How Exactly Does The Immune System Work?

A sneeze, a cough, a sniffle, an itchy eye: These are symptoms we've all experienced countless times. Sometimes, viruses and bacteria gain the upper hand and we get a fever that roasts ourselves clean of interlopers. Sometimes, an army of microorganisms creations conditions and illnesses that win out. All day, every day, our body and its 37 trillion cells (per National Geographic) cooperate to keep us alive, while every second one million cells per person die (per the Karolinska Institutet). The body is caught in a cycle of incessant cellular death and regeneration. Neurons last a lifetime, but white blood cells only 13 days (per Healthline). And for the record, you are composed of more bacterial cells (38 trillion) than human cells.

And yet, with so much complexity, and the capability for so much to go wrong, very little typically does. We have our immune system to thank for this. The body is composed of 200 types of cells, including blood cells (red, white, and platelets), 86 billion neurons, 50 billion fat cells, and 2 billion heart muscle cells. The most plentiful type of cell, red blood cells, accounts for over 80% of all the body's cells. This makes sense, because the blood is not only what transports chemicals throughout our body, but comprises the main stage of our immunological, cell-on-cell battleground.

A network of organs, cells, membranes, and more

The first point about the immune system comes from its second word: system. As the Immune Deficiency Foundation explains, the immune system is a decentralized collection of organs and cells spread throughout the whole body, not just in one spot like the brain. Some of its major organs include the thymus, liver, spleen, and lymph node clusters (under the armpits, in the hips, and elsewhere).

The immune system's cells start as stem cells in bone marrow, travel through the body using our circulatory system, and communicate with each other in lymph nodes. The system's defenses start with the skin, an outer shield that collects loads of bacteria. As MedlinePlus says, mucous membranes play a big role, too, because like skin they can trap bacteria and other threats. They're inside, lining organs and occupying body cavities.

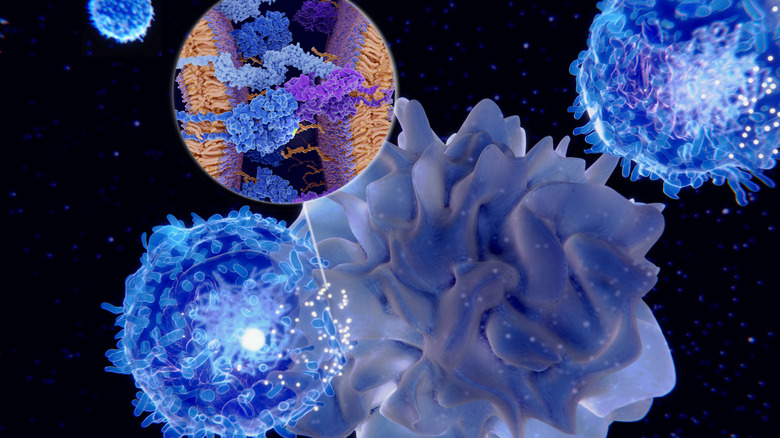

In the end, all immune system responses boil down to cell-on-cell combat (like the picture above). When the immune system is triggered, cells of various types are dispatched to deal with the threat (antigen). Lymphocytes are an important cell type that confronts foreign bacteria or viruses. When they meet an enemy, they mutate into plasma cells specific to the threat, and release antibodies (proteins) to attack. If the threat is on file, so to speak — meaning you've encountered it before — then you can more easily fight off the illness. This is what vaccines do: They give your body a record of an intruder.

Innate, active, and passive immunities

Doctors define a person's defenses (immunity) in three ways: innate, adaptive, and passive immunities, as sites like Medical News Today and Medline Plus explain.

Innate immunity is just that: It's the built-in barriers you've got on a macro level — skin, mucous membranes, hairs in your nose and ears — that block bacteria or collect them for easy destruction (like with soap).

Passive immunity is what the body doesn't have to learn, but knows how to defend itself against from birth. Passive immunity is also referred to as "borrowed" immunity, and is kind of like a short-term shield for newborns. Typically, this is the kind of immunity that babies inherit from their mothers through the placenta or breast milk, which helps them survive very vulnerable early years when their own immune systems are still learning how to fend off attacks. As a person passes from childhood into adulthood, their immunity strengthens; children are the most vulnerable, as the Immune Deficiency Foundation says.

Adaptive immunity, also known as acquired immunity, is everything that your own, single body has learned to fight off. The folk belief that children need to play outside to "build up their immunity" is no joke. As a child or adult is exposed to antigens (within reason), the body develops a super-long compendium of diseases that it knows how to deal with. This is exactly like a library, where more books equals a more adept immune response. Only one exposure often means lifelong protection.

Antigens vs. antibodies

Foreign bodily invaders are called "antigens." In the end, they come in two varieties: bacteria and virus. Both are single-celled organisms, but they're characterized by a somewhat disturbing difference, as the University of Queensland explains. Bacteria are fully alive and autonomous, and can live on either surfaces or inside multicellular creatures like humans. Viruses, however, are technically not alive, which is really disturbing if you think about it. They require a host to replicate, like any parasite, and cannot otherwise make copies of themselves. They're basically complex chemical formations.

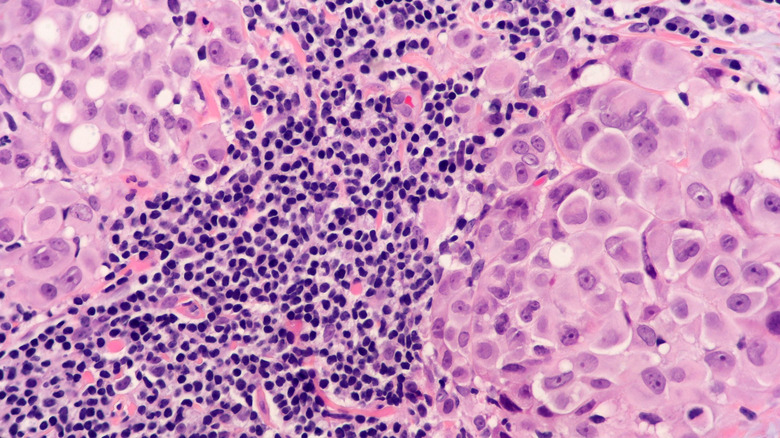

Depending on the antigen, the body will take a different defensive tactic. If bacteria make it past the body's innate immune system, for instance, white blood cells (leukocytes) can just outright engulf them. Neutrophils take up this task, making up 55-70% of all white blood cells, as Healthline states. Viruses are more tricky to deal with. As the Immune Deficiency Foundation says, viruses can multiply inside of cells, where they essentially "hide" from our immune system. Otherwise, when they initially infect a cell, that cell sends out an alert for other cells to congregate and release their antibodies to overwhelm the virus.

This is where nutrition comes into play. It is literally, physically the case that your cells are constructed from the materials you ingest. Without the proper assemblage of nutrients, kind of like Legos, your body can't build all the cool stuff it needs in order to keep you safe from microscopic invaders.

Immunodeficiencies

No primer on the human immune system would be complete without talking about immunodeficiencies: conditions that weaken the immune system and lead to people getting sick. The immune system is complex enough — and we've barely scratched the surface — without any additional stressors mucking it up.

As the Immune Deficiency Foundation explains, there are two types of immunodeficiencies: primary and secondary. Secondary immune deficiencies are easier to talk about. They're weaknesses caused by something else other than the immune system, and include poor nutrition, aging, certain medications that cause specific side effects, and infections like HIV which make it more difficult for the immune system to fight off other diseases.

Primary immune deficiencies, by contrast, are caused by the immune system itself. These include genetic conditions or defects of the immune system which weaken or even cripple its ability to function. There are over 400 disorders classified as primary immunodeficiency diseases. Some are rare; some are relatively common. Some are inherited, like X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA) or Severe Combined Immune Deficiency (SCID); some are not, and some spring from inherent vulnerabilities exacerbated by one's environment.

As you could imagine, treatment of primary immune deficiencies is super-tough, and usually consists of just trying to not get sick to begin with. Secondary immune deficiencies can be treated with a variety of methods, ranging from simple medication all the way to organ transplants. In the end, there's one key lesson to all this: Take care of yourself.