Songs You Didn't Know Had Ties To Slavery

Dig deep enough into any example of American culture, and you'll inevitably find racism. It's not surprising — this is a country that legally sanctioned human slavery for nearly the first century of its existence. But it's especially disturbing when it's very well-buried and not at all obvious. There's just something horrifying about suddenly realizing that a favorite piece of your life is tainted.

That goes double for the songs that make up the soundtrack of our lives. In the modern day, you can rest assured no song with any connection to racism or that celebrates (or even merely accepts) slavery would be released, but that wasn't the case in the past — sometimes the relatively recent past. Music, after all, reflects and comments on the time and place it's written in, and for most of American history, the "peculiar institution" of slavery has dominated the public discourse.

Just because a song has a connection to slavery doesn't mean it's not a bop, however — and an earworm is one of the hardiest parasites in the universe. Once a catchy song has invaded your consciousness, it's almost impossible to get rid of it, which helps explain why the songs on this list continue to be familiar to everyone despite their unsavory background. Here to ruin your day are the songs you didn't know had ties to slavery.

The Ice Cream Truck Song

If there's one thing that binds us together as a society, it's a love for ice cream. Eddie Murphy knew what was up back in 1983 when he crafted one of his greatest comedy routines around the pandemonium that erupts when the ice cream truck drives into your neighborhood, and, as The New York Times notes, the bit still stands up. Which means that for generations, kids have associated the simple joys of ice cream with a "virulently racist" song (via NPR).

As NPR reports, the iconic song that most ice cream trucks used to play was based on the classic tune "Turkey in the Straw." But that song didn't become nationally popular until it was featured in blackface minstrel shows. The moment you see the words "blackface" or "minstrel," you know you're in trouble, so you can only imagine how bad it gets when you put them together. A musician named Harry C. Browne released a version of "Turkey in the Straw" with incredibly racist lyrics that describe a group of slaves enjoying a treat of watermelon (yup). Except instead of "slaves," he preferred the use of a racial slur. The Hot97 Morning Show's segment on the subject explicitly lays out the connection between Brown's song and ice cream trucks, lining up the racist lyrics with the familiar melody.

According to CNN, Good Humor stopped using the song once its connection to slavery was exposed — and RZA of Wu Tang fame wrote a new jingle for them to use instead.

Jimmy Crack Corn

Chances are you know the song "Jimmy Crack Corn," along with the ending couplet "I don't care!" The official title of the song is actually "Blue Tail Fly," according to author Michael L. Jones in his book "Louisville Jug Music." It was pretty common to hear the song in playgrounds and in schools — it's catchy and exuberant, and the "I don't care" refrain no doubt seems kind of naughty to kids. But it's also a song with a direct and obvious connection to slavery.

AZ Central explains that "Blue Tail Fly" is a story song, and the story it tells is of a slave whose master dies in an accident. The lyrics literally say "When I was young I used to wait / On the master and hand him his plate." The master goes riding, and his horse is annoyed by a swarm of biting flies and throws him into a ditch. Vox makes the point that its one of the rare songs depicting a slave as a human being — the singer has an emotional reaction to his master's death. Many people believe the song actually has the slave celebrating the death of his master — "cracking corn" could refer to a celebratory drink of corn whiskey.

Oh! Susanna

Everyone — literally everyone — knows the song "Oh! Susanna," written by Stephen Foster. Or, as noted by The Paris Review, everyone at least knows the first two stanzas — and, of course, the chorus. The second stanza is notorious for its nonsensical lyrics: "It rained all night, the day I left / the weather, it was dry / the sun so hot, I froze to death / Susanna, don't you cry."

Ha! Hilarious, innocent fun for kids of all ages. Except, as noted by Vox, the song is actually sung from the point of view of a slave, and the contradictions of the lyrics are meant to convey how stupid he is. Because he's Black. And a slave.

As noted by Digital Music News, one reason this might be surprising is due to the song's lyrics being changed frequently over the years. A verse that casually describes the protagonist electrocuting 500 other slaves (using a racial epithet to describe them) through his stupidity has been largely lost to time. And no one misses it, really, but it's important to note that this silly song was originally intended to mock and dehumanize people held in bondage.

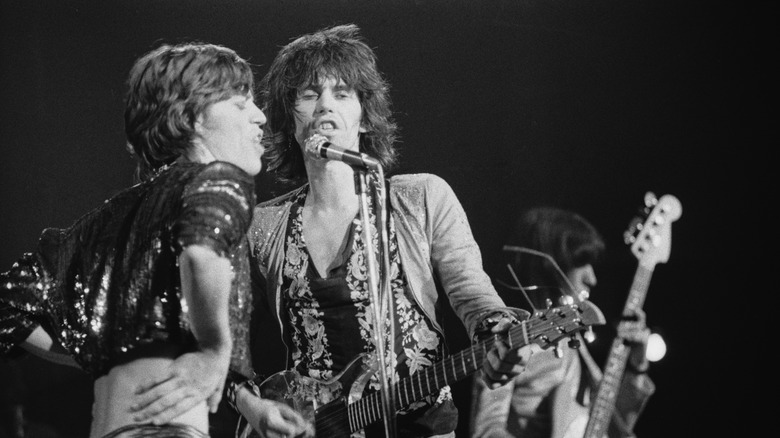

Brown Sugar

Back in 1971, The Rolling Stones were in the midst of a dominant phase in their career. As noted by Ultimate Classic Rock, their 1971 album "Sticky Fingers" is considered to be one of a five-album streak when the band was literally the greatest rock band in the world. Unfortunately, 1971 was also when they released the song "Brown Sugar."

If you're a fan of rock music, you're no doubt familiar with the song, which is one of the band's most popular compositions. But, as Vulture explains, the song's connection to slavery is not only obvious, it's also "stunningly offensive." It's widely regarded as one of the most racist and tone-deaf songs of all time, with an opening stanza that makes it clear that Mick Jagger is going to include not just racism, but cheerful references to torture and sexual assault, all with a beat you can dance to: "Gold Coast slave ship bound for cotton fields / Sold in the market down in New Orleans / Scarred old slaver know he's doing all right / Hear him whip the women just around midnight."

Jagger isn't terribly proud of the song, and according to Metro News, he has tried to make it less offensive by changing the lyrics. But as NBC News reports, after 50 years, The Rolling Stones have given up and officially retired the song from their live shows.

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

It's no surprise that many Black spirituals emerged from the horrors of slavery, beginning as songs sung communally by an enslaved people. But some songs have an even stronger connection to slavery that's not widely known — they were used as "code songs" to help slaves escaping via the Underground Railroad.

According to The Harriet Tubman Historical Society, because singing was a traditional part of the culture of African slaves, songs were frequently used to convey coded information while under the watchful eye of plantation owners. Some songs were "map songs" that gave directions escaped slaves could follow in order to hook up with the Underground Railroad. As reported by WHYY, "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" was frequently used to alert slaves that a chance to escape was coming, and so they would need to be ready to run.

Black Excellence explains some of the coded language used: The Sweet Chariot is the Underground Railroad itself. Swinging "low" means heading southward, and "home" is freedom in the North. Other songs offered practical advice concerning moving through water to stop tracking dogs from following your scent, or described constellations that helped escaping slaves navigate in the open country when racing for freedom.

Amazing Grace

"Amazing Grace" is one of the most inspiring and soul-stirring songs ever composed. In the hands of a skilled singer, it can bring out powerful emotions in anyone who hears it. And while the song itself isn't about slavery, it was written by a man who worked in the slave trade — and came to deeply regret it.

According to Biography, "Amazing Grace" was written by a man named John Newton. After a reckless youth that involved a lot of alcohol and run-ins with authorities, Newton ended up working on a slave ship bringing captured people from Africa to the New World in the early 18th century. Christianity Today reports that Newton left the sea behind in 1755 and found religion, eventually being ordained as a priest. He came to regret his role in the slave trade, believing it was a morally evil institution, and eventually did speak out against it late in life. But he didn't write "Amazing Grace" specifically about his change of heart regarding slavery. According to Literary Hub, Newton had a very specific Bible passage in mind when he composed the song — 1 Chronicles 17:16-17, often interpreted as predicting the birth of Jesus Christ.

The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down

The word "slavery" doesn't appear in the lyrics to this 1969 song by The Band, but its connection to that shameful institution is pretty clear. Written by a Canadian (Robbie Robertson), the song tells the story of a man looking back with sadness on the fall of the Confederacy. As Slate notes, some music critics argue that the point of the song is the suffering that war inflicts, not any endorsement of slavery or the Confederacy that fought for it. But as Reader's Digest reports, many in the South have adopted the song as an anthem of "The Lost Cause," and it's easy to read its lyrics as a "Gone with The Wind"-style love letter to a South that relied on slaves for its antebellum grace and beauty.

In fact, the song's association with Confederate sympathizers is so clear that many musicians in the modern day actually change the lyrics to make performing it less controversial. According to the Bristol Herald Courier, when Alabama singer Early James performed the song at a virtual concert in 2020, he caused a stir when he changed the lyrics to explicitly deplore slavery. This prompted a conversation about the subjectivity of music — after all, you are free to interpret a song any way you like, and Robbie Robertson couldn't have predicted how racists would co-opt his song. But one thing is certain: The pro-slavery interpretation is out there now.

The Star-Spangled Banner

For anyone paying attention to American history, it's not terribly surprising that our national anthem has a pretty racist pedigree. As noted by The Washington Post, its author, Francis Scott Key, could also be fairly described as pretty racist. According to Smithsonian Magazine, he owned slaves himself, and he once described Black people as "a distinct and inferior race" and was in favor of ending slavery only if all the slaves were immediately sent back to Africa.

Since most performances skip most of the song, per Dictionary.com, you might be forgiven for not realizing the song is so explicitly pro-slavery. The key verse is the third, which includes "No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave / And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave / O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave."

This verse is a reference to African American slaves who fought as Colonial Marines for the British during the War of 1812 because they were promised their freedom. Key, like any racist slave owner, was horrified and angered that the people he was oppressing might not enjoy the experience. The British kept their word, by the way — they refused to return the Marines after the war and gave them land in Trinidad, where their descendants (known as "Merikins" according to the National Park Service) still live.

Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah

On paper, there's nothing problematic about "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah." It's a joyous celebration of good weather and that generally satisfied feeling people sometimes have. The lyrics are all about sunshine and bluebirds, so what could this have to do with slavery?

The problem lies in the context: As noted by Screen Crush, "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" was composed for Disney's notorious film "Song of the South," a film so blatantly racist it hasn't been officially released since 1986. The Guardian explains that the film centers on Uncle Remus, a former slave still living on the plantation where he was kept in bondage — and looking back with real warmth and affection on those good old days. Add in some problematic depictions of Black people (who all speak in the sort of illiterate slang any racist would adore) and it's easy to see why Disney would be happy if you forgot all about this movie. According to SyFy, Walt Disney himself was well-aware of the problematic nature of the material but ignored many suggestions intended to make the film a little less racist.

The Independent reports the company has finally realized its mistake and has now also removed "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" from its official playlists in recognition of the song's connection to a pro-slavery message.

Southern Man

If you're a relatively young fan of Lynyrd Skynrd's all-time classic "Sweet Home Alabama," you might be slightly confused by the sudden reference to Neil Young that pops up in the middle of a song celebrating a U.S. state (especially since Young is Canadian). But as explained by Far Out Magazine, the shout-out stems from Young's 1970 hit song "Southern Man," which famously dragged the entire U.S. South for not just its involvement in slavery, but its continuing love affair with racism in general. According to NPR, the members of Lynyrd Skynrd were inspired to write their massive hit because they objected to the entire population of the South being painted as unrepentant racists and rednecks.

Because, frankly, that's what "Southern Man" is all about. As Rolling Stone notes, the lyrics are all about slavery and how horrible it was: "I saw cotton and I saw black / Tall white mansions and little shacks / Southern man, when will you pay them back? / I heard screamin' and bullwhips cracking / How long? How long? How?" In fact, in 2019 Young released an updated version of the song where the lyrics were expanded to include the entire United States, which Young saw as having gotten more racist in the nearly 50 years since he released "Southern Man."

My Old Kentucky Home

Every year at The Kentucky Derby, you'll hear the event's unofficial anthem, "My Old Kentucky Home," which Song of America notes is the official state song of Kentucky. Because of its longtime association with the idea of a "genteel," gracious Southern lifestyle, it might be easy to assume it either lacks any statement on slavery or racism — or that it celebrates the antebellum South in some way.

The truth is the opposite. Smithsonian Magazine reports the song was written by Stephen Foster in response to Harriet Beecher Stowe's classic abolitionist novel "Uncle Tom's Cabin," and was originally titled "Poor Uncle Tom, Goodnight." Foster was not an active anti-slavery activist, but he made efforts in his songwriting to depict Blacks as human beings and to acknowledge their suffering. As explained by WNYC News, the song is actually about a slave who has been sold to a new master. Knowing he will be soon worked to death, he is bidding a sad goodbye to both his home and his life. It's a devastating attack on slavery designed to make people think of slaves as people. At the time of its writing in the 1850s, it was often believed by racists that Black slaves lacked human emotions, and Foster's song was a rebuke to that belief.

Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen

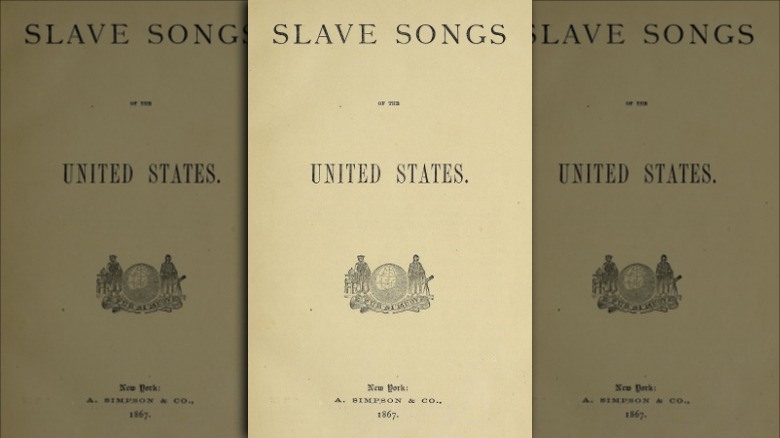

Galaxy Music Notes reminds us that if you've ever watched the original animated version of "The Lion King," you've heard Zazu singing this song to Scar while in captivity. It's often used as a humorous backdrop to comical tragedy and sadness, and it's pretty widely familiar to just about everyone.

As Ballad of America reports, the song was first written down and published after the Civil War, but it has its origins among slaves toiling in the American South. A group of abolitionists was working to teach a group of freed slaves and heard them singing the song. They recorded the lyrics and published them in the 1867 book "Slave Songs of the United States."

Although the sad tone and lament of the song seems to make perfect sense when you realize the spiritual was sung by enslaved people, Notes from the Far Fringe explains that the song is actually a coded message about escaping to the North and to freedom. When slaves singing this song sang, "If you get there before I do, Oh, yes, Lord / Tell all-a my friends I'm coming too, Oh, yes, Lord," they weren't singing about being reunited with their dead loved ones; they were singing about meeting up once they'd survived the dangerous trip to the North.