The Mysterious Death Of Pope John Paul I

Catholics and non-Catholics alike respect and admire Pope John Paul II for his dedication towards human rights and anticommunism (via NBC) around the globe. But most have never heard of his namesake and predecessor, John Paul I. This is because, according to Britannica, John Paul I died after a 33-day papacy in 1978, the shortest in modern Catholic history. Those who are familiar with him, however, know him as the victim of an insidious murder plot.

No one knows for certain how the pope died. But Traditionalist and progressive skeptics alike have formulated their own theories regarding the pope's sudden and unexpected death. The theories all have one thing in common, however. The pope was killed to prevent the discovery of the seedy underbelly of the government of the Holy See, a theory that has gained evidence and support in recent years. Here is the story of how the "smiling pope" may have fallen victim to the 20th century's greatest – and perhaps most Byzantine – conspiracy.

The winds of change

To understand the theories regarding the death of John Paul I, it is necessary to understand the 20th-century history of the Catholic Church. John Paul I became pope on August 26, 1978, following a turbulent period in the Catholic Church's history. The controversial and misunderstood Second Vatican Council (aka Vatican II) brought a slew of changes to the Catholic Church. The most significant was the replacement of the Latin Tridentine Mass with the current vernacular Ordinary Form (Novus Ordo in Latin) in 1970, a major sticking point between Traditionalists and their opponents.

Cathleen Kaveny, writing in Commonweal Magazine, notes that critics called the decade following Vatican II the Church's "silly season," as strict catechism and solemn masses were traded in favor of "sharing, caring, and constructing felt banners." But there was hardly anything silly about it. Catholicism suffered acrimonious splits with Archbishop Marcel LeFebvre's Traditionalist faction SSPX in 1970 (via EWTN) and another with the sedevacantists, who consider post-Vatican II popes to be fake. But the death of Pope Paul VI in 1978 opened the possibility to elect someone open to reversing parts of Vatican II. Thus, John Paul I came to the papal chair in an atmosphere of instability inside the Vatican as he sought to navigate the minefield between Traditionalists, who wanted to restore the pre-'62 church, and progressives (aka supporters of female priests, birth control, etc.) who felt that Vatican II had not gone far enough.

Vatican, Inc.

In addition to the problems surrounding Vatican II, Pope John Paul I faced another issue that dated back to Italy's final unification in 1870. According to NPR, Italy, buoyed by anti-clerical sentiment, conquered the Papal States and confiscated the papacy's lands and properties in Central Italy, including the city of Rome. In response, Pope Pius IX excommunicated the Italian government and, according to author David Kertzer, declared himself "a prisoner in his own palace" — the Vatican, his only remaining sovereign territory.

The situation changed in 1929 when the newly-minted state of Vatican City and Italy signed the Lateran Treaty (pictured above). The Vatican was compensated for the territorial and property losses incurred in the 1860's and obtained exemptions from Italian taxes. The new state could invest duty-free in property, stocks, and other financial instruments outside its borders through the Institute for the Works of Religion (aka the Vatican Bank). Although the provision kept Italy out of Vatican affairs, it allowed unscrupulous Vatican officials to partake in shady financial dealings because the Vatican, as a sovereign state, could not be audited (via Time Magazine). Shady dealing proliferated in the 1970s, and by 1978, it risked blowing up into a major public scandal just as a papal election was about to take place.

The August Conclave of 1978

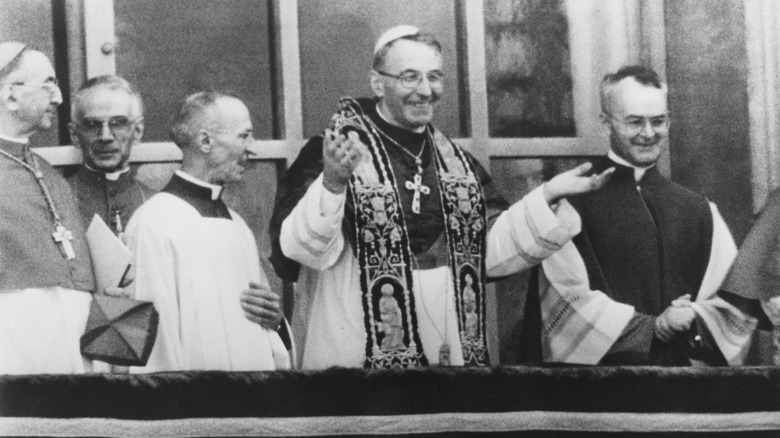

1978 was a special year in that there were two conclaves. The more famous one elected Cardinal Karol Wojtyla as Pope John Paul II. But the one of interest to this article was the August Conclave of 1978. According to the Washington Post, this conclave was a breeze. The College of Cardinals quickly elected a political outsider to Vatican politics: Albino Luciani, the patriarch of Venice.

Luciani styled himself Pope John Paul I in honor of his two predecessors. His niece Lina Petri (via Catholic Review) gives some insight into his agenda that never materialized. The new pope's goal was not a "progressive update" to the church that would have allowed birth control and female priests. He sought to frame Catholic teachings in simple, everyday language accessible to all. Because of his warmth, he became known as the "smiling pope" and wasted no time in building that image. According to Time, he dispensed with the papal coronation, opting for a solemn mass that made him seem more like an ordinary person rather than a monarch.

Although he seemed like the perfect candidate to lead the Catholic Church post-Vatican II, EWTN series Papal Artifacts notes that the new pope was considered a political "lightweight" due to his lack of experience in papal government. In an interview with UPI, crime author David Yallop suggested that this choice was deliberate. His lack of experience with Vatican intrigue made him pliable by the Vatican's less scrupulous factions. Regardless, he never had a chance to do much. 33 days later, he was dead.

The official narrative

As with all mysterious or unexpected deaths, there is always an official narrative that inspires the naysayers. The official account rests on the statements of the pope's Irish secretary, Fr. John Magee, and Venetian priest Fr. Diego Lorenzi, two of the last people to see him alive. According to Italian journalist Stefania Falasca's book "The September Pope," John Paul I took care of some evening state business before going to bed, including a phone call with Vatican Cardinal secretary of state Jean Villot regarding his successor as patriarch of Venice.

According to Fr. Lorenzini, both priests were present at dinner when the pope complained about chest pains. Fr. Magee allegedly told the pope that the doctor was on call if he needed it, but the pope refused and went on with his business. During a 9 p.m. phone call with the Archbishop of Milan, the Milanese secretary did not notice anything wrong with the pope over the phone. Fr. Lorenzi left at that point, a fact confirmed by the nuns who were present at dinner. Sr. Margherita Marin, a key witness in the story, said that the pope returned to the papal apartments (pictured above) at 10:30. The next morning, according to the Irish Times, Fr. Magee expected the pope to be in his private chapel saying his morning prayers. When he did not find him there, he went to the papal apartments, where he found the pope dead in his bed. This account mirrored the official Vatican statement delivered on September 29, 1978. But this was, as the Irish Times notes, a "white lie" at the very least.

Inconsistencies emerge

In 1987, the Irish Times challenged Fr. Magee's narrative. Fr. Magee responded that "[he] found him and [he] will stand before any person and challenge him." But in 1988, he changed his story. It turned out that a nun named Sr. Vincenza Taffarel had discovered the dead pope first.

According to "The September Pope," Sr. Margherita Marin rose at 5 a.m. to pray and receive a grocery delivery. Her fellow nun Sr. Vincenza left the pope's morning coffee in the sacristy around 5:10 for him to drink before prayer. Sr. Margherita noticed it was still there 15 minutes later. It was not normal for the industrious John Paul I to sleep in. Thinking it a joke from the "smiling pope," the nuns went to check on him. They found him stone-cold dead in bed with darkened fingernails. But nothing else was out of place. The Vatican doctor concluded the pope had died of heart failure.

Thus, it turned out that Fr. Magee's claim was, at minimum, misleading. He covered for himself claiming that "[he] did find the body of his holiness. [He] just didn't find it first" (via Irish Times). Sr. Vincenza had called him around 5:30 a.m. to inform him of her discovery. So why the "white lie"? The Irish Times notes that Fr. Magee justified his words claiming that a nun in the pope's bedroom would have been inappropriate, creating fodder for a tabloid scandal. Regardless, his "white lie" fueled suspicions of a coverup of a papal murder.

A mass worth a murder?

Due to the complicated situation at the time, Pope John Paul I had to position himself between the Church's Traditionalist and progressive wings. Aided by the rumor mill of the internet, corners of the Catholic Traditionalist community claimed that the pope that allied with the Traditionalists over the progressives. Thus, the latter faction killed him to prevent a rollback of Vatican II and restoration of the Tridentine Mass. John Paul I allegedly telephoned Fr. Gommar de Pauw, the founder of New York's Catholic Traditionalist Movement. The pope shared his plan to restore the old mass and asked Fr. de Pauw to help. The Catholic Traditionalist Movement, however, denied the claims. Fr. de Pauw never received a call. But he did receive an official Vatican letter suggesting that he was in line for a Vatican job. The pope needed his help to bring "the Truth back to the Church."

The pope never got a chance to implement his agenda, so Fr. De Pauw's statements are open to interpretation. But they suggest that Fr. De Pauw and the pope wished to address the Church's issues (perhaps problems like liturgical abuse) within Vatican II's framework, not simply restore the old mass and act as if Vatican II had never happened. This attitude agreed with John Paul I's support for Vatican II (via National Catholic Reporter), suggesting that his goal was to reshape the Catholic Church to engage with the rapidly changing world without sacrificing its core teachings and traditions. The loyal Traditionalist Fr. de Pauw was a perfect candidate to ensure a smooth transition. Thus, if the pope was murdered, it was probably over something else.

A gorilla, a shark, and God's banker walk into a bar...

The above headline looks like a bad joke, but these are the three players at the center of the alleged murder plot. The Vatican Bank's establishment and Italy's generous concordat with the Vatican had allowed the papacy to enter the world of international finance tax-free, as noted in a 1982 New York Times article. In the 1970s, the bank's head was tough-talking Chicago native Archbishop Paul "the Gorilla" Marcinkus (pictured above), who earned his nickname from his size and strength. Marcinkus' philosophy, according to English crime writer David Yallop's book "In God's Name," was simple: "You can't run the Church on Hail Marys."

To help run the Vatican Bank's investments, Marcinkus contracted Milanese banker Roberto "God's Banker" Calvi, the chairman of Banco Ambrosiano, and Michele "the Shark" Sindona, a shady Sicilian financier whom the New York Times referred to as the man who "unloosed ... the largest bank collapse in U.S. history." The Vatican Bank scandal, which eventually came to light in 1982, was "mind-numbingly" complicated. But simply put, Calvi's Banco Ambrosiano, according to Crisis Magazine, laundered at least $1.3 million into shell companies that Marcinkus' Vatican Bank (Ambrosiano's majority shareholder) had helped set up. Sindona acted as their go-between and Marcinkus' financial advisor. When Banco Ambrosiano collapsed and the money was nowhere to be found, Marcinkus, according to the Washington Post, raided the Vatican's pension fund to replace the lost money. But his worldly dealings brought him into direct confrontation with John Paul I, a man who had grown up in poverty and felt that high finance was not the church's business.

The people's pope

Pope John Paul I was no fan of opulent living or high finance. Albino Luciani, as he was baptized, came from poverty. According to David Yallop's "In God's Name," Luciani was born in the remote Venetian mountain village of Canale, which greatly influenced his life and attitude towards his pastoral duties. Born the child of an itinerant laborer and housewife, Luciani lived in a converted barn with 10 siblings. He detested the opulent living of certain members of the papal Curia, who placed money and worldly status over God and the Church. This starkly contrasted with Luciani's austere seminary upbringing where even heat in winter was a luxury.

Unsurprisingly, Luciani clashed with Marcinkus and the Vatican Bank. According to the Italian newspaper La Stampa, Luciani had protested the 1973 sale of the controlling Vatican stake in the Venetian Banca Cattolica del Veneto to Roberto Calvi's Banco Ambrosiano. The Church-owned Venetian bank served the needs of Luciani's Venetian church and its parishioners with low-interest loans that maintained parishes and social services. When it was sold, these resources were lost. A furious Luciani allegedly confronted Marcinkus about his role in the sale, but he could do nothing. Marcinkus, on the other hand, denied there had ever been any problem. Upon becoming pope, according to Yallop (via Crisis Magazine), Luciani allegedly decided to take the Vatican Bank, Marcinkus, and his associates down. But his actions also threatened corrupt members of the Curia and the Italian elite, who were all connected through the shady Italian masonic lodge Propaganda Due.

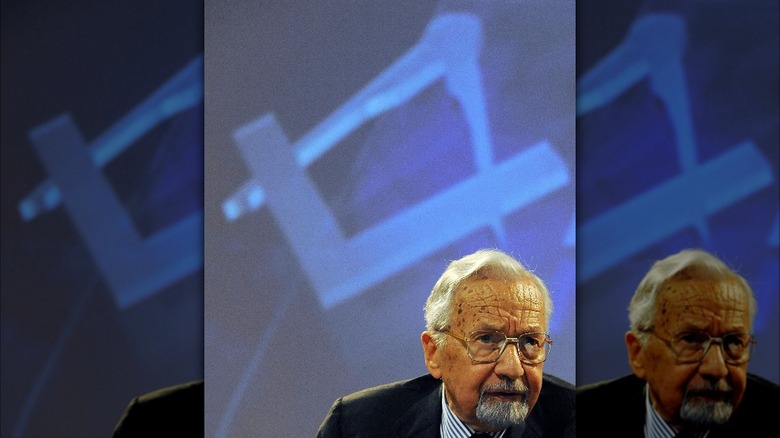

Enter the masons

Propaganda Due (aka P-2) was the brainchild of Italian financier and "always ... fascist" Licio Gelli (pictured above). This banned masonic lodge, as noted in Crisis Magazine, included top Italian generals, financiers, industrialists, and politicians, including Roberto Calvi and Michele Sindona. But most sensationally, it allegedly also counted high-ranking Vatican officials such as Paul Marcinkus and Vatican secretary of state Jean Villot among its ranks. This would have been an earth-shattering scandal. As the Catholic Encyclopedia notes, Catholics have been barred from freemasonry since 1738 due to its ties with the occult. Discovery of such membership (if true) would have resulted in the public humiliation of the Church and the punishment or expulsion of over 100 corrupt Vatican prelates that had broken their oaths to uphold church teachings.

According to David Yallop, when John Paul I decided to exorcise the demons of freemasonry and high finance from the Vatican, P-2 was able to throw the full weight of its political and religious connections against him. There are issues with this scenario, however. According to Crisis Magazine, when Italian police raided Gelli's home, they claimed that no members of the Vatican were on the P-2 membership list. But running a coverup likely would not have been difficult either, given the other illicit activites P-2 has been accused of. Regardless, full exposure of the scandal alone risked, at minimum, tarnishing the reputations of prelates and P-2 members alike. Thus, the pope had to die, and the well-connected P-2 was best positioned to organize the coup with help from another unexpected source: New York's Cosa Nostra, which has been implicated thanks to revelations from one of its former members.

Whacked?

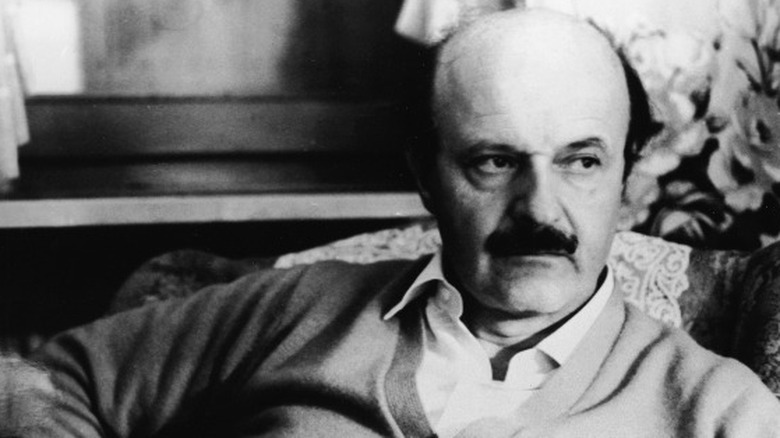

Although the Vatican has labelled David Yallop's investigation an "absurd fantasy," (via NY Times) the core of his analysis may be correct thanks to a bombshell claim out of New York. In 2019, former Colombo enforcer Anthony Raimondi (pictured above) claimed involvement in John Paul I's murder (via New York Post). He did not take part directly. As a nominal Catholic, he feared that personally killing the pope would be "a one-way ticket to hell." Instead, Raimondi's cousin, Paul Marcinkus, recruited him to spy on the pope, who had discovered a stock fraud involving the Vatican Bank. Marcinkus personally administered the lethal mix of cyanide and valium while the Vatican doctor covered it up, leaving the nuns to discover the body the next morning. Cyanide, according to Science Direct, can cause fingernail discoloration, which would explain Sr. Margherita Marin's observation of the dead pontiff's dark nails (via "The September Pope").

Raimondi's story, if true, would confirm many of Yallop's accusations against the church hierarchy, particularly claims that John Paul I was going to defrock "half the bishops and cardinals," placing them at the mercy of Italian and American justice. There are some discrepancies, though. Raimondi mentions a stock fraud instead of a money-laundering scam and completely omits any mention of the Propaganda Due lodge, although it is possible that he was not aware of the more secretive aspects of the plot. But his story does not end there. To wrap up any loose ends, he and the other conspirators ensured the John Paul I's successor would not dare touch the Vatican Bank, P-2, or any other corrupt elements of the Curia ever again.

Aftermath

After the Pope John Paul I died, he was embalmed and buried without an autopsy in accordance with Vatican protocol, leading to rampant media speculation (via NPR). The October conclave elected Polish cardinal Karol Wojtyla as Pope John Paul II. Paul Marcinkus escaped earthly punishment (if guilty), but his associates were less fortunate. According to Forbes, Roberto Calvi (pictured above) was found hanging from London's Blackfriar bridge (likely murdered) while his secretary Graziella Corrocher committed "suicide" by jumping from a window. According to the New York Times, Michele Sindona died of poisoning in Italian prison in 1986, while serving time for a raft of charges ranging from fraud to murder-for-hire.

Were the two fixers murdered to prevent exposure of their potential role in the pope's death? In Calvi's case, it is certainly possible. The timing of his death coincides with the unfolding of the Vatican Bank scandal in 1982. Sindona's death four years later, though, could have resulted from other issues. After all, both men had many powerful enemies outside the Vatican.

Now, there is still one more loose end. When John Paul II came to the papal throne, Marcinkus allegedly told gangster Anthony Raimondi (via New York Post) that the new pope could follow in his predecessor's footsteps. So they concocted a plot to kill him, forcing John Paul II to curb any suspicions he might have had. Raimondi and his Vatican friends went out to celebrate in Rome with a booze-and-women-fueled orgy. Is this just a tall tale, or had Marcinkus, Raimondi, and their associates pulled off the greatest murder conspiracy of the 20th century? You decide.