The Tragic Truth About The Triassic Mass Extinction

Over the Earth's long history, there have been five major extinction events. So far, anyway. Some are more famous than others — just about everyone has at least a rudimentary understanding of the KT extinction, which is the one where a large object from space collided with the Earth and caused the almost-immediate extinction of the dinosaurs. And it's worth noting that the planet is probably in the midst of the sixth major extinction event, caused by something even more destructive than an asteroid (that's us, y'all).

The five major extinction events happened at the boundaries between major geologic periods. The KT extinction, for example, happened between the Cretaceous and the Tertiary periods; lesser known is the Triassic-Jurassic extinction, which happened at the end of the Triassic and just before the era that was immortalized in a fake dinosaur theme park back in 1993 (the Jurassic).

Despite being lesser-known, the end-Triassic extinction was significant because it paved the way for dinosaurs to rule the Earth, so that they could then be taken out by an asteroid, thus paving the way for humans to rule the Earth. And in the end, everything else will be taken out by humans, thus paving the way for cockroaches to rule the Earth. It's a dystopian future, everyone.

Pangea did it

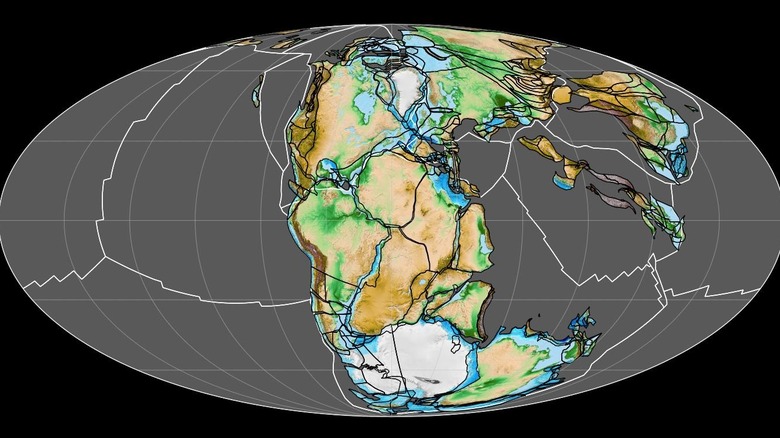

Two hundred million years ago, the map of the world looked pretty different than it does now. Today, the continents are separated by vast oceans; back then, they were all joined together in a kind of geologic kumbaya known as Pangea. The continents were all connected, so if prehistoric life forms had had the concept of asphalt, they could have road tripped from one end of the world to the other.

According to MIT News, Pangea started to break apart around the same time as the end-Triassic extinction. That on its own didn't contribute to the extinction — the animals living on one side of Pangea vs. the other were kind of just on a slow raft ride that would ultimately lead to diversification, not extinction. Rather, it was the geologic forces associated with the separation that made the conditions on Earth get a bit ugly.

The authors of a 2013 study published in the journal Science found evidence of volcanic activity dating to around 200 million years ago on the east coast of the United States and in Morocco, now-distant landmasses that were actually next-door neighbors before the supercontinent began to break apart (via Visual Capitalist). This part of the world — known as the central Atlantic magmatic province — was probably volcanically active for around 40,000 years, which coincides nicely with the time period of the end-Triassic extinction.

There were mega-monsoons

The end-Triassic extinction was complicated, and a lot of things happened over a long period of time that led to the eventual global mass extinction. The event was preceded by a number of local extinction events combined with a general decline of some animal groups. The first major contributor was the Carnian Pluvial Episode (CPE), which happened around 233 million years ago, a full 34 million years before the end-Triassic extinction and only about 19 million years or so after the Permian-Triassic extinction.

According to Modern Sciences, during the CPE, Pangea was a very hot and humid place that got a ton of rainfall, so much that scientists also call the CPE the "megamonsoon" period. Besides being very wet, it was also very dry — according to a study published in Science Advances, the period was characterized by dry spells, followed by wet spells, followed by dry spells.

This extreme climate, as it turns out, was good for dinosaurs, and bad for some of their cousins, especially the rhynchosaurs. Rhynchosaurs were herbivorous archosaurs sometimes described as "pig-like," which became abundant after the Permian-Triassic mass extinction (via Journal of the Geological Society) but died out around the time of the CPE. This may have cleared some space for herbivorous dinosaurs like the sauropods, which became one of the dominant groups after the end-Triassic extinction.

A meteor strike might have contributed

The asteroid-related KT extinction is so famous, it's kind of made us all associate "major extinction" with "major collision." But space debris didn't really play a role in most of the five major extinctions, at least not as far as science has been able to tell.

Some scientists, though, are toying with the idea that the end-Triassic extinction may have been at least partially influenced by an impactor (science's sort of generic name for an asteroid or comet that strikes the Earth).

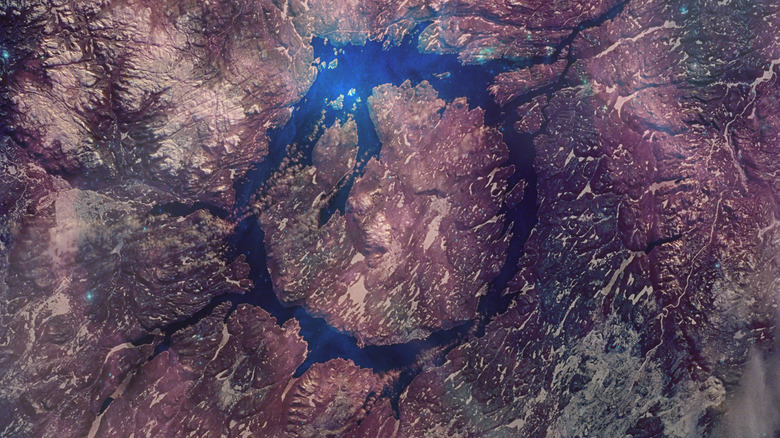

The Manicouagan crater is a 60-mile wide crater located in Quebec, Canada (via NASA). Scientists think the impact happened around 215.5 million years ago, which is technically 15 million years or so too soon to have been a major factor in the end-Triassic extinction event. According to a 2016 study published in Nature, though, the impact may have caused a large local extinction event driven by the decline of single-celled species at the bottom of the marine food chain. Though this wouldn't have been enough to cause the extinction event that began about 15 million years later, it may have at least contributed. Marine species like ammonites, for example, were already in decline as the end-Triassic extinction began, which may have been related to the major changes in the food chain that happened after the Manicouagan impact.

There was an initial drop in sea level

Today, scientists are concerned about rising sea levels. Even a small rise in sea level will be enough to wipe out entire coastlines, which as it happens is where people most like to live. But during the end-Triassic period, the extinction may have begun with a sea level drop, not the other way around.

According to a 2017 study published in Nature Communications, the sea level drop happened all over the world and may have been triggered by global cooling. This kind of cooling could have been triggered by early volcanic activity in the central Atlantic magmatic province. Sulfate aerosols released by magma reflect sunlight, which can actually have a cooling effect. They also change the composition of the clouds, which makes the clouds more reflective, too (via NASA).

According to a 2020 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the sea level drop would have created shallow, brackish areas within the marine ecosystem that encouraged the growth of microbial mats. This wasn't the major cause of the end-Triassic extinction, but it probably contributed to localized extinctions, which would have ultimately also contributed to the major extinction event that happened soon after.

Volcanic eruptions were the tipping point

The major part of the extinction event happened because of volcanoes. These weren't just Mount Saint Helens kinds of eruptions, either, they were the kinds of eruptions capable of literally breaking entire continents apart. As Pangea separated, volcanoes pumped massive amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. In fact, according to a study published in GSA Bulletin, there were at least two separate periods where carbon dioxide levels shot up, and those periods led to global temperature increases of as much as 16.2 degrees Fahrenheit.

Now, unless you've been living in an experimental climate-controlled bubble for the last couple of decades, you know what that means. Scientists have been warning us of the consequences of a mere 3.6 degree global temperature increase for decades (that's 2 degrees Celsius), so you can extrapolate from there about all the extreme climate events, extinctions, and general misery that followed this global temperature change. And by the way, according to Fortune, if we don't do something to change things here in the Anthropocene, we're currently on track for an 8.1 degree temperature increase by 2100. That means it's about to be at least half bad as it was during the end-Triassic extinction.

The ocean became more acidic

Scientists aren't really sure how bad it got for marine species during the end-Triassic extinction. According to a study published in Lethaia, the event coincided with the disappearance of certain ammonites, calcareous demosponges (sponge-like animals with calcareous skeletons), and some shelled animals like mollusks and brachiopods. What is clear is that the oceans became a lot less hospitable.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, large amounts of CO2 in the atmosphere translated to more acidic oceans. Up to 30% of atmospheric carbon dioxide eventually ends up in the ocean, and it doesn't just float around in the water, it triggers chemical reactions that increase the concentration of hydrogen ions in the water. That decreases the pH, or to put it in scarier terms, increases the acidity.

This is a big deal because increases in acidity can make it harder for animals like corals and clams to build their skeletons or shells, and those types of animals don't last long without their skeletons or shells. According to a study published in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, during the end-Triassic period even the deep ocean was much more acidic than normal, which would have contributed to species decline in the marine ecosystem.

About 76% of all species died out

Collectively, the extinction killed off around 76% of all ocean and terrestrial animals (via Britannica). It also resulted in the extinction of 20 percent of all taxonomic families. In case you need a taxonomy refresher (via Biology Dictionary), biologists categorize all living things by domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. Families are the more specific categories that fall under each major order. So for example, dogs are in the order Carnivora (large carnivores and omnivores) and in the family Canidae. This means the modern equivalent of the loss of an entire family would be if all the world's dogs, foxes, and wolves were to suddenly vanish. Twenty percent of the world's families would be one out of every five of these categories of animals.

Though we like to think of the KT extinction as the big one, scientists rank the KT extinction behind the end-Triassic extinction in terms of severity. Only the end-Permian extinction — which is colloquially known as the "Great Dying" and resulted in the demise of 95 percent of marine species and 70 percent of terrestrial species — is considered worse.

Goodbye, giant amphibians

You may not have even realized that there was ever such a thing as a "giant amphibian." The amphibians known today are frogs and newts, which don't tend to grow much larger than hand-sized except in a few uncommon cases (National Geographic says the modern "giant salamander" can grow to be more than five feet long). But for the most part, the giant amphibians died off during the end-Triassic extinction.

The Temnospondyls were big, like crocodile big. Cyclotosaurus, a Triassic species that lived in freshwater, could grow to be up to about 13 feet (via Palaeos). The Temnospondyls first appeared in the early Carboniferous (about 318 million years ago). They were among the most successful early four-legged animals, and were so diverse that there were even species that lived primarily on land, despite technically being amphibious.

According to a study published in the Journal of Iberian Geology, most of the Temnospondyls did not survive the end-Triassic extinction. Brachyopoids were the exception — this group of Temnospondyls shows up sporadically in the fossil record up until the Cretaceous, but by then they were more living relics than anything. Although to be fair, the largest amphibian ever known is a brachiopoid that lived during the Jurassic and was 23 feet long (via the Bulletin of the Geological Society of France) so you know, life finds a way.

The conodonts also disappeared

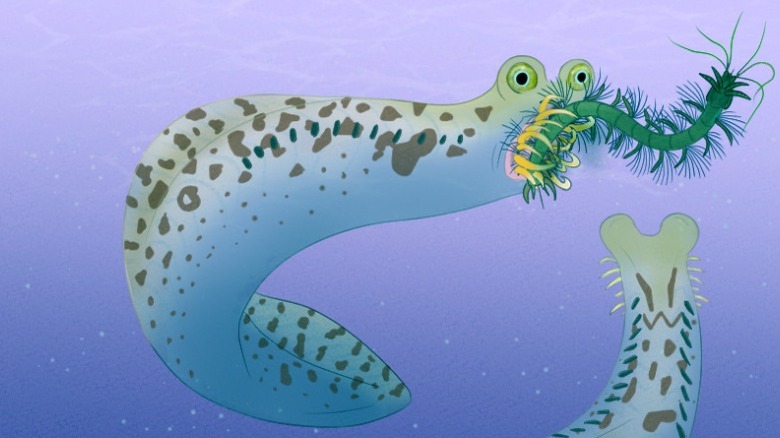

The conodonts were aquatic vertebrates that looked sort of like eels, sort of like worms, sort of like fish — in fact according to the Australia Museum, for a long time scientists didn't really know what they were, only that their fossils showed up in the record spanning the late Cambrian through the late Triassic.

If you encountered an outsized version of a conodont while out swimming, you might actually prefer to find some adjacent shark-infested waters to swim in, because they were jawless and therefore not really like anything you're used to seeing in the ocean. There were no outsized versions of them, though — the smallest was around 1/3rd of an inch and the largest known specimen was around 16 inches (via Australia: The Land Where Time Began).

The conodonts disappeared around the time of the end-Triassic extinction, but there's some disagreement as to whether it was the major extinction event that did them in or if they were sort of doomed to end on their own. According to a study published in Earth-Science Reviews, the conodonts were experiencing population declines throughout the late Triassic, which means it wasn't the warming climate or the acidic oceans that got them started down the road to extinction. Still, it's possible — maybe even probable — that the end-Triassic extinction was the tipping point for this already vulnerable animal.

Our ancestors survived

Way, way back in the fossil record, before mammals sprouted hair and took the first tentative steps towards world domination, there were the therapsids. This was a large order of reptiles that first appeared in the Permian, survived the Permian extinction, and hung out through the Triassic. According to Britannica, one line of therapsids was kind of special — the cynodonts appeared in the Carboniferous and eventually gave rise to the Pelycosauria, the earliest ancestors of mammals. Not all of the therapsids achieved such fame and fortune, though. According to Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, therapsids dominated during the early Triassic, but by the late Triassic they were already in decline. One likely reason is the diversification that happened after the end-Permian extinction — other animals filled in the empty niches, and therapsids kind of just faded into the background. Among the creatures that did not survive the end-Triassic extinction: the dicynodont therapsids (herbivorous animals with tusks).

In fact the only therapsids that made it to the Jurassic were the cynodonts. This group includes the first mammalian-type animals and the non-mammalian cynodonts (via Topics in Geobiology). Their survival marks a pretty important turning point — the first inklings of us.

Many of the dinosaurs' larger cousins vanished

Contrary to what a lot of people think, not all of the reptiles we associate with the Jurassic period were dinosaurs. Flying pterosaurs, for example, were on a separate evolutionary branch, and dinosaurs were grouped in with other Archosaurs ("ruling reptiles"), the group that also included crocodiles and birds (via Britannica). Distantly related to crocodiles was a group called the phytosaurs. They were armored, carnivorous, and semi-aquatic, much like the crocodiles of today.

According to National Geographic, the phytosaurs were just some of the many large archosaurs that dominated during the late Triassic. Aetosaurs, which were related to phytosaurs but have so far only been known to have lived during the late Triassic (via the University of California Museum of Paleontology) and the rauisuchians, which were also related to crocodiles but looked more like dinosaurs (via National Geogrphic) were some of the other major predators, and they were much bigger than the dinosaurs that lived during that time. In fact during the late Triassic, early dinosaurs were kind of in the same spot as the mammals were just before the KT extinction event — they weren't big enough to be of much consequence, but they were tough enough to survive what was coming.

Plants had their ups and downs

Extinction can be selective, though science doesn't always understand why. While there's evidence that large numbers of plant species went extinct at the end of the Permian (up to 90%, via University of Kansas), scientists aren't really sure how terrestrial plants were affected by the end-Triassic extinction event. The authors of a study published in Global and Planetary Change looked at the diversity of ferns in the Sichuan Basin of South China at the end of the Triassic and found that ferns in particular were quite good at adapting to new conditions — as the conditions in the area became dryer, species that were drought-tolerant moved in to fill the niche.

Another study, though (via Frontiers in Earth Science) found that plants in coastal areas didn't fare as well. Rising temperatures combined with a rising sea destroyed coastal habitats and drove some trees and shrubs to extinction, while others became exceedingly rare. When these plants disappeared, the sorts of species that thrive in disturbed areas moved in, but that didn't last long either. Soil erosion and increasing wildfire activity soon made it impossible for those species to survive, too, which led to a sort of second extinction crisis. Ultimately, plants rebounded, but the plant communities of the early Jurassic looked very different from the ones that existed in the late Triassic.

Pterosaurs survived, too

Pterosaurs were among the species that were wiped out during the KT extinction event, but they survived the end-Triassic event. Scientists can really only guess as to the reason. The authors of a study published in Nature, Ecology & Evolution think it was because pterosaurs were just really good at adapting to different climates. In 2018, a pterosaur fossil was discovered in north-eastern Utah, an area that was very hot and dry during the late Triassic. But pterosaurs have also been found in coastal environments, which says something about how hardy they were — evidently they were just as happy in the desert as they were at the beach.

Researchers presenting to the EGU General Assembly in 2012 were a little more specific about how pterosaurs might have survived the extinction. While the volcanic events that marked the end-Triassic extinction did cause an increase in global temperatures, they may have also produced short periods of cooling as they released sulphur aerosols into the atmosphere. The bodies of pterosaurs (and dinosaurs, too) had natural insulation, which may have protected them during the cooling events while similar not-so-insulated species perished.

And then dinosaurs rose

Dinosaurs emerged during the middle Triassic, rose to prominence during the Jurassic and dominated throughout most of the Cretaceous. So they were eventually flattened by an asteroid — at least they could look back and say they had a good, long run.

The dinosaurs not only survived the end-Triassic extinction event, it was actually good for them. They lost a lot of their most important competitors, including the phytosaurs and their cousins, and when those niches opened up it paved the way for dinosaurs to become bigger, faster, and meaner. According to the Conversation, the dinosaurs that survived the extinction event were small, and may have had other biological features that helped ensure their survival — a fast growth rate, for example, or very efficient lungs. More importantly, though, they were poised to jump into the empty spaces left by larger reptiles, which allowed them to undergo dramatic changes in size and diversity. And who knows what would have happened if the KT impactor had missed the Earth by a couple of thousand miles — maybe T-rexes would have evolved into dinosaur people, and they'd be the ones pondering the coming extinction event. Or maybe not. Those tiny hands would have been pretty useless on a keyboard.