Misconceptions About Popular Animals

The animal kingdom is full of interesting creatures with incredible abilities. Unsurprisingly, humans often find facts about unique animal characteristics and behaviors to be irresistible, whether they're about the worst ways they evolved or the creepiest facts about them. These bits of information tend to get passed around as trivia, which in turn become general knowledge with frequent repetition.

That said, many of these so-called "facts" don't quite hold up to scrutiny. Take sharks, for example: There are plenty of false stories about these fish that have been perpetuated by pop culture. At best, this type of misinformation can cause people to become unfairly biased against sharks; at worst, it can severely hamper conservation efforts and cause an irrational fear of a creature that's less likely to harm people than lightning (via the Australian Museum).

Of course, sharks are far from the only animals who have been the subject of widespread misinformation. Here are some of the most common and oft-repeated misconceptions about popular animals.

Blobfish are ugly blobs

You've probably seen a photo of this fish making the rounds on social media: a misshapen blob of pink gelatinous flesh with what looks like a sad, almost human-like face. Its less-than-majestic appearance has earned it the name "blobfish" — and the dubious distinction of being the world's ugliest animal, based on the results of a poll held by the Ugly Animal Preservation Society in 2013 (via NSEC UK).

However, it's unfair to judge Psychrolutes marcidus simply based on the way it looks when it's not in its natural habitat. As Smithsonian Magazine explains, the blobfish has neither a skeleton nor muscles. It also doesn't have something that most fish have: a swim bladder, which is what helps them float and move around underwater. That's why the blobfish doesn't retain its underwater form and appearance when it's taken out of the water. In fact, it looks pretty much like an ordinary fish under normal circumstances — and in the case of the blobfish, "normal" means "downright hostile for humans."

The blobfish lives 4,000 feet under the ocean, where the pressure is 120 times greater than it is near the water's surface. This much-maligned fish's unique physiology is what helps it survive in an environment that would easily turn any human being into mush. Try to consider that before you make fun of the blobfish for not meeting humanity's arbitrary standards of beauty.

Goldfish have really bad memories

Think of an animal associated with forgetfulness. Chances are, the first thing that would come to mind is an animal that you might even have in your aquarium at home: the goldfish. This fish is so infamous for being bad at remembering things that "You have the memory span of a goldfish" has become an insult typically hurled at forgetful people. However, this piece of so-called common knowledge isn't actually accurate. Scientific findings over the past few decades don't even support this notion. In fact, considering its scatterbrained reputation, the role of the goldfish in memory research is rather ironic.

In an interview with the BBC, professor and fish behavior researcher Felicity Huntingford shared that, even in recent times, hundreds of studies have looked at goldfish learning and memory and did not find anything that would suggest that these popular pets have particularly bad memories. "Goldfish can perform all the kinds of learning that have been described for mammals and birds," she stated, adding that the goldfish's memory and learning ability are precisely why scientists have used it as a "model system" for various studies on memory formation and learning in animals.

In a 1994 study in the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, scientists gradually trained eight goldfish to use a lever that dispensed food, eventually limiting the feeding window to just one hour a day. They found that the goldfish actually remembered the feeding schedule, even after they disabled the food dispenser.

You swallow eight spiders a year in your sleep

The idea of something finding its way into your mouth as you sleep is, in itself, a terrifying prospect. Add spiders to the equation, though, and you might even start having trouble going to bed. It's an oft-repeated bit of trivia that the average sleeping person allegedly swallows a certain number of spiders (typically eight) every year. If it's any consolation, though, spiders are probably as wary of you as you are of them — and are highly unlikely to mistake someone's open mouth for a cave to explore.

According to Scientific American, the eight-legged critters that live inside your home wouldn't even think of going to your bed while you sleep, simply because there's no food for them to find there. They're also not particularly fond of humans, nor are they likely to feel curious enough to approach one that isn't moving. As professor Bill Shear, former president of the American Arachnological Society, puts it: "Spiders regard us much like they'd regard a big rock. We're so large that we're really just part of the landscape."

Plus, the vibrations that come from a sleeping person's heartbeat and snoring would be signs of danger to a spider and would probably make it hesitate to even approach your face. "Vibrations are a big slice of spiders' sensory universe," Rod Crawford, the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture's arachnid curator, explains (via Scientific American).

Bats are blind

The belief that most bats have very poor eyesight is a longstanding mistake that eventually birthed an idiomatic expression. Ironically, this couldn't be further from the truth: Not only do many bats see quite well, but some even have better vision than human beings.

According to Dr. Christopher S. Baird, an assistant professor of physics at West Texas A&M University, the fact that bats have advanced ears and can "see" in the dark via echolocation does not necessarily mean that they have poor eyesight. Their echolocation abilities come in handy at night, when food sources are harder to spot. However, most species are more than capable of finding food with their own eyes in broad daylight. A number of frugivorous bat species can even perceive and distinguish visual patterns, making it easier for them to spot fruits or sources of nectar.

While small bats (microbats) typically have smaller eyes, they're still able to spot food and other objects beyond the normal echolocation range (36 to 66 feet). On the other hand, large bats (megabats) possess larger peepers, which help them stay properly oriented when they're flying. Moreover, some of the larger bat species can see up to three times better than the average human being, per National Geographic. Interestingly, bats of all sizes take advantage of their eyesight, whether to protect themselves from approaching predators, travel safely, or even interact with one another.

The color red makes bulls mad

The image of a matador waving a red cloth (muleta) in front of an angry bull is so iconic that it has been featured in countless movies and television shows. Based on popular belief, the mere sight of the color red is enough to send any bull into a rage. This, of course, lines up perfectly with the idiomatic expression "seeing red." That's why it might be shocking to find out that, according to research, red fabric has just about as much potential to make a bull mad as a cloth of any other color — provided that it's being waved by the matador the right way.

As Science ABC explains, hooved animals such as bulls have dichromatic (two-color) vision, due to their retinal cells for color detection. Multiple experiments have shown that bulls get mad in front of a matador's moving muleta, regardless of its color. For instance, the popular show "Mythbusters" tried this in a 2007 episode. Using three dummies — one in red, one in white, and one in blue — the team demonstrated that bulls didn't focus on the red-clad dummy, but just charged right in.

It's the movement of the matador's cloth that drives the bull to aggression. Moreover, the bulls that are featured in bullfights are raised to attack at the drop of a hat. So why red? Perhaps it's to better hide the blood of the matador in case the bull manages to injure them.

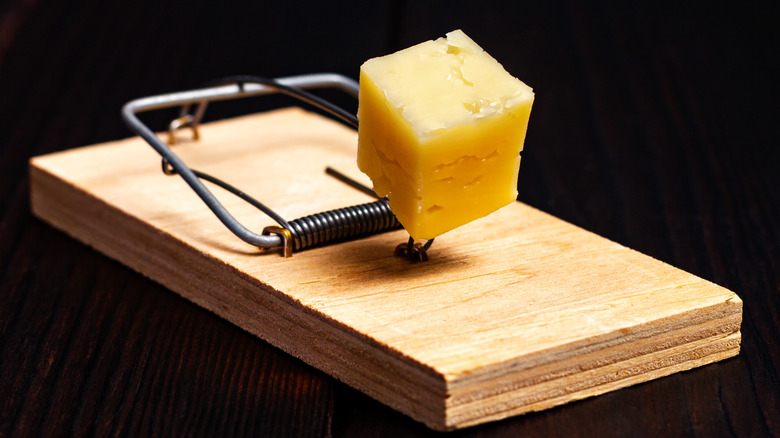

Mice love cheese

Think of any cartoon that features a mouse, and odds are that it would have a scene with the rodent either snacking on a slice of cheese or getting caught because of one. Indeed, pop culture portrayals have helped perpetuate the idea that mice specifically chase after such dairy products. However, there's a rather cheesy explanation regarding the strong association between mice and cheese — and it has little to do with the rodent's palate.

In an interview with Popular Science, urban rodentologist Robert Corrigan explains that mice aren't really picky about the food they grab. Rather, they're optimal foragers, meaning that their approach to obtaining grub is basically minimum effort, maximum gain. In other words, a mouse would be more likely to go after a high-calorie cup of mixed nuts than a relatively low-calorie slice of cheese, simply because the former provides more energy than the latter.

Experts believe that the myth about mice loving cheese may have started because, in the old days, people kept cheese in places around the house that were easily accessible to pests. In contrast, grains were kept in containers and meat was hung from high places. That said, if you really wanted to set an effective mousetrap, ditch the cheddar and go for something with lots of sugar, such as chocolates or fruits (via How Stuff Works).

Fossil fuels come from dinosaur fossils

It's not uncommon to see this rather interesting argument online: If plastic is made from fossil fuels and fossil fuels are made from dinosaurs, then plastic dinosaurs must be made from real dinosaurs. As hilarious and ironic as it may sound, that's actually not the case.

Because they're called "fossil fuels," a lot of folks think that oil comes from dinosaur fossils, despite the fact that the word "fossil" doesn't exclusively pertain to preserved dinosaur remains. In reality, fossil fuels are mostly the products of the decayed remains of prehistoric marine organisms (via the State Historical Society of North Dakota). Fossil fuels form when the organisms' remains (also called kerogen) get buried underground. Over millions of years, they're subjected to various geologic pressures and processes and undergo chemical changes to become hydrocarbons, the building blocks of gas and crude oil.

So how did the "fossil fuels come from dinosaurs" myth start in the first place? According to Powells, the Sinclair Oil Corporation came up with the idea of using a long-necked dinosaur as a mascot in their promotional materials way back in 1930. The connection between dinosaur fossils and fossil fuels was likely reinforced three years later, when the company commissioned a set of gigantic dinosaur statues and put them on display at the Century of Progress World's Fair in Chicago.

Humans evolved from monkeys

Up until now — and despite the abundance of evidence supporting the idea — the theory of human evolution remains an incredibly divisive topic for discussion. Oftentimes, one side would present the facts and studies that back it, while the other would cite their personal beliefs and outright reject it. Some even claim that it's just not possible that humans evolved because monkeys are still around; if Homo sapiens really did branch out from simian roots, then why haven't the monkeys all disappeared? The answer, while straightforward, isn't really that simple: Humans didn't evolve from monkeys but do share a common ancestor with them.

According to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, the similarities in genetics and physical appearance between modern-day humans and great apes such as gorillas and orangutans suggest that at least 6 million years ago, apes and humans went on separate evolutionary paths from a single progenitor. In fact, almost 99% of the human genetic sequence is the same as that of bonobos and chimpanzees (via National Geographic).

This is also the reason why there is no such thing as a "missing link" between humans and apes: There can't be a missing link, because one family didn't turn into another.

Chameleons change colors for camouflage

If Culture Club's uber-popular song was to be believed, chameleons have a habit of coming and going as they please. Unsurprisingly, this might have helped reinforce the belief that these small reptiles use their color-changing abilities to blend in with their surroundings and render themselves invisible at will.

However, this has turned out to be a misunderstanding of how this unique chameleon ability actually works: they change colors not to camouflage themselves, but to make themselves more prominent and noticeable (via How Stuff Works). As the Oakland Zoo's Daniel Flynn explains, "The color changing properties of chameleons don't really help them blend in, but rather their natural, relaxed state is what helps them blend in."

A chameleon's color-changing "magic" only really begins when they experience intense emotions, such as excitement or agitation. The chameleon's iridophores — the crystalline cells under its skin — undergo structural changes (either by compressing or separating), refracting different colors of light in the process. In a 2015 study published in Nature Communications, researchers found that a chameleon's iridophores function like "tiny mirrors" and have the ability to "absorb or reflect any and all colors of the spectrum" (via How Stuff Works).

Owls can turn their heads 360 degrees

Owls are magnificent creatures with one admittedly freaky ability: they can turn their heads in either direction, to a degree that would otherwise snap a human being's neck. According to Backyard Chirper, it's easy to mistake this as the owl "turning its head in a complete circle," based on the angle from which you're looking at the bird.

As impressive (and somewhat creepy) as it may be, however, the owl's ability to turn its head does still have its limits: 270 degrees, to be precise. And that's only because its eyes are also restricted from movement to begin with. Unlike the eyes of human beings, owl eyeballs can't rotate because their eye sockets are fixed. In other words, if they want to look for potential prey or approaching threats within their general area, they must turn their heads and stretch their necks accordingly (via National Geographic). The owl owes its remarkable flexibility to the fact that only one socket pivot connects its head. Meanwhile, because human beings have two socket pivots, the ability to turn one's head is largely restricted. Additionally, owls can safely twist their heads due to the multiple vertebrae in their necks and spines.

Still, the particulars of how an owl can survive such a neck-twisting remained largely unknown. That is, until 2013, when a team of researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine collected data from dead owls and discovered unique arteries that allow them to turn their heads nearly 360 degrees without harming themselves (via Science Daily).

Dogs and cats are colorblind

Yet another common misconception is the range of colors that cats and dogs can see. According to the American Kennel Club, for a long period of time, many canine experts believed that dogs could only see black and white. However, thanks to newer research, scientists know that even though dogs don't see the world in the same way as humans, they can still perceive some colors.

Like bulls, dogs are dichromats, meaning their eyes have only two varieties of color-sensing cells, enabling them to see only violet and yellow-green instead of the primary colors (via the McGill Office for Science and Society). Interestingly, this means that their eyes are actually more sensitive to blue and purple wavelengths than humans' eyes are (though humans have the edge when it comes to detecting red, yellow, and green). Meanwhile, cats may actually have a third color-sensing cell in their eyes, though some studies contradict this. Either way, the prevailing scientific idea is that felines may be capable of seeing the same colors humans do, albeit in a different degree of saturation.

Without a doubt, though, these popular pets are better at hunting than humans, due to the way their eyes have evolved across thousands of years. Dogs and cats are not only adept at seeing moving targets, but they're also said to be exceptional at spotting things under low-light conditions. Moreover, they both possess wider visual fields compared to human beings.

Ostriches hide their heads in the sand

It's an undeniably cartoonish sight: a gigantic, flightless bird with a long neck, desperately trying to dig a hole in the sand to hide its head in. As it turns out, this ridiculous — and certainly inaccurate – depiction of ostriches likely originated from a misinterpretation of one of its signature defensive moves.

As National Geographic explains, ostriches attempt to make themselves less conspicuous when they sense danger nearby. By pressing their long necks to the ground and sticking as close to the soil as possible, they become harder to spot, especially since the color of their plumage allows them to blend in better.

All things considered, though, a bird as large and well-equipped as the ostrich shouldn't have much of a reason to fear for its life. After all, it holds the record for the world's largest bird and weighs as much as two adult men (via National Geographic Kids). Plus, it has extremely powerful legs and feet with sharp claws that can kill any approaching predators — whether it's a lion, a leopard, or a human — with a single kick.