The Untold Truth Of Harry Caray

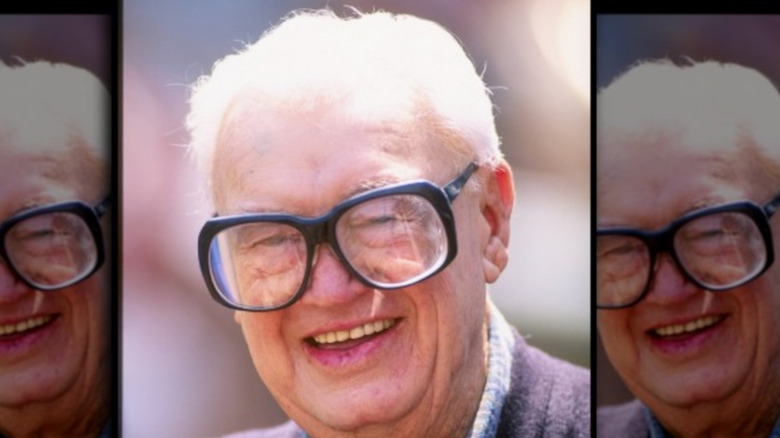

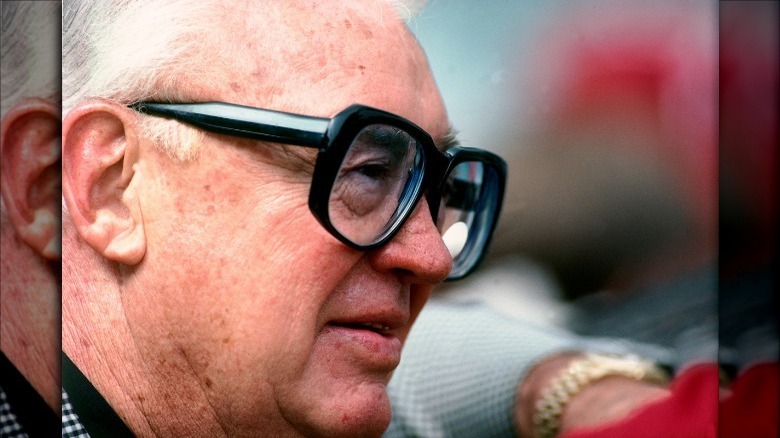

Harry Caray was one of a small number of people who transcended their cultural niche. A legendary baseball broadcaster, Caray's larger-than-life personality crossed over into mainstream pop culture. His signature look that included oversized glasses, his loopy, easily distracted broadcasting style, and his catchphrase "Holy cow!" were so familiar, even to folks who paid no attention to baseball, that Will Ferrell parodied Caray on "Saturday Night Live" on a regular basis.

When someone like Caray becomes so easily identified with their tics and public persona, the truth of their lives is often lost. Although Caray did have a few moments of controversy in his long career, that public persona was largely inoffensive, making it easy to assume that he was the same way in private as he was in public. But it's key to remember that in many ways he was an entertainer. Behind the glasses, the amiably confused play-by-play, and leading the crowd in singing "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" during the seventh inning stretch with what can only be described as more enthusiasm than singing ability, Caray was more complex and layered than most people assumed.

Over the course of a colorful life he carved out a place in the American Sportscasters Association Hall of Fame, the Radio Hall of Fame, and the hearts of baseball fans everywhere. Here is the untold truth of Harry Caray.

Harry Caray had a turbulent youth

Harry Caray spent his career in the broadcast booth building a public image as a funny, laid-back baseball superfan. His enthusiasm during the games he called was palpable — simply put, he made watching baseball games more fun.

For a long time, Caray's life prior to baseball was purposefully obscure. As "The Legendary Harry Caray" explains, for decades no one knew the details of Caray's birth or childhood, and Caray himself appeared to be making up his own life story as he went. Caray usually claimed to be part Romanian and part Italian when in fact he was Albanian. He also often claimed to be younger than he actually was — when he passed away in 1998, different news outlets gave out different ages.

Caray was born Harry Christopher Carabina in St. Louis in 1914. His family wasn't well-off, and his father left to serve in the army during World War I and never returned. According to Deadspin, his mother passed away when he was still a child, and he went to live with his aunt, Doxie Argint. When Argint's husband moved out, she struggled to raise Harry and his cousins. "Take Me Out to the Ball Game: The Story of the Sensational Baseball Song" reports that Carabina changed his name to Caray when he was told by radio managers that he sounded "too foreign."

He wanted to play baseball

Harry Caray is so closely associated with baseball that it isn't too much of a surprise that he was a huge fan of the sport since childhood. In fact, his original life plan involved playing baseball.

According to the Society for American Baseball Research, Caray played second base for his high school team, and he was good enough to be offered a scholarship to the University of Alabama to play for the college team. But "The Legendary Harry Caray" reports that Caray had to turn down the opportunity. Even with his tuition covered, Caray couldn't afford the other expenses of room and board, books, and travel.

Britannica reports that Caray sold gym equipment for a while to make ends meet. He remained an ardent fan of baseball, though, attending many games in person but also listening to Cardinals' game on the radio. He wasn't a fan of the dull, restrained style of broadcasters at the time, so he took it upon himself to write a letter to the general manager at KMOX in 1940, asking for a job doing baseball play-by-play. That got him in — the manager thought he had a good voice but needed experience, so he got Caray a job calling minor league games. Caray's career was almost interrupted when he was called in for the draft in 1943, but he didn't pass his army physical due to poor eyesight.

His legendary cluelessness was an act

Part of Harry Caray's appeal was his loose, fun style. As "The Legendary Harry Caray" explains, he was often described as a "homer," a broadcaster who was an unabashed fan of the home team. In fact, Bleacher Report ranked Caray as the number two homer broadcaster in baseball history.

But that was part of Caray's style and appeal, as were his other foibles behind the microphone. Caray frequently mispronounced player's names, and often got details incorrect when discussing plays or other matters on the air. But, as USA Today reports, according to Caray's one-time broadcasting partner Steve Stone, it was all an act. Stone said that he would spell out names phonetically for Caray before games, but Caray would still mispronounce them on purpose.

USA Today also reports that Caray kept buying larger and larger glasses over the years, ultimately ending up with the comically large pair he's remembered for, but these were part of his act. And although there's little doubt that Caray liked his beer, when doctors ordered him to stop drinking in his later years he would drink non-alcoholic beer and pretended it was the real stuff. Caray knew that people tuned in for the persona, and he was careful to keep it up throughout his entire career.

Harry Caray drank a lot

It's true that Harry Caray's love for beer was part of his manufactured image, but it's also true that the man sincerely loved drinking beer, and he drank a lot of beer — as well as martinis made with Bombay Sapphire gin. How do we know? Because Caray kept booze diaries.

USA Today reports that for a while Caray thought he might be able to claim his bar tabs as expenses on his taxes, since he visited bars while traveling to cover away games. So he kept careful records of the bars he visited. In 1971 alone he stopped at 1,362 different bars. In 1972, he slowed down and only visited 1,242 taverns.

How did Caray put up such Hall of Fame drinking numbers? Dedication. ABS News reports that he set a personal record in 1972 by drinking for 288 straight days, and according to Thrillist he would often visit five or six different bars in an evening, and drank 354 days out of 365 that year. In other words, Caray approached drinking with the dedication of an Olympic athlete. Caray once claimed he'd consumed 300,000 drinks over the course of his lifetime, and Thrillist did the math to conclude that the man drank more than 110,000 beers.

He was a divisive broadcaster

Today, Harry Caray is a legend. He's a member of both the Radio Hall of Fame and the American Sportscasters Hall of Fame, not to mention the recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award from the National Baseball Hall of Fame. That's a lot of Halls of Fame, and Caray's iconic visage is still instantly recognizable, especially in Chicago and St. Louis.

People think of Caray as the slightly incoherent, enthusiastically biased broadcaster who led fans in (an apparently inebriated) rendition of "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" every seventh inning stretch. What many don't realize is how revolutionary he was in the broadcast booth. As noted by the Society for American Baseball Research, when Caray debuted his own sports news radio show in the 1940s, he was one of the first to inject his opinions and commentary into his broadcast, and not everyone loved it.

His personal style of play-by-play was also controversial. Deadspin reports that in 1968, Sports Illustrated wrote an article noting how out-of-step Caray's loud, boisterous approach was with other baseball broadcasters, who favored a more objective, unobtrusive style. Caray gave the disdain right back, though, complaining about "This blasé era of broadcasting!" Additionally, many of the athletes on the field thought Caray was too personal and opinionated because he never hesitated to ridicule them for bad plays, just like any other fan.

He was once held up at gunpoint

As anyone who has ever gone out for a night of drinking knows, alcohol and late nights often lead to complications. Harry Caray, who Thrillist explains would often visit five or six bars in a single evening, knew this better than anyone after he was held up at gunpoint one evening.

Steve Stone, former Cy Young Award-winning pitcher and longtime broadcasting partner with Caray, told NBC Sports that one evening Caray left a watering hole late at night to find that his car wouldn't start. He called for a tow, then settled down to wait. Suddenly, a car pulled up next to him and two men emerged, one holding a gun. Caray immediately offered his valuables, hoping to get out of the situation unharmed.

According to Audacy, however, there was a happy ending. The man with the gun suddenly put it away and became emotional. He told Caray he was a huge baseball fan, and a huge Harry Caray fan. He began telling Caray he'd grown up listening to him on the radio, and how important he'd been to him over the years. He offered to give Caray a lift to a gas station and left with a warning that Caray shouldn't hang out in bad neighborhoods at that time of night.

He was a broadcasting pioneer

Not everyone loved Harry Caray's homer-style of sports broadcasting, but one thing is beyond argument: Caray changed how sports broadcasting was done. When he started doing play-by-play for baseball games in the 1940s, radio stations almost never sent broadcasters on the road to cover away games. The result was a pretty dry broadcast in which commentators simply announced what was happening.

According to "The Legendary Harry Caray," Caray decided to inject more showmanship and drama into those away games. He not only brought his usual enthusiasm and excitement, he worked to recreate the game's atmosphere. He used sound effects — crowd noise and even vendors shouting out their wares — to make it sound like he was really there. According to Chicago News WTTW, he was so successful that people thought he had traveled to be with the team. The popularity of these broadcasts was what convinced stations to starting sending broadcasters on the road for real.

Behind all the showmanship and blatant, charming home-team bias, Caray was also an extremely good play-by-play professional. NBC Sports explains that Caray was considered one of the best technical announcers in the game before he became a wildly popular goofball later in his career.

A lot of Harry Caray's legend was motivated by money

Harry Caray loved baseball and loved being a broadcaster, but he was as human as the rest of us, and he also loved money. In fact, many of the most famous pieces of his broadcast persona were blatantly motivated by cash.

As reported by the Chicago Tribune, it was no secret that when Caray first made a national name for himself as the broadcaster and play-by-play man for the St. Louis Cardinals, he was essentially a salesman for Anheuser-Busch, promoting their beer. When the company wanted to launch a new beer, Busch, they sent Caray out to the stadium to talk it up, and it became the first new beer to successfully launch in decades.

Even Caray's famous singing during the seventh inning stretch at home games was motivated, at least in part, by money. According to the Society for American Baseball Research, when Caray started working for the White Sox in 1971, the team couldn't afford his usual salary. Instead, it offered him a bonus structure based on attendance: $10,000 for every 100,000 spectators over 600,000 in the year. Caray's drawing power worked to his advantage, and the team had attendance of about 800,000. According to ABC News, Caray leaned into the entertainment side of his work in order to maximize attendance as a result, leading to many of his signature bits, like his wild singing of "Take Me Out to the Ballgame."

He was hit by a car and almost died

In 1968, Harry Caray was working in the broadcast booth for the St. Louis Cardinals, and was very popular with the fans. As Deadspin notes, sportswriter Skip Bayless called Caray "the best baseball broadcaster I ever heard" during his work for the Cardinals in the 1960s.

So it was incredibly shocking when Caray was hospitalized after being hit by a car on November 4, 1968. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Caray was hit while crossing the street near his hotel. The driver claimed that rain prevented him from stopping in time when Caray stepped out in front of him. Caray suffered two broken legs, a dislocated shoulder, and numerous other injuries.

For fans of Caray, the question of whether he would be recovered enough to get back into the broadcast booth for the 1969 season opener was a huge concern. According to USA Today, Caray was ever the showman, giving out very little information in order to keep fans in suspense. Then, on opening day, he really leaned into the performative side of his work. After the team was introduced, the announcer shouted Caray's name. He emerged from the Cardinals' dugout on crutches. Halfway to the microphone on the field, he tossed one crutch aside to cheers. Then he tossed the other, and the crowd went wild. Asked by pitcher Bob Gibson about the crutches, Caray said "It's show business, Gibby."

The Cardinals fired him

Harry Caray was such a beloved figure by the time of his passing, it's difficult to believe he was ever fired from a job. But he certainly was. As reported by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Caray was fired from his broadcasting job on October 9, 1969. Well, "fired" might be too strong — Caray's contract was simply not renewed for the 1970 season. The move shocked fans.

The official statement from the team, which was owned by beer giant Anheuser-Busch, was that market research had prompted the move. It said "We felt Caray would not fit into our 1970 program." Caray was angry, saying "you'd think that after 25 years, they would at least call me in and talk to me face to face about this." He also dismissed the reasons given by the company, noting that "I've heard a lot of rumors involving personal things."

According to the Society of American Baseball Research, those "personal things" involved a rumor that Caray had engaged in an affair with August Busch III (pictured)'s wife, Susan. Busch owned Anheuser-Busch and the Cardinals, and was Caray's boss in every way. Caray never denied the rumors, cheekily stating that they were good for his ego. As a testament to Caray's popularity, fans staged protests and circulated petitions outside Busch Stadium.

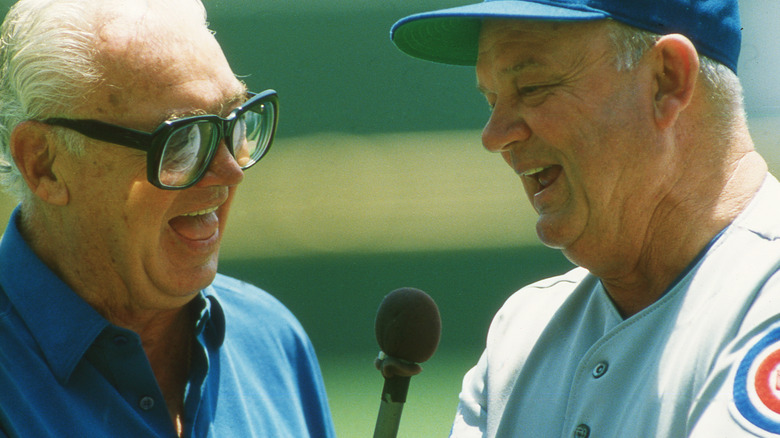

His broadcast partner hated him

Harry Caray was a very charming, lovable guy who had a lot of fans. But he wasn't universally loved. He occasionally made enemies on the field when he criticized players, but one of his greatest enemies was a co-worker: Milo Hamilton (pictured).

As reported by the Los Angeles Times, their relationship got off to a bad start. Hamilton was working for the Chicago Cubs and was poised to become their lead broadcaster. But then the Tribune Company bought the team and brought the popular Carey over from the White Sox. Hamilton and Caray spent one season working uncomfortably and unhappily together, and then Hamilton moved into the radio side. Three years later, he jumped to the Houston Astros.

The enmity between the two men became legendary. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reports that Hamilton blamed career setbacks on Caray's manipulations, and Caray refused to even mention Hamilton in his autobiography. According to the Chicago Tribune, the two men never spoke again and avoided each other at all costs. Cary's dislike of Hamilton led to a rare moment of public meanness from the legendary broadcaster. According to the Chicago Tribune, when Hamilton was in the hospital for leukemia treatment, Caray said live on the air "I never missed any games. I don't understand how a guy can take time off during the season."

Harry Caray used his power

Harry Caray's public image was of an amiable, slightly confused baseball superfan, but most people don't know that behind the scenes he was something of a shark.

For one thing, Caray often used the power of his position to pressure players into interviews or other interactions. According to "The Legendary Harry Caray," when Cardinals' third baseman Ken Boyer refused an interview with Caray, the broadcaster began to ride Boyer incessantly, criticizing everything he did and comparing him unfavorably to star player Stan Musial at every opportunity.

According to the Chicago Tribune, Caray's partner in the Cubs broadcast booth, Milo Hamilton, openly accused him of getting him fired from at least one job simply because the men didn't like each other. Chron reports that Hamilton was pretty blunt about Caray, saying that he treated people poorly all the time and "was a miserable human being."

And Deadspin reports that many people came to believe that Caray was actually the "power behind the Cardinals throne," using his influence with owner August Busch III to get players traded and other members of the organization hired or fired. That makes Caray's own firing by Busch pretty ironic.