The Truth About Ted Bundy's Time In Politics

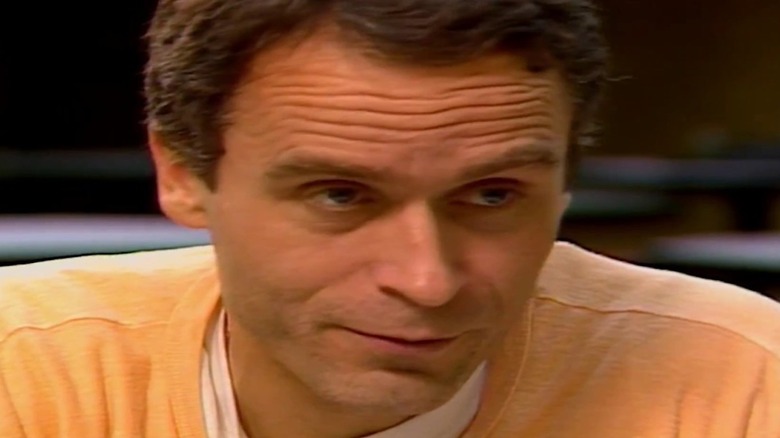

At first glance, Ted Bundy was the last guy most people would expect to be a serial killer. Not only was he a handsome man who knew how to make conversation with women and make them feel at ease; he was also highly intelligent, a college graduate who was attending law school at the time he committed some of the brutal murders he was accused of. But that's how it often is with serial killers — in many cases, they can come about as normal, law-abiding individuals and charm people into seeing them in such a positive light. That's one reason why, for better or worse, we've seen countless films and documentaries about Bundy, with the latest having just hit theaters in August and sparked social media conversation over the perceived romanticization of his crimes.

Before the world knew Ted Bundy as one of America's most notorious and prolific serial killers, there was a time when he showed great promise in conservative politics. Although Bundy had a troubled childhood and got in trouble with the law multiple times as a teenager, he had seemingly grown out of his rebellious phase and devoted his life to serving the Republican Party in any way he could. Here's the truth about Bundy's time in the world of politics.

Bundy worked for high-ranking Republicans such as Nelson Rockefeller

Stop us if you've heard this before, but the late '60s were a time of social and political upheaval. Much of America was up in arms over the Vietnam War, and once-clean-cut young men were growing their hair and beards out and joining the hippie movement. That wasn't the case with Ted Bundy, who maintained a short-haired, genteel appearance and openly aspired to live a normal, happy life with a wife, kids, and lots of material wealth. Bundyphile described him as a "perfect example of a modern Republican" and a natural in the political scene due to his charisma and forceful personality.

Showing his loyalty to conservative politics at a young age, Bundy, then only 21 years old, worked as a volunteer at the Seattle office of Nelson Rockefeller, the New York governor who was then seeking the Republican nomination for the 1968 presidential election. Not much else is known about Bundy's volunteer work, but in August of that year, he attended the Republican National Convention as a Rockefeller delegate.

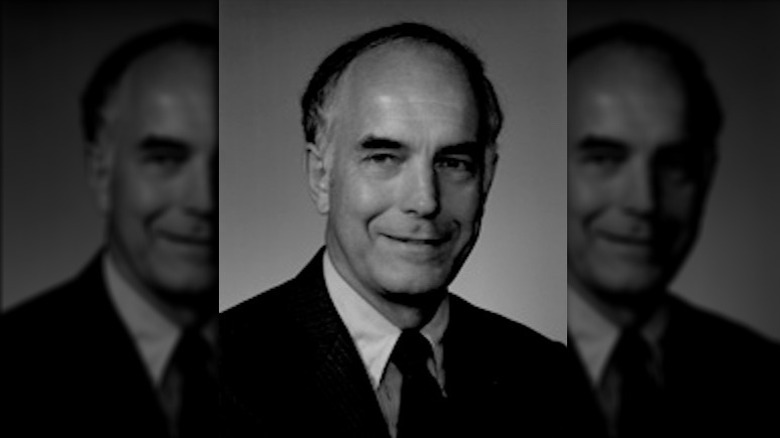

In the years that immediately followed, Bundy wasn't involved in anything political; instead, he returned to school and did quite well as a psychology major at the University of Washington. After graduating in 1972, he started working for Washington Gov. Daniel Evans' re-election campaign. This is where he first gained some nationwide notoriety, albeit not for the crimes he would eventually commit.

He essentially acted as a spy for Washington's Republican governor

During his time working for Evans (pictured above), Ted Bundy was already showing off his ability to blend in with other people and appear to be one of them. So uncanny was this ability that he was even featured in The New York Times. On page 23 of the newspaper's August 30, 1973, issue, the publication reported on a "Theodore Bundy" who posed as a college student during Evans' 1972 re-election campaign so that he could travel with the governor's Democratic opponent, Albert Rosellini, and gather information on his activities. Yes, this was the same man who would commit his first documented murder little more than four months after his name was mentioned on one of America's leading newspapers.

At the time of the report, Bundy was working as a special assistant to the state of Washington's Republican Party chairman, Ross Davis. According to the Times, the would-be serial killer started as an unpaid volunteer and was eventually given a small salary as he shadowed Rosellini, transcribed his public remarks, and questioned him about certain issues. Bundy would then forward the information to the Evans campaign, much like a pair of freelance writers who traveled with 1972 Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern and supplied whatever intel they gathered to President Richard Nixon, who was also running for re-election that year.

When asked to comment on his role with the Evans campaign, Bundy told the Times that he had no qualms about essentially spying for the governor. "It was just part of political campaigning," he added. "You have to know what your opposition is saying and doing."