This Is How Richard Nixon Nearly Messed Up The Charles Manson Trial

The events that unfolded in Southern California in August of 1969 shocked the world. On August 8, 1969, beautiful actress and mother-to-be Sharon Tate was savagely murdered in her Hollywood home, along with four others. Two nights later, on August 10, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca were murdered in the same fashion in their home in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles.

The crimes were eventually linked to a self-proclaimed prophet, Charles Manson. Manson had amassed a group of wayward youth, whom he lived with on the remnants of a dilapidated movie ranch at the base of the mountains east of LA. "The Family," as they were known to be called, consisted of more than 50 members. These folks had a reverence for Manson so strong that they carried out his orders to kill seven innocent people in a three-day span. Manson and several of his followers were also later linked to several other murders around the LA area.

Put on trial in 1970, Manson and three of his female followers were convicted in a nine-month-long trial (via Famous Trials). At the time, this trial was the most expensive conducted in American history. Ultimately, Manson and all three of his followers were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. Even though the U.S. Supreme Court later ruled capital punishment unconstitutional and vacated death sentences nationwide (a decision they later reversed), no parole board has ever allowed for the release of Manson or his followers convicted in the 1970 trials.

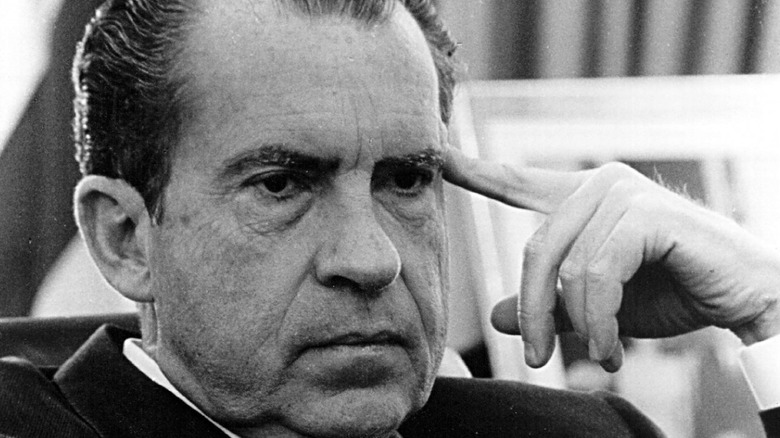

So how does former U.S. President Richard Nixon fit into the Manson trial, and how did he almost derail it?

A law-and-order President

Nixon ran his 1968 presidential campaign on the idea of law and order. The civil unrest that was occurring around the nation as a result of the United States' involvement in the Vietnam War had some Americans fearful. Adding to this was additional fear from escalating racial tensions, which thrust the backlash from centuries of racial inequities onto the television screens nightly. If Nixon knew how to do one thing, it was to capitalize on fear.

Nixon was only president for eight months when the Tate-LaBianca murders were reported out of California. A year later, the trial of the suspected murderers was underway. During the trial, Nixon was attending a private conference on crime control, as presented by the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (via The New York Times). This conference had more than 100 state and federal law enforcement officials and personnel in attendance. While on a break from the four-day set of meetings, Nixon briefly spoke to the Denver news media. When the topic of the Manson trial was broached, Nixon replied that Manson "was guilty, directly or indirectly, of eight murders without reason."

Though Nixon later retracted his statement, it nevertheless could have created a mistrial situation for prosecutors in Los Angeles.

Innocent until proven guilty in a court of law

Upon hearing the President's statement that Manson was guilty, Manson's attorneys wasted no time rushing to their client's defense. They called for a mistrial, stating that the remarks from a sitting United States president would be damaging to the defense's case (via Mental Floss). In fact, the front page of the Los Angeles Times led with the headline "Manson Guilty, Nixon Declares." The front page of this paper was used as a prop by Manson himself when the request for a mistrial was presented to the judge in the case (via A&E).

Nixon quickly issued a retraction, but not before blaming the media's coverage of the murders and the trial, citing sensationalism. Nixon felt the media was making Manson a star, when he was just an "alleged" cold-blooded killer. Nixon stated he had a "clarification" on his earlier statement regarding Manson, and went on the record saying he meant to use the word "alleged" in his earlier comments to the Denver media (via The New York Times).

The President's comments about the Manson trial didn't go unnoticed by others in the legal community. An American Civil Liberties Union representative decried that it is "an extremely unfortunate insensitivity to the judicial process for any lawyer — and the President is one—to assume a person is guilty before his trial is over."

The defense's request is denied

The judge in Manson's trial rejected the request from his attorneys to declare a mistrial and his reasoning was that the headline had no influence on the jury, who had already been selected and had been instructed to not read media accounts of the trial. Each juror swore under oath that they were not swayed by the headline being shown in the courtroom by Manson, and would only consider evidence that was entered officially into the court (via A&E).

If the judge had granted the defense's request for a mistrial, does this mean that Manson would have been free to go? Not likely. A mistrial isn't like being exonerated of a crime. Rather, it just shows that something interfered with the legal process, resulting in the trial not being fair and just for either side. Prosecutors routinely refile charges after a mistrial, if they still believe they have sufficient enough evidence to prove a defendant is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

With Manson's case, in particular, there was a mountain of evidence that he was guilty. While a new trial would have proven costly, it's highly probable that the prosecution wouldn't have let Manson off the hook.