The Truth About The 1944 Prisoner Of War Olympics Of WWII

In 1944, almost 100 million soldiers from over 30 countries were deployed to fight in World War II, and by the end of this war nearly 75 million people would be dead (via World Population Review). The Olympics, the quadrennial celebration of international goodwill and friendly competition, scheduled for London, were canceled. There wasn't much goodwill to go around.

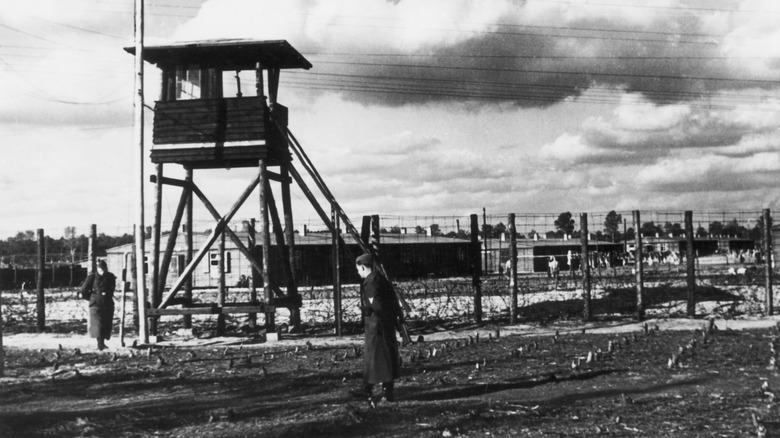

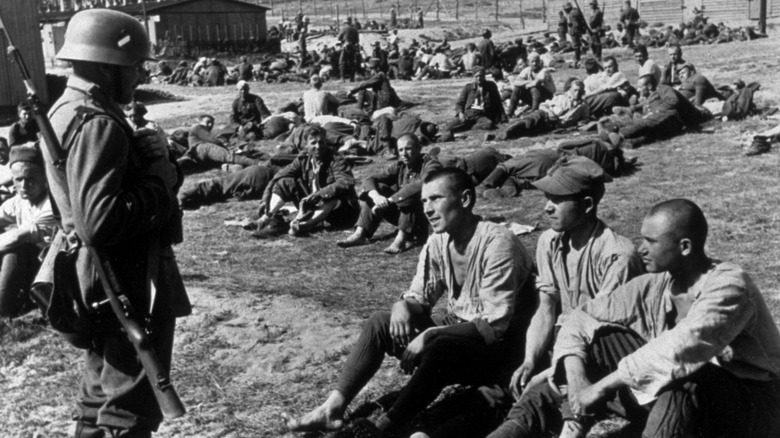

For those fighting in World War II, life was generally pretty awful. It had been that way for nearly five years. Poland, for example, was under German occupation, and nearly 18% of the country's population died (via History). It was a central axis for Axis crimes, and the Nazis killed over 90% of Jewish people in the country (possibly with the aid of the Polish government, and certainly without much resistance, according to History). About half a mile from Woldenberg, Brandenburg (currently known as Dobiegniew), the Germans had imprisoned 7,000 to 10,000 Polish people, mostly military officers, in camps for prisoners of war (via "Sports and Olympic Spirit in POW Camps" in the Olympex: The Olympic Expo). On January 1, 1945, these camps were evacuated and many of the inhabitants died when the Germans forced them to walk over 600 miles in so-called "death marches" (via Am-Pole Eagle).

One year before that, they found a way to celebrate their own humanity with a timeless ritual — a competitive sports celebration — and organized their own Olympic games, without money or press, from behind the barbed wire of a Nazi POW camp.

The 1944 Woldenberg Olympics

In a remarkable display of spirit, in May 1944, Polish prisoners at the Woldenberg POW camps organized their own "Camp Olympic Committee," and from July 30 to August 15, 1944, the prisoners competed in their own Olympic games (via Mental Floss). For roughly 22 days, the prisoners at Woldenberg competed in basketball, handball, volleyball, and chess. (Some of the participants' scores even came close to those of official sports competitions held in Poland in 1939, according to Olympex.) Prisoners crafted medals out of cartons and presented them to the competition winners in a ceremony, and they created their own Polish flags out of camp bed sheets (via Mental Floss and History). Colored scarves attached to the sheets imitated the logo of the International Olympics.

In a 2004 NBC documentary on the Woldenberg Olympics (via History), camp survivor Arkady Verjizinsky described the spirit of the games: "The excitement in the entire camp was unbelievable ... We were all there together ... and then the Olympic flag went up, the only one in the world, just in this spot."

Of the 7,000 people imprisoned at Oflag II-C Woldenberg (via History and Olympex), approximately 369 are said to have participated in the "Woldenberg Olympics." Another prisoner-of-war camp, Gross Born Oflag II-D (population approximately 3,000), held Olympic celebrations around the same time. Although Oflag II-C organized their celebration with the consent of their German captors, Oflag II-D held theirs in secret (via Olympex, Mental Floss).

'A symbol of struggle, though never blood'

Most of the people imprisoned at Woldenberg were Polish military officers, which may have earned them leniency from their German guards, as much as any POW camp's conditions can be said to be "lenient." The Woldenberg camps had their own postal service, musical celebrations, and even underground schools. Among the officers imprisoned were some former athletic instructors from the Central Institute of Warsaw and Poenon, and they quickly organized "military sports" within the camps (via Olympex and Am-Pole Eagle). Nonetheless, the conditions were far from rosy. The Woldenberg Olympics initially included boxing, but prisoners removed the sport from their self-composed roster when many participants, due to physical fragility and poor health, were injured or suffered broken bones (via Mental Floss).

Decades later, one of the former prisoners spoke about his memory of the 1944 Olympics (via How Stuff Works), particularly of the prisoners' self-made Olympic flag: "It seemed to us, who were removed from the war game that was being waged for life and death that it would be good if somebody, somewhere — even in the prison camp — remembered this banner, which has always been a symbol of struggle, though never stained with blood."