Nine Historical Events That Happened On New Years Eve

Celebrating the New Year is widely seen as an opportunity for a new beginning. New Year's resolutions, though the vast majority of them "fail," are a good example of this. Just like birthdays, New Years is a day when one period of time ends, and another begins. It is supposed to be auspicious, revolutionary, marked for relevance, and ... it usually isn't. We typically don't follow through on our promises to ourselves, and the vast majority of New Year's Eves end up with little to distinguish them from New Year's Days.

Sometimes though, the new year really is rung in with tremendous change. Every now and then, something happens that makes the coming year truly different than the outgoing one. From invasions to inventions to insurrections, occasionally New Year's Eve is indeed marked by the beginning, or end, of something that had, or will have, profound impacts upon the people (un)lucky enough to live through them.

The invasion of Gaul spelled the end of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was one of the history's largest and longest lasting civilizations. From humble beginnings as a bronze-age swamp in the center of the Italian peninsula, Rome grew into a sophisticated and powerful state, eventually covering territory on three continents. Rome's expansion was fueled in the same way all empires were: conquest and tribute. After over a century of warfare, Rome conquered and sold what was left of the Carthaginian Empire into slavery, claiming most of North Africa. A century later, Julius Caesar stomped through Western Europe, adding much of Britain, Spain, and most of France and Germany, subjugating millions of people, genociding entire tribes and ethnic groups, and selling them into slavery.

For centuries further, Rome's borders grew, until the society teetered under its own weight and corruption. Beset by political instability, economic chaos, and increasingly indefensible borders, in 395 A.D., the Roman empire was officially split into two (via the World History Encyclopedia). The Western Roman Empire, according to a 2021 paper in the Yale Historical Review, barely enjoyed 10 years of peace before "New Year's Eve, of either A.D. 405 or 406" when "a confederation of Vandals, Alans, and Sueves crossed the Rhine River and entered Roman Gaul." Having already lost Britain and Spain, the Roman military was still reeling from "two hard-fought civil wars," which meant that the well-armed group of 80,000 people crossing the Rhine River, "encountered no resistance," leading directly to the end of the Western Roman Empire.

One of the world's most powerful corporations started in 1600

The world was changing rapidly in 1600. For nearly 200 years, Europeans had been venturing further into the world, gobbling up territory in Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific. Britain was already playing the colonization game, too, but only recently, after defeating the Spanish Armada, had it become a serious naval power capable of confronting the trade monopoly held by the Spanish, Dutch, and Portuguese in the Asia-Pacific region.

To that end, explains ThoughtCo, a group of British businessmen asked Queen Elizabeth to charter a company that could establish British trading interests in Indonesia. The charter was authorized on December 31, 1600, and the British East India Company was born. The company floundered a bit, at first, being quickly booted out of Indonesia by the Dutch and Portuguese. They soon landed in India, however, and negotiated a deal with the ruling Mughal Empire to set up trading outposts.

As they were there for the specific purpose of competing with other colonial powers, the company charter allowed it to "wage war" to defend itself. It was a provision which quickly blossomed into an army, according to National Geographic, twice the size of Britain's actual army, which ruled India as a corporate colonial master for nearly a century. Finally, after over 250 years of illegally selling opium to China, selling slaves all over the world, and abusing Indians with famine and persecution, the Crown revoked its charter in 1874, dissolving the company.

It was the last day of the French revolutionary calendar

Centuries of absolute rule by the French monarchy had created a country wracked with inequality, exacerbated by decades of the king's reckless spending on foreign wars, imposition of unreasonably high taxes, and incompetent management of France's agriculture led to the infamously bloody French Revolution (via History). The government of the First Republic was intent on a complete reorganization of France and French society. The nobility was abolished, the metric system was adopted, voting was instituted, and even a new calendar was created.

The plan was to build an "rational" calendar, explains JSTOR Daily, "part of a project of rationalization and dechristianization" which didn't only change the names of the months but also added days to the week and nearly doubled the hour. The revolutionary calendar still had 12 months, but they were now three weeks of 10 days each. There were five or six days left over at the end of the year which were made public holidays, "in honor of the revolutionary working class." The days themselves were now 10 hours long, but each minute was 100 minutes, and each minute was 100 seconds.

Nobody was happy with this calendar — not the church and church-goers, who had to adjust their whole schedule of holy days, and not the watch and clock makers who had to reinvent their devices to accomodate these new temporal measurements. Just 12 years after the calendar was adopted, its last day of use came on December 31, 1805.

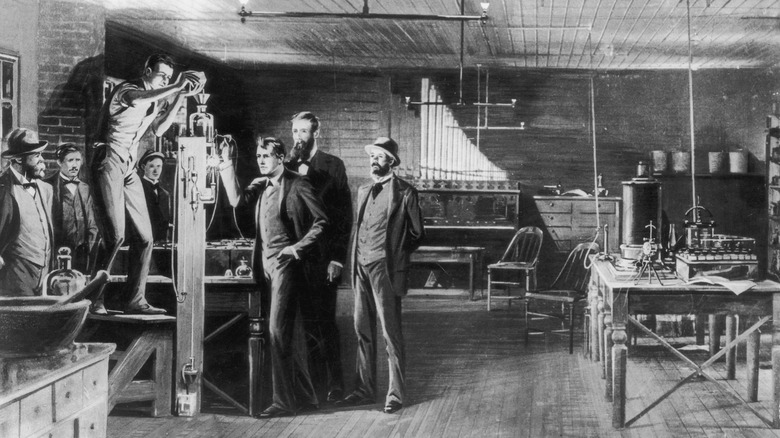

Edison demonstrates his light bulb for the first time in 1879

It took a long time for electricity to transition from an intellectual curiosity to a practical power source. Benjamin Franklin's possibly apocryphal electric kite experiment rested on centuries of prior discovery, dating all the way back to ancient Greece. Thales of Miletus, according to Phys.Org, was the first to discover static electricity, and some claim that a mysterious, ancient, Middle Eastern artifact called the "Baghdad Battery" was used for electroplating (via Smith College). Some 2,000 years later, per ThoughtCo, Englishman William Gilbert coined the word "electrica" in a treatise on magnetism, inspiring further research by a number of European inventors, which led to Franklin's famous discovery that lightning is made of electricity.

By the time that Thomas Edison set up his "Invention Factory" in Menlo Park, New York City, electric cars and even trains had already been invented, but it was many decades before a reliable battery and motor, so neither were very practical or useful. Thus electricity's most important function at that time was for the telegraph, the world's first telecommunications revolution. According to the Menlo Park Museum, the telegraph is what lit Edison's inventive imagination. He became a prolific inventor, if a downright shady businessman, changing the way we listen to the world with the phonograph in 1878. The next year, on New Year's Eve, Edison gave the first public demonstration of his lightbulb, and for the first time ever, a dark city street was brightened with electricity.

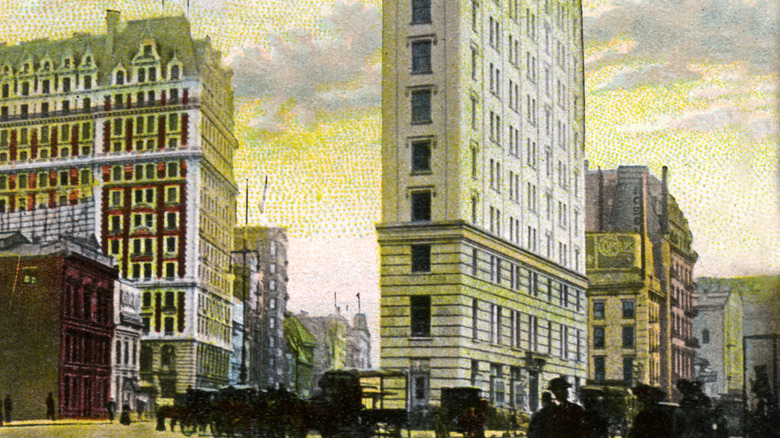

New York City's first Times Square New Year's Eve celebration was in 1904

The New Year's Eve celebration party in Times Square, New York City, is one of the world's biggest. According to BallDrop, over a million people brave the northeast winter cold to revel, and they are joined by a billion more people around the world watching on television. This is an admittedly strange addition to a list of events that happened on New Year's Eve, because when else would a New Year's Eve celebration be held? But there had to be a first time and, like so many firsts, there is a story.

The first Times Square celebration was held in 1904, a time of phenomenal change for the city. Amidst the ongoing electrification of the city, New York's first subways were opened, and the New York Times completed construction of its new headquarters, conveniently located at the intersection of four of the city's most important streets and near the new subway stations. The Times building was then the second-tallest in New York, and although, according to Mental Floss, nobody is quite sure why, the intersection was named Times Square. The Times' owner, says the official Times Square website, "spared no expense" at preparing a giant celebration as a publicity stunt for the New York Times' new location. Over 200,000 people attended, and the merrymaking could supposedly be heard 30 miles away.

Paul McCartney sued his fellow Beatles to end the band in 1970

The Beatles were arguably the most popular music group in history. Business Insider crunched the numbers, and the Fab Four have literally outsold every other band, ever. More than Michael Jackson, Eminem, and Taylor Swift, combined. According to CBS News, the mop-topped English boys sold over 1.6 billion singles and 177 million albums (over 600 million albums worldwide). They recorded more Billboard No. 1 singles than any other band, and their song "Yesterday" is the most covered single of any artist. The Beatles were the best selling rock band in 2020, 50 years after they broke up, and, says Forbes, they were the only band besides BTS to break a million units that year.

Their break-up has been the stuff of legendary speculation ever since and, while it seemed sudden to the rest of the world, it was a long time coming. Contrary to popular opinion, Yoko Ono was not the reason; the boys were fraught with money problems, and personality clashes were becoming concrete. The relationships between the bandmates had been disintegrating for years and, reported Rolling Stone, even though it was John Lennon who first vocalized his desire to leave the band, after "his caprices and rage had destroyed the band," it was Paul McCartney who pulled the plug. On December 31, 1970, McCartney officially sued for musical divorce from the biggest band in the world.

Russia's first democratically elected president resigned on live TV

The 20th century for Russia was bookended by chaos. Even before the communist 1917 revolution, per Britannica, Russia was a failing state; embroiled in economic stagnation, social collapse, and the effects of losing an expensive war. The end of the century was much the same, and at the helm of the floundering Russian nation was Boris Yeltsin.

Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev's efforts at reform led to a coup. As the US State Department Historian's office explains, Boris Yeltsin, then president of the Russian Soviet Republic, "advocated democratization and rapid economic reforms while the hard-line Communist elite wanted to thwart Gorbachev's reform agenda." Yeltsin's side prevailed, and soon the USSR melted away "relatively peaceful[ly]," leaving him president of the newly independent Russian republic.

Yeltsin was overwhelmed by the job. Russia's economy crumbled as Chechen separatists humiliated the military, and Yeltsin turned to drink. "Fairly early on," he wrote in his memoirs (per ABC), "I concluded that alcohol was the only means to quickly get rid of the stress ... I had to resign." In a shock to the still newly democratic Russia, President Yeltsin resigned during his traditional New Year's speech, leaving the newly-installed — and thus politically unknown — prime minister Vladimir Putin as president. "I want to ask you for forgiveness," Yeltsin said, "because many of our hopes have not come true." His resignation was less surprising to some, according to Russia Beyond, since Yeltsin was almost impeached three times.

America's most expensive highway project ever finally ends after 25 years

Boston is not known for being a driver-friendly city, or rather their drivers are not known for being friendly. Beantown's drivers consistently rank as the worst, or second worst, in the country, reported Boston Magazine. They've actually gotten worse during the pandemic, according to a 2021 poll of Bostonians themselves (via Boston Magazine). Massachusetts drivers as a whole, it turns out, have a bit of an unsavory reputation. "Why does everyone hate Massachusetts drivers?" asked automotive magazine MotorBiscuit, suggesting that maybe Massachusetts roads, known for being under constant construction, are to blame.

Boston's Big Dig is the shining example of constant construction. The idea of The Big Dig, a three-and-a-half mile long tunnel under the city, says Wired, was thought up in the 1970s: Planning started in the '80s, the construction began in the '90s, and the project wasn't declared complete until December 31, 2007. The Big Dig became the country's most expensive highway construction project in history. It went $12 billion over budget and was subject to multiple corruption investigations by state and federal agencies. According to NBC News, it even killed one driver during a partial collapse in 2006. To top it all off, a 2008 report by the Boston Globe found that The Big Dig actually ending up making traffic worse in some areas of town.

The last day of 2020 saw the authorization of the COVID-19 vaccinces

Amidst the hullabaloo about vaccine mandates, vaccine skepticism, and vaccine hesitancy for combating COVID-19, it's worth remembering that we went through an entire year of the pandemic without any vaccine at all. Between the debates on boosters, aside from comparisons between efficacy rates of different vaccine manufacturers, and beyond pontifications on vaccine diplomacy, it should be appreciated that we endured 12 months of a world with masks but no medicine.

Indeed, when then-president Donald Trump announced Operation Warp Speed, to fast-track research and development of a COVID-19 vaccine, it was met with repeated trepidation by some of the very scientists working on it. "I still think 12 to 18 months is an aggressive schedule," said the former head of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority to a Congressional committee last year (per ABC News), "and I think it's going to take longer than that to do so."

So when the World Health Organization (WHO) granted the first emergency use authorization to the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine on December 31, 2020, it paved the way for worldwide distribution and a path forward. "This is a very positive step towards ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines," said the WHO Assistant-Director General for Access to Medicines and Health Products in the WHO press release. Yale Medicine went on to report in late 2021, "Although each vaccine is unique, all of them offer strong protection against severe disease."