Here's What It's Like To Be An Amish Teen During Rumspringa

Unless you're Amish yourself, chances are good that you've got some of their beliefs all wrong. According to Elizabethtown College's Amish Studies, there are quite a few different Amish groups out there with different rules on things like dress, transportation, and use of modern technology. And while agriculture is still a major part of the Amish lifestyle, it's not the only way to make a living and still be in good standing with one's community. But, while there are plenty of misconceptions, there's one practice that could very well be the most misunderstood of all: rumspringa.

Broadly speaking, rumspringa is a practice where Amish teens socialize amongst themselves and, for many, experience something of the outside world. Depending on the Amish group that raised a teen, the youths experience a wide range of permissions. Sometimes, that includes the chance to experience wild parties; other times, it's more along the lines of games of UNO (via "An Amish Paradox"). The idea is that youth will be able to make an informed decision about whether or not to join the church as adults. The Amish are anabaptists, meaning they practice adult baptism (via Amish Studies).

Some of the more notorious takes on the practice, like 2002's "Devil's Playground," make it seem like rumspringa is a free for all. In the film, some teens admit to actions that seem shocking for conservative Amish, like drinking alcohol. But is that true for all? Here's what it's really like to be an Amish teen during rumspringa.

Rumspringa is all about experiencing the outside world

According to "Rumspringa: To Be Or Not to Be Amish," the term for this period of time in an Amish teen's life can be translated from Pennsylvania Dutch (spoken by many Amish communities) as "running around." Essentially, it's a chance for young people in Amish groups (of which there are quite a few with varying beliefs and levels of strictness) to spend time outside of their everyday life. For many, that also means they will experience the world beyond their communities to some extent. In doing so, they're supposed to be empowered to make a decision about whether or not to join the church as adults. If they choose to be baptized into the church, that will mean adhering more strictly to unspoken community rules known as the ordnung (via How Stuff Works).

The Amish Studies program at Elizabethtown College notes that this dip into the "outside" world can take quite a few different forms. Some teens might dress in worldly clothes, drive cars, and watch television, for instance. Some might go genuinely "wild" at parties and even visit bars to consume alcohol (drinking is a big no-no for New Order Amish, according to Amish America, though other communities are okay with the occasional drink). Others could also take a pretty sedate route, with wholesome hiking meetups and get-togethers where everyone signs hymns in a group setting, taking the "outside" part perhaps not as seriously as some other young Amish people do.

Rumspringa is part of a complicated system of obligation and free choice

Part of the point of rumspringa is to allow Amish youth a chance to experience a taste of the outside world. With that knowledge, they can then theoretically make an informed decision as to whether or not they want to join the church and become a full-fledged member of their community. How Stuff Works notes that, generally speaking, someone can't make this decision until they're at least 16 years old. That's in line with Amish anabaptist beliefs that only recognize an adult's conscious, informed decision to join the church (via Amish Studies).

However, this decision isn't always cut and dry. If a teen declines to join the church, they can possibly damage ties with not only their family, but also the only community they've ever really known. They won't necessarily be shunned, in which all ties are broken between a community and someone who's already joined the church and would therefore be breaking an oath, per How Stuff Works. Teens who step away after this rumspringa period are in more of a gray area, given that they haven't taken any oaths.

Still, the tension between the free choice of rumspringa and the obligations, spoken or otherwise, that are imposed by their church and family, can be considerable. Sure, it's technically a free choice, but neither is it fair to pretend that the choice between joining the church and leaving your only known community behind takes place without consequences.

Rumspringa isn't exactly about going wild

Though many Amish communities ignore relatively minor infractions when it comes to kids going on their rumspringa, neither do they necessarily give teens a free pass to act wild. Of course, the exact nature of rumspringa and just how much oversight is levied by the adults differs from community to community. Time and place also have a pretty significant effect. But, generally speaking, it's not the goal of parents or other elders that the teens in their care stray too incredibly far from Amish values.

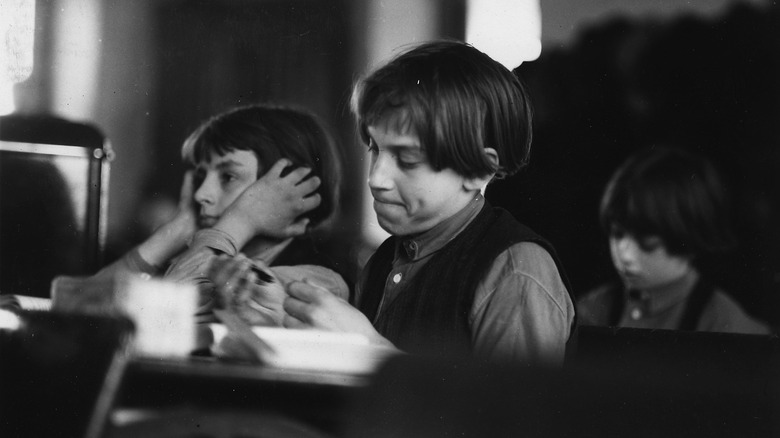

Traditionally, rumspringa has been pretty tame, says Amish Studies, with relatively inoffensive activities for rumspringa teens like ice skating, picnics, and rounds of volleyball. Teens might also gather for "singings," where groups of youth gather to sing hymns in someone's home, followed by food and socializing. Ultimately, the exact tenor of a teen's rumspringa depends largely on who they hang out with. Not unlike the youth of practically any other community throughout the world, the influence of someone's peers can have a dramatic effect on a single teen's path through this period.

According to NPR, size matters, too. Areas where there are quite a few Amish people give teens a certain level of anonymity and can lead to more widespread acceptance of rumspringa wildness. But, if you were an Amish teen in a smaller group, you can't hide nearly as well and may be more restricted even in what's supposed to be a time of exploration.

There's a lot of variety in how it happens

Rumspringa can differ dramatically from individual to individual. As "An Amish Paradox" points out, even single communities can contain all varieties of takes on rumspringa. Amish people in Holmes County, Ohio, for instance, run the gamut from complete denial of rumspringa to regularly allowing their teens to do such worldly things as attend parties.

In settings where adherence to the community takes precedence, rumspringa can get about as wild as playing a card game once in a while. These, not coincidentally, happen to be in places where Amish settlements are smaller and perhaps more isolated. Larger groups may be more permissive, while smaller ones naturally have quite a bit more oversight.

And, of course, you can't dismiss the influence of individual teens, either. Just like adults are individuals with different ideas about how to live life with the overarching authority of the church and its behavioral rules (known as "ordnung"), so too do teens form their own opinions. And, while some are clearly interested in pushing boundaries, not all are willing to move too far away from the oftentimes enclosed community that raised them. American Experience interviewed Amish teens who outlined some of their local teen groups, like the "Low Clinton" ones who, in the words of one youth, "would basically be like their parents." Another noted that "you're giving up a lot" when you decide to break away from your Amish family life, too.

Rumspringa has a marked gender divide

Amish society in general has a pretty marked set of gender roles. According to Amish Studies, women and girls are traditionally expected to take on domestic tasks within the home and raise the family's children. They're also meant to stay subordinate to the men in their lives, like their fathers or husbands. Men, meanwhile, are to support their family financially and lead them spiritually as well. There are individual variations on this theme, of course, but it's a pretty safe bet that most Amish families and larger groups will fall into this broad gender categorization.

Those gender roles also tend to trickle down even into the relatively freewheeling word of rumspringa. "An Amish Paradox" reports that boys tend to get more freedom than girls when it comes to what's allowed during this period, sometimes even receiving gifts or allowances that offer them more freedom. These could include a horse-drawn buggy or even access to a car that allows them to go even farther away from home. They might also be spotted fairly frequently at parties and in decidedly non-Amish clothing.

Girls, meanwhile, are more likely to face restrictions. According to a student research paper shared by the ex-Amish band, The Amish Outlaws, while boys might live on their own for a while, that's pretty rare for girls. Young women are also more likely to stick to traditional clothing and are less often seen driving, at least compared to their male rumspringa counterparts.

This time is an opportunity to forge social connections

While rumspringa is oftentimes described as a way for Amish teens to decide whether or not they want to become an even deeper part of Amish life, that's not all it does. According to PBS' American Experience feature on the Amish, this is also a period of time where youth can establish important social connections.

All those gatherings and parties, whether they take the form of wholesome hymn-singing get-togethers or somewhat less decent trips to the bar, forge friendships amongst youth. And, given that quite a few of them are likely to return to the Amish fold — some 90 percent of them, according to American Experience — those relationships can serve them well in their lives as adults. In a relatively communal setting where you might rely on your neighbors for help or provide that support yourself, those social connections forged in the relatively wild days of rumspringa can pay dividends.

Rumspringa is also a pretty good time to find a potential spouse. People interviewed for "Rumspringa: To Be Or Not to Be Amish" often noted that they decided to return to the Amish way of life in part because they'd decided to get married. And, if someone's future partner wants to join the church and submit to the ordnung, then it naturally follows that they would, too. Having a potential wife or husband who's dedicated to being Amish is a powerful factor in one's decision to discard their rumspringa ways and become a fully-fledged adult.

Heaven and hell are still major concerns during rumspringa

For Amish youth, it's difficult to escape the highly religious upbringing that is central to their lives. And, for many teens who take steps outside of their community, that means thinking about the prospects of both heaven and hell.

That's not just a concern for the teens. "An Amish Paradox" reports that adults in the community might fret about the moral weight of what goes on during rumspringa. If a particularly rebellious youth were to die while drinking or driving a car, for instance, what would happen to their souls? Sure, they haven't necessarily joined the church, but that doesn't mean their eternal fate doesn't still hang in the balance. Some fear this prospect of getting "caught out" more than others, with one woman recalling that she worried about suddenly dying before she'd had a chance to throw away her record player and subsequently going straight to hell.

This sort of fear can create some truly difficult moral dilemmas for Amish youth. "Rumspringa: To Be Or Not to Be Amish" notes that, while teens from the outside world might double down on their participation in youth culture, anxious Amish kids on rumspringa could well do the opposite. The shock of their own inevitable death and the prospect of being condemned to eternal torment if they don't behave so terrifies or motivates them that the decision is pretty clear. Teens therefore readily return to the Amish way of life and the comfort of religious certainty that they've always known.

Many choose to return after rumspringa

According to American Experience, the vast majority of Amish youth return from their rumspringa and decide to become full members of the church.

The desire to return to the fold after the rumspringa period is influenced by many different factors. For one, as "An Amish Paradox" notes, few Amish youth actually get a taste of the outside world. Instead of socializing with "English" people (a common term for non-Amish outsiders, per Amish America), teens are far more likely to join up with groups of other youth from the community. Given that they've probably already met in places like church or in work settings, their forays into settings beyond their community are still heavily influenced by their uniquely Amish upbringing.

Then, there's the matter of their community's survival, says NPR. It's also a matter of numbers — if enough teens decide to stay away and continue their lives in the outside world, then their old community faces an existential threat. Without enough young Amish people marrying Amish spouses, they won't produce future generations of Amish and so their ways could potentially die out. What's more, "Rumspringa: To Be Or Not to Be Amish" reports that many youth are already primed to follow their parents and the well-established and relatively stable world in which they have grown up. The fast-paced and constantly changing landscape of the outside may be intimidating or even just undesirable to them, and so they largely leave it behind after rumspringa.

Teens who choose to leave face a complicated road

While it's true that a great many Amish youth move out of their rumspringa time and follow along with the already established ways of their family and larger community, that doesn't apply to everyone. The inherent risk of rumspringa and the freedom of choice that's part of it means there's the possibility that a teen might decide to leave it all behind. Of course, that's no easy decision.

Technically speaking, youth who break away during their rumspringa and before they join the church cannot be shunned, according to How Stuff Works. They aren't necessarily subject to the harsh conditions afforded to shunned church members, who are seen as having broken a vow and are therefore excommunicated from the church and generally denied by members of their former Amish group. Those who leave during rumspringa, however, haven't taken any such vow.

But that doesn't mean they have a smooth path ahead of them. According to ABC News, some teens reported feeling deeply confused by the unspoken rules and regulations of the outside world. Others had limited contact with their families, sometimes because their parents feared the sort of influence a breakaway son or daughter might have on their siblings. Over time, members of the small group interviewed by ABC returned to the community and fell into line, while others established lives for themselves outside of the bounds of Amish life and what they believe to be a restrictive set of rules.

Rumspringa has been sensationalized by the media

Many people, perhaps egged on by Lucy Walker's 2002 documentary film "Devil's Playground," assume that rumspringa is universally a time where Amish youth discard all old social rules. While that may be true for some, it's not right to apply it to all. Amish people themselves may not be keen to talk about the practice frankly for this very reason. As one student researcher from Georgia State University said, "I can attest to being on the receiving end of a heavy sigh a few times after mentioning my research intentions."

"An Amish Paradox" claims that Walker's documentary focused on the wildest teens who were willing to go so far as to drink, smoke, and even have intimate relations with each other. Reality TV hasn't helped clear things up, either, says the journal Western Folklore. The tenuous "reality" of shows like "Amish in the City" seems to have contributed especially to the confusion. In this 2004 series from the now-defunct UPN network, a group of Amish and non-Amish young adults live together in Los Angeles.

Of course, reality television is highly constructed, and "Amish in the City" seems to have been no exception, even as it claimed to show young people in the midst of rumspringa. It also oftentimes seemed to set its participants apart, with some of the harshest critics claiming that the series was little more than a sideshow presenting a cartoonish and inaccurate version of both rumspringa and wider Amish culture.