The Tragic History Of NYC's 'Death Avenue'

In 1906, the wealthy bureaucrats of the Upper East Side and Lower Manhattan sat in the statehouse debating the economic merits of an infrastructure project. Senator Henry Saxe argued that the 10th and 11th Avenue West Side train, dubbed "The Butcher," was living up to its name. He urged his colleagues that the train had to go, and such a matter of life and death no longer wait to be met with governance, as Indiana University's Joseph Varga recounts in his 2013 text "Hell, Death, and Urban Politics" (via Gotham Center).

In the previous decade alone, nearly 200 residents of the West Side — mostly children — had died from the steam engine as it plowed through the busy downtown district primarily populated by the urban poor. The High Line further reported that according to a 1908 report by the Bureau of Municipal Research, 436 people had been killed by the trains since 1852. Still, the senators demurred, citing issues such as the economic cost of rerouting the train and the cargo route's value to industry. As the senators were speaking, a messenger burst into the chambers: capitalism's locomotive of profitability and property rights had killed yet another boy, his body now gruesomely mangled across the 10th Avenue tracks.

Death Avenue

The train crossing the West Side of Lower Manhattan had earned 10th and 11th the name "Death Avenue" for the hundreds of fatalities that occurred there since the full-size steam engine was built in 1846. Scores of schoolchildren had been pummeled by the locomotive carrying goods from Albany to downtown, routed through a tenement district in the murkier, more smog-filled industrial neighborhoods of early 20th century cities that were home to the urban poor (via Atlas Obscura). The question, some argued, wasn't if the train was dangerous: everyone agreed that it was. The question was if the lives of the urban poor mattered as much as the economic convenience of the Upper East Side's wealthier men of commerce.

Until 1906, the answer had been no. But the preternaturally-timed death of this boy, although a not-uncommon occurrence on 10th and 11th, was enough to get the senators to budge, according to Varga (via Gotham Center). They voted in favor of Henry Saxe's bill: the city would come up with a new plan by 1908, or the city would condemn the property belonging to Central Hudson Railway Company where the notorious train tracks had been built, allowing them to seize it. Either way, the train had to go.

In Defense of the Urban Poor

The train did not go, and it soon became an epicenter of a vicious political battle about priorities in urban infrastructure when commercial interests conflicted with the rights of populations. The battle of civic influence, working-class outrage, and the timeless adversity between capitalist industry and an increasingly disenfranchised working class began to embody all the elements of early 20th-century struggles for Progressive reform.

The Industrial Revolution was far from a gleaming era of newfound wealth and capitalist luxury: for many, it meant smog-filled skies black with smoke and long days in factories as farm work got left behind. The post-Civil War urbanization of industry brought floods of people to the cities, and to say the cities hadn't preconfigured this population boom into their infrastructure plans would be an understatement (via Encyclopedia Britannica and World Bank Publications' 2009 report "Urbanization and Growth").

The Death Avenue train was built in 1846, according to High Line, to deliver goods from Albany to the factories on the West Side for use or further transport. The train, engineered by Central Hudson Railway Company, traversed up and down 10th and 11th Avenues, a steam engine with handbrakes operated by a single brakeman who sat atop the train. The train tracks were built directly through the town center with no fencing, barriers, or protective railing. Every day, scores of people crossed the tracks to get to their homes, schools, or workplaces.

The West Side Cowboy Compromise

The train had caused problems since its inception. In the words of a New York state senator, the train was "an evil which has already endured too long" by 1866 per Joseph Varga (via Gotham Center). In 1892, New York World said it was "a monster which has menaced ... [the people] night and day" (via The High Line).

In response to the outcry, the city had made one concession for public safety, albeit an odd one. In 1850, the city required so-called "West Side Cowboys," brightly-clad men on horseback, to ride before the train and alert pedestrians when it was near. The West Side Cowboys were romanticized in popular histories (via Untapped Cities), but these gaudy horsemen (often brought in from districts out of town) were unpopular among townspeople they were appointed to protect. The Cowboys were often accused of indifference or negligence at the scene of accidents and were mocked by the children who passed them on routes, who reportedly often pelted them with rocks. Regardless, the West Side Cowboys did little to stop the accidents.

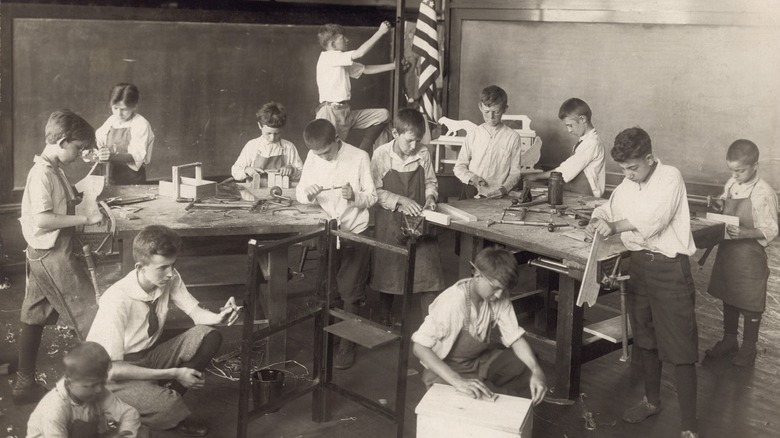

The Schoolboy Protests of 1908

In 1907, the battle over Death Avenue came to a head. On September 25, 1908, 7-year-old Seth Low Hascamp was playing "Follow My Leader" with his friends when he was hit and killed by the Death Avenue train. According to a 1908 New York Times article, the boy was "ground to death." It was unquestionably a tragedy that reignited long-simmering tensions between the city officials supporting the train and the residents who lived along its deadly path. When Seth's body was examined, the coroner seemed to take sides of his own: the Central Hudson Railway Company was not to blame. He said the 7-year-old boy was the one "at fault," solely responsible for his own gruesome death.

That was enough for the people of West Side. On the evening of October 24, 1908, over 500 of Seth Hascamp's friends and classmates marched in protest of the train, dubbed "The Butcher," draped in flags and singing somber hymns. Wealthy benefactors taking up the cause of improving the lives of the urban poor had become avid opponents of the Death Avenue train, and some inserted themselves into the environment of community outrage. Henry Schneider, Secretary of the Track Removal Association, and Michael J. McCarthy, an Independence League candidate for Senate, began to lead the seemingly-spontaneous marches, announcing they would march every Monday till election day, and wear "badges draped in mourning" for 30 days, according to the New York Times.

The Death of Death Avenue

The train kept moving, but the wheels of government churned slowly — the battle over the West Side train continued to play out in both the streets and the city statehouse. By the time the 1908 deadline for a new transit plan came and went, New York Central Railway was contesting the legality of the city's plan to seize its property — both opponents of the railway and advocates of the railway waged public relations campaigns to win the people to their side. The city received proposals from an array of corporate entities and civic organizations, each with their own ideas on what to build to replace the Death Avenue train, how to pay for it, and how to compensate the city for what they'd owe the railroad after, according to Varga (via Gotham Center).

The answer, it turned out, would be the High Line. In 1929, the government reached an agreement, and by 1934, the High Line replaced the Eleventh Avenue train — routed through warehouses and factories instead of busy streets. The last train ran along the "menacing" tracks in 1941. Now, all that remains of Death Avenue's specter and the lives it swallowed is a mid-sized plaque affixed to a brick building on 10th Avenue and 29th Street (via Atlas Obscura): "These old bricks and beams will never forget ... In memory of the hundreds of people killed by freight-lines on 10th Avenue between 1846 and 1941."