Why The Gut Is Called The 'Second Brain'

So you know the phrase "gut feeling"? We use it in English to mean instinct, or driving force, a certain difficult-to-describe sense that indicates what choices we ought to make. The implication is, that despite all of humanity's intellect and "higher learning" — astrophysics, the scientific method, creative expression through various media, take your pick — there's something deeper that understands us better than ourselves. And it's a wise idea to listen to it, lest we lose touch with some important part of our inner world and its unconscious, autonomic drivers. "Gut feelings" try to protect us from bad decisions.

As it turns out, researchers are just starting to realize that "gut feelings" may be far more literal than previously realized. The gut, which includes the entire, highly complex digestive tract, from throat to anus, is composed of its own, separate network of 100 million neurons, the same cells that make up your brain. And this "enteric nervous system," as Science Direct says, operates in the same way as the brain does: neural transmitters, synapses, receptor sites, electric signals, and so on. The enteric nervous system connects to the central nervous system — brain, spine and its nerves — by a two-way communication system along the vagus nerve, but can also operate 100% independently. As the American Psychological Association quotes comedian Stephen Colbert, the gut is "the pope of your torso." And as researchers are discovering, "the pope" guides human action far more than previously realized.

The 'gut feeling' of trillions of bacteria

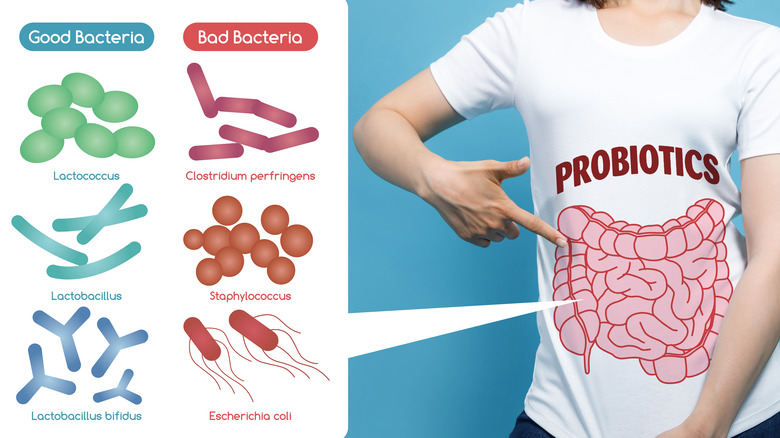

Gastroenterologist Premysl Bercik, MD at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada says, "We're just scraping the surface. Definitely the animal data suggest that bacteria can have profound effects on behavior and brain biochemistry, probably through multiple pathways." The bacteria he's talking about? The single-celled organisms that live within us and our digestive tract and outnumber our own cells 10 to 1, per the American Psychological Association. For the record, that's about 100 trillion microbes.

It should make sense that the gut is "intelligent," in a way. Eyes, ears, nose, mouth, tongue — our "five senses" — evolved to seek food and mates, while avoiding danger. If your gut has an excess of harmful bacteria in it — maybe the tofu in your pad Thai wasn't properly refrigerated — then it tells the brain that you ought to feel more anxious, reserved, and so on. Your choices about what to eat, where to go, how to speak, and what to do are steered in a certain direction.

Think of yourself as a worm, if you will (no disrespect intended). A worm is basically a mobile gut. It's a tube — intake on one side, and exhaust on the other. People are just the same, except we've got some wobbly limbs and feet with arches, and do things like laundry on Sunday and wish we'd remembered to buy batteries at the store. Digestion came before higher brain functions, otherwise worms would be our masters.

The ENS is key to mental health

Using some truly cool images to illustrate, both Science Focus and We Forum go into further detail about the biological tether between the gut and the brain, even suggesting that the gut is our true, "first brain." The enteric nervous system (ENS) of the gut, which operates totally on its own, plays an enormous role not just in scuttling the food and drink of ingestion down toward its eventual exit into a toilet, but in everyday mental health.

Serotonin, a key neural transmitter at the heart of clinical depression, lives primarily in the gut — 95% of it, in fact. Researchers are now examining the connection between its prevalence and electrical signals sent to and from the brain. Links are also appearing between the vitality of the gut and everything from obesity and rheumatoid arthritis to Parkinson's disease and other neurodegenerative illnesses. Blood flow, gland secretions, hormone diffusion, the regulation of the immune system: The gut and its standalone biome of microbes is central to them all.

Until the present, scientists weren't actually sure how the gut orchestrates its supremely intricate, nutrient-siphoning system. Now we know that the ENS is "far more complex than expected and considerably different from the mechanisms that underlie the propulsion of fluid along other muscle organs that have evolved without an intrinsic nervous system," reports We Forum. Understanding it is "a major focus for 21st-century medicine," says Science Focus.

Looks like our gut feelings are spot on, after all. Time to listen.