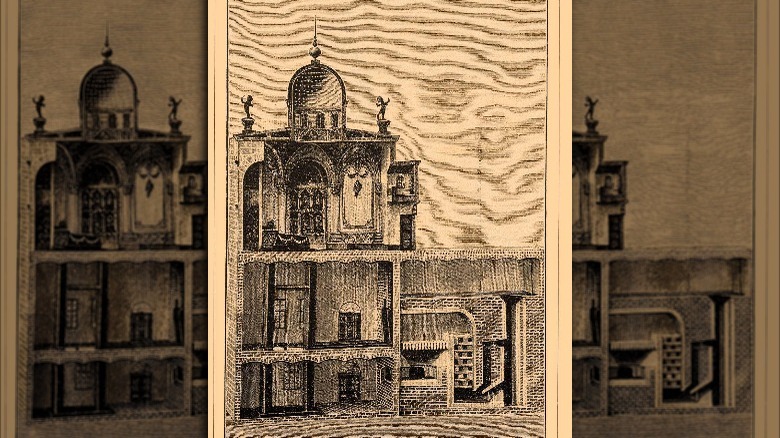

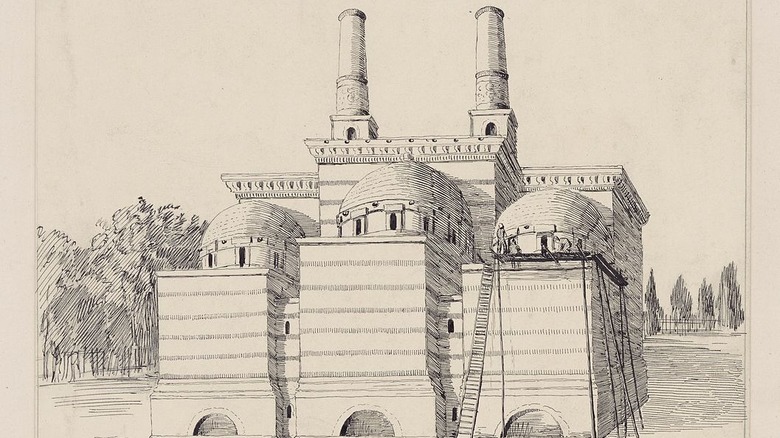

New technology helped pave the way for modern cremation

Arguably, part of the reason why it took so long for cremation to catch on in some cultures is the fact that, to thoroughly break down a body, the flames must run very hot for a very long time (via How Stuff Works). For a person who may have died in a rural European village or a crowded city center, there simply weren't facilities available to do more than singe their remains. Burial was simply easier, at least as long as there was still room in the local graveyard.

Then, technology came along and changed everything. But it wasn't without some initial struggle, as the Architectural Review reports. Early crematoria designers had to figure out where to place furnaces and chimneys for both maximum effort and to hide these necessary structures from mourners.

These structures and needs were refined over the years, making cremation a progressively more efficient and modernized process. According to Encyclopedia.com, more and more technology, like cremulators for processing leftover bone fragments into a more visually acceptable powder, helped things along considerably.

The first cremation in the United States was a big deal

In 1876, cremation advocates performed what's been widely recognized as the first modern cremation in the United States. Given how popular cremation has become since then, it may come as a surprise to learn that this first cremation was so unusual that it attracted a crowd of reporters.

According to Atlas Obscura, it ironically began, more or less, with the remains of one Joseph Henry Louis Charles, a minor European noble. Charles wasn't just a rather forward-thinking member of society who was interested in Asian funeral practices; he also apparently harbored a phobia of being buried alive. Cremation offered a pretty definitive way to avoid that haunting prospect.

Yet Americans, like their European counterparts, were reluctant to discard centuries of burial tradition to watch a corpse go up in flames. Anti-cremation people also argued that the practice could destroy evidence needed for later criminal trials and pooh-poohed the idea that decomposing bodies were a health hazard. Yet, cremation advocate Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne persisted with his plan to cremate Charles, building a crematorium on his own private property. And, though the reporters who gathered the day of Charles' cremation were rather sensationalist in their coverage, it turned out that LeMoyne was betting on the right side of history, after all.

The Catholic Church was slow to accept cremation

While more and more Christians were beginning to come around to the idea of cremation by the dawn of the 20th century, there were still a few holdouts. And most vocal amongst them were members of the Catholic Church. A 1908 entry on the subject in the Catholic Encyclopedia seems to start off equitably enough, but then makes its writers' skepticism plain for all to see. They lean pretty hard on the matter of resurrection, in which they believed a full human body (presumably restored from the effects of decades- or centuries-long decomposition) was necessary to join Christ upon his return.

While entry writers admitted that there was technically nothing in church doctrine that said you couldn't cremate someone, it was nonetheless a "sinister movement" that pushed Catholics to compromise their faith (and was maybe linked to worldwide government domination, while they were at it).

Yet, in the decades since, things have changed considerably. According to CNN, the Catholic Church is now officially okay with cremation, though the Vatican has set out rules that disallow some now-common practices like scattering of ashes.

Cremation is linked to increased urbanization

For many, cremation became more and more acceptable not because of theological shifts or cultural reconsiderations. Instead, matters of practicality took to the forefront. Or, in more plain language: What else are we supposed to do with all these bodies?

The rather bald fact of the matter is that, though they are relatively quiet and tend to mind their own business, human corpses still take up space. Burying them whole may seem comforting and is certainly traditional in many cultures, but modern communities are coming up against the issue of crowded graveyards. Of course, that's been a topic of debate for centuries, given that some communities have routinely disinterred old sets of remains when it's time for new inhabitants to take occupancy in a grave (via Atlas Obscura). Modern people have to grapple with the issue even more increasingly, according to The Guardian.

So, it makes sense that cremation is more and more a hallmark of densely packed urban environments. That's one of the reasons put forth as to why so many people in highly urbanized Japan prefer to be cremated, according to JSTOR Daily. Meanwhile, Encyclopedia.com suggests that increasing commercialization, which helped many detach themselves from the immediate nature of death by outsourcing end of life duties to funeral industry professionals, also pushed for increased cremation rates.

A few modern scandals have marred cremation's reputation

Though cremation is now a pretty routine practice, there are still some issues with the process. But it's not the fault of the deceased or the furnace, for instance — most often, it has to do with the people who are tasked with running a crematorium.

As How Stuff Works reports, unscrupulous crematoria operators and a surprising lack of laws led to some serious issues. In 2002 Georgia, many were shocked to learn that the Tri-state Crematorium had been discarding bodies in various outbuildings and even amongst some nearby woods. Years ago, their furnace had malfunctioned and, instead of repairing it, operators had simply been collecting fees and giving families urns full of materials like cement and ash. Georgia lawmakers eventually formalized laws that criminalized this treatment and required all crematoria in the state to be fully licensed and regularly inspected.

More recently, a Colorado funeral home was subject to charges that the operators had been doing something even more blatantly unethical. NBC News reported that the Sunset Mesa Funeral Home in Montrose, Colorado, was allegedly at the center of an attempt to sell human body parts for scientific and educational markets. The sources were human remains that families believed were already cremated, meaning that operators Megan Hess and Shirley Koch never bothered to get anyone's permission (and collected all the funds for themselves). The pair were indicted on federal charges in 2020.

Disposing of cremated remains today can get complicated

For some people, a major point of cremation is the ability to keep a loved one's remains close by, perhaps on a mantle or in a cabinet in their home. Yet, upon receiving ashes, other families still wish to dispose of the remains. But, assuming that they want to do so in a way that makes all of their local and federal lawmakers happy, things can get kind of complicated.

How Stuff Works notes that there are a few different options. Some might deposit cremated remains in a columbarium, a dedicated building or space meant to house many individuals' ashes. But that's a choice that is apparently pretty low in popularity, as many more choose to keep urns at home or even take a halfway step of burying them in a grave. As for those who want to scatter their loved one's ashes, they'll have to check with local regulations and may have to complete a stack of paperwork first. And, for anyone considering an at-sea ceremony, the Environmental Protection Agency demands that it be done at least three miles offshore in most cases.