The Arsenic Dress And Other Clothing That Killed People

You may have heard, at one time or another, that "fashion hurts." Perhaps this was uttered while you were struggling to get into a pair of too-tight jeans or wearing a trendy but itchy dress. Or maybe it was a pair of high heels. After all, Christian Louboutin, the shoe designer responsible for those sky-high heels with iconic red soles, acknowledges that "high heels are pleasure with pain," though it should be noted that Mr. Louboutin doesn't wear the heels himself, according to Independent.ie.

Whether or not you accept that looking good means being occasionally uncomfortable or even in brief pain, surely we can agree that being in danger has no place in the world of fashion. Yet, throughout history, there are instances where clothing has become such an issue that it's taken lives.

Sometimes, it's poor regulations, as when the Victorians went gaga for a bright green dye that was also loaded with arsenic. In other times, it's been atrocious working conditions for garment workers. On occasion, fashion fads and indulgences have directly or secondarily led to a person's demise, too. These are the tales of clothing throughout history that have killed people.

Green dresses with a serious dose of arsenic

The Victorians had quite a complicated relationship with arsenic. For one, they knew it was deadly, according to Jezebel. Britain even passed two different bills that restricted how much arsenic an individual could obtain. But, in a key oversight, that legislation didn't account for industrial use. People who made artificial flowers, for instance, were at risk of taking in arsenic-laced powder used to pigment the fake leaves. In 1861, flower maker Matilda Scheurer even died a painful death after ingesting too much of the stuff over the course of her short career.

The Paris Review reports that it all really started in 1775, when chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele mixed sodium carbonate, arsenious oxide, and copper sulfate. The solution produced a bright green dye, eventually known as "Scheele's green," that many Victorians simply couldn't resist.

Perhaps they should have practiced more self-control. Wearers of the dye could suffer, too. They could gaze in horror upon skin ulcerations or wonder if they were poisoning fellow partygoers. One London doctor, George Rees, tested a sample of green cotton and found that it was loaded with Scheele's green (via "The Arsenic Century"). What's worse, the dye was so loosely applied that it could easily be shaken out while a wearer was dancing or making small talk.

Starched collars

Collars may seem pretty innocuous, but for some men of the 19th century, they were death traps. But it all started as a convenience. According to Brooks Brothers, the detachable collar was invented by New York housewife Hannah Lord Montague in 1825. Sick of laundering her husband's shirts just when the collar got dirty, she realized that she could simply create a separate collar that kept her husband looking tidy while sparing her extra washing.

Ultimately, highly starched collars became all the rage. According to the BBC, the starching got so serious that the collars were occasionally referred to as "Vatermörder" or "father killers." The reason? If a man were to become unconscious — perhaps by having one brandy too many — then he might slump forward. The overly stiff collar could then cut off his airway and blood supply.

It might sound far fetched, but it apparently did happen on occasion. In 1888, the New York Times reported that one John Cruetzi was found dead in a city park, having apparently gotten drunk, then passed out on a bench. When his head fell forward, his fashionable collar cut off his breathing. A 1900 edition of Daily Mail and Empire reported that another unfortunate victim was found in his bed still wearing his collar. The cause of death was determined to be a collar so tight that it choked him and caused bleeding in his brain.

Crinolines

At certain points in history, big skirts were all the rage. Yes, of course, people took time out of their day to make fun of fashionistas, as humans have surely been doing for all of history. But you must admit that a woman making her entrance into a room with a dramatic swath of skirt has a certain romantic appeal. That is, until she catches on fire. Or her skirt knocks her off a pier. Or perhaps it catches her and her companions beneath the wheels of a passing carriage.

Such were the reported dangers of crinolines in the Victorian era. These large skirts, typically supported by a series of connected hoops, were so popular that the trend was eventually deemed "crinolinemania," according to The Vintage News. The cage crinoline, made with lightweight and flexible steel hoops, was actually welcomed by women who had previously struggled with many layers of cumbersome petticoats for a similar effect.

Those light skirts allowed for increased air circulation, which may have been comfortable but also contributed to some deadly fires. "Fashion Victims" notes that there were quite a few people struck by the potentially deadly combination of fire and crinoline, including Fanny Longfellow, wife of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and two of Oscar Wilde's half-sisters. That wasn't all. "Corset and Codpieces" notes that one man was pushed into the path of carriage by a sidewalk-hogging crinoline, later dying of his injuries.

Viscose

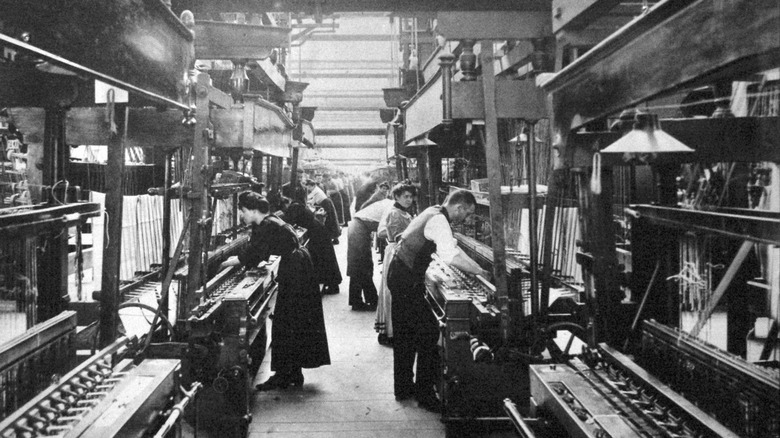

Silk is expensive. Yet, in the early decades of the 20th century, advancements in chemistry made it possible for people to enjoy all the luxury of silk without the luxe price point. At least, that's how it seemed for a while. For the people manufacturing this fabric, the price of fashion may have been too high.

The fabric in question was viscose, a subtype of rayon, which is itself a synthetic material that must be made in a factory-type setting. According to the CBC, it was initially hailed as a wonder product, given its many applications. But workers who created the stuff were exposed to carbon disulfide. This toxic substance was so injurious to people's health that it produced significant mental health disturbances, to the point where some workers had to be physically restrained from jumping out of second-story windows after exposure warped their minds.

Even if someone could detox from the carbon disulfide, they weren't necessarily in the clear. Collectors Weekly notes that even the seemingly lucky survivors were more likely to develop Parkinson's disease later in life. Meanwhile, the people who wore viscose or rayon clothing experienced no known side effects at all.

High heels

If you've ever worn heels out for a night on the town, then you know that these fashionable shoes can sometimes present a bit of a gamble. The higher the heel (and, let's admit, the more you order at the bar), the more likely you are to take a nasty tumble thanks to this impractical footwear. But could it really kill you?

Perhaps. At least, that's what happened to a 19th- and 20th-century socialite known as Jennie Jerome. Or, as Encyclopedia.com notes, that was her name before marriage. In 1874, she married Lord Randolph Churchill, becoming Lady Churchill. Yes, those Churchills. As it turns out, Jennie would become the mother of future U.K. prime minister Sir Winston Churchill.

Jennie had a pretty dramatic life, serving as a nurse during wartime, acting as a writer and editor, and navigating the intense and sometimes cutthroat world of British high society. But it all came to an end in June 1921, when the 67-year-old Jennie was rushing down the stairs at a friend's manor. Her high-heeled shoes caused her to slip and break an ankle. Even worse, the fracture became infected, to the point where her leg was amputated. But that still wasn't enough, as that leg's artery eventually began to hemorrhage, and she died later that month.

The fontage

The genesis of the fontage hairstyle seems a bit naughty, but surely no one thought that it would lead to fiery death. According to Collectors Weekly, it was originally an affectation of French king Louis XIV. As the story goes, he was so charmed by a mistress' impromptu decision to wear her hair piled on top of her head that the look quickly spread at court. Though the original innovator, the Duchesse de Fontages, came up with the idea after falling off a horse and needing a quick fix for a ruined hairstyle, the resulting trend soon got pretty complicated. Women began teasing their hair into large poufs, accessorizing with fabric, flowers, and props.

Alas, all those accessories tended to be pretty flammable. One woman reportedly sported a fontage so large that it connected with a candlelit chandelier. Her hair quickly went up in flames and she unfortunately died of her injuries.

Don't blame the French alone for suffering from this affectation. Numerous English newspapers from the 18th century claim to tell similar tales (via All Things Georgian). One woman's elaborate hairstyle caught on fire when she bent down too close to a fireplace; she subsequently died. Others survived but were surely scarred by close brushes between their towering hair and ever present candles, as well as one case where the pins in one woman's hair supposedly attracted lightning straight to her flammable head.

Long skirts

Skirt length has seemingly been a never-ending topic of discussion for a variety of folks, whether it's old cranks complaining or fashionable folk debating. Yet, there was once a time where skirts were considered too long, and not just because it wasn't on-trend. Rather, it could well have been that trailing skirts were bringing death and disease right into the home.

During Victorian times, more and more people began to accept that germ theory was a thing. Yet, cities were still catching up to the sanitation business, meaning that streets across the globe may have looked like a potential petri dish to some. What may have made them cringe more than usual was the sight of a woman with long skirts dragging through all of that diseased muck, then returning home to her unknowing family.

As Hyperallergic notes, by 1900, many believed that deadly diseases like influenza or typhus could be brought into the home via these skirts. Some women even reportedly resorted to devices meant to hitch up their skirts while they walked about. To be fair to fashionistas, it wasn't just ladies who might be bringing in this disease. "Fashion Victims" notes that garments made in many contexts, from bespoke to ready-made, could bear disease-carrying bugs if the workshop it came from was contaminated.

Sheer dresses

If you look through some unscrupulous sources, you may hear of something known as "wet muslin disease." It's related to the late 18th- and early 19th-century trend of wearing light, often sheer muslin dresses that were meant to mimic classical styles of ancient Greece and Rome. According to Sexuality in Fashion, stories soon sprung up of daring French trendsetters who purposefully dampened their dresses so the fabric would cling to their bodies. Of course, those silly people caught cold and died. Yet, there's no real evidence of anyone doing a historic version of a wet t-shirt contest, hinting more at the reaction of pearl-clutching fuddy-duddies than reality.

While wet muslin disease may be a myth, sheer dresses could still allow some people to get seriously ill. According to "Crossings in Text and Textile," contemporary writers discussed women who wore these gossamer dresses even in the dead of winter. An 1803 Parisian epidemic of influenza — which could easily kill you in an era before antibiotics and handwashing — was even linked to this trend, to the point where it was popularly known as "muslin disease" (via "The White Plague").

Sandblasting

Lest you think that Regency and Victorian people had a lock on deadly trends, take a look to the 1990s and 2000s. If you were of an age during that time, you may have sported a pair of fashionably sand-blasted jeans. But you may not have known that those jeans, now often sitting in landfills or discarded in some dark corner of a forgotten closet, came with a deadly cost.

That's because sandblasting can seriously affect workers with a disease known as silicosis. According to the BBC, this process requires an air compressor, a hose, and sand. This means that fine silica dust often floats around workers. Without protective equipment, which can be in short supply in poorly regulated factories, workers inhale the silica dust. After a while, they suffer irreversible effects like shortness of breath, weakness, and persistent coughing. Some become permanently disabled. In the worst cases, silicosis can be fatal.

It's been a documented problem in places like Bangladesh, Turkey (via Daily Sabah), and China, where Al Jazeera uncovered poorly ventilated workspaces producing jeans for brands like American Eagle and Hollister.

Mourning fashion

For well-to-do people during the Victorian era, when fashion got extreme and regulations seemed to be erratic or even downright nonexistent, mourning wasn't just a time for grief. It was also a time for fashion. Women especially were expected to follow a restrictive set of customs. At the height of this trend, Racked reports, widows were expected to spend a full year in "deep mourning," wearing all-black dresses made out of a dull fabric and, when she dared to venture outside, a veil covering her face. After a year, it was socially acceptable for her to lighten things up a bit in the "second mourning" and "half mourning" stages, which implemented a bit of color — but, of course, not too much, lest a woman enjoy herself (via The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Ironically enough, all that black fabric could be deadly. According to Racked, early synthetic black dyes employed benzene, arsenic, chromium, and other toxic chemicals. Wearers sometimes suffered skin irritation and damage to their respiratory system. And, as some doctors argued, wearing too much of this fabric could potentially lead to one's own death, along with "bad complexions, bad eyes, bad digestion and bad temper."

Ballet fashion

Ballet dancers today have to deal with some serious bodily consequences for their art, from pressures to maintain a certain weight, as per The Guardian, to the toe-crushing forces demanded by pointe shoes (via Healthline). But you probably won't have a modern ballerina going up in flames.

Unfortunately, dance trends of the past meant that this was once a reality, due to 19th-century trends for gossamer skirts and stages lit by oil lamps and candlelight. According to Racked, these flowy fabrics encouraged the free circulation of air and, if flames got too close, also the rapid growth of fire.

That's what happened to ballet superstar Clara Webster, who died in 1844 after an oil lamp touched her outfit. Other dancers, dressed in similar clothes, stayed away for their own safety, according to the Victoria and Albert Museum. In 1862, ballerina Emma Livry died of blood poisoning over an agonizing eight months, all after her skirts caught fire on stage (via Racked). She could have worn a costume that had been chemically treated with fire-retardant, but the compound made skirts yellowish and overly crisp. Given that dancers made or broke their careers on such aesthetic decisions, it's not surprising that Livry declined the treated skirts.

Hobble skirts

Though it was a relatively brief fashion trend, the hobble skirt proved to be a serious hindrance to many women. According to Encyclopedia.com, the height of this fashion came between 1905 and 1910, when the long, restrictive skirts were so tight at the bottom that they impeded a wearer's gait to a characteristic hobble. For many, it was surely an annoyance when they wanted to keep up with a group or make their way from one room to another. But for an unfortunate few, the trend proved deadly.

One incident occurred at a race course near Paris in 1910, when a horse bolted through a crowd. Most people got away, reports "Fashion Victims," but one woman was so restricted by her skirt that she remained in the animal's path. She fell beneath the horse and, with her hair caught in its shoes, was dragged along for some period of time. The woman eventually died of a skull fracture.

In 1911, the Adelaide, Australia, newspaper The Advertiser reported that two women had died in a boating accident in a Russian resort. The reporter rather harshly blamed their drowning on the "imbecile dress" that hobbled them at the knees, despite an apparent reputation as good swimmers in other outfits.

Scarves and neckties

Lest you feel smug for being a modern person, living in a world that's mostly free of arsenic-laced dresses and typhus-laden coats, why don't you go and take a look in your own closet? Perhaps you've got some ready-made strangulation hazards waiting there for you, whether it's a fashionable scarf or that necktie that you wore to a couple of weddings or that one stuffy work meeting with the CEO.

These may seem like innocuous accessories, but try asking someone like dancer Isadora Duncan. Only, you can't, because Duncan died in a 1927 car accident when the long, trailing scarf became entangled around the open axle of a car, according to History. When the auto began rolling, she was violently pulled from the car by her neck, dying in seconds.

Neckties can be deadly, too. The New York Times reported on the 1934 death of one company manager when his cravat was caught in a machine. In 2001, a New Zealand man suffered a similar fate when his more modern necktie was caught up in a sanding machine, according to the NZ Herald.