The Untold Truth Of Carnivals

Ah, carnivals. You wander aimlessly, running into literally every one of your exes and a bunch of oddball mysterious locals whose names you never remember but who seem to know all about you. You get sick on junk food and hastily assembled rides and drive your significant other to poverty trying to win you a terrifying knockoff stuffed animal. Maybe a fortune teller machine will turn you into an adult and you'll have wacky adventures.

It's not all fun and games, though. Let's look into the lesser-known history of just how these carnival things began.

Carnivals had a religious background at first

Throughout most of this article, we are going to use the more modern (and more American) definition of "carnival"—traveling, annual or seasonal affairs with games, rides, and sideshows. However, the concept and name go back centuries and have deeply religious roots.

The term "carnival" is generally assumed to be a Medieval-era Latin portmanteau that roughly means "say goodbye to the flesh" or "to remove the meat." While that sounds like something you'd expect a spooky pale bald guy with pins in his skull to hiss at you after you unlock his accursed puzzle box, it's a reference to the Catholic tradition of Lent.

During Lent, you are expected to give up meat and other vices until Easter. So, religious people, liking themselves some vice just like the rest of us, made the day before Lent begins into a feast of indulgence of everything you planned to give up. You may already recognize this as the backstory of Carnival in Brazil and of Mardi Gras. Most of our wildest, most anarchic holidays have roots in deeply religious Medieval peasants deciding they needed a handful of days a year to forget their lives as deeply religious Medieval peasants.

Fairs and annual fairs have been around in America nearly as long as it existed

While traveling carnivals with rides and games and such are an invention of the late 19th century, annual festivals in America with their own bizarre traditions and rituals that didn't quite catch on appeared as soon as people had time not dying of smallpox to party. The first Mardi Gras happened literally right when the explorers Iberville and Bienville got off the boat in what became New Orleans in 1699. They pretty much staked their claim and declared, "This will forever be the spot where many ruinous hangovers, awkward morning conversations, and incriminating photos will occur."

Even earlier, the Pocomoke Fair is considered the earliest American annual city fair, originating in 1641. It was held in Old New York, which was once New Amsterdam. Why'd they change it, we can't say. People just liked it better that way.

Colonial American city fairs and festivals were more of the "harvest festival" variety than what we would think of as a carnival now. Like, hay rides and stuff. Were hay rides ever fun? Why did people think hay rides are fun? It was a much simpler time back then.

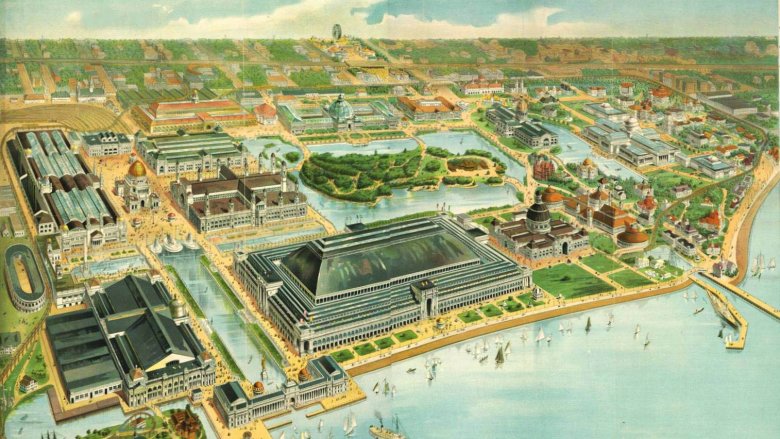

The modern idea of carnivals began with the Chicago World's Fair

It's estimated that one out of every four Americans alive at the time attended that Chicago World's Fair during the six months it was open. In modern terms, that's the attendance of this year's Super Bowl plus this year's Wrestlemania, multiplied by 40. So, you know, a lot of people.

The World's Fair was famous for the debuts of all sorts of technical marvels and even a performance by Nicola Tesla, who designed the AC lighting for the whole fair. However, let's forget about all of that and focus on the far western side of the map, literally on the other side of the railroad tracks from the rest of the showcases. This was the Midway Plaisance carnival, which literally every carnival and fair in America ever since is in some way based on structurally. It had the rides, it had the sideshows, it had the food vendors, and even modern carnivals use the term "midway" to describe the arrangement of amusements influenced by this particular fair.

Honestly, the electronic gadgets in the fair were probably cooler, but it was the carnival configuration that lived on.

The first Ferris Wheel was designed to be Chicago's Eiffel Tower

One of the many things to debut at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair Midway Park was the Ferris Wheel, an amusement that would become a staple of nearly every carnival since. The Wheel itself has a weird and dramatic history befitting its designer's goals, which were to erect a monument in Chicago that would rival the Eiffel Tower.

Now, this wasn't the first such ride to exist, but George Washington Ferris Jr.'s (yes his real name) wheel was a whole other level from earlier dinky roundabouts. It was 250 feet in diameter, and its 71-ton axle was the world's largest hollow forged piece of metalwork in history at that point. Now, that's nowhere near as tall as the Eiffel Tower, but until old Eiffel can unfold into a transforming robot, the Ferris Wheel had the advantage of impossibly massive moving parts as a testament to its technological legacy.

Ferris pretty much bankrupted himself running safety tests. He was so broke when he died that the funeral director put a lien on his remains because he had no other assets left to seize, and it took 15 years of litigation before the ashes were turned over to his brother. The wheel itself was used again in the 1904 St Louis World's Fair and then was dynamited to bits two years later because it was too expensive to maintain.

So yeah, there isn't exactly a happy ending to this tale. However, it's a testament to Ferris's grand vision that even a tribute wheel erected on Chicago's Navy Pier in 1995 it was still 100 feet shorter than his original design.

"Magic Lantern" shows predated film

We've all heard the tale (that's probably not true) about the audience fleeing the theater at one of the early short films because they thought the train was coming at them. It may be surprising to learn that these same audiences may have already been familiar with rudimentary animation from carnival sideshows in the form of what were called "magic lantern" shows. Part mechanical and part shadow-puppet, they were projected on the wall or through a special visor using a strategically placed lantern.

Much of the fare was family-friendly historical vignettes or replications of foreign landscapes. However, it wasn't uncommon for them to depict gruesome horror or even scenes for very adult audiences. Because sometimes, day-to-day life in the 19th century was so stressful, the only way to unwind was to watch psychedelic puppets boink and/or murder each other. Simpler times and such.

A lot of famous "Wild West" figures spent their twilight years in carnivals

The era of carnivals picked up around the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, when the "Wild West" of frontiers and ranchers and prospectors had wound down and was quickly being forgotten. Many figures of the Frontier Era who were still alive and still looking for a source of steady whiskey money saw this as an opportunity to tell their stories and hold on to relevance in a quickly changing world.

One of the primary figures to cash in was "Buffalo" Bill Cody, whose "Wild West" show raked in so much money that he subsequently spent hand-over-fist in local saloons, to the point that literally nobody knows exactly how many millions of dollars he threw around. For the time, the show was surprisingly progressive, at least in cast. It included women gunslingers like Annie Oakely and Calamity Jane, black and Hispanic cowboys like Bill Pickett and the Esquivel Brothers, and Native Americans like Chief Red Cloud and Geronimo to provide a wide range of frontier historical experience.

Of course, not every Wild West figure wound up with such a glorious and profitable carnival career. The corpse of train robber Elmer McCurdy spent 60+ years as an anonymous mummy in a series of carnival haunted houses after a grave robber stole him. He didn't wind up with a proper burial until he was discovered by the crew of the television show The Six Million Dollar Man in 1977. Okay, that's pretty buck wild.

The "Tunnel Of Love" was a product of older, more uptight times

At this point, references to the formerly popular carnival attraction "Tunnel of Love" are cartoon anachronisms that hardly anyone under the age of 60 gets. What is it? What goes on in there? Considering only a handful are left and they're attended by literally the same people that went to them in the 1950s or earlier, most of us may never know. But hey don't worry, we've got the scoop on this ride that got your grandparents' motors revving. (Sorry for that image.)

It's a tunnel. A dark tunnel. That's ... mostly it.

The ride used to be called "The Old Mill," but ride operators realized people were taking advantage of the dark tunnel to make out, so they wised up and cut to the chase with their advertising. In those days, public displays of affection by unmarried couples were taboo, and a dark semi-private ride was all the excuse teenagers and other romantically inclined folk back then needed to get freaky. Sometimes, the ride would show romantic vignettes and play soft music, and sometimes there would be gruesome scenes with monsters popping out of the shadows to encourage dates to snuggle into their partner for safety.

If you're a fan of corny retro things and want to see what the fuss is about, there's a whole group dedicated to documenting the remaining rides and the experience. They're probably not as exciting or fun as you're picturing it, but kids these days seem to enjoy anything ironically, so who knows.

The 1904 World's Fair changed food forever

What are foods you typically associate with carnivals? Somewhere in the top five items, you will usually find hot dogs, hamburgers, and cotton candy. What if we told you all three of those items had their popular debut at the same event—along with Dr. Pepper, yellow mustard, and ice cream cones? All became known to widespread American audiences thanks to the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis.

Not all these items were invented there, but they definitely wound up popularized there. And, really, is a hot dog without yellow mustard even a hot dog at all?

Also popularized by the 1904 World's Fair: puffed cereal. Okay, so not every item became a carnival hit.

"Freak Shows" are actually still around, but much different than they used to be

"Freak shows" are usually discussed as a product of an older, darker, and uglier time, and for good reason. Showcasing physically handicapped and unusual individuals to be gawked at ridicules and dehumanizes them. However, it wasn't all the gruesome affair that films like David Lynch's The Elephant Man would have you believe. Many sideshow regulars made pretty decent incomes for themselves in an era when they'd have been considered unemployable by general society.

Perhaps this sort of traditional outsider camaraderie appeal inspired the recent resurgence of modern freak shows starting in the 1990s and continuing to this day. These days, most involved are extreme performance artists, folks with extensive body modification, or burlesque or gender-non-conforming performers. They swallow swords and shards of glass, breathe fire, and suspend themselves from hooks. It's pretty much the same kind of stuff that happens at parties attended by that weird IT guy in your office who wears leather bondage bracelets and thinks nobody notices.

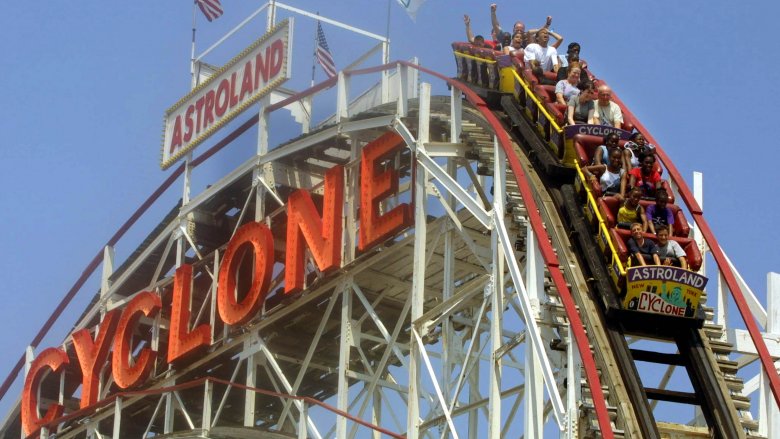

The original roller coaster was really, really slow

Considering it's not unusual for a modern roller coaster to top out at 90 or more miles per hour, it's pretty hilarious to imagine carnival-goers of 120 years ago hopping on one that went barely faster than a brisk power-walk, hardly enough to jostle your mandatory 1880s top hat/monocle ensemble. But that's what the 12,000 people a day who rode The Switchback Railway paid their hard-earned old people nickels for.

It was called "Switchback" because that's literally what you had to do. For a nickel, you manually climbed up a staircase to the top of a 50-foot tower, boarded the car, and slowly coasted down a slight incline to the bottom, where you'd then walk up another 50-foot tower, get on a second car, and slowly coast back.

Those of us who barely remember high school physics may recognize this as doing all the work for the roller coaster for the payoff of a trip half as fast as an average golf cart. Those of us who barely remember elementary school recess may recognize this as a slide but with a bunch of extra pointless steps.