The Untold Truth Of The Statue Of Zeus At Olympia

Everybody has heard of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but few people can name them all. Nevertheless, the idea captures the imagination of modern people. The World History Encyclopedia explains that the first list of the ancient wonders was compiled by Philo of Byzantium in 225 B.C. in his work, "On the Seven Wonders." Philo called these wonders "themata," which translates to "things to be seen." This list contained the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, and of course, the subject of this article — the Statue of Zeus at Olympia. Perhaps what makes the Ancient Wonders even more intriguing for modern people is that, sadly, all of them are gone except the pyramids.

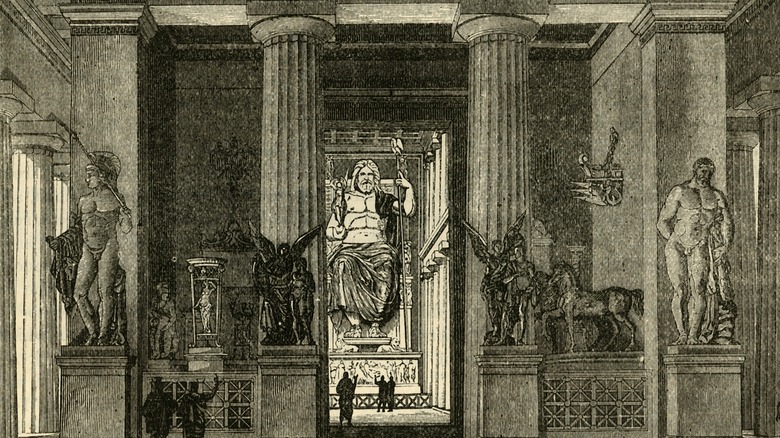

Of the Wonders, the statue of Zeus at Olympia has one of the most interesting histories. Linked to the sport and religion of the ancient Olympiad, it thrived as long as the Olympics thrived. Although we now regard the statue as one of if not the finest examples of ancient Greek monumental sculpture, the truth of the matter is that we are not even sure what it looked like. Let's begin by looking at why Olympia was so important that the Greeks dedicated an immense statue to Zeus there.

Olympia had sacred significance for the Greeks

In a valley within the Greek Peloponnese, there is an ancient site that was sacred to the ancient Greeks. By the 10th century, this region — now a UNESCO world heritage site — became the center of worship for the chief Greek deity, the sky-god Zeus, and other gods of the Greek pantheon. The central locus of Zeus worship was known as the Altis, which was described by UNESCO as a "sanctuary to the gods." "Olympia: The Story of the Ancient Olympic Games" explains how this district was held so sacred that the ancient Greeks consecrated a significant number of temples there.

First, there was one temple dedicated to Hera in 6 B.C., and then in the next century, a temple was dedicated to Zeus. There was also a temple to Rhea, the mother of Zeus, as well as a shrine to Pelops. The area was also lined with collonades and built to provide many anticipated visitors shade. In addition to these ruins, the region is also home to a number of ancient treasuries, making it perhaps one of the most important places for our understanding of Greek religion and culture. As the International Council on Monuments and Sites stated, "The renown and universal value of Olympia are so evident that it would seem superfluous to justify them."

The statue was built to help tourism

Olympia is most well known as the home of the ancient Olympic Games, which were the most important cultural event to the ancient Greeks and part of a religious festival to honor Zeus. According to the World History Encyclopedia, these games ran every four years from 776 B.C. to 393 A.D. for a total of 293 consecutive Olympiads before they were banned by the Roman Emperor Theodosius.

The games grew in popularity after their inception. The Olympiad was a chance for the Greek city-states to compete peacefully and show which one of them was the best. Elis, the city-state that usually controlled Olympia, saw the Olympics not just as a religious festival but also as an important opportunity to draw thousands of people to Olympia for the economy. Even in off years, pious Greeks were drawn to the Altis. What better way to draw in more pilgrims and more drachmae than by building a new fabulous temple to Zeus complete with one of the finest statues ever produced by humanity? What is more, "The Temple of Zeus at Olympia, Heroes, and Athletes" states that Elis had just conquered its rival neighbor Pisa and was looking to spend some of the loot. So Libon of Elis was commissioned to build a huge Doric temple between 460 B.C. and 457 B.C., and all it needed was the pièce de résistance — the statue itself.

The statue was crafted by the master of ancient Greek sculpture

As noted by Britannica, Phidias (or Pheidias) was a master sculptor and artist from Athens who lived roughly between the years 490 B.C. and 430 B.C. Phidias was responsible for building numerous renowned artistic works, including the Parthenon frieze. The temple housed several monumental sculptures of the goddess Athena, including a massive one that is the most famous. Phidias and his assistants were also responsible for much of the other sculptures of the Parthenon, including the famous Elgin Marbles, and its ownership remains debated to this day. Sadly, none of Phidias' work exists anywhere in its original form. However, proximate copies of the work were made in ancient times and passed on to today, which gives us a sense of this artist's once-in-a-millennium talent.

Phidias ran afoul of Athenian authorities in the last years of his life. Notably, he was accused of stealing gold from the statue of Athena. However, as "Zeus: A Journey Through Greece in the Footsteps of a God" relates, the sculptor was proved innocent after they removed the statue's gold and weighed it. His enemies then accused him of impiety for placing a sculpture of himself with Pericles on the statue's shield. It was once believed that Phidias died in prison, but in actuality, he ended up in Olympia, where he received the commission to build the statue of the mighty Zeus.

The statue had a monumental temple around it

Before we dive into details of the statue itself, let's look at the temple, since the ancient Greeks considered temples to be the domiciles of the gods. The World History Encyclopedia explains how the temple to Zeus at Olympia was the largest in the ancient Greek world. At its tallest elevation, the temple was 65.5 feet high and covered over 19,000 square feet sporting six by 13 Doric columns. "The Temple of Zeus at Olympia, Heroes and Athletes" notes that the pediments of the temple detailed athletic scenes of racing and wrestling based on well-known myths. The western pediment featured a myth of centaurs battling the Lapith people, while the eastern pediment featured a mythical chariot race between Pelops and Oinomaos; Pelops won, but he cheated.

It seems clear that these particular subjects were selected for the benefit of the athletes of the Olympiad who would gather in front of the temple. However, it's unclear what message was trying to be imparted by showing a chariot race involving cheating. To further encourage the athletes, the colonnade sported scenes from the Twelve Labors of Herakles.

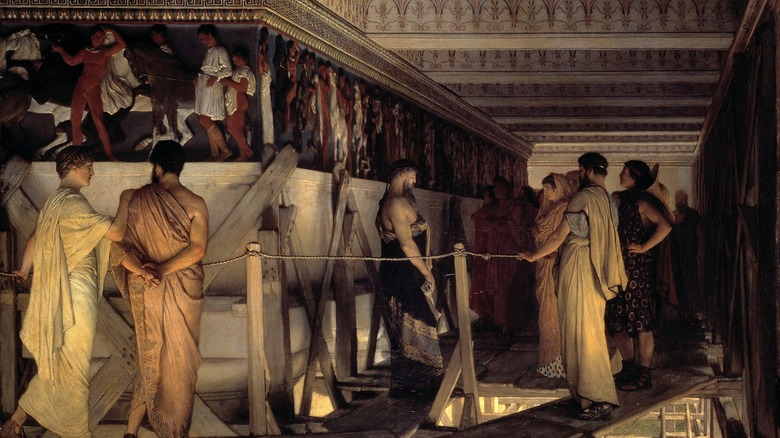

The Statue of Zeus was based on a wooden core

With the temple ready to receive its sculpture, all eyes turned to Phidias. According to the University of Chicago, the sculptor set up his workshop across from the temple. To ensure that the statue was built to the correct scale, Phidias had his workshop built to the dimensions of the temple's cella — the inner chamber where the statue was to reside. Twentieth-century archaeological findings hint at how the statue was made and also revealed Phidias' drinking cup, which sported the message, "I belong to Phidias" (via Ancient Greece).

It may come as a bit of a surprise to those who are unfamiliar with monumental statues, but the statue of Zeus was not of one piece. Instead, the work — like the one of Athena in the Parthenon — was to be chryselephantine. According to Britannica, this technique used ivory for the flesh and gold to drape the figure's form. To start, Phidias and his assistants used a wooden core over which they wrought and fitted pieces. Indeed, the terracotta moulds that were found by archaeologists in Phidias' workshop were probably used to shape glass into the fold of the god's robes. Eventually, these individual pieces were likely carried over to the temple and reassembled as a monumental god seated upon a throne.

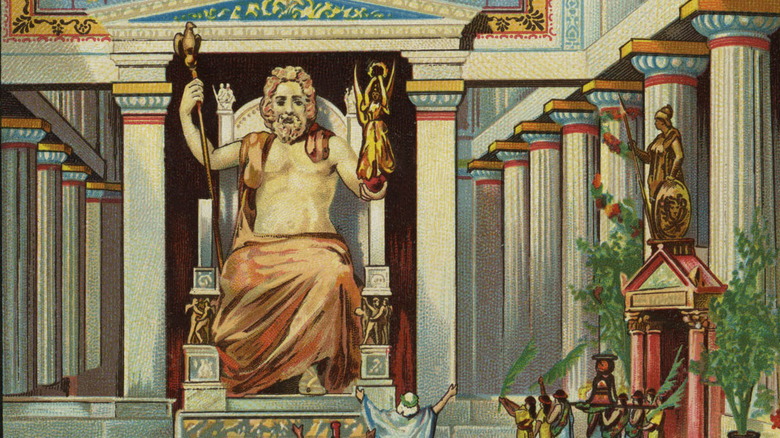

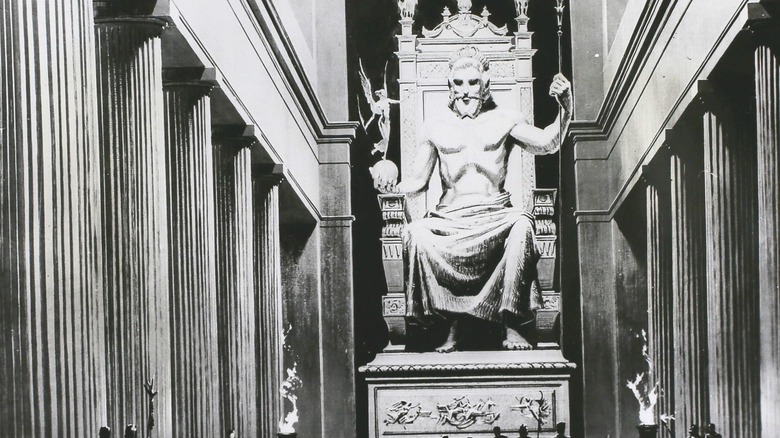

The Statue of Zeus was monumental

The end result was a colossal statue that awed virtually everybody who saw it. "Statue of Zeus at Olympia" quotes Strabo the ancient geographer as writing that the statue's "size was so great that, even though the temple is very large, it seemed as if the artist, in having him seated got the proportions all wrong, since he almost touched the roof with his head, giving the impression that if he were to stand up straight, he would dislodge the roof of the temple." Surprisingly, the exact dimensions of this statue are not known. Ancient sources state that the dimensions were recorded, but those recordings have been lost, leaving modern scholars to use inference and archaeology to figure out the truth. Generally, most sources will state that the statue was about 40 feet high, per Britannica.

According to the World History Encyclopedia, Zeus' skin was all in white ivory. However, his robes, beard, and staff were covered with sheets of gold. Other details were wrought using silver, glass, copper, ebony, and precious stones. In effect, the impression of mightiness from the statue impressed the ancients. This effect was Phidias' intent — to overawe with a vision of an omnipotent god — and Zeus' incredible amount of bling most certainly added to this sense of divine power.

The Statue of Zeus was not modeled on anybody

The statue of Zeus had accouterments that had symbolic and real value. According to Britannica, this included the goddess of Victory in one hand — wrought of gold and ivory — and a scepter with an eagle atop in the other. Per World History Encyclopedia, ancient traveler Pausanias noted that the statue also featured gold sandals and a garland with olive shoots. Ebony, glass, and gemstones were also used throughout the work. Elsewhere, the throne featured numerous depictions of characters from Greek mythology, all of whom were the children of Zeus. Even the footstool of the statue was ornately carved with scenes of Theseus fighting the Amazons.

In sculpture, it was common for artists to use human models — even of divine beings. But this was apparently not the case with Zeus or even Phidias' earlier sculptures. Centuries after the statue was completed, the Roman orator and politician Cicero was so impressed with Phidias that he felt his skill was beyond ordinary talent. "Greek Bronze Statuary" quotes him as stating: "Indeed that master, when he made the form of his Zeus or his Athena, was not contemplating anyone from whom he made an imitation; rather, some exceptional vision of beauty was fixed in his own mind, and, concentrating on it and contemplating it, he directed his art and his hand toward making an imitation of it."

The Statue of Zeus was widely imitated

The truth is that we do not really know exactly what Phidias' statue of Zeus looked like. As pointed out by Britannica, no accurate copies of the statue exist. We'll look at the destruction of the statue in a bit, but in the meantime, we do have a general idea of how the statue looked because of inaccurate copies. Even modern replicas created by 3D printers are all based on guesswork and historical deduction, as reported in Electronics 360.

Livius presents some of the ancient replicas that survived. All the replicas on the main page — be they sculpture or coin — have the god sitting on his throne with staff in one hand and Nike in the other. However, they are all different in the details, and none captures that actual experience of the statue. The University of Chicago quotes the geographer Pausanius who saw Zeus during the height of the Roman Empire: "I know that the height and breadth of the Olympic Zeus have been measured and recorded; but I shall not praise those who made the measurements, for even their records fall far short of the impression made by a sight of the image."

The Emperor Caligula attempted to move the statue, but failed

It was during the Roman Empire that the violation of the State of Zeus began thanks to the psychopathic emperor Caligula. This emperor was about as unhinged as they came — at least according to biased Roman historians. There is one possibly apocryphal rumor that the mad emperor tried to name his horse a senator. Indeed, Caligula was a megalomaniac and equated himself as a living god. In his eyes, he was the living incarnation of Zeus.

According to "Caligula: The Abuse of Power," the emperor planned to move the massive statue to the palatine in Rome for the cult of Jupiter (the Roman name for Zeus). However, the emperor was thwarted due to "practical difficulties" — perhaps the size of the statue overwhelmed Roman logistics teams. This explanation is more plausible than the fantastical myth posited by the Roman historian Suetonius, who wrote, "The statue of Jupiter at Olympia, which he [Caligula] had ordered to be taken to pieces and moved to Rome, suddenly uttered such a peal of laughter that the scaffoldings collapsed and the workmen took to their heels." Suetonius notes that this event was obviously an omen foretelling the insane emperor's death.

The Statue of Zeus was first violated by Emperor Constantine

After Caligula, the great statue was left alone for a time. However, it's gilding of gold and precious stones always provided a whiff of a temptation to those who needed quick money. This proved too much for Constantine, who was a far more effective ruler of the Roman state than Caligula.

As noted by "Seven Wonders of the Ancient World," Constantine — who reigned from 306 A.D. to 337 A.D. — was the first Christian emperor. It is perhaps for this reason that the emperor had little qualms of stripping the monumental work of its gold. "The Age of Constantine the Great" notes how the unashamed emperor cited the panegyric of Constantine to defend his actions: "The valuable portions were melted down, and the amorphous remainder was left to the pagans as a memorial of their reproach." Unfortunately for posterity and us today, many of the great artistic works of antiquity were lost in a similar manner.

The temple fell into decline with the rise of Christianity

The next major blow to the Statue of Zeus came during the reign of Theodosius, who outlawed polytheistic cults in 391 A.D. at the behest of the Church, as described by "Seven Wonders of the Ancient World." As a result, the Olympic games came to an end in 393 A.D. since they were at their heart a polytheistic cult festival. This development was a heavy blow to Olympia, and very quickly, the site started to get looted. Then, in 426 B.C., Theodosius II issued a decree against pagan temples, and the site of Phidias' workshop eventually became a church, per World History Encyclopedia.

A century later, in 522 A.D. and 551 A.D., earthquakes struck, destroying the site entirely. The ruins were eventually covered up by silt as the nearby Alpheus River changed its course over centuries. But the truth of the matter is that the statue was not destroyed in those earthquakes thanks to a eunuch.

The statue's final home was in Constantinople

While antiquities of the Mediterraneans' polytheistic heritage were being destroyed in the face of rising Christianity, a eunuch in the court of Theodosius II took a proprietary interest in the statue of Zeus at Olympia. According to the University of Chicago, Lausus was the imperial chamberlain by around 420 A.D. and was an avid collector of pagan antiquities. It was at some point in the early fifth century that Lausus had the statue removed from the temple and taken to his palace in Constantinople. There it was joined other remarkable statues of ancient Greek religion. However, Phidias' Zeus must have been the centerpiece. Unfortunately, a fire struck in 475 A.D., destroying Lausus' palace and the ancient statue of Zeus. Another theory offered by the World History Encyclopedia is that the statue was lost in an earthquake in either the fifth or sixth century. Either way, this monumental masterwork was lost for the ages.

Or was it? Much like other figures from Greek mythology, this image of Zeus was incorporated into the Christian tradition, as "Seven Wonders of the Ancient World" points out. Indeed, Zeus, sitting on his throne in Olympia, is the virtual image of the monotheistic god in his most omnipotent presence.

Zeus got to look at himself all day

If you were a god, who could blame you if you wanted to look at yourself all the time? This is just what the statue of Zeus did. "The Statue of Zeus at Olympia" describes how right in front of the statue, on the inside of the temple, was a reflecting pool. Reflecting pools aren't an unusual feature for monumental structures. One example is the reflecting pool in front of the Lincoln Memorial, for example. What was unusual was that this pool was filled with olive oil. This was, according to the ancient geographer Pausanias, because it was believed that the oil kept the air dryer in the humid and marshy climate of Olympia. Conversely, the statue of Athena at the Parthenon had a pool of water to create more humidity to prevent the ivory of that statue from cracking.

"Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World" points out that the oil pool probably had no impact on the temple's humidity, though; plus, humidity does not necessarily damage ivory such as what was used in the statue. Thus, it may have been meant for other purposes.

Nevertheless, this pool created a mirror-like image of the statue that magnified its aura, since the light would have bounced ashimmering up and into it, more reflective than water. It may very well be that feature imparted such majesty in it, which, more than its monumental size, made it a Wonder of the World.

The statue was liberally oiled

If the oil in the reflecting pool was not really a good tool for climate control, it could serve as a useful reservoir for maintenance purposes. In his ancient account, Pausanias explains that the descendants of Phidias were granted the privilege of being allowed to clean the statue of the grime and dust that would naturally and regularly collect on it. These people were called "Cleansers" which "Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World" notably translates to "shiners." They theorize that these shiners may have used the oil to treat the ivory — and especially the wooden — parts of the statue.

This was regular practice in the ancient world. In fact, some have suggested that the inner workings of the statue may have contained tubes in order to get the oil to the wooden parts. Another spin on this is that the reflecting pool may have actually been water, but the oil from the maintenance of Zeus spilled into it. This may have confused Pausanias, who claimed it to be an oil-filled reflecting pool.