Why WWII's Fu-Go Balloon Bombs Are Still Dangerous Today

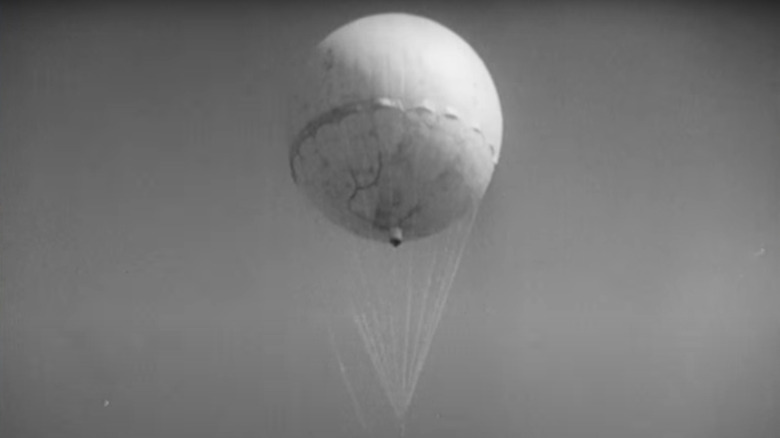

Massive balloons floating across the West Coast in the 1940s (like the one above) may have looked like giant, mesmerizing jellyfish in the sky, but in reality the Japanese meant them to be deadly mechanisms designed to kill Americans during World War II. In many ways, the plan was as simple as it was diabolical. The Japanese figured out a way to harness the eastward jet stream over the Pacific Ocean and used balloon bombs — named fu-go — to launch silent and deadly devices. Their target: American cities, farms, and forests. The plan "called for sending bomb-carrying balloons from Japan to set fire to the vast forests of America, in particular those of the Pacific Northwest. It was hoped that the fires would create havoc, dampen American morale and disrupt the U.S. war effort," historian James M. Powles wrote in the journal World War II [via Smithsonian].

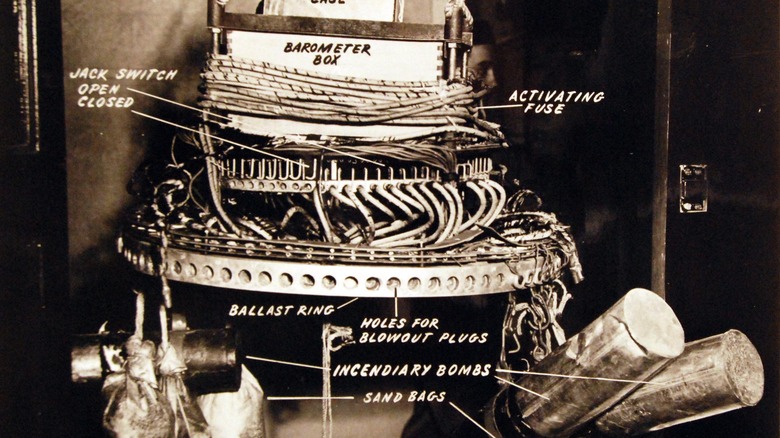

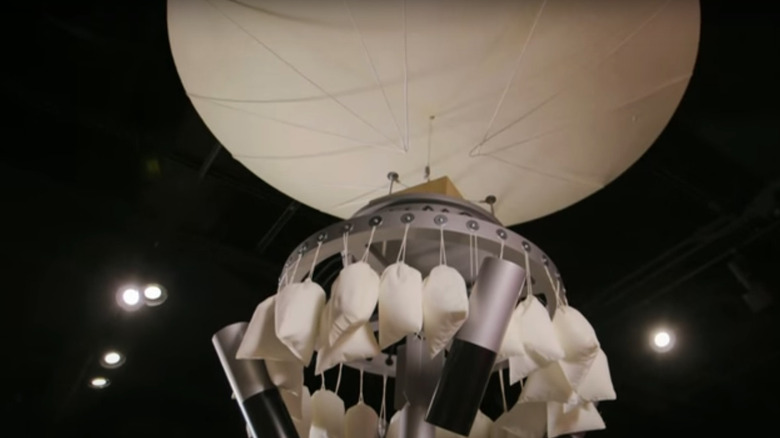

The Imperial Japanese Army designed the fu-go balloons, which were made of lightweight paper from the bark of trees. The Japanese navy was the primary launcher of the balloon bombs, which were equipped with sensors, triggering devices, and powder-packed tubes, among other mechanisms. "The envelopes are really amazing, made of hundreds of pieces of traditional hand-made paper glued together with glue made from a tuber," Marilee Schmit Nason of the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Museum in New Mexico told NPR. "The control frame really is a piece of art."

Children helped make fu-go bombs

Japan didn't make just a few of those fu-go balloon bombs; they launched more than 9,000 of them across the ocean. According to WNYC's Radiolab podcast, hundreds — perhaps thousands — of school children were enlisted to help make the special paper fashioned out of mulberry wood, called washi. Schoolgirls worked 12-hour days making tens of thousands of the sheets, gluing them together to make panels of the balloons. By the time the balloon bombs were assembled, they "were 33 feet in diameter and could lift approximately 1,000 pounds, but the deadly portion of their cargo was a 33-lb anti-personnel fragmentation bomb, attached to a 64–foot-long fuse that was intended to burn for 82 minutes before detonating," according to a presentation by Missouri University geological engineer J. David Rogers.

The fu-go balloon bombs were seen in the air (and on the ground) from Alaska to Mexico, and as far east as Michigan. However, the airtime from Japan to the U.S. was several days and the overwhelming majority of them were believed to be lost in the ocean. Per Powles (via NPR), many accounts in the western part of the U.S. sounded similar; people saw what they thought were parachutes that had lighted flares and a whistling sound before seeing and hearing an explosion. To date, only one known explosion caused fatalities — six deaths in Oregon — before the Japanese pulled the plug on the fu-go project, which only lasted from November 3, 1944 until April 1945.

The fu-go balloon bombs were a secret but still deadly

Through it all, the fu-go balloon bombs largely remained a secret kept from the American public, according to the Detroit Free Press. One December 18, 1944 Associated Press story mentioned the military and the FBI conducting investigations into balloons that had been found. Newsweek ran a story titled "Balloon Mystery." Soon after, the War Department's (the precursor to the Pentagon) Office of Censorship asked newspapers and radio stations to not mention any of the incidents, saying they did not want to encourage Japan or create panic among citizens. The press complied.

Although World War II ended more than 75 years ago, the fu-go balloon bombs can still be dangerous. Comparatively speaking, very few of the balloons have been found. Yet, each decade since World War II ended, several have been discovered across North America. Most recently, in 2019, a Canadian hunter in British Columbia found a balloon bomb and evidence that it had started a small fire, according to the Rocky Mountain Goat. Bowdrie Widdell, the hunter who found the fu-go, said he would have liked it to have been preserved but realized it likely would have found the same fate as other discoveries — detonated under a controlled environment for the safety of others.