The Untold Truth Of Hearst Castle

If you spend any time at all in the realm of late 19th and 20th century history, then you're eventually going to run across the figure of William Randolph Hearst. In fact, unless you restrict yourself to a very narrow field of view, it's all but impossible to escape him. Hearst was a newspaper publisher who also dabbled in Hollywood, American politics, and more. And, as Britannica notes, his oftentimes ruthless and sometimes sensationalist tactics sold papers, but dramatically changed the landscape of news and the media in the early 20th century.

And it all made Hearst a very, very rich man. There's a lot that could be said about Hearst's life or how he spent his money, but one of the grandest and most obvious signs of his money is the estate that's now known as Hearst Castle. Located in San Simeon, California, this collection of structures is perhaps one of the most classic evocations of Hearst and his sensibilities. From the opulent central residence, to the extensive art collection, to the private zoo that once took up a surprising amount of space there, it's all enough to make you feel a little dizzy. And that's all before we even get into the history of this place. This is the untold truth of Hearst Castle.

Hearst Castle is stupendously large and expensive

One of the most obvious things you can say about Hearst Castle is that it's big. As in, really, really big. And yet, standing in front of it for the first time, you're still likely to be astonished by the sheer scale and lavish spectacle of this 20th century mansion. It really is that huge.

With 115 rooms, the main residence of Hearst Castle, sometimes referred to as La Casa Grande, covers over 68,000 square feet, per Britannica. It originally sat on a 40,000-acre parcel purchased by William Randolph Hearst's father, George Hearst. In the beginning, that land was effectively a family campground that remained relatively undeveloped for years, known as Camp Hill. It was only when William Randolph Hearst contracted with architect Julia Morgan "to build a little something" on what was then a 127-acre plot that things started to get going. Planning began in 1919, with construction continuing on into the end of the 1940s.

Though it's pretty obvious that the decades-long construction of Hearst Castle cost a pretty penny, the exact number is surprisingly hard to pin down, perhaps because of the many different projects that took place there over the years until finally stopping in 1947. Curbed reckons that it would have cost about $500 million in today's money, while Smithsonian bumps it up even higher with an estimate of $700 million.

It was designed by a woman

Rather surprisingly for the era, Hearst Castle was designed by a pioneering female architect, Julia Morgan. Yet, regardless of whether or not William Randolph Hearst himself was consciously trying to be a progressive man when it came to selecting an architect for his project, it's clear that he wanted someone really good. And, by the time Morgan came onto Hearst's radar, she had already established that she was far more qualified than many other architects, regardless of gender.

It seems pretty clear that Morgan knew what she wanted from an early age. According to the New York Times, she began her studies at the University of California, Berkeley in the civil engineering department. A mentor encouraged her to study at what was then the best architecture school in the world, Paris' Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Morgan became the first licensed female architect in California and opened an office in San Francisco in 1904, reports Hearst Castle. She began work on Hearst Castle in 1919 after already designing buildings for the University of California and a number of high-cost residential projects, including Hearst's mother Phoebe's mansion in Pleasanton, California.

All told, Morgan worked for Hearst for the next 28 years. He rather vaguely instructed her to build "something that would be more comfortable" than the tent-style camping previously on site. Morgan became deeply involved in the ongoing construction, from the necessary infrastructure to the small artistic details now on view at Hearst Castle.

Hearst Castle is actually a complex of ornate buildings

Calling it "Hearst Castle" is a bit of a misnomer. Sure, there's the large and highly decorated central residence that's often referred to as "La Casa Grande," but this behemoth of a building is far from the only structure that demands your attention at Hearst Castle. It is hard to ignore, of course, given its ornate Mediterranean Revival style packed with sculptures, architectural elements like a marble balcony, and multiple bell towers, per Britannica.

Additionally, there are also three guest houses on the grounds. As "Julia Morgan: Architect of Beauty" reports, these were originally given the admittedly uninspired names of "A", "B", and "C." That didn't last long, however, and the guest houses (which match the main house in decorative style if not sheer floor space) were more poetically renamed Casa del Mar (House of the Sea), Casa del Monte (House of the Mountain), and Casa del Sol (House of the Sun).

According to Britannica, Casa del Mar has a total of 5,350 square feet of space, while Casa del Monte is the smallest at 2,550 square feet and has a mere four bedrooms (compared to the 38 bedrooms and 115 rooms total of La Casa Grande). Oh, and if it weren't enough to have a guest house that dwarfs many other family homes, the estate also had a zoo, two elaborate pools, and acres upon acres of gardens and grounds.

Hearst Castle wasn't easy to build

Even a cartoonishly rich businessman and newspaper magnate like William Randolph Hearst was in the 1920s couldn't magically snap his fingers and summon Hearst Castle out of thin air. The truth is that the construction of the complex was tough work (though it's doubtful that Hearst himself was ever seen hefting building materials around the site). With a remote location and demanding construction costs, it was difficult to both retain workers and simply get the work done. Per "Julia Morgan," the landscape was steep and largely undeveloped, requiring a purpose-built dirt road to transport workers and equipment up the hill and debris like dynamite-blasted rock back down.

Morgan also had to design a special water system that supplied purpose-built reservoirs with collected rainwater and spring water. And, as if that weren't enough, there was the commute. KCET reports that Morgan would typically take the weekend to visit the site, leaving San Francisco and traveling 200 miles by train to San Luis Obispo. From there, she would take a taxi 45 miles to the growing edifice of Hearst Castle in San Simeon.

It was originally going to be a family home

William Randolph Hearst originally meant to live at Hearst Castle with his wife, Millicent, and the couple's five sons. According to Hearst Castle, the pair had been married since 1903, after a 34-year-old Hearst became interested in the teenage Millicent Willson as she performed on Broadway. As the mansion came to fruition, it seemed as if things were going decently enough. The whole family camped at the estate and Millicent was even involved in some of the early design decisions. But things went sour as the years progressed. Eventually, Millicent became so disturbed by her husband's affair with actress Marion Davies that she separated from him in 1926. She continued to visit Hearst Castle on occasion for a few years, but ultimately stayed in New York City while never officially divorcing.

Meanwhile, Hearst openly lived at Hearst Castle and a number of other estates on the West Coast with Davies. Slate reports that the two had met around 1918, when the actress had signed on to work with Cosmopolitan Pictures, Hearst's production company. She was a popular person, but never quite proved herself on screen and eventually retired in 1937.

At Hearst Castle, Davies became the de facto hostess for the couple's numerous parties (and also apparently did decently well for herself by investing in real estate and occasionally even supporting Hearst himself). Though she never married Hearst, Davies stayed with him until his death in 1951.

Hearst Castle became known for grand parties and big-name visitors

Once it was completed, quite a few famous guests stayed at the castle, including such 20th century notables as actor Clark Gable, author P.G. Wodehouse, and actress Greta Garbo (via Smithsonian Learning Lab). Charlie Chaplin was also a frequent guest, though his association with William Randolph Hearst got pretty dark after the 1924 death of a producer aboard Hearst's yacht. As the rumors went, per The Vintage News, Hearst had become enraged after Chaplin (or maybe it was the producer) made a pass at Marion Davies. Those whispers, however, never became anything substantial and both Hearst and Chaplin steered clear of any real accusations.

On what were assuredly happier occasions, Hearst and Davies became known for their lavish parties, some of which required guests to come to Hearst Castle in costume. "William Randolph Hearst: The Later Years" reports that party invites were often pretty formal and included prepaid train tickets to make it out to the remote estate.

Getting into Hearst Castle wasn't always easy

As even members of the Hollywood elite learned, securing one of those formal invitations to Hearst Castle could be pretty tricky. And, assuming you wanted to be a regular at the opulent estate, you had to take advantage when the time came. Katherine Hepburn later said she regretted turning down what would be her one invitation, even going so far as to call it her biggest career mistake (via Variety).

If you did get that invite and responded in a timely fashion, physically getting to the remote location could still mean a serious trek. For many, that involved a long train trip, though "William Randolph Hearst" notes that at least the invite typically included both a train ticket and a private sleeping car. Once at the station, guests would also undergo a 45-mile drive (via limousine, of course), just to arrive at a guard station with armed personnel waiting. Actress Colleen Moore recalled that the guard checked that they were actually supposed to be there and then let them pass (via New Yorker).

The five mile drive up to the estate was necessarily leisurely, in part because of the exotic animals wandering around the estate. Even then, guests weren't exactly expected to pile out of the cars and greet Hearst right away. More often, a housekeeper and a set of servants would escort guests to their rooms and help them unpack.

Visitors to Hearst Castle enjoyed lavish perks

Perhaps, if you were among the ranks of the Hollywood elite of the 1920s and 1930s, rubbing elbows with the likes of Greta Garbo and Clark Gable, the sorts of perks offered at Hearst Castle might seem at least passingly familiar. But, then again, even Garbo didn't have an estate with a private airfield.

William Randolph Hearst did, though. According to Hearst Castle, he actually had two airstrips, which could be approached from any cardinal direction. Well-known pilots of the time, including Amelia Earhart and Howard Hughes, visited his ranch and landed there. Today, the airfield is still owned by the Hearst Corporation media company.

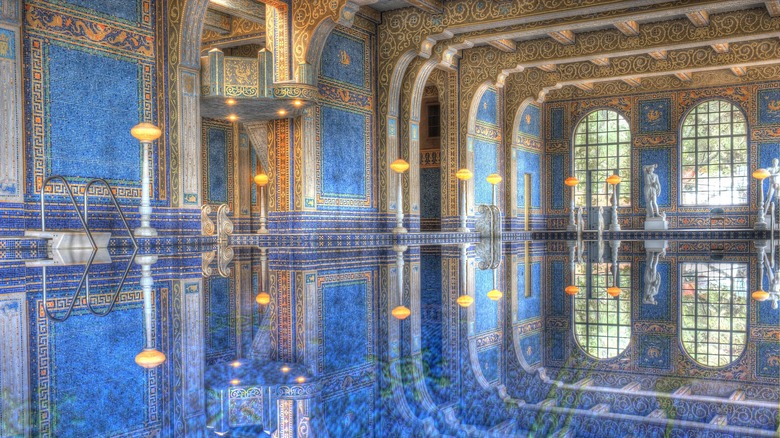

Guests could enjoy two spectacular pools, known as the Neptune Pool and the Roman Pool, per Hearst Castle. The outdoor Neptune Pool underwent a few design changes over the years, but ultimately became a large recreational space that can hold about 345,000 gallons of water. The indoor Roman Pool is smaller and was modeled on ancient Roman baths, complete with glimmering glass tile mosaics and modern copies of Greek and Roman statuary. And then there was the private wine cellar, which was open for many years regardless of Prohibition. Though Hearst was publicly skeptical, he was also known to strictly control alcohol consumption as his parties, to the point where boozier guests would sometimes be asked to leave.

Hearst wanted to turn it into a live-in museum

Once called the "great accumulator" by British art dealer Joseph Duveen, William Randolph Hearst had a passion for collecting fine artwork and installing it throughout the estate. He said that he wanted the castle to be "a museum of the best things that I can secure" (via "The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst").

And, say what you will about Hearst's business practices or private life, or even how he acquired all that art, but you must admit that he had the taste and funds to select some truly beautiful pieces. Some of the most impressive artworks on display at the estate are housed in the main residence's expansive assembly room, according to Hearst Castle.

These include an 8-foot-tall 17th century painting of the Annunciation, as well as an 18th century copy of a Greek statue that is hailed for its artistry in its own right. And then there's "The Continence of Scipio," a series of 16th century tapestries that Hearst was so focused on displaying that the design of the Assembly Room was at least partially inspired by these textile masterworks (via Hearst Castle). Wandering around the estate, you'll also encounter multiple ancient Egyptian statues of the fierce lion-headed goddess Sekhmet, medieval and Baroque ceilings, and an ancient Roman sarcophagus.

Hearst Castle once had a private zoo

Technically called the Hearst Garden of Comparative Zoology, the estate's animals were once part of the world's largest private zoo. And, perhaps unsurprisingly by the time it began in 1924, it was up to architect Julia Morgan to design the animal enclosures and overall zoo (via "Julia Morgan").

The zoo itself was actually divided into two main areas, reports Hearst Castle. One was a series of enclosed spaces meant to house the more large and dangerous animals, such as lions, jaguars, chimpanzees, and one elephant. Other animals were allowed to roam a larger fenced-in area. These included zebras, camels, a number of different antelope and deer species, and kangaroos, just to name a few. During the 1930s, there was even a veterinarian on staff to take care of the many different species on William Randolph Hearst's estate. Some guests were even obliged to wait for animals passing across the roadway, as the non-human inhabitants were typically given the right of way.

The zoo was taken down between 1937 and 1958, starting with Hearst's financial troubles in the 1930s. Some animals were transferred to zoos, while others were sold. However, some traces of Hearst's private zoo remain even to this day, namely zebras that can still be spotted near the estate.

Hearst Castle was parodied in 'Citizen Kane'

The fictional story of Charles Foster Kane was obviously based on William Randolph Hearst, reports the New Yorker, though "Citizen Kane" did take some liberties with the details. For instance, the film depicted the castle built by protagonist Charles Foster Kane (who just so happened to be a ruthless newspaper magnate who abandoned his wife for an actress) as a deeply ominous structure. It was almost like a gothic estate rather than the opulent, sunny Mediterranean-inspired complex actually built under Hearst's direction.

Hearst himself took the rather obvious and not exactly flattering depiction of his life poorly and banned screenings of the film at his estate. Given that Hearst and Davies regularly held movie nights for their guests, this was a pretty significant snub. He also tried to get the film shut down or at least forgotten. Per PBS, Hearst and his friends in the film industry effectively blacklisted the film and its creator, the wunderkind Orson Welles.

Though Hearst's scheme to buy the negative of the film and burn it was unsuccessful, their other efforts were. With the film smeared or ignored in Hearst's newspapers, Welles accused of communist ties, and exhibitors intimidated into dropping "Citizen Kane" from marquees, the movie languished for many years.

Mounting debt slowed the growth of Hearst Castle

Though construction continued piecemeal until the late 1940s, the Great Depression put William Randolph Hearst into dizzying debt and slowed the work on Hearst Castle. And it was, by all appearances, quite a fall from financial grace. According to the Washington Post, Hearst, who was once an incredibly influential voice in 20th century American media and whose circulation war with fellow newspaper man Joseph Pulitzer may have stoked the flames of war, was in a bad way by the late 1930s. He got $126 million in debt, was accused of dodging taxes, and had begun selling bits and pieces of his estates and art collection to make up the difference.

Though he tried to sell off parts of his estate or other holdings to finance construction, it wasn't quite enough. PBS reports that, in 1937, Hearst told Morgan to "stop work entirely at San Simeon." Hearst occasionally picked up the work over the next decade, but his and Davies' move away from the estate after his 1947 heart attack was the real end of building there. Hearst would die in Beverly Hills, far away from his castle, in 1951. Today, it's a local landmark and museum that's open to the public, where tourists can wander through the halls and gaze at the artworks previously only reserved for the view of Hearst, Davies, and their guests and staff.