The History Of Epiphany Explained

Epiphany is a widely anticipated and celebrated holiday around the world, especially among Catholics and Orthodox Christians. For children, it is a second Christmas of sorts, an opportunity to receive more gifts if they have been good and coal if they have been naughty. For religiously observant adults, the holiday is an opportunity to celebrate and ponder the glory of Jesus' various manifestations as God as they appear in the Bible (via the Catholic Commentator).

The history of Epiphany, however, is complicated. New Advent reports that early Christians often disagreed about the exact meaning of Epiphany, and it did not become a universal holiday until it clashed with the now-much more famous celebration of Christmas. Even though the two holidays competed for celebrants, they eventually came to coexist. Today, Epiphany is celebrated among diverse cultures, all of which have added their own traditions to this celebration of the first manifestations of salvation to mankind. Here is the history of Epiphany explained.

It's all in the name

The meaning of Epiphany is encapsulated in the name of the holiday. According to Bible Hub, the Greek word epiphania means "manifestation" or "glorious appearance." "A History of Greek Religion" describes the appearances and interventions of Greek gods in the mortal realm as epiphanies, while the North American Lutheran Church notes that the word also had secular usage. The public appearance of a ruler with all the fitting pomp and ceremony was also considered an epiphany.

In Christianity, the word epiphany has multiple meanings that tie into the original definition. The Bible uses the word (translated in the New International Version as "appearance") to refer to Jesus' first manifestation as God and his final coming. Thus, the celebration of the Epiphany, according to Britannica, in the Christian tradition celebrates one of several appearances or manifestations of Jesus Christ as God on earth, which according to tradition, falls on January 6. It is one of Christianity's oldest feast days. According to the Catholic News Agency, Epiphany even predates the celebration of its much more popular cousin, Christmas. Interestingly, the first time any sort of feast resembling epiphany on January 6 appears in the written record is in a pagan context, not a Christian one.

Pagan Egyptian origins?

According to the North American Lutheran Church (NALC), one school of thought argued that Epiphany originated in pagan Egyptian rites related to the winter solstice. Roman authors noted that pagan Egyptians celebrated the birth of the god Aeon to a virgin named Kore. This story mirrors the birth of Christ, who was born of the Virgin Mary. Christian converts turned this celebration among others into a "feast of the light" commemorating Jesus' birth and baptism, when he openly manifested as God for the first time.

While the pagan origin story of Epiphany is certainly compelling, the NALC notes that there is an alternative hypothesis that Christians consider more likely. Early Christians, using the Roman Julian calendar, celebrated the date of Jesus' conception on April 6. It is also believed that Jesus was born, baptized, and died on the same day, perfect timing in a perfect life. This timeline would make Epiphany's overlap with pagan Egyptian holidays a coincidence.

Ultimately, Epiphany's origins are not known with absolute certainty. The sources are virtually silent on the holiday's celebration until well after the first century A.D. In fact, the holiday only appears in passing in the textual record beginning in the mid-fourth century A.D., after which more detailed descriptions of the holiday's purpose and significance have been preserved.

First appearance

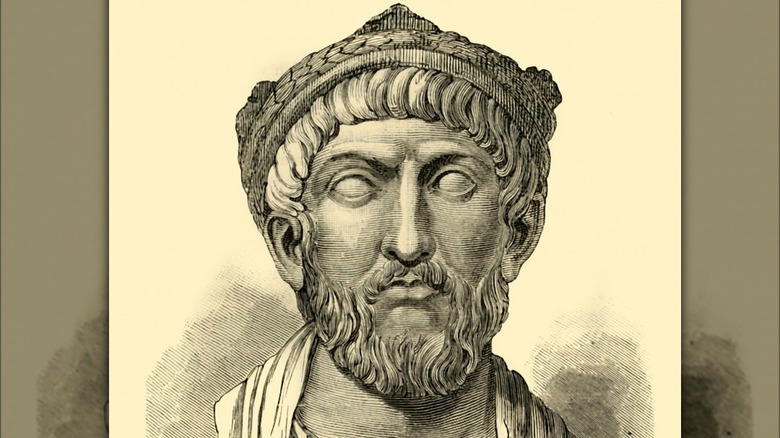

While there are numerous pagan celebrations that occurred around the time of Epiphany, according to "The Liturgy and Time," the Christian holiday was not attested in writing under this name until 361 A.D., over 130 years after the attestations of pagan January 6 celebrations. In his "Rerum Gestarum," Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that Emperor Julian the Apostate, despite privately renouncing Christianity, outwardly professed the religion and attended Epiphany celebrations to conceal his apostasy. The Liturgy and Time notes that the celebration, despite its late attestation, was probably already a major feast day in the Western Roman Empire. If it had been a minor celebration, it is unlikely that Julian would have felt compelled to observe it.

Marcellinus' narrative establishes the importance of Epiphany. Unfortunately, he does not tell his audience much else about the holiday other than its January celebration. Perhaps the exact event commemorated on Epiphany would have been obvious to his audience, but because Epiphany has developed over the centuries, it cannot be certain the Epiphany of 361 A.D. celebrated the exact same manifestation of Christ as Western Christians do today. Now, sources are contradictory in this regard. It seems that in the Roman world, Epiphany could celebrate Christ's birth, baptism, or first miracle.

Birthday, baptism, or both?

St. Gregory of Nazianzus, a Cappadocian theologian from modern-day Turkey, provides some early evidence regarding the significance of Epiphany. In a sermon dating to 380 A.D. (via Catholic Encyclopedia), the saint refers to the holiday of the Theophany (Eastern name for Epiphany) as the "Birth-day" of Christ. But there is some confusion. The sermon was preached either on December 25, 380 or January 6, 381, which are the dates of the modern holidays of Christmas and Epiphany respectively. Gregory himself gives an answer. The celebration of Christ's birth and the Epiphany were one and the same holiday. Any mention of Christmas is completely absent. This contrasts with attitudes to the Epiphany among other early church theologians, who rejected Epiphany as a celebration of Christ's birth.

St. Jerome, writing around the same time as Gregory, agreed that Epiphany was an important and venerable holiday. The translator of the Vulgate, however, complained that many people did not know the true meaning of the holiday or what it commemorated. St. John Chrysostom voiced similar frustrations. According to this school of thought, Epiphany celebrated not Christ's birth, but his baptism (via Bible Gateway), when he is explicitly called the Son of God. Their logic was that Jesus' birth was not an epiphany/theophany because it was not yet revealed to the world that Jesus was God. Thus, Epiphany could not commemorate his birth. But in the pre-modern world, doctrinal unity was more of a goal than a reality, so local celebrations differed in the commemoration of the holiday.

Which is it?

While the great early theologians wrote primarily on how Epiphany should be celebrated, ordinary people continued celebrating as they saw fit according to their own traditions. In the Holy Land, despite criticisms from the aforementioned theologians, people commemorated Christ's birth, as documented in the Pilgrimage of St. Silvia (aka Egeria) of Aquitania. In her pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Egeria described an eight-day celebration that took place in and around the Great Church (aka the Holy Sepulchre). The octave suggests that she can only be describing Epiphany, which according to Harbor of Faith and Morals was celebrated as an eight-day feast as recently as 1955.

Egeria's description contains one key detail that attests to Epiphany as a celebration of Christ's birth in the Holy Land. She mentions that the church in Jesus' birthplace Bethlehem (probably the Church of the Nativity) was heavily decorated for Epiphany. Monks, priests, and faithful would all keep a vigil in the town until dawn, presumably in anticipation of Christ's birth. It is unlikely that Bethlehem would have played a major role in a celebration of Jesus' baptism, which occurred far from Bethlehem in a place called Bethany Beyond the Jordan. Egeria's account speaks to local differences in Epiphany, which never quite became a uniform holiday across the Christian world, in part due to the holiday's conflict and conflation with Christmas.

Conflict with Christmas

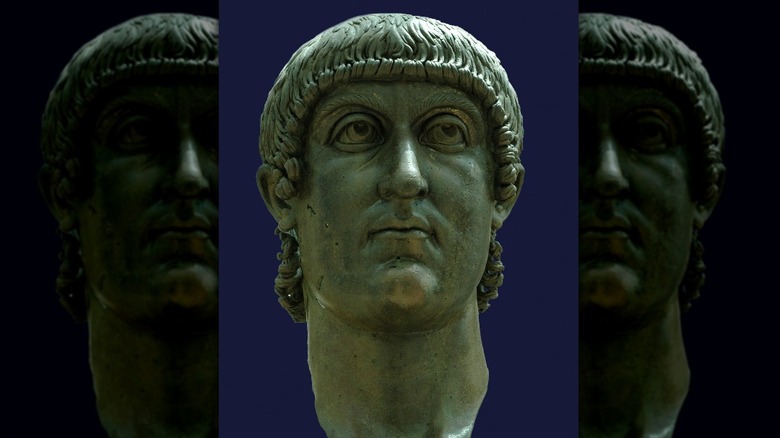

Epiphany today is intricately tied to Christmas, so to explain Epiphany's meaning, a short discussion of Jesus' birth is in order. A footnote in Pilgrimage of St. Silvia notes that according to St. John Chrysostom, the celebration of Christmas began in Antioch and Syria and spread West into the Roman Empire. Although, according to History Today, allegations abound that the Roman emperor Constantine created Christmas to replace an older pagan feast, the truth is actually more complicated and entails the competition between those who celebrated Christmas and those who observed Epiphany.

Despite Christmas' alleged pagan roots, early Christian communities in Italy had already settled on the December 25 date well before Constantine. Writing in 204 A.D., approximately 100 years before Constantine, St, Hippolytus (via Vatican Insider) considered Jesus' birthday to be December 25. Coincidentally, it just happened to line up with the pagan celebration of the birth of the sun. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Christmas was the main Nativity celebration in the Western Roman Empire. Therefore, celebration of Epiphany as Christ's birth was considered redundant and in some areas, was not observed at all. In response, Eastern churchmen repeated the accusation that Western Christians used Christmas as a replacement for the birth of the sun in place of Epiphany, effectively accusing them of paganism. But as the Christian world coalesced, Epiphany, as Ammianus Marcellinus noted in 361 A.D., arrived in Western Europe too. But it would be adopted in celebration not of Jesus' birth or baptism, but of his very first revelation as God to the gentiles.

Christ's manifestation to the gentiles

According to Newsweek, Epiphany today is popularly known as "Three Kings' Day." This is the result of a compromise that resulted in Epiphany being adopted into the Western Christian tradition, but not at Christmas' expense. When Epiphany was adopted in Western Europe it maintained the holiday's connections with Christ's birth, but did not commemorate it. Instead, European theologians developed an intense fascination with the role of the Magi in the Nativity story. According to the Encyclopedia Iranica, these men were Persian Zoroastrian priests who came to adore Jesus in his manger.

According to Focus on the Family, the Magi hold the distinction of being the first recorded non-Jews (gentiles) to see Jesus and pay homage to him. So while in the Eastern world, Epiphany was a commemoration of Christ's birth and later, baptism, in the West, it was also a celebration of Jesus' manifestation as the "Light of the World" (via Bible Gateway) to all people. The National Shrine of St. Jude notes that the Magi were the first gentiles to heed God's call and go and adore the Messiah, and today, it serves to remind Christians that they must make the decision to seek Jesus and follow him, regardless of the risks. After all, the Magi ran considerable risks to their own safety travelling from their faraway homelands in the Iranian world to the tiny Judaean town of Bethlehem.

The holiday crystallizes

In Catholic Europe, Epiphany's association with the Magi stuck, making it one of the most important and celebrated holidays to this very day. According to Catholic News Agency, the Catholic Church separated Christmas and Epiphany into two separate holidays. Catholic Harbor of Faith and Morals explains that Epiphany officially became an octave, just as The Pilgrimage of St. Silvia had described it four centuries earlier. It ran from January 6 to January 13, a celebration that directly continued the 12-day Christmas season that ended on January 5. In 1955, it was cut down to one day. But this one day has absorbed countless European traditions, many of them pagan, that make Epiphany one of Europe's most colorful and fun celebrations.

The traditions associated with Epiphany are numerous. According to Aleteia, Spain and France both celebrate with the baking of the King's Cake, which contains a small figurine of Baby Jesus. Italian legend tells of an old lady named Befana. According to Italia Living, this woman, often portrayed as a witch, stubbornly refused to accompany the Magi to see Jesus. When she finally changed her mind, she got lost and never found him. So, every Epiphany, she gives the gifts intended for Jesus to Italian children instead. Bad children get coal. According to Medievalists, Catholic Eastern Europeans write the initials of the Magi above their doorways as a blessing for the home. The English-speaking world developed its own traditions, which are best known from one of William Shakespeare's romantic comedies.

The Shakespeare connection

According to MIT, Epiphany in England overlapped with another celebration called Twelfth Night, the basis of the play by William Shakespeare. Twelfth Night was technically the evening of the last day of Christmas right before Epiphany, but the two were considered a single celebration. According to the National Trust, the quintessential Elizabethan holiday tradition was called "wassailing," very likely a much older custom with pagan origins. People would go out to the apple orchards and sing to the trees in hope of ensuring a good harvest season. They would then get together and drink hot spiced alcoholic cider called wassail. Naturally, where there was alcohol there was also much revelry and celebration.

According to the Tudor Society, the Tudor upper classes liked to throw large parties in commemoration of Twelfth Night and Epiphany. But these were not particularly reverent of the holiday's original meaning. Under Henry VIII, raucous masked balls became the norm at the Tudor court. According to the Utah Shakespeare Festival, a favorite holiday tradition involved cross-dressing and role-switching between the sexes and social classes. This aspect of English Epiphany comes out in Shakespeare's play. Today, according to Mardi Gras New Orleans, the raucous traditions associated with Epiphany continue in the form of Carnival, which begins with Epiphany as a time of celebration before Lent. It is celebrated in America in New Orleans with a parade through the Old French Quarter, and as expected, is just as raucous and wild as its Tudor (and other) antecedents.

Epiphany in the New World

The development of Epiphany did not stop in Europe. When Christianity made landfall in the New World, it quickly spread among the inhabitants, who picked up Epiphany tradition and made them their own. According to Zenger, the best known version is el dia de los reyes, celebrated most notably in Mexico and the rest of Latin America. The holiday is mostly for children, who write letters to the Three Kings asking for gifts. These letters may be placed in shoeboxes or shoes. Puerto Rican children go farther and place grass inside the shoes. In case the Magi's animals are hungry, they can rest and find sustenance while their owners leave gifts.

In South America, especially in places with large slave populations, a second Epiphany tradition developed. According to Chilean radio station Vilas, African slaves maintained a strong devotion to the magus Baltazar, who allegedly was a black African. He was considered their protector, and slave owners would give their slaves the day off from work to rest and pray. Today, it is still celebrated in South America. According to Zenger, in places such as Paraguay, processions of music and dance are held in honor of Baltazar, who gave many slaves hope that they too could find salvation and dignity in the next life.

Taking the plunge: Epiphany in Eastern Europe

Because the Orthodox Churches in the East Slavic world (e.g. Russia, Ukraine, etc.) use the Julian Calendar (explained via Holy Trinity Cathedral) rather than the Gregorian calendar, their Epiphany, which is still referred to as "Bohoiavlennia" (via Encyclopedia of Ukraine) falls on January 19th. According to What is Ukraine, Orthodox Christians and Eastern Catholics, in commemoration of Jesus' baptism in the Jordan, are sprinkled with holy water drawn from local bodies, which is believed to obtain supernatural qualities on that day once a priest blesses it.

After, as part of the festivities, things get truly frigid. Russians (via Moscow Times), Ukrainians (via RFERL), and others immerse themselves in freezing water that has been blessed. According to NPR, the celebration can begin as late as 9 pm, although it can also happen during the day. The bathers strip down to their bathing suits and immerse themselves three times in honor of the Trinity, which is supposed to cleanse the soul, making it a baptism of sorts. I

n the colder climes of Northern Russia, people cut cross-shaped pools into lakes and rivers and immerse themselves in those. Even Vladimir Putin takes part, as reported by CNN. Although the practice might seem crazy to foreign observers, practitioners report a feeling of a rush of energy, and paramedics are always on hand in case an emergency develops.

Baptizing the Ark: Ethiopian Timket

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Ethiopia holds the distinction in the Christian world as being the final resting place of the Ark of the Covenant, believed to be in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Axum (via Britannica). Although the original is off limits to everyone except for one guardian monk, Selamta Magazine notes that the Ethiopian Orthodox Churches across the country keep replicas of the Ark for the faithful. This replica is the central part of Timket, the Ethiopian Orthodox celebration of Epiphany.

Timket is celebrated throughout Ethiopia's Orthodox communities, but the flagship celebration takes place in the old city of Gondar in northern Ethiopia. This three-day celebration begins with a parade and vigil and ends with a bath. The colorful processions make their way to the Gondar landmark called Fasilides Bath (via Brilliant Ethiopia). Here, the faithful take part in a vigil in anticipation of Jesus' baptism. In the morning, the Gospel of Jesus' baptism is read. The priests bless the pool of water and immerse the replica of the Ark of the Covenant.

According to Feeding on Christ, the Ark of the Covenant is a physical representation of Jesus, so the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is commemorating Jesus' baptism by baptizing a representation of him. Penguin Travel explains that the faithful then renew their baptismal vows by jumping into the pool and celebrations ensue with lots of food, music, and merriment.